That's What's Up: The Most Important Scene In Batman: The Dark Knight Returns

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: I've heard you say that the best scene in Frank Miller's Dark Knight Returns is not the one that people expect. If it's not the mud pit scene, what is it? — @benito_cereno

Over 30 years since it originally hit shelves, and The Dark Knight Returns is still one of the most influential Batman stories ever published—which, in pop cultural terms, probably makes it one of the most influential comics of all time, period. And it's also one of the most imitated. You can see huge sections of it recreated in live action in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, but it's not just the specific moments and individual panels that were brought to life. It's the themes, the way the characters talk to each other.

And yet, with three decades of comics, TV shows, and movies all attempting to recreate, react to, and reject DKR, there are very few that manage to even come close to capturing the feeling of what seems like one of the book's smallest moments: two panels in the second issue that aren't just the best moment in Dark Knight Returns, but might be the single best moment of Frank Miller's entire career.

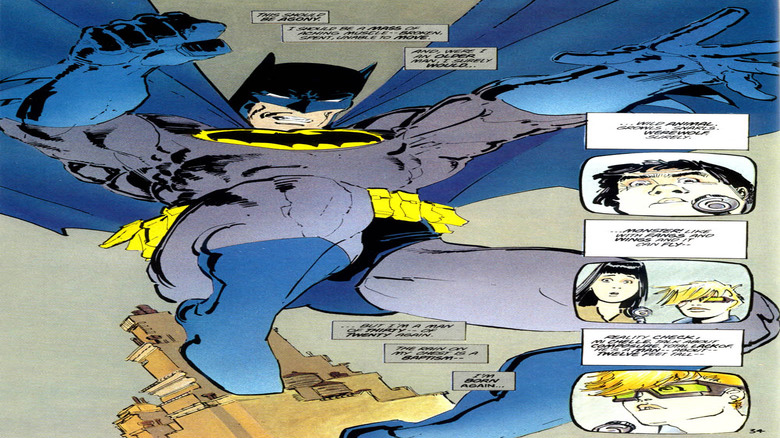

The rain on my chest is a baptism...

If that sounds like a bold statement, it is. DKR is, after all, a book that's full of great moments. It's one of the reasons that it's still held up as a cornerstone of the comics canon even after 30 years of diminishing returns from creators—including Miller himself—attempting to recreate its initial success.

But honestly, there's a good reason for that. DKR's most memorable scenes have this incredible fist-pumping gut-punch that inspire a feeling it's hard not to want to recreate. A retired Bruce Wayne realizing things have gotten so bad in Gotham City that he needs to come out of retirement and feeling that first rush of being Batman again? That's an incredible moment, and the prose that accompanies it—"the rain on my chest is a baptism"—is definitely a little over the top, but it's the kind of soaring, almost operatic sentiment that the superhero genre does so well.

It's not just the thrill of recaptured youth, although that's something that was undoubtedly important to Miller. He writes in his introduction to the DKR paperback that his primary motivation for doing a story about an aging Batman was the realization that on his 30th birthday, he was about to be older than Batman's official and eternal 29. It's more than that. It's the idea that being Batman is awesome. It's a rush, this idea that you can become something more than yourself, embodying an idea that allows one person to surpass the physical tolls that we all face as we grow older and single-handedly wrench a crime-ridden city back from the brink of self-destruction. It's a problematic power fantasy, to be sure, but it's pretty easy to see the appeal.

It's not the best moment in the book, though. And neither is the scene in the mud pit.

This isn't a mudhole...

That's the one that people usually go to, and to be fair, it's pretty great. "This isn't a mudhole, it's an operating table... and I'm the surgeon" is probably the most amazing, hilariously over-the-top bit of hard man dialogue in comics history. It's the perfect combination of menacing and silly that you want from a guy who's built like John Cena and dressed up as Dracula for the sole purpose of punching out criminals. More than that, though, it works not just because it's Batman saying it, but because of who Batman's saying it to.

To say that the Mutant Leader is cartoonishly evil is underselling things by a fair bit. By this point in the story, he's threatened to murder the entirety of Gotham City, decapitate Commissioner Gordon, and literally eat Batman, on top of other, arguably worse threats. He's every bit the embodiment of an older person's fear of young criminals and their abject amorality, something that was prominent in the '80s crime wave that informs so much of DKR. He's the bad kid from Class of 1984 jacked up on horse steroids and so devoid of fear that he tries to fistfight a tank. And here we have Batman, absolutely crushing him in in a mudhole.

The thing that often gets lost in the discussion of the "hell yeah" moment of the scene, though, is that this is actually the second time they'd fought. The first time, Batman doesn't just lose, he's destroyed. The Mutant Leader is younger, stronger, more ruthless, and, crucially, completely unafraid, robbing Batman of the ability to intimidate and terrorize his opponents in the way that gives him an edge.

It's a nice little bit of plotting—you can't get behind a protagonist out to avenge a defeat if he doesn't have the defeat first—but the important thing is that the entire reason Batman even survives that first fight is because of one unexpected factor: Carrie Kelly.

Real good, Carrie...

Carrie Kelly is the most interesting character in this story by a long shot, and a lot of that comes from how the ideas she represents interact with everything going on around her.

Despite the story's portrayal of Ronald Reagan as a doddering figurehead who passed out medals like mints and manipulated Superman into acting as an obedient government stooge—which led in turn to one of the more unfortunate pieces of DKR fallout, in that arguably one of the worst portrayals of Superman was as influential on his books as it was on Batman's—there's an unavoidable streak of conservative fear at the foundation of The Dark Knight Returns. It leads to Miller's later, much more unfortunate work, and it's that same fear of youth you can see embodied in the Mutant Leader, a romanticization of the past and how things used to be better, and how things right now are so bad that it requires one person—let's be real here, one man—willing to tear down the system and put things back in order with ruthless brutality. It's the reason this book opens with Batman kicking a bank robber (who is, of course, a drug-addled pill-head) so hard that he breaks his spine.

The thing about DKR, though, that separates it from similar power fantasies (and, at heart, from Miller's own later work) is that that approach doesn't work. It does for a minute, with a blitz on crime that serves as something of a triage for Gotham's truly terrible state, but it's not sustainable.

Carrie Kelly and her predecessor

Carrie Kelly changes that.

At the start of things, it's easy to see her as a product of that same right-wing power fantasy. Her parents are, after all, the broadest possible caricatures of aging hippies, too caught up in smoking weed and wringing their hands over the consequences of the police state to notice that their daughter is dressing in a superhero costume and sneaking out at night to help Batman wage a war on crime. The defining moment of Carrie's home life comes during that scene in the junkyard when Batman first fights the mutant leader; we cut back to her apartment for two panels, and her parents, always unseen, take a moment between tokes to ask "didn't we have a kid?" as smoke curls up between their word balloons.

On one level, you could read Carrie's rebellion and the way it's presented to us as stemming from the same fear of youth that inspires the Mutants'. It's just the flipside to the same coin, with Carrie's rebellion being something that we're supposed to like because she's rebelling against bleeding-heart parents, an act of defiance directed at people so characterized by ineffectual talking that they're only ever seen as dialogue. I don't think that quite covers it, though, and not just because virtually any form of teenage rebellion is preferable to one that involves, you know, threats of cannibalism.

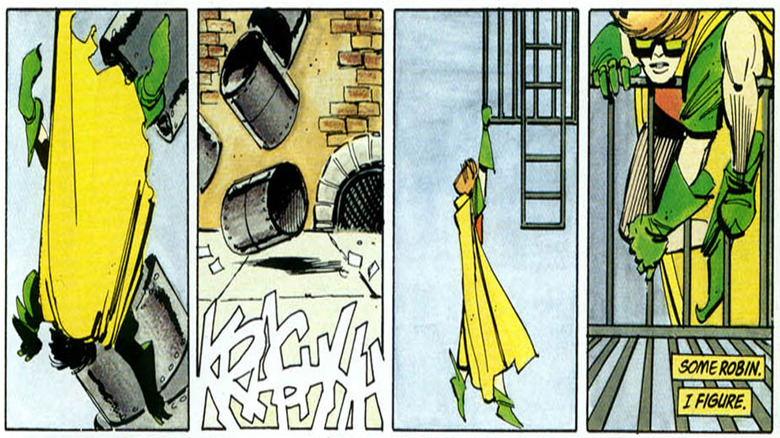

Some Robin

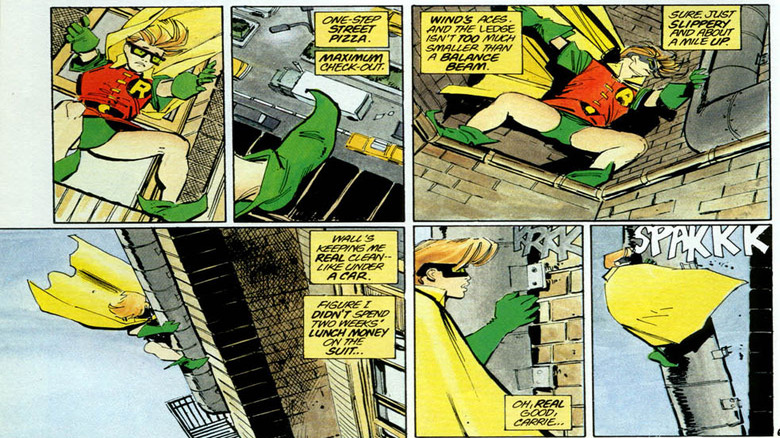

What it comes down to is that Carrie's journey mirrors Batman's in a really fascinating way. Just look at her first act after she puts on the costume: she nearly kills herself by falling off a ledge, only catching herself on a fire escape.

It's a pretty ignominious start, but there's a reason for it. When Miller and David Mazzucchelli followed up Dark Knight Returns by reinventing Batman for a new generation in the equally influential Batman: Year One, we see the same thing happening to Bruce Wayne. The first time we see him in the Batman costume, the first time he appears on the page at all after a bat crashes through his window, it's with a disastrous attempt at fighting crime that finds a teenager almost falling off a fire escape. Batman's on the other end of that one, sure, but there's a connection there that has to go beyond the simple fact that fire escapes are a good place to set action scenes when you're telling a story set in a big city.

Oh, and in case you're wondering? Her second act in costume is to break up a game of Three-Card Monte by setting off a firecracker in the dealer's back pocket, which might be the most childish possible version of the idea of fighting crime. Her third act is to save Batman's life.

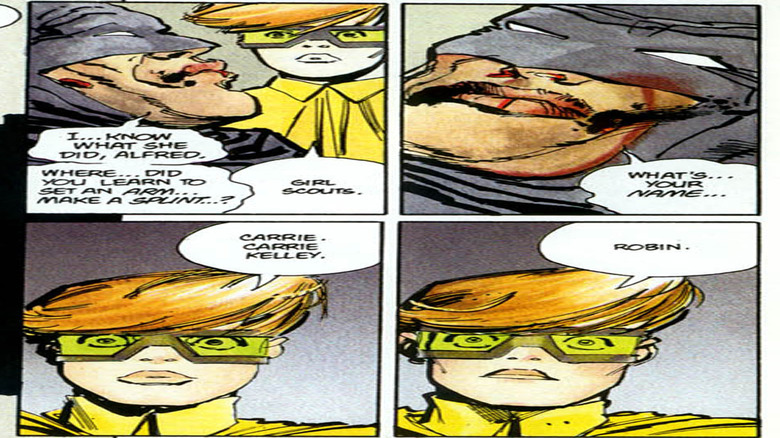

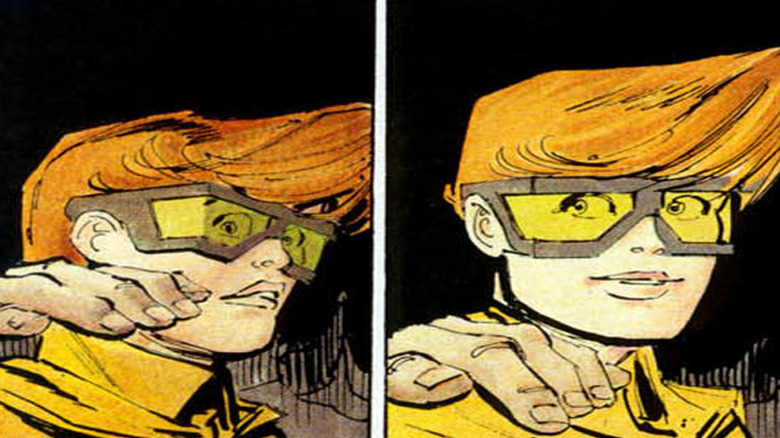

And that's when it happens. The single best moment in Dark Knight Returns: when Batman asks her what her name is.

What's your name...

The thing about Batman that makes him work as something that's more than just a power fantasy resides in the idea of a kid who gives up his life to a higher cause. It's the core of the idea, it's what allows us to believe he's on the same level as an alien who can launch himself over mountains and throw a car into the sun, or an Amazon possessed with genuinely mythical strength and speed. It's the determination to become something more than you are, to surpass your own limitations and exist not as a person, but an idea.

It's a familiar refrain from Christopher Nolan's Dark Knight movies, but it's been there ever since Bill Finger and Bob Kane gave us Batman's origin in Detective Comics #33, with the line that Miller and Mazzucchelli repeated in Year One: "I shall become a bat." It's a decision to take on a new identity. That's what Carrie does here.

And honestly, it probably owes as much to letterer John Costanza as it does to the art team of Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley. The way he leaves so much air in her word balloons, making her voice seem small—a marked contrast to pretty much every other sound presented in this comic—but still definitive. The real magic, though, is the beat between those two panels. It's the set of her jaw, the way that even with the smallest voice in the book, she's ready to say definitively who she is. After that moment, she's no longer Carrie Kelly.

She's Robin.

Robin

Like Batman, she chooses an ideal to become, a symbol that's greater than herself. And in doing so, she's directly responsible for saving Batman—not just his life, but the idea he represents. And like Batman, she knows that for all the talk of One Man Making a Difference, no one can do it alone. That's what makes Robin work as a concept, and it's why Carrie isn't just a good addition to the story, but a necessary one.

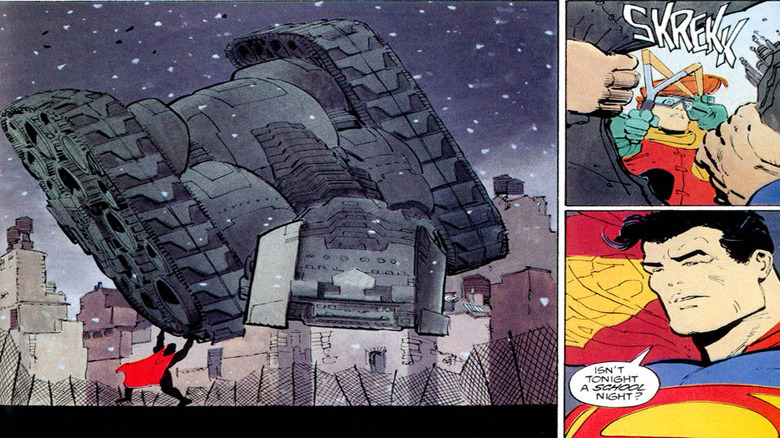

On a functional story level, it's Robin's presence that saves Batman from the Mutant Leader, that convinces him he needs to outsmart his opponents rather than just slamming against them in the hopes that he'll be able to pull off the same physical feats he did when he was younger. It's Robin's presence that shifts Batman's internal narration from "this would be a good death" to "this would be a good life," an often overlooked piece of the story that gives Batman his best possible ending—no matter what any sequels to this story would have you believe.

Oh, and it's also Robin who's directly responsible for Batman beating up Superman at the end.

Isn't tonight a school night?

Thirty years of comics have tried to recreate the feeling and intensity of this fight, and none of 'em ever throw in the best moment. Well, maybe second-best. That scene does have Batman hooking himself into the power grid so he can literally punch Superman with the entirety of Gotham City, and I'd be lying if I said that wasn't pretty great.

Still, it's Carrie Kelly who makes the story work. She's the one who settles the debate that rages in the background of the story for four solid issues, answering the question of whether Batman works. The answer, of course, is that he does—not because he punches out Superman or props up the existing social order, but because he can inspire someone to become more than they are. Even in the fiction of the comics, that's something real, and it's something that Carrie Kelly—Robin—embodies. And it all comes back to that small, quick moment where she sets her jaw, looks Batman in the eye, and answers a simple question: what's your name?

In a story full of memorable moments, that's the best one. There's nothing in Dark Knight Returns that even comes close, not in the narrative, not in the structure, not even in the pure crowd-pleasing action scenes of Batman brawling in a mudhole, busting through drywall, or driving around in a giant tank shooting rubber bullets at terrifying mutants. It's the moment that connects this story to the larger truth of Batman, that holds up even after years of repetition that have left vast sections of DKR feeling like a dated product of its time.

Didn't suck.

And unfortunately, that also makes it the hardest piece of the story to replicate. DKR's incredible influence on superhero comics in general and Batman in particular, and the desire of countless creators to recapture that same feeling, always winds up going for the easy stuff instead. We see Batman growling about punks because it's easy, and we see Batman fighting Superman because that's an easy fight to give readers and remind them of how much they liked seeing it here. Even that fight in the mudhole, with its well-done choreography and the growly tough-guy dialogue that goes along with it, is actually pretty easy to replicate, if you try hard enough.

What's not easy is building the genuine emotional connection that makes a character work and changes everything about the story they're in just by virtue of their presence. What's not easy is capturing the underlying appeal of something like Batman in a single moment, one that's still inspiring even if you're looking at after decades, through all the cynicism that surrounds it. That's difficult.

And this book does it in the space between two panels.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."