Films The Studios Don't Want You To See

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The harsh truth of the film industry is that before they're entertainment, movies are business investments. Money is sunk into a production in the hopes that enough viewers will turn out for it to turn a profit—and in the best-case scenarios, this results in great art, thrilled audiences, and happy producers.

But sometimes a movie can be so bad, so bizarre, and so damaging to the reputation of a studio that the people in charge will willingly torpedo distribution, keeping it away from audiences and writing it off as a lost cause. Some movies are buried for weirder reasons, for legal purposes, or for the sake of someone's ego. Many have gained considerable reputations due to their unavailability, but thanks to the internet, more and more of these buried features—some of them true hidden treasures—are coming to light. Read on to see some of the most notorious movies that, if the studios had their way, the public would never get to see.

Rad

Stories of scrappy underdog sportsmen struggling for a title shot have timeless appeal for audiences, and in the '80s, they were told with more bombast than ever. Released in 1986, Rad follows a young, unsigned BMXer striving to come out on top in the world's greatest off-road bike race—and it's awesome with a capital A. The camp value on this treasure is off the charts.

Reviewers hated it for its stilted performances, inexplicable plot, and modest budget, with the climactic bike race, as one example, staged in what looks like a small-town park with all of the trappings of a 4th of July barbecue. Viewers with a healthy sense of irony, however, can find plenty to appreciate, such as a scene in which characters take their bikes to the school dance—and the dance floor. Rad may fail at what it's trying to do, but it goes above and beyond as a relic of its era, and is well worth tracking down. It was popular as a rental in the days of VHS, but the studio has all but abandoned it since—unfortunate, considering its growing value as an examination of '80s culture at its most kickass.

Martin

One of the late George Romero's best and most interesting horror movies is also his hardest to track down. You can find a copy of Night of the Living Dead anywhere (it's literally in the public domain), but if you want to legitimately see Martin, you'll have to pony up for an out-of-print DVD.

The story of a young man in Pittsburgh who may or may not be an ageless vampire, Martin is a movie that sticks with you. Its hero, who himself appears unsure as to whether or not he is a monster, is sweet and sympathetic, which makes the scenes of him drugging, cutting, and drinking the blood out of people all the more disquieting.

It's not the quality of the film that keeps it out of viewers' hands, because it's actually quite highly regarded. As is common with these sort of entanglements, the reason it's not available is reportedly because the producer who owns the rights for its release simply isn't allowing it. Regardless of the reason, it's a shame it's out of print. It's a unique, wonderfully crafted take on the vampire fable, an example of how to remix old monster stories in a hauntingly effective way—in a way, the anti-Twilight.

The Last Movie

There's a lot of interesting things going on in Dennis Hopper's second feature, 1971's The Last Movie—including the coked-up Peruvian setting and the stuntman vocation of Hopper's protagonist. The problem is, they're not presented in an interesting way. You really can't fault Universal Pictures for burying this movie, releasing it to a small number of theaters for a couple of weeks and never releasing it on DVD; Roger Ebert wasn't kidding when he summed it up as "a wasteland of cinematic wreckage." It's even edited out of order to the point of incoherence—the title card for the movie doesn't appear until 26 minutes in.

A few viewings could help you cobble together the meaning of the movie, which follows Hopper's character as he goes native in Peru and contends with locals who can't tell that movies aren't reality, but it's a joyless, aggravating experience, from the confusing beginning all the way up until the movie ends with a handwritten "END!" card that lands like a poke in the eye. Despite the critical shellacking, and the fact that the film's DOA performance kept Hopper out of the director's chair for nearly a decade afterward, Hopper supported the movie up to his final days, screening it on his own while trying to secure a home video revival.

A Fistful of Fingers

English director Edgar Wright has made a name for himself with his kinetic, detail-obsessive filmmaking, the sort of craftsmanship that rewards repeat viewings. But his first feature has barely seen the light of day, and those who have seen it say the reason is clear: it's too amateurish to be worth it. Empire notoriously gave the movie a lacerating one-star review in 1995, and one otherwise positive write-up from a writer who has seen it allows that the English director's low-budget western spoof is "clearly the work of a young filmmaker just starting out."

Considering the heights Wright has reached since, with critical acclaim and cult appeal surrounding all of his subsequent projects, it's only natural to wonder just how good he was at the very beginning of his career. It's also easy to understand why he would be inclined to keep it out of wider circulation—Wright himself has said the fruits of his efforts disappointed him. "I remember having a meltdown during editing, because I suddenly realized the film wasn't that great," Wright said in an interview with Empire. "And it hit me: I can never make my first movie again."

Naturally, audiences are eager to judge the quality for themselves, and occasionally they can, at the sporadic screenings that Wright has hosted. Perhaps the film has grown more charming with age—amusingly, Empire extended a "formal apology" to the director in 2010 for their initial harsh critique.

Let It Be

The film that captured the Beatles struggling to recapture their chemistry, Let It Be has developed a reputation over the years as a portrait of a band dissolving. In reality, it's not so explosive as has been implied, unless you were naive enough to think the bandmates never bickered. While it may have been a bummer at the time, with decades of distance, the movie is an interesting, loosely-constructed chronicle of the recording sessions leading up to their legendary final rooftop performance. It doesn't make anybody look good, but it doesn't make anyone look that bad, either, and any Beatles fan is apt to find something intriguing in the film's many little moments.

Whether it's the implied drama of Yoko Ono lurking at the fringes of the studio or the way the band lights up when it comes time to play some music, it's an intriguing document, with the rooftop performance serving as an unlikely swan song to one of the most successful musical runs of all time. So why hasn't it ever been released on DVD or Blu-ray? While it has consistently been repressed through threat of lawsuit by its image-conscious cast, the reality today is that for a layman audience, the movie's just not good, with an aimless structure and—most crucially—lousy sound. It's a fans-only experience of a depressing time that a lot of fans probably wouldn't care to see.

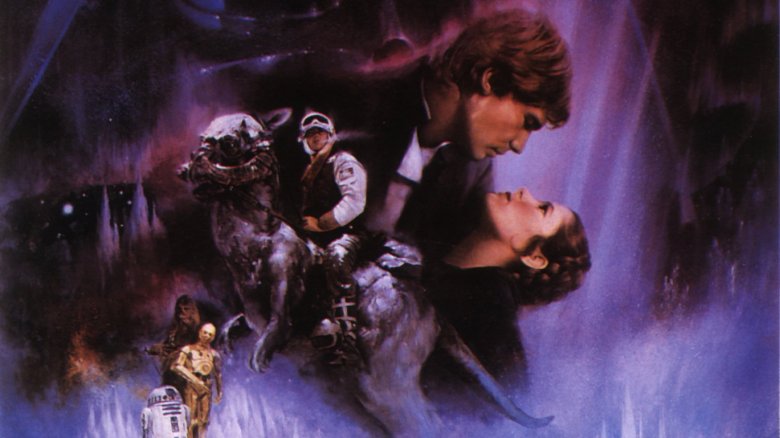

Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back, and Return of the Jedi

In what is perhaps the biggest, strangest case of cinematic injustice on this list, the original three Star Wars movies—undoubtedly some of the most influential films of all time—are extremely difficult to find and see in their original form. As has been well-documented by baffled film historians for decades now, each release of the movies has shown inexplicable, incremental changes in their content and presentation, all in the name of hewing closer to what has been called George Lucas' original vision, with the most egregious examples being the Star Wars special editions, released in 1997 in an overt attempt to replace, rather than complement, the movies as they originally existed.

The painful irony is that as those special editions were developed, it became increasingly harder for actual, original versions of the movies to be found, to the point that when a copy turns up, it's a momentous occasion. The absence of official releases has led to fan edits of the special editions, which keep the cleaned-up visuals and sound while ditching the extraneous junk. The fact that fans have had to do this with some of the highest-grossing, most culturally-embedded movies ever is nothing short of absurd, and the day Disney releases the originals in a restored format will be a cause for celebration.

The Star Wars Holiday Special

The Star Wars Holiday Special has a legendary reputation in the annals of bad entertainment, so far afield from what makes the franchise great that it boggles the mind. Released after the success of the first movie, this largely plotless, overlong, and aggressively unentertaining slog poses itself as a variety show in space, which leads to surreal moments like Bea Arthur singing to aliens in a cantina, Wookies watching hologram gymnastics, and the regrettable debut of the late Carrie Fisher's singing voice.

It's frequently reported that George Lucas has said that if he had the time, he would destroy every copy in existence, and someone should've let him. Ironically or not, there is no fun to be had here. The Star Wars Holiday Special's biggest problem is that it commits the cardinal sin of the crappy movie: it's not just bad, it's boring.

The Ewok Adventure and Ewoks: The Battle for Endor

Less notorious than the despised Holiday Special, these movies are interesting apocrypha in that they're aesthetically similar to the Endor scenes from Return of the Jedi, with music reminiscent of the trilogy and actor Warwick Davis returning in the role of an Ewok. The problem? Well, the Ewoks are back, more articulate than they were in Jedi, palling around with a stranded human family and speaking pidgin English to them as they roam the world. Even that's tolerable compared to the decidedly non-Star Wars plot turns both movies take.

The first film, Caravan of Courage, starts to go off the rails about 30 minutes in, with a magical pond that traps people inside of it, fairies made of light that look straight out of a bootleg Legend of Zelda knockoff, and the unbearable moral message that love is the strongest force in the universe. Its sequel, The Battle for Endor, immediately goes full oddball with the introduction of a malevolent shapeshifting sorceress whose outfit looks like something the costuming department on Xena: Warrior Princess would've rejected as too tacky, as well as a horrifying Alf-like alien that lead actor Wilford Brimley's character lives with in the woods.

Easy to make fun of, they're entertaining watches with the proper mindset, but are they actually good? Absolutely not. They're amusing diversions, tedious at times, but rarely painful. Hey, even the prequels can't live up to that standard.

The Carter

This documentary is a fairly straightforward look at the life of the rapper Lil Wayne, recorded around the the release of Tha Carter III in 2008. What makes it such an interesting document is how revealing it is—it's remarkably unflattering to its subject, and the damage is all self-inflicted. Even as it demonstrates how genius-level talented the rapper is at what he does, Wayne's selfishness, self-destructive habits, and personal rudeness make him a very difficult figure to like. A look into the mind and life of an artist you would probably never want to meet, it's a great watch, and though it's been sporadically released on iTunes, it's currently not officially available, with legal challenges from Wayne's camp blocking the release of the film.

Song of the South

Disney has a reputation for making its catalog of classic films artificially scarce a la the "Disney Vault," but this is one movie they have no interest in releasing widely again. What's the problem? An extremely uncomfortable racial message. Though the notion of the movie taking place during the times of American slavery is a misconception, the reality isn't much better. This is radioactive material, and Disney's portrayal of the South post-Civil War as a chipper place where everybody gets along is a disingenuous portrait of history at best, and terribly offensive at worst.

Even at the time of its release, the movie was excoriated for trafficking in clichés about black people. Today, it's nigh impossible to watch scenes of black people cheerfully tending to the farm work on a plantation while white people cavort around at leisure without feeling a certain level of disgust. These are not the emotions a Disney movie is meant to generate, a fact of which the studio is more than aware.

That kind of content, combined with the unarguably charming Disney animation and all-time classic tunes like "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah," makes for a mind-bendingly dissonant watch, and while the film should be available for its historical value, it's not shocking at all that Disney doesn't want it to re-emerge. To this date, it's never been released officially on home video in the United States. In all likelihood, unless Disney experiences a drastic change in its artistic mission, it never will be.

Glitterati

Roger Avary's adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis' The Rules of Attraction is an underappreciated dark comedy, bearing a loose and loopy structure filmed with daring stylistic touches. One of the more memorable sequences is in the middle of the film, when a world-travelling character named Victor recounts his extensive European travels in a breathless, kinetic montage.

Though the sequence barely lasts four minutes, Avary reportedly shot days worth of footage for it, with Victor's actor staying in character as he takes drugs, seduces women, and otherwise behaves like the alpha and omega of the boorish American tourist archetype. Avary assembled this footage into its own movie, Glitterati, which is one of the more legendarily hard-to-see films from recent years, which author Ellis describes as "like a documentary with a fictional character in the middle of it."

Lionsgate Films distributed The Rules of Attraction, but not Glitterati, and the reasons come down to what is likely a combination of quality and legality. According to Ellis, "for many legal reasons, it will never see the light of day. You can't really show Glitterati in public, it's not possible. There are a lot of people who would be very upset." Avary himself has called the process of making Glitterati "insane" and "ethically questionable"—to this date, he has only showed the film at screenings that he hosts, and the chances of that changing anytime soon are vanishingly small.