The Wildest True Stories From '70s And '80s Martial Arts Films

Martial arts films in the 1970s and 1980s yielded a wealth of memorable performers and titles: iconic artists like Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan; hard-hitting, blood-soaked movie catalogs of the legendary Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest Studios; the guilty pleasures of Chuck Norris, Jean-Claude Van Damme; direct-to-video mayhem and so much more.

The 2021 book "These Fists Break Bricks: How Kung Fu Movies Swept America and Changed the World" details not only the incredible stories behind martial arts films and performers in the down-and-dirty '70s and '80s, but also the popularity and influence of these films on audiences in the United States and across the globe. Authors Grady Hendrix (the best-selling "Southern Book Club's Guide to Slaying Vampires" and "Paperbacks from Hell") and Chris Poggiali (historian and creator of the "Temple of Schlock" zine and blog) dive deep into the labyrinth of Hong Kong moviemaking to detail the rise of figures like Lee, Chan, and lesser-known and more infamous talents, as well as the moviegoers who lived, died, rallied against, and profited by their on-screen heroics.

This crew included a diverse coterie of Black, white, Latino, and Asian martial artists, distributors, eccentrics, authority figures, and more than a few artists who drew inspiration from martial arts. "Bricks," in particular, delves into the inspiration drawn from martial arts by Black artists, who brought the energy and spectacle into their own work — like rapper/producer/filmmaker RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan (who drew their name from the 1983 feature "Shaolin vs. Wu Tang"), and who pens the book's introduction.

Looper recently caught up with Poggiali and Hendrix to discuss the book and marvel at some of their wildest stories about '70s and '80s martial arts, drawn from and verified in the pages of "Bricks."

The Chinese Boxer and Lady Kung Fu: two Hong Kong superstars before Bruce Lee

To many casual fans of the genre, Bruce Lee is the alpha and omega of '70s-era martial arts cinema. However, there were many martial arts performers who scored substantial screen hits in their native countries and the United States before he broke wide with 1971's "The Big Boss." Among them were Taiwanese actor Wong Yu, star of the early Shaw Brothers hit "The One-Armed Swordsman" (1967), who helped to shift Asian action films from wu xia (heroic swordsman) movies to blood-soaked martial arts brawlfests by writing, directing, and starring (as Wang Yu) in "The Chinese Boxer" (a.k.a. "The Hammer of God") in 1970.

A year later, another Taiwan native — Chinese Opera school student Angela Mao — signed with ex-Shaw Brothers exec Raymond Chow's Golden Harvest to become a rare female lead in numerous features, including "Hap Ki Do" (a.k.a. "Lady Kung Fu") and "Lady Whirlwind" (a.k.a. "Deep Thrust"). In her films, Mao displayed astonishingly athletic fight skills, many choreographed by Jackie Chan collaborator and future US TV star Sammo Hung.

Both Mao and Wong Yu remained popular stars in the Asian and U.S. markets for several years. As "Bricks" co-author Chris Poggiali tells us, "A good way to gauge the popularity of an international star is to see if a major Hollywood studio released one of his/her films — so the fact that MGM put out (Mao's) 'Deadly China Doll' and 20th Century Fox backed (the Wong Yu film) 'The Man from Hong Kong' gives some indication of the worldwide box-office clout of Angela Mao and Jimmy Wong Yu during the mid '70s."

Their successes were overshadowed by Lee's brief-yet-meteoric rise, even though Mao would play Lee's doomed sister in "Enter the Dragon." Wong Yu moved on to increasingly lesser pictures (in "Bricks," he's quoted as saying, "I don't think any of my films are good") and suffered a string of personal setbacks before returning to movies for a short period of time in the 2000s; Mao left acting in early 1980s and oversaw several Taiwanese restaurants in New York City.

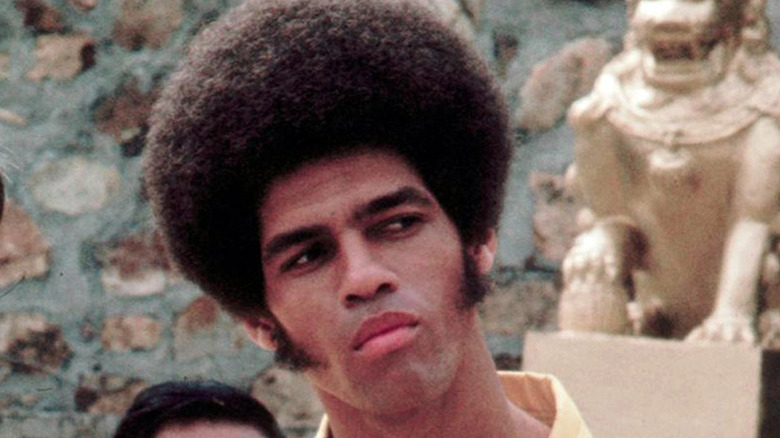

Jim Kelly, Ron Van Clief, and other Black martial arts stars fought an uphill battle

One of the primary through-lines in "These Fists Break Bricks" is the connection between martial arts and the Black community, which embraced both the self-defense disciplines and the movies themselves. The book details the lives and careers of early Black martial arts champs like Victor Moore, Sijo Muhammed, Owen Wat-son, and Dennis Brown, who faced personal and professional challenges throughout their lives. As co-author Grady Hendrix explains, "Karate champion Victor Moore couldn't compete in whites-only venues."

"Despite deep roots in the Black community, Black martial artists faced an uphill battle," adds Hendrix. Jim Kelly cut a fly figure opposite Bruce Lee in "Enter the Dragon," but found it impossible to find career traction outside of low-budget fare like "The Tattoo Connection." Hendrix also notes that the powerfully built and charismatic Ron Van Clief — who studied under pioneering Black martial arts teacher Moses Powell — "never had a single movie produced by a major studio, finding all his work on indie productions" like "Black Dragon's Revenge," which paired him with skilled Latino martial artist Charles Bonet. "The Puerto Rican Panther," as Bonet was known, also struggled to land movie work and later wound up temporarily homeless and battled drug addiction before gaining sobriety and stability with the help of his former students.

Black martial arts stars in the '80s and '90s fared little better. Taimak Guarriello, a student of Ron Van Clief, came from nowhere to capture the lead in the Berry Gordy-produced "The Last Dragon," only to see stardom ripped away when subsequent film deals fell through. Billy Blanks, who starred in numerous low-budget kickboxing movies, found greater fame as the creator of the Tae Bo cardio program. Today, a handful of Black martial arts stars enjoy varying degrees of fame, including Michael Jai White, Sebastien Foucan, and actors/stunt performers Aaron Toney ("Black Panther"), Bobby Samuels, and Lateef Crowder ("Wonder Woman").

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

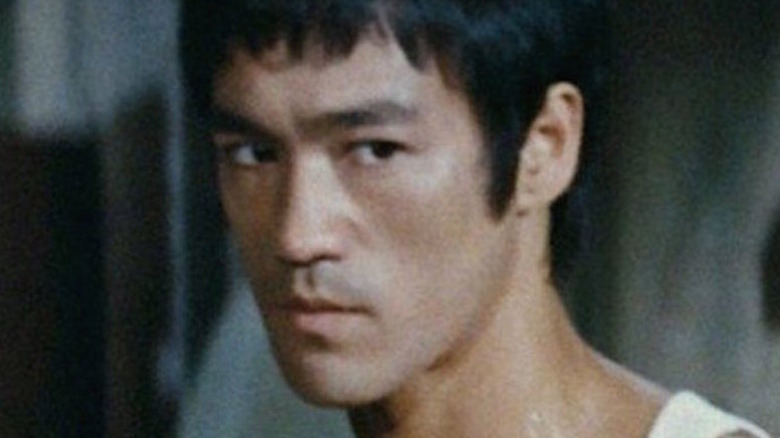

Bruce Lee wasn't a superstar overnight

The popular myth surrounding Bruce Lee is that he was a success in every endeavor he attempted, from martial arts to television and movies in both Hong Kong and America. But the truth, as Hendrix shares, is very different. "When Bruce Lee went back to Hong Kong to appear in some low-budget kung fu movies, he was a washed-up former child actor and C-list television star with a crippling back injury who just needed quick cash to pay his mortgage," he says.

Lee's stint as a juvenile actor in Hong Kong dramas ended shortly before he relocated with his family to the United States in 1959; his impressive physical feats at martial arts tournaments led to a screen test for "Batman" producer William Dozier, who cast him as Kato on "The Green Hornet" TV series. But the show was canceled after a single season and Lee taught martial arts to actors like Steve McQueen and James Coburn while waiting for his big U.S. break. It never came, so he returned to Hong Kong to star in a low-budget action film for Golden Harvest.

That film — 1971's "The Big Boss" (titled "Fists of Fury" for Stateside audiences) — became the highest-grossing film in Hong Kong history, until its follow-up, "Fist of Fury" (retitled "The Chinese Connection" in the U.S.) broke its record. "That those two movies became some of the biggest all-time hits in Hong Kong box office history is a testament to [Lee's] sheer force of will," says Hendrix.

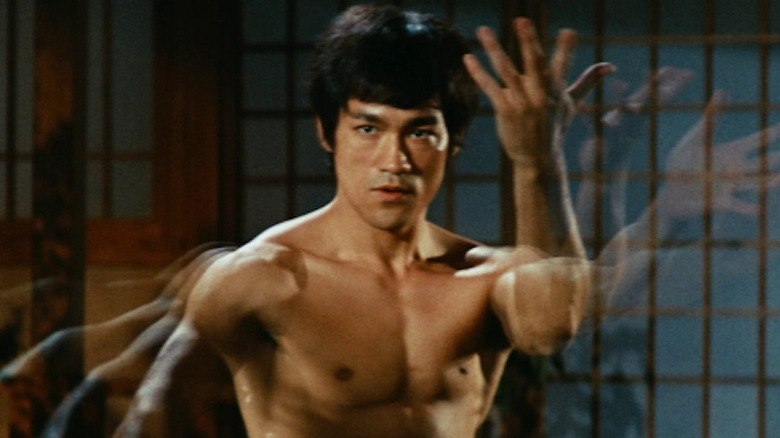

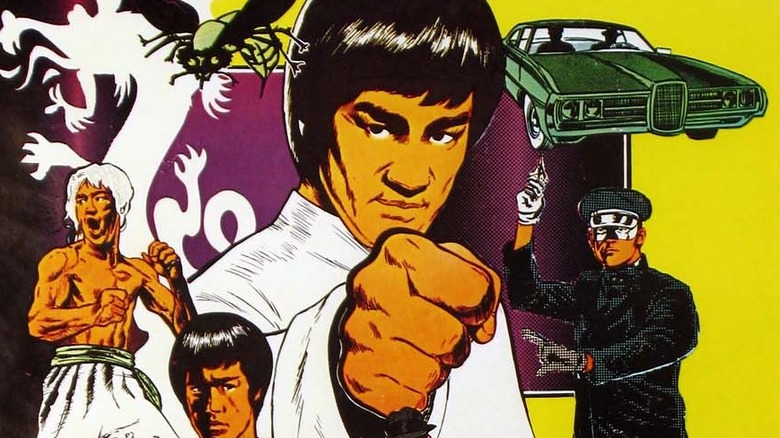

The weird world of Bruceploitation

After establishing himself as a global star with films like "Way of the Dragon" — featuring a pre-stardom Chuck Norris — Lee began work on "Enter the Dragon," his first U.S.-Hong Kong co-production. He died four weeks before its release in 1973, stunning fans around the world. "Bruce Lee worked so hard for so long to become a movie star that his sudden and premature death at age 32 left his growing number of fans wanting more than just four completed films," says Poggiali. "[This] led to numerous imitators and uniquely tasteless examples of supply and demand."

Hong Kong film companies, including Golden Harvest, immediately began cranking out films to capitalize on Lee's fame — and the void left by his untimely death. "Bricks" breaks down the "Bruceploitation" subgenre into three types: biopics, employing a mix of footage of the real Lee (including some taken at his funeral) to tell the "real" story of Bruce Lee; spinoffs, in which Bruce Lee not only lives but also becomes an off-screen hero, battling gangsters, mad scientists, and in the berserk "The Dragon Lives Again," faux versions of James Bond, Dracula, and the Godfather, with Popeye (!) as his sidekick.

The third subgenre, sequels, concerns threadbare follow-ups to Lee's biggest hits, often with actors from the original films appearing with the Bruce carbons like Shih Kien and Bolo Yeung from "Enter the Dragon." Producers tapped a host of actors from Indonesia, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea to play the Bruce carbons, and redubbed them with creative monikers: Bruce Li, Bruce Le, Bruce Leung (who later appeared in "Kung Fu Hustle"), Bronson Lee, Dragon Lee, and Myron Bruce Lee, to name just a few.

Taste and logic rarely mattered in Bruceploitation films; in "Fist of Fear, Touch of Death," footage from Lee's childhood films is awkwardly shoehorned into a baffling plot about the search for the next Bruce Lee anchored by footage from a real martial arts bout in Madison Square Garden, faked street fights with Ron Van Clief, and outrageous narration (by Oscar nominee Adolph Caesar) about Bruce's "samurai grandfather."

A failed Bruce Lee TV series became one of the world's first fan edits

The demand for Bruce Lee movies — any footage of Bruce on film — led distributors to get creative. Case in point: Larry Joachim, a New York-based distributor who specialized in weekend matinees for kids. Among his most successful titles was the 1966 "Batman" feature, which sparked an idea from his young son, Marco.

Marco recalled that "Batman" producer William Dozier had also overseen "The Green Hornet" with Bruce Lee, and being a die-hard kung fu movie fan, suggested to his father that money could be made from the old series. Larry Joachim used his connections with Fox to wrangle 16mm prints of "Green Hornet," which he then turned over to Marco, who watched the prints and cut together a rough print which combined footage of Lee from the episodes into a semblance of a new story.

As noted in "Bricks," the completed film entitled "The Green Hornet" opened in Chicago in 1974 and grossed $45,000 in five days, prompting screenings in many more theaters. Enough footage from "Green Hornet" was left over for a sequel, "Fury of the Dragon," which followed in 1976 and played in theaters for a decade. "There's no mention of either of Marco's "Green Hornet" movies on Wikipedia, even under the entry for the ABC television series," says Poggiali. "Which is a shame, because they're two of the earliest, most widely distributed, and financially successful examples of what is now called a 'fan edit.'"

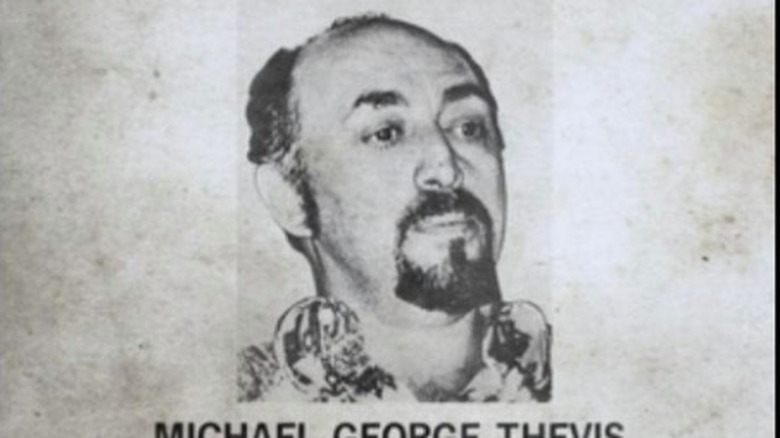

Michael Thevis: the gangster who got into kung fu distribution

"Bricks" profiles a number of the colorful film industry figures distributing martial arts films in the 1970s, including Aquarius Releasing's promotion-savvy Terry Levene, Ivory League Pictures' Ivory Lee Harris — one of the few Black distributors — and Mel Maron of Cinema Shares and World Northal, who brought martial arts movies to TV by pioneering the "Black Belt Theater" programming showcases. However, Georgia-based Michael Thevis took the "colorful" label to new heights — or depths, as it were.

In 1973, Thevis scored a modest box office hit after acquiring the rights to a 1971 Taiwanese film starring Wong Yu called "The Desperate Chase," which he retitled "Blood of the Dragon." "Everyone thought Michael Thevis was a wealthy Atlanta music producer dipping his toes into kung fu movies," says Hendrix. But after the FBI hit him with charges of pornography and arson, "it became clear that he was a homicidal porno king laundering his money through motion pictures," he adds.

Thevis was making millions by overseeing his own peep show booth empire, and wasn't above killing a few people who stood in his way, which included planting "a pipe bomb in a competitor's truck," as Hendrix explains. Thevis went to prison in 1974, but used his connections to Georgia congressman Andrew Young — whom Jimmy Carter appointed ambassador to the United Nations — to secure transfer to a minimum-security prison in Indiana, from which he escaped in 1978.

After murdering Roger Underhill, a former associate who had turned informant to testify against him, in 1978, Thevis earned his spot on the FBI's Most Wanted List. His time in the spotlight was brief: the feds picked him up for trying to withdraw cash under a false identity, and he earned additional convictions while serving a life sentence in prison for telling fellow inmates about the murders he'd committed. Thevis died in prison in 2013.

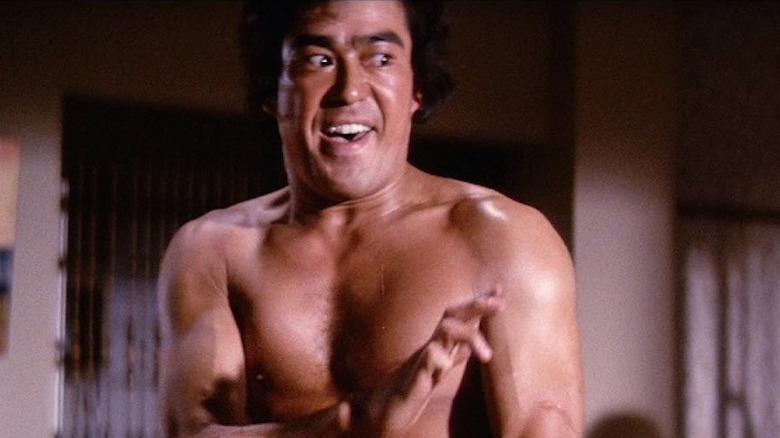

Sonny Chiba was the skull-busting star of The Street Fighter

As with all film trends, the first wave of kung fu movies eventually wound down in the '70s, but not before the release of one of the most outrageous Asian action films. A 1974 article about yakuza movies in "Film Comment" by "Taxi Driver" scribe Paul Schrader convinced New Line Cinema president Robert Shaye that the next big martial arts picture might come from Japan instead of Hong Kong. A visit to Tokyo's Toei Company did yield a gangster movie ("The Tattooed Hitman"), but Shaye also spotted a poster for "Gekitotsu! Satsujin-ken," an action thriller featuring actor Shinichi Chiba.

"Chiba's face was already familiar to some American television viewers thanks to late-night showings of [Japanese science fiction films like] "Invasion of the Neptune Men" and "Terror Beneath the Sea," says Poggiali. Shaye screened the film and was floored by Chiba's near-maniacal anti-hero and astonishingly violent setpieces, including a scene in which the screen image turns "X-ray " to reveal the full devastation of a fist crushing a man's skull.

Shaye bought the rights to the film and gave it to filmmaker Jack Sholder (later the director of "A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy's Revenge") for an English-language cut. Sholder retitled it "The Street Fighter" and dubbed its star "Sonny" Chiba. The MPAA slapped "Street Fighter" with an X rating for violence, which revolted most critics, but audiences flocked to the film and made it a box office hit. New Line released two sequels, "Return of the Street Fighter" and "The Street Fighter's Last Revenge," as well as a related film, "Sister Street Fighter," with Chiba and Etsuko "Sue" Shihomi, Other companies, like Aquarius Releasing, grabbed up more Chiba titles like "Bodyguard Kiba" (a.k.a "The Bodyguard") to further feed his fan base.

As Poggiali notes, "The popularity of karate films like "The Street Fighter" and "The Bodyguard" had grindhouse theatergoers across the U.S. chanting "Vi-va, Chi-ba! Vi-va, Chi-ba!" Chiba himself, who was not a fan of "Street Fighter" (he's quoted in "Bricks" as saying, "I didn't like ripping out vocal chords"), remained active in dozens of Japanese and U.S. action films for decades (including Quentin Tarantino's "Kill Bill: Volume I") before his death from complications of COVID-19 in 2021.

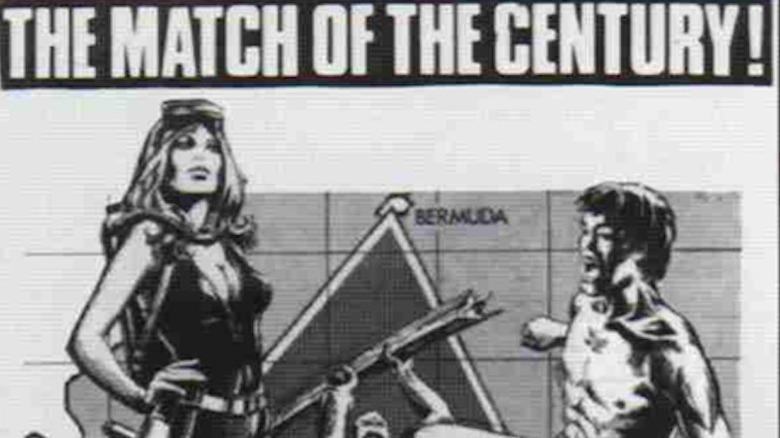

Faux fists: outrageous credits, made-up awards, and martial arts movies that didn't exist

Though Michael Thevis was an extreme exception rather than a norm among film distributors, many exploitation outfits weren't above playing fast and loose with the facts about titles, often to surreal extremes. The aforementioned "Bruceploitation" subgenre is a perfect example, as is the practice of attributing fake awards to their films and stars, like the Ebony Fist Award won by "Playboy" Playmate Jeanne Bell of "TNT Jackson." As "Bricks" shows, "Fists of Vengeance" never won Karate Film of the Year, and China's Grand Master of Kung Fu, Chang Ming Lee, didn't endorse "Iron Fist," because neither the laurel nor the man are real.

"Schlock movie distributors were always on the lookout for new trends to capitalize on," says Poggiali. "Within the martial arts genre, their questionable advertising tactics [included] retitling movies to echo recent box-office hits: "The Chinese Godfather,' 'Kung Fu Exorcist,' 'Kung Fu Halloween,' 'Fighting Convoy,' and so on."

Another entertaining trend was the announcement of movie projects that never existed. The fact that no script, director, or funding was in place didn't stop Boston-based producer/distributor Serafim Karalexis from announcing "Enter Three Dragons," with Dragon Lee and Ron Van Clief and a poster featuring art by legendary comic book artist Neal Adams. Nor did it prevent ads promoting the release of "Ilsa Meets Bruce Lee in the Devil's Triangle," which would have brought together Dyanne Thorne, star of the infamous "Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS" and a Bruce imitator. Unfortunately for exploitation fans, the ad is the only element of the film that came to fruition.

Kung fu didn't always mix well with other genres

Sensing that the martial arts boom was tapping out in the mid-1970s, producers fell back on another tried-and-true method of bringing audiences back to theaters: folding kung fu into other genres. Cross-pollination produced some memorable experiments within the martial arts genre — as "These Fists Break Bricks" illustrates, Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung scored hits by folding comedy into action — but efforts to merge kung fu with other genres weren't as successful. Shaw Brothers saw mixed results by co-producing "The Stranger and the Gunfighter," a martial arts-spaghetti Western with Lee Van Clief and Lo Lieh from "Five Fingers of Death," and partnering with the UK's Hammer Studios for the horror/kung fu hybrid "The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires."

From there, the mash-ups get more dire: Shaw teamed with Warner Bros. for the blaxploitation/action thriller "Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of Gold," while "Enter the Dragon" star Jim Kelly was stranded in crummy martial arts/sci-fi/spy oddities like "Death Dimension." Efforts to release kung fu in 3-D, such as the Taiwanese films "Dynasty" and "Revenge of the Shogun Women," yielded minor returns in the States.

Poggiali sums up the genre hybrids succinctly: "Mixing martial arts with comedy and horror seemed natural in Hong Kong productions, but attempts to combine kung fu with other fading genres like blaxploitation or spaghetti Westerns — even when the hybrids were entertaining — mostly came across like acts of desperation."

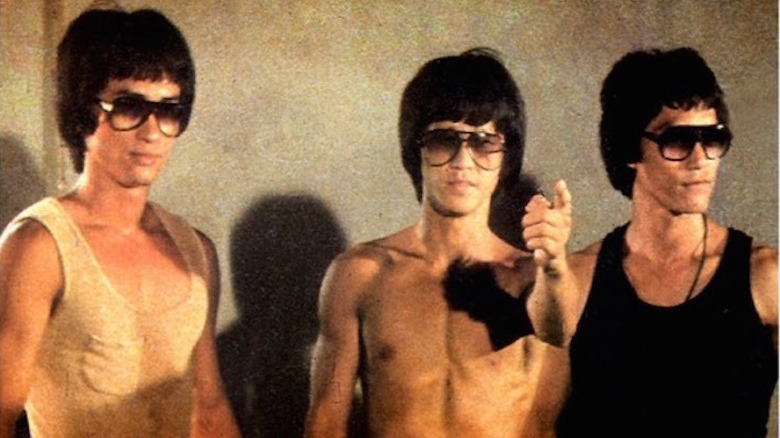

Jackie Chan had his imitators too

Jackie Chan's early career trajectory followed that of Bruce Lee; both men were child actors, and Chan served as a stuntman and minor player in Lee's "Fist of Fury" and "Enter the Dragon." After working his way up to stunt choreographer, Jackie was tapped by producer/director Lo Wei to imitate Bruce in the dreadful "New Fist of Fury," an ersatz sequel to Bruce's breakout feature. Jackie later found his groove with comedy-action hybrids like 1978's "Drunken Master," which led to his ascension as a leading man. After parting ways with Lo Wei — a potentially dangerous scenario because of Wei's connection to triad gangsters, which was defused by none other than Wong Yu — Jackie moved to Golden Harvest and created the jaw-dropping action films that made him a martial arts legend.

Just as Bruce Lee's success generated the Bruceploitation scene, Jackie's popularity spawned what Hendrix calls "an army of imitators sporting helmet-shaped haircuts and doing comedy kung fu." Chief among them, he adds, "Indonesia's Willie Dozan found fame as Chan imitator Billy Chong and Ulysses Tzan [whose "Mantis Boxer" was essentially a scene-for-scene remake of Chan's "Drunken Master"] became the 'Jackie Chan of the Philippines.'" Also on the Chan train: Korean actor Jeong Jin Hwa, who sported one of the best screen names — Elton Chong — while, as Hendrix notes, "South Korea covered all their bases, pairing a Bruce Lee and a Jackie Chan impersonator for 1981's 'Jackie and Bruce to the Rescue'."

Meet the men who wanted to be the next Chuck Norris

Theatrical screenings of martial arts movies took a flurry of roundhouse kicks in the early 1980s. Changing audience tastes, headlines linking kung fu to real life violence, and the collapse of the grindhouse theater circuits from the crack epidemic and greedy developers eliminated many of the venues that played Asian action films. Mel Maron of Cinema Shares and World Northal kept many older titles in circulation through "Black Belt Theater" packages for television, but if you wanted to see the latest martial arts movies in the '80s, your choices were limited; you went to Chinese-language theaters in big cities to see the new Jackie Chan titles, you ponied up exorbitant fees for videocassettes, or you saw Chuck Norris take out truckers and gangsters in theaters.

Norris operated on the fringes of the film industry throughout the early '70s, including a face-off against his friend, Bruce Lee, in "Way of the Dragon." But he vaulted to leading man status with a string of low-budget action films, beginning in 1977 with "Breaker! Breaker!" and enjoyed box office success into the early 1980s. Attention from major studios soon followed, as did a second wave of stardom for Norris as a mainstream star in films like "Missing in Action."

"Once Chuck Norris drifted away from martial arts storylines to more gun-oriented action, a number of new faces appeared on the scene," says Poggiali. Many of these would-be heroes were cut from the same cloth as Norris: Young white men with martial arts backgrounds like kickboxing champion Joe Lewis (rumored to be the physical model for Ken Masters in Capcom's "Street Fighter" game), Loren Avedon (who trained with tournament champ and fight coordinator Simon Rhee), and Kurt McKinney. Each got a shot at kung fu stardom in films, like McKinney in "No Retreat, No Surrender" (with Jean-Claude Van Damme and Kim Tai-chung as the ghost of Bruce Lee!) and Avedon in "King of the Kickboxers," but was quickly supplanted by a new crop of stars, many of whom shared the screen with them in supporting roles.

"It wasn't until the close of the '80s, when solid box-office draws like Jean-Claude Van Damme and Steven Seagal filled the void left by Norris, while Cynthia Rothrock, Billy Blanks, and Don "The Dragon" Wilson became direct-to-video action attractions," says Poggiali.

Take a deep dive into the world of amateur '80s kung fu movies

Martial arts found a comfortable second home on VHS in the 1980s. Older or obscure titles gained new audiences through VHS releases, and the demand for new material gave acting and directing hopefuls a shot at making and releasing their dream projects. "If it was 90 minutes long and in focus, anything with kung fu could turn a profit on home video," explains Hendrix.

Many of these homegrown efforts came from places outside of Hollywood. Missouri-based detective and martial arts instructor Ron White plunked down a little over $12,000 to make 1985's "Justice, Ninja Style," for which he starred as a small town ninja. Jun Chong, who starred in "Bruce Lee Fights Back from the Grave" (as Bruce K.L. Lea), made several ultra-low budget ninja pics, including "L.A. Streetfighters," with the 41-year-old Chong as a high school gang leader and Loren Avedon in a bit role. And Chuck McNeil directed a slew of home movie-styled action films like "Dragonspade" and "Dragon from the East," though the actual existence of several of his films is unclear. "Bricks" includes a quote from "Boxoffice" magazine's review of "Streetfighters," which seems to encapsulate the response to many of these amateur martial arts films: "This is a joke, right?"

But regional filmmakers remained undaunted. Hendrix explains, "[They] delivered low budget cult classics like the chicken-obsessed 'Furious' (1984) and Grandmaster YK Kim's ninja-riffic 'The Miami Connection' (1987), and oddities like Wichita's 'King Kung Fu' (1987) about an escaped, kung fu fighting gorilla who abducts a Pizza Hut waitress and scales the tallest Holiday Inn in town." And if you don't believe that last one is real, here's the trailer.

Ninjas dominate pop culture in the 1980s

"In 1985, America hit peak ninja," says Hendrix. "'Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles' surfed out of the sewers, Remco's Ninja Strike Force dominated toy stores, Parfums de Coeur sold $20 million of Ninja cosmetics, and everyone dressed like a ninja for Halloween."

Ninjas had been on the periphery of movies and television for decades. Professor Ronald Duncan, a Black ninjutsu teacher, performed weapons demonstrations in the New York area in the 1960s and on TV shows like "Thrillseekers" and "The Wide World of Sports" in the '70s, though as Hendrix notes, his efforts were largely ignored, and he was virtually "erased from history."

Ninjas turned up in the James Bond feature "You Only Live Twice" in 1967. But the release of Eric Van Lustbader's 1980 novel "The Ninja" sparked mainstream interest in all things ninja, which was answered by Cannon Films' "Enter the Ninja" in 1980. In the film, Franco Nero — the original "Django" of spaghetti Western fame — played a ninja battling an evil businessman. Few found Nero believable in the role, but Cannon chiefs Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus saw a new star in Sho Kosugi, who played an evil ninja.

A martial arts teacher and minor actor in Bruceploitation films, Kosugi briefly became the go-to screen ninja in the 1980s, though his early showcases for Cannon were underwhelming, or in the case of "Ninja III: The Domination," downright bizarre. He parted ways with the company in the mid-'80s to oversee his own films for Trans World Entertainment, including the box-office hit "Pray for Death."

Cannon rebounded with "American Ninja," a vehicle intended for Chuck Norris which instead became a star-making project for former model Michael Dudikoff, who, as Hendrix says, "discovered the ancient teachings of his ninja heritage" in the film. This ludicrous effort was followed by four more "American Ninja" titles, but ninjas retained their hold on martial arts fans and pop culture through toys, costumes, video games, action figures and other ephemera until the early 1990s.

How to make 10 ninja movies for nothing: a master class in cheapness from Godfrey Ho

In a subgenre where plot cohesion often took a back seat to smoke bombs and color-coordinated costumes, the ninja films of director Godfrey Ho stand out as some of the most confusing, haphazardly made titles in the martial arts genre — or any genre, honestly. Ho cut his filmmaking teeth at Shaw Brothers before teaming with producers Joseph Lai and Tomas Tang of Intercontinental Film Distributors (IFD) to crank out dozens of low-budget action films in international markets — territories that, as the "Bricks" authors note, were largely ignored by other Hong Kong filmmakers — proliferated by the VHS boom of the 1980s.

The success of "Enter the Ninja" spurred IFD to produce their own ninja films, many starring American actor Richard Harrison, who had been a major star in Italian Westerns and spy films in the 1960s. It didn't matter than Harrison had no (apparent) martial arts abilities; the full-body ninja costumes allowed them to use doubles for the action scenes. Though Harrison technically appeared in four IFD ninja films, including 1984's "Scorpion Thunderbolt," he later learned that Ho had edited footage of him into at least a dozen additional ninja films, each more baffling than the other.

"Godfrey Ho was the mad motion picture scientist, grafting one ninja film onto another, making knock-offs and rip-offs full of Garfield phones, doofus dubbing, color-coded ninja outfits, and an approach to storytelling logic that borders on the criminal," explains Hendrix. "He always wanted more. More ninjas! More explosions! More everything! As he said to his actors, 'I can't see your acting — more acting!'"

IFD later turned its attention from ninjas to kickboxing after the success of Cannon's "Bloodsport," with Jean-Claude Van Damme — whom Ho and company nearly signed up when the Belgian martial artist (then known as Jean-Claude Van Varenberg) dropped off a headshot at their Hong Kong office. Ho later parted ways with his IFD partners and worked in films with Cynthia Rothrock, among others, while enjoying cult status among fans of the cinema of the truly bizarre.