Wes Craven's Best Movies According To Rotten Tomatoes

Some filmmaking legacies are bound to live on. Alfred Hitchcock is still considered the absolute master of suspense. Akira Kurosawa's impact stretches further than he could have ever guessed. Films last not only because of how the public remembers them, but also because filmmakers are continually inspired by them. They study classics and go on to produce their own films, continuing the legacy of a great work of art.

With successes like "A Nightmare on Elm Street" and "Scream," it's clear that the work of Wes Craven is also destined to live on. Yes, we will likely get new incarnations of Freddy Krueger and various Ghostface killers for decades to come, but it's the impact this craftsman had on the current flock of directors that ensures he will not be forgotten. With that in mind, we decided to take a look at what Rotten Tomatoes consider to be Craven's best movies and talk about how each fits into his impressive career.

Scream 4

Some 11 years after the conclusion of the "Scream" trilogy, a new Ghostface emerged in the town of Woodsboro, hoping to open old wounds wider than ever. Craven's fourth "Scream" film could have easily been a cynical cash-grab. The story was over. Sidney Prescott had accepted and overcame her trauma following the events of "Scream 3." There was really no reason to produce a fourth film.

Still, this unexpected installment took things a step further than its immediate predecessor. While that film lampooned Hollywood and celebrities to a ludicrous degree, resulting in a slightly more lighthearted "Scream" film, this fourth chapter took the concept of celebrity a bit more seriously. Now that Sidney has decided to tell her own story, people aren't sure what to make of her. Is she a brave survivor channeling her terrifying experiences into something positive, or is she just an attention-seeking hack exploiting the pain of others for her own financial gain?

While the answer is obvious to us, a few of the characters around her aren't so sure. It's a scathing look at how society worships and loathes survivors of violence, and it raises deeply disturbing questions about craving notoriety with a final reveal that is more chilling than anything that came before.

The People Under The Stairs

A major motif running through the majority of Craven's work is the line between a civilized person and a monster. While it's even present way back in his first film, "The Last House on the Left," it's never been more upfront and obvious as it was in "The People Under the Stairs." If you're looking for it in his earlier work, you'll primarily see it as subtext. In this 1991 film, however, it is just plain text.

Really, the film is a Reagan-era fable about greed. It's about a young kid named Fool, living in a rough part of the city and helping his older sister's boyfriend steal from the vile landlords who are evicting them from their homes. These nameless slumlords — credited as Man and Woman, but calling themselves Daddy and Mommy — appear as well-to-do American citizens trying to make a living, when they're really truly twisted and evil human beings literally feeding off their underprivileged tenants.

Despite Man being one of Craven's more sadistic, depraved, and truly bizarre villains, and the overall bleak and satirical tone, the movie has one of Craven's more uplifting and hopeful endings, worthy of a traditional fairy tale.

The Last House on the Left

There's no way around it. "The Last House on the Left" is a very rough film. From its production value and odd structure to its obviously raw and traumatic subject matter, We Craven's very first film is not an easy watch. It is every bit as shocking, gut-wrenching, and twisted as its reputation suggests. While the 2009 remake was certainly tense, it pales in comparison to the unflinching brutality of this 1972 shocker.

What's interesting in a historical context, however, is just how perfectly this exploitation movie inspired by Ingmar Bergman's "The Virgin Spring" sets up the rest of Craven's career. Not only is it a crystal clear example of Craven's habit of depicting murder as something to be feared and not celebrated, but the film's final image also says everything you need to know about what his career would become.

After committing all kinds of horrible and grotesque acts against two young women in the woods, a gang of murderers seeks shelter in the home of one of their victims. Realizing that the people staying with them murdered their daughter Mari, these respectable people turn into merciless monsters of vengeance. While the audience wants to celebrate Mari's parents getting justice, the film ends on a still of the couple, bloody and confused. The message is clear: every human being is capable of horrible acts and violence solves nothing.

Mari's killers are dead, but so is she. Killing them in response made no difference.

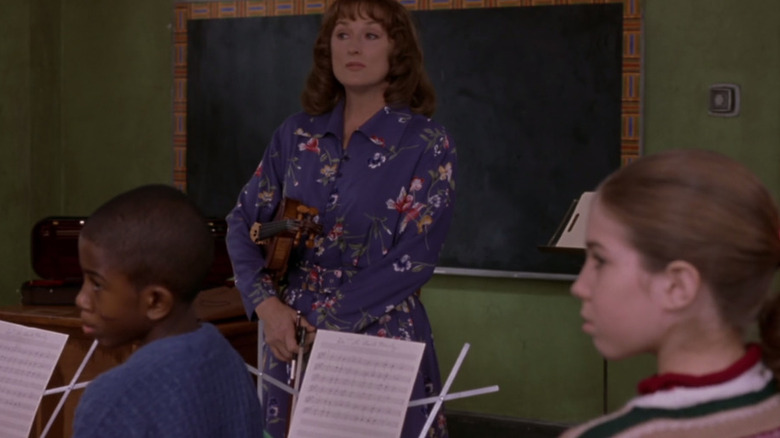

Music of the Heart

When looking at Wes Craven's filmography, 1999's "Music of the Heart" sticks out like a sore thumb. Did the master of horror really make this sentimental Meryl Streep drama about a white woman teaching violin to kids in Harlem? He did. Not only that, it actually looks and operates like a standard Wes Craven movie — if you look past the lack of violence.

Visually, if you were to watch this film alongside earlier works in urban settings like 'The People Under the Stairs" or "Vampire in Brooklyn," it would fit right in nicely. Craven has a penchant for filming real locations like a documentary, giving even his more fantastical films a grounding in reality. Thematically, it also explores Craven's interest in class, even if it doesn't look into it as deeply as some of his other films.

Based on the true story of violinist Roberta Guaspari, "Music of the Heart" is all about societal divisions. Learning to play classical music isn't considered essential in these Harlem schools. The kids don't see the point and neither do the administrators. Still, Guaspari is determined to use her passion to make a living for herself and open up a whole new world to some kids who don't necessarily believe in themselves.

The Hills Have Eyes

In 1977's "The Hills Have Eyes," Wes Craven takes the idea of good people capable of terrible acts one step further by making the obvious antagonists of the film beastlike. The 2006 remake turned the cannibalistic family of desert dwellers into mutants, but the original kept their origins a little vaguer. Unlike Krug and company in "The Last House on the Left," this vicious family dresses like characters out of a post-apocalyptic film and snarl like animals.

By making the killers in the film dress in this fashion, it instantly makes them out to be "the other." These aren't real people like you and me, are they? They're inhuman monsters who deserve to be slaughtered, right? Well, they have a family structure too. They call each other by their names and are expected to listen to their parents, just like the characters we feel like we should be rooting for.

If nothing else, "The Hills Have Eyes" begs the audience to engage in a little self-reflection. Sure, you watch the movie to experience fear in a controlled environment, but you're walking away with a little more than you bargained for because now you have to wonder, "Is my family really all that different than Papa Jupiter and his tribe? If we were desperate enough, could we resort to that kind of inhumanity?" It's a question Craven would revisit time and again.

The Serpent and the Rainbow

On a pure filmmaking level, 1988's "The Serpent and the Rainbow" is one of Wes Craven's most ambitious and accomplished films. It has a scope and depth to the cinematography that is rarely seen in his other work. Certain scenes with his trademark documentary style make the streets of Haiti come alive in a very palpable way, while the nightmare sequences rival anything he accomplished in "A Nightmare on Elm Street."

Where the film falters is the main character's dramatic need. We know Bill Pullman's character wants to get the zombie powder to benefit mankind, but why is he so driven to succeed in the face of true horror? Although the film was inspired by a true story, there are clearly enough fictional elements to justify contriving a personal journey for the character. He is up against some seriously bad people and dealing with a power he has no way of understanding, yet still he continues to put his sanity and life at risk. Yes, it's admirable to want to help the world, but what's his personal justification?

That being said, it's easy to see why this ranks among Craven's best works. A lot of the strong violence he's known for takes a backseat for a more psychological story about control, allowing audiences to appreciate the subtext a little more than they would have otherwise.

Swamp Thing

Seven years before Tim Burton's "Batman" in 1989, "Swamp Thing" was an attempt to bring one of the darker DC characters to the screen. It's an oddly timed adaptation since there weren't a lot of comic book movies trying to honor their source material at the time, and Alan Moore hadn't yet given us his iconic take on the character. Also, Craven hadn't quite reached the commercial heights he would with "A Nightmare on Elm Street," so the budget isn't quite there to adequately bring this complicated character to life.

Still, Craven's enthusiasm for the work is clear. Again, his documentarian style is a major attribute. The swamp itself feels vast and dangerous while also a tad serene. Dr. Holland's lab is refreshingly drab, giving it a reality lacking in many comic book movies. There's also a strong dichotomy between genuine scientific breakthroughs for the good of mankind and human greed.

While it isn't a spectacular film and the passage of time has done it few favors, it is a valiant attempt at treating a borderline goofy character seriously and a strong effort by Craven to prove that he's more than just an exploitation director.

Scream

For most scary movies, all you need to hook an audience is a fresh take. The original "Scream" is probably best remembered for being a self-aware slasher film that toyed with audience expectations. The driving force of this 1996 movie is a killer with a passion for scary movies hunting high school kids. That would be enough to make any slasher movie a hit, but "Scream" bumps everything to the next level by making us care about these potential victims.

Sidney Prescott isn't your typical final girl. Not only can she fight back, but she is a wounded character who hasn't done the work she needs to heal. Following the rape and murder of her mother, Sidney is on autopilot. She tries to appear adjusted and normal, but she's full of fear and torment. Only through a series of grisly murders is she forced to accept her trauma, embrace it, and move forward. That, and a host of entertaining characters, is what keeps this film fresh in the minds of audiences.

Sidney's trauma also fits right in with the rest of Wes Craven's filmography. As we've already discussed, and will continue to discuss, the family unit is a major element of Craven's work. Specifically, he often depicts how families break down in the midst of a crisis. In the case of Sidney Prescott, it's dealing with the truth about the woman she thought was a saint, but who turned out to be more complicated than she'd ever expected.

Red Eye

Wes Craven has always been pretty good at creating tension. In the early days, it was the notion that at any moment we could see something so shocking that the image burns itself in the back of our brains. As he matured, the tension came from the characters. "Red Eye" is, without a doubt, his most tense film. There are great moments of tension in most of his work, but nothing as tightly wound and set to snap as this 2005 effort.

This is another example of a Craven film that sidelines extreme violence. Instead, the entire focus is on Rachel McAdams and Cillian Murphy on a plane together. Everything comes down to the claustrophobic set and the heated performances of these two actors at the top of their game. Murphy is so approachable and charming, you can't blame McAdams for trusting him. In return, she's so great at playing someone who realizes the danger she's in but is perfectly capable of keeping herself together.

Given the simplicity of its plot, excellent performances, and lack of strong violence, it's obvious why critics tend to prefer "Red Eye" to Craven's more extreme work.

Wes Craven's New Nightmare

Before "Scream," Wes Craven ventured into the waters of metatextuality with the seventh installment of the "Nightmare on Elm Street" franchise. After years of inundating the world with Freddy Krueger everything, New Line Cinema killed the character. To bring him back, the man who created him returned. While each sequel to his 1984 classic had their own charms and merits, this 1994 film decided to step out of that reality and tell us about the people who made those movies.

Instead of following Nancy (who died in "A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: The Dream Warriors"), we meet Heather Langenkamp, the actress who played her. She's now a married woman with a husband who works in the special effects industry, a child and a stalker. She's not sure about making horror movies anymore, and she's been having nightmares about Freddy Krueger. This time, though, Freddy's bigger, darker, and meaner.

This is just a great film all around, but the real gold can be found in its message. This entire film is about why horror movies are important. In simple terms, the movie tells us that horror movies are therapeutic ways of exorcising our demons, not creating new ones.

Scream 2

The "Scream" films have a tendency to surpass the audience's expectations. The first film was about knowing what they expect and giving them something else. With the 1997 sequel, it was about taking everything that worked about its predecessor and pushing those elements further. This could have been a film about another killer slaughtering another group of teenagers, as is the tradition with slasher sequels. Instead, the film stuck with its protagonist, opened and deepened her character, while taking the metatextual aspects to the extreme.

The events of the first "Scream" have been turned into a book written by Gale Weathers and adapted into a film directed by Robert Rodriguez called "Stab." This movie-within-the-movie element carries on in each sequel after this. To honor the previous film by continuing to explore the characters and fictionalize those events was practically unheard of at the time and serves the film well.

It also features two of the most effective and shocking deaths in Craven's filmography. One is shocking because we love the character. The other affects us because it is about us. An entire audience watches as a woman is murdered in front of them and they're too caught up in the fiction to recognize the reality. It's a harrowing and humbling moment.

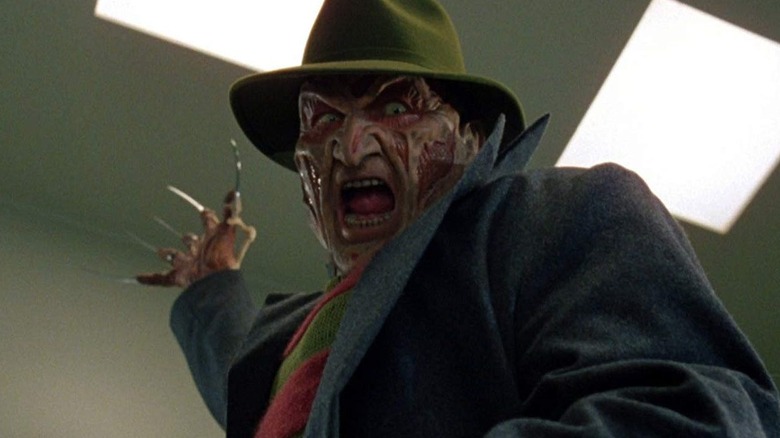

A Nightmare on Elm Street

Of course "A Nightmare on Elm Street" is Wes Craven's best film, according to Rotten Tomatoes. It is a masterpiece. To anyone who has formed their opinion of the entire "Nightmare" franchise based solely on some of the goofier sequels, go back and watch the original again. You'll bump up against a lot of the special effects, but the atmosphere will suck you in.

Everything Craven does well is on display here. The world feels real and grounded, perfectly setting up the surrealism of the nightmare sequences. Freddy Krueger is truly menacing, embodying our subconscious fears with sick pleasure. Nancy's family is crumbling under the weight of their decision to seek vigilante justice. Seemingly normal citizens harbor a horrible secret. Much of the violence is just as powerful as anything in "The Last House on the Left" or "The Hills Have Eyes." The sense of humor is pitch black. Finally, the message about violence never solving anything is the heart of the film.

After a technicality prevents a local child killer from going to prison, neighborhood parents band together to burn the man to death. While this may feel like a justified act, it comes back to hurt them in ways that are impossible to imagine. There is so much to dissect and ruminate over that it's no wonder why viewers have been coming back to Elm Street for nearly four decades.