8 Times Dunkirk Got History All Wrong

Christopher Nolan's Dunkirk takes the high bar set for war films and Nolanizes it, giving us lavish sets, explosive action, and disconcertingly fluid timelines. Visually, it's a masterpiece, and one of the most unique war films to date. Based on the real-life Battle of Dunkirk, the movie follows the evacuation of 400,000 soldiers from a French beach in the opening stages of World War II. For the most part, the movie sticks religiously to the facts, taking inspiration from actual war photos to frame the action. Even that weird-looking sailboat at the end was there.

But it doesn't get everything right. Here are all the ways Dunkirk got history wrong.

Nazi nose cones

Christopher Nolan was actually pretty candid about this historical discrepancy. In the movie, the German planes that Tom Hardy's character fights have their nose cones painted yellow. That's something the Germans actually did in the war — just not until about a month after Dunkirk, according to Nolan. The reason he decided to adopt the color scheme for the planes in the movie was a simple matter of identity. During the dogfights, the yellow identifies the planes as German at a glance, making it easier for audiences to keep up with the action without trying to figure out who was who the whole time. Does it work? Definitely.

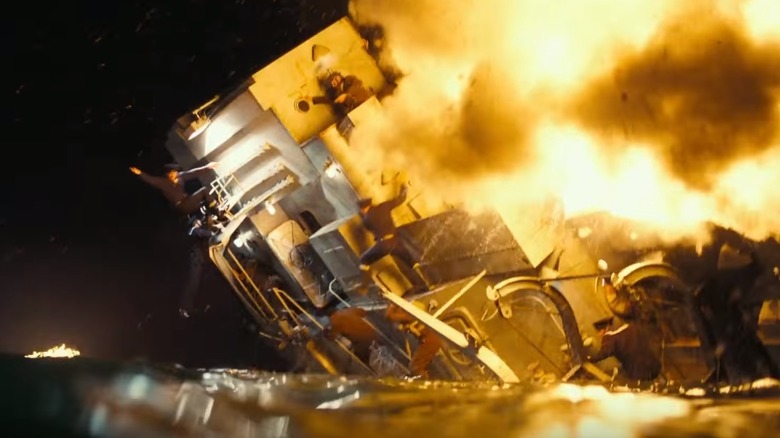

French destroyer

Nolan also came clean about another historical alteration he had to make for the sake of the film — namely, filming on a French destroyer instead of a British destroyer. See the differences between the two? Yeah, neither did most viewers. Besides being a detail that only a hardcore history buff would ever notice, the important takeaway here is that Christopher Nolan filmed on a real destroyer floating in real water instead of falling back on CGI for the entire ship. We'll happily take an extra smokestack over another Battleship, thank you.

Farrier's fuel tank

When we first meet Tom Hardy's character Farrier in the film, he's already in the air, and the big words on the screen handily announce that his story lasts an hour. In that hour, we see him engage in several dogfights, pull crazy stunts, and mercilessly hit the throttle, all while chalking his remaining fuel on his instrument panel. It's very, very intense. Butt-clenchingly intense. We're right there in the cockpit with him, feeling the pressure as that fuel starts to run out. But...you know where we're going with this. He should have had plenty of time to do his thing.

The main fighter used by the Royal Air Force at Dunkirk was the Supermarine Spitfire Mk1. That's what RAF pilots flew at Dunkirk, and what Farrier flies in the film. They were fast, agile planes with a fuel tank that could hold 85 gallons, giving them a 395-mile combat range. Now, here's a different number: 55 miles. That was the distance ships had to travel across the English Channel between England and Dunkirk. By air, it's even shorter. In the hour showing Farrier's story arc, he starts at 50 gallons in the tank and has to pop his reserve tank by the time he reaches Dunkirk.

Even accounting for the dogfights and switchbacks to chase the bomber going after the British destroyer, that hour's flight time should have gotten him to Dunkirk and back across the channel before teatime, considering the fact that Spitfires could fly upwards of 360 mph. Oh, and unless they were refitted for reconnaissance missions, there was no reserve tank on the Spitfire Mk1. But hey, that powerless glide he did at the end was totally legit.

Civilian volunteers

We saw in the movie how Mark Rylance's character, Mr. Dawson, risks life and limb to pilot his small sailing yacht across the Channel and into Dunkirk. The guy's a hero, and there's a true-blue historical basis for his exploits. In real life, a fleet of about 700 private craft assisted in the evacuation effort. They were called the Little Ships of Dunkirk, and yeah, they were pretty awesome. And it's true that some boat owners took up the call and sailed their own ships for the evacuation. Just...not very many. According to the Association of Dunkirk Little Ships, the vast majority of those boats were requisitioned by the British government (many of them without the owners' permission), at which point Naval officers were assigned to sail them to Dunkirk.

So maybe the movie focused on one of those precious few civilians who bravely chose to take their own boat into the warzone. That's totally plausible...until the end, that is, when we see all those civilian captains who jumped up to do their part in the evacuation just like Mark Rylance. In real life, 99 out of 100 of those guys would have been in uniform, doing their jobs as part of the Navy. And speaking of the Little Ships...

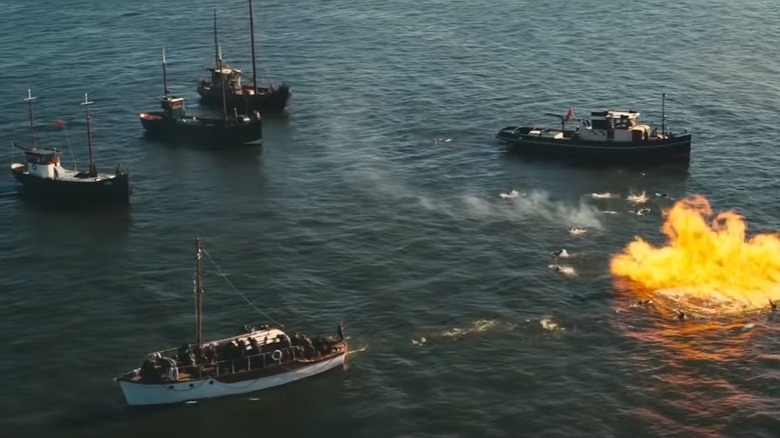

The cavalry arrives

It makes a grand, foot-stomping climax when the flotilla of Little Ships sails up to the beach at Dunkirk. It's an awesome cavalry-save-the-day moment straight out of a Western. And true to that metaphor, it was purely silver-screen suspense. Operation Dynamo lasted from May 26 to June 4, an unholy 10 days of terror for the soldiers trapped on the beach and for the ships trying to get them off the beach. Both the Little Ships and the British Navy worked tirelessly over those 12 days, making trip after trip back and forth between Dunkirk and England.

Dunkirk doesn't give exact dates, but it's a fairly safe guess that the finale of the movie – when all the timelines come together – is May 2. That's when Kenneth Branagh's Commander Bolton says that they'd rescued almost 300,000 soldiers, and historical records indicate that May 3 was when the total number of rescued men surpassed 300,000. But by that point, the Little Ships would have been shuttling back and forth for more than a week, so the sight of them wouldn't have been anything out of the ordinary. They played an important role in the evacuation, no doubt about that. But the real story of Dunkirk was one of slow survival, not sudden rescue.

Saving the day

Okay, one more thing about the Little Ships. Look, those ships were amazing. They weren't even outfitted for war, and they still braved aerial bombings and U-boats and mines to help out at Dunkirk. But while they definitely helped, their contribution has gotten a little inflated in the years since 1940.

Remember, there was no heroic moment where the ships arrived to save the day, the music didn't swell, the soldiers didn't cheer. Okay, well, they might have. It'd be hard not to cheer at any boat floating in to get you out of hell. But still, looking at the numbers, the Little Ships didn't "save the day," by any means. Out of the 338,000 men rescued, 239,000 were taken off the mole (that pier thing) by Navy ships. Less than 100,000 were picked up off the beaches, and many of those were ferried out to larger ships by the ships' own light craft. Only 6,000 soldiers made the trip across the Channel in one of the Little Ships. Their contribution to the evacuation effort can't be understated, of course. But it can be overstated. And it often has been. Unlike Die Hard, there's no single hero in this story.

The French connection

At one point in the movie, we see French soldiers clamoring to get onto the East mole that leads to the evacuation ships, only to get turned away by a British officer who tells them that the British ships are for the British soldiers, and that's final. That's about the last we hear from the French until the end, when Commander Bolton says that he'll stay behind to help evacuate the French.

Except...that's not how it went down. Of the 338,000 soldiers taken off the beach, 123,000 were French soldiers. That's more than a third of everyone who got rescued. As for the French soldiers who didn't make it off, they weren't fighting to get on an evac boat. No, they were back in the actual town of Dunkirk, holding back the Germans while the evacuation took place. Estimates put French casualties at Dunkirk between 50,000 and 90,000, and thousands more were taken captive because they took a stand and dug in to defend the other soldiers on the beach.

Ruins of Dunkirk

The majority of Christopher Nolan's Dunkirk takes place on the beach, at sea, and in the air, the trifecta of Nolan-Time that makes up the narrative of the film. However, we do get a few glimpses of the town itself — Dunkirk is a town, not just a beach — mostly in the beginning, but also near the end as Tom Hardy's Farrier glides over the beach. What we see is apocalyptic vacancy, but no real destruction. Buildings are standing, but empty. There are pleasant-looking summer homes peeking over the dunes. Except for the pile of sandbags in one scene, it's like everybody just left for lunch at the exact same time.

What should we be seeing? Utter ruin. Leningrad-scale devastation. Rubble in the streets, at the least. Between the Luftwaffe bombers and shelling from the German approach from the East, Dunkirk was brought to its knees during the evacuation. Christopher Nolan actually filmed Dunkirk in the town of Dunkirk, which lends historical presence to the film, but it doesn't reach far enough to relate the true gravity of the situation. Thousands of everyday lives ground to a halt the minute Allied troops retreated to Dunkirk, and it took years after the war to rebuild those lives to something resembling normalcy.