Details You May Have Missed In The Original Texas Chain Saw Massacre

Almost 50 years later, "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" has lost none of its power — and not just because Hollywood keeps cranking out sequels. It changed the direction of horror forever, jerking it out of the misty world of old dark houses and supernatural threats and straight into the everyday world of its teenage target audience. In other words, director Tobe Hooper helped invent the slasher subgenre.

And even after half a century, none of the movie's hundreds of imitators are anywhere near as scary. The movie takes its time building its sun-drenched atmosphere, at once grungy and gorgeous, so vivid you can smell the sweat and scorched grass. But once the killings start, the tension doesn't let up for a second.

It's one of the leanest, most efficient scare delivery systems ever made. And even more incredibly, it brings the trashy goods while still having its mind on higher pursuits, creating a statement on American life that can be, and has been, endlessly analyzed even at the highest levels of academia. There's enough going on in "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" to reward watching it over and over again — if your nerves can stand it. Hooper and his small crew may have made the movie on the quick and cheap, but that doesn't mean they didn't take care to pack the frame and the story with plenty of deeper details to unpack and explore. Here are a few to get you started. (Warning — there are spoilers below.)

The radio suggests there's a lot more horror than Leatherface

It'd be hard to call the film's opening scene of grisly corpses subtle, but while that's in the foreground, the radio playing in the background suggests something even more horrifying. It describes the grave robberies along with a laundry list of other disasters: oil fires, a cholera epidemic, a baby chained in an attic, and a random outbreak of mass violence in Houston. The reporter jumps breathlessly from headline to headline, as if there are so many horror stories he only has time to spend a few seconds on each one.

That apocalyptic mood was no longer the stuff of fantasy in 1974, when tuning into any news station could bring you reports of unthinkable violence in Vietnam, Cambodia, Ireland, and maybe right outside your door. The president of the United States was forced to resign in shame, shattering whatever faith most Americans still had in their government, and even cynics discovered Washington was worse than they'd imagined. And since then, the world has never seemed to stop ending, making "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" endlessly relevant.

Writer/director Avishai Weinberger sums it up on Twitter, writing, "To me, the real overarching promise of the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre is the idea that America is f*****g vast, with so much hidden horror beneath the surface, and if you look under the wrong rock, you will find a nest of spiders. ... We only know about these [killers] because we stumbled into their home. Imagine the homes we haven't stumbled into."

Pam's horoscopes all come true

Pam tries to lighten the mood after a near-death experience with a freakish hitchhiker by reading her vanmates' horoscopes. What she finds has the opposite effect. Most horoscopes are famously vague enough to apply to anybody but not Franklin's. "Travel in the country, long-range plans, and upsetting persons around you could make this a disturbing and unpredictable day," Pam reads. "The events in the world are not doing much either to cheer one up." The only inaccuracy is the part about "long-range plans" since Franklin doesn't live long enough to make any. Sally's, meanwhile, sounds like an outright threat: "There are moments when we cannot believe that what's happening is really true. Pinch yourself, and you may find that it is."

Pam goes on to explain the influence of Saturn, a "malefic" planet that's doubly evil because it's currently in retrograde. (In fact, Salon reports reports the working title for the film was "Saturn in Retrograde.") At first glance, the gritty, everyday realism of "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" might seem miles away from the cosmic horror of something like "It" or the stories of H.P. Lovecraft. But as Christopher Sharrett argues in "The Idea of the Apocalypse in 'The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,'" this scene suggests that there's a much bigger evil at work than a hick with a chainsaw. So do the opening credits, which at first seems like an extreme closeup on the hide of the cows the Sawyer family used to slaughter but turns out to be solar flares.

The 'good guys' are pretty awful to Franklin

Even before he gets a chainsaw to the face, Franklin Hardesty is having a pretty bad day. Confined to a wheelchair, he gets knocked over by a truck and sent rolling into a ditch almost as soon as we meet him. His "friends" aren't much better. They mock him mercilessly — Pam's boyfriend, Kirk, even says he's crazier than the Hitchhiker, and if you know the Hitchhiker, you know that's cold. And you can forget about them making accommodations for him. When the crew gets to the old Hardesty homestead, they seem to forget all about him, and poor Franklin has to muscle his way uphill in his wheelchair. And then before he can catch up with the other kids, he finds out they've gone upstairs.

Now, we're not saying the rest of the crew deserve to be chainsawed to death for the way they treat Franklin. For one thing, he seems exhausting for reasons that have nothing to do with his disability. His constant whining is almost unbearable just for the hour he's on-screen, let alone for an entire day in a stuffy van. You can tell he's getting on Sally's last nerve when he begs and begs her to take him with her to the creek to look for Sally's missing boyfriend, Jerry. And then Franklin follows her anyway after she repeatedly tells him not to. We're not saying he deserves to get sliced in two immediately afterward either, but there's certainly a direct line of cause and effect there.

Leatherface endures as much suffering as he dishes out

When it comes to being picked on by friends and family, Leatherface might have a lot to talk about with Franklin, if he hadn't sliced him open first.

Actor Gunnar Hansen has said (via Vulture) he spent time with disabled people to study for his part as the masked killer, and it shows in his nervous, uncoordinated performance. He is, just like we learned about snakes and spiders, more scared of you than you are of him. Just watch how he panics after he meets and murders Jerry. Leatherface's family life can't be helping his mental health either. Almost all of his interactions with Pa and the Hitchhiker involve some kind of verbal or physical abuse — as soon as Pa sees that Leatherface sawed the front door open, he starts yelling at him and beating him over the back of the head.

It's a long-running tradition to give horror fans monsters that are as sympathetic as they are repellent, and Leatherface's mask, with its big black stitches, connects him to Frankenstein, the original tragic monster. Maybe that, more than the need to leave the door open for sequels, is why Hooper can't bear to kill Leatherface in the end, sparing him the grisly fate that meets his brother under the wheels of a truck. Not that the film's treatment of disability is that much more sensitive than Pa's — sometimes it portrays Leatherface as downright subhuman, especially since he mostly communicates with farm animal sounds like pig squeals and chicken clucks.

If you or someone you know is dealing with domestic abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre mixes real and staged footage

Cheapie horror flicks — B-movies — were already big business before Tobe Hooper ever picked up a camera. But those predecessors were hampered by their budgets with their zipper-wearing monsters and cardboard graveyards, while the limitations of "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre" only enhanced it.

Like most of his contemporaries, Hooper couldn't afford to stage everything for the camera (except the murders, thankfully). As Christopher Sharrett points out in "The Idea of the Apocalypse in 'The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,'" Hollywood film could afford to fabricate a dead armadillo, hire trained cows for the scene of the kids driving by the slaughterhouse, or rope off the road and hire their own staff to drive up and down the highway. But any one of those things could have doubled Hooper's budget. So we have a strange hybrid film of staged action in the foreground and documentary footage in the background. A Hollywood film would build a new house and then do what they could to make it look old and crumbling. "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" just parks the camera in an abandoned house — twice the believability for a fraction of the price.

The opening crawl presents this as a true story, and despite all the improbable things that happen, these documentary elements make it easy to believe. You could say the same about cinematographer Daniel Pearl's grainy 16mm camerawork, a medium linked in contemporary audiences' minds with documentaries and news reports. Pearl and Hooper lean into that documentary-style filmmaking style, often showing the action from far away, at one point mostly obscured by grass, as if they had their characters on candid camera.

The kids are unwilling cannibals

The central horror of "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" isn't death but what happens to your body after death. It's there from the very first shot of the decomposing corpses posed like dolls. It's there in the ways Leatherface's family fill their home with mutilated bodies, mixing human and animal remains without distinction. And most of all, it's in the threat of cannibalism.

When Sally thinks she's escaped to safety in Pa's barbecue stand and sees a shape suspiciously like a human torso in the red light of the fireplace, the Hitchhiker confirms the awful truth when he spits at Pa, "Me and Leatherface do all the work. ... You ain't nothing but the cook!"

That horror gets even worse if you're paying attention. Earlier in the film, when they can't find any gas at Pa's service station, the kids decide they might as well get a meal, including a nasty-looking fritter Franklin lets hang out of his mouth like a burned-out cigar. Knowing what we know about Pa's business, it seems the hapless kids — and who knows how many other travelers over the years — have become unwilling participants in Pa's cannibalism. Not that they survive long enough to live with the guilt — except for Sally, and she has too much else on her mind to worry about that.

There's less gore than you may remember

As he was selling "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" to distributors, Hooper had what The Dissolve's Noel Murray calls "some pie-in-the-sky idea that he could get a PG rating for the movie." Granted, PG could stretch a lot farther then than it does now — just look at the full-frontal nudity in "Airplane!" or contemporary PG-rated horror flicks like "Jaws," "Piranha," and even the psychosexual madness of "The Baby" — but not quite that far.

The thing is, if you're watching closely, Hooper's pipe dream makes a lot more sense. A lot of nasty things happen to Sally and company, but we never actually see them. We see Pam and a meat hook and Pam on the meat hook with blood spattered on the wall behind her, but we never see the metal penetrate the flesh. Franklin's death takes place in pitch darkness, and Kirk's barely visible in the distant background of the dimly lit house — but seeing him twitch in his death throes is far more horrifying than any amount of gore could ever be.

The truth is, Hooper did too good a job for his own good. He juxtaposes these gore-free images so well that generations of audiences thought they saw the gnarliest violence imaginable, and it's hard to shake that impression no matter how much you pore over the individual frames looking for blood that just isn't there.

The kills are some of the quickest in horror

"The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" has some advantages as a godfather of the slasher subgenre. It's easy to break the rules before they've been written. Decades of slashers have led us to expect murder to be a slow process — plenty of ominously scored buildup on the front end and a good long look at every detail of the victim's death on the back end. Done well, the formula can keep tension high for minutes at a time. Done badly, it turns a shock into a foregone conclusion. Either way, releasing all that tension is a kind of relief. And Tobe Hooper has no interest in offering relief.

When Leatherface comes for the heroes, he comes out of nowhere. In the first kill, we're already in the disturbing environment of his red room when he pops into frame like a jack in the box and whacks Kirk across the head with a hammer. The whole process only takes about 10 seconds, and the ending is just as sudden and horrifying as the beginning, as Leatherface slams the metal door shut and Hooper waits until then to play the ominous drone on the soundtrack. Jerry and Franklin don't fare much better, only lasting two and 10 seconds, respectively. All this murderous efficiency primes us for the one time Leatherface and family take the time to play with their food, and Hooper masterfully manages to keep that tension at the same level for over half an hour as the Leatherface family prepare to sacrifice Sally.

The Sawyer home is packed with strange details

The best argument against anyone who tries to dismiss "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" as disposable trash is the incredible artistry that went into designing the nightmare world of Leatherface's cabin. Don't be too harsh, though — half the genius of it is the way Hooper makes it look like it was thrown together by a family of unskilled serial killers. The success of "Massacre" would give Hooper the license to go wild with surreal imagery on bigger-budget films like "Poltergeist," "The Fun House," and "Invaders from Mars." But it's obvious that imagination was there from the beginning, and he didn't need much money to exercise it.

That's especially true in the dinner scene. Leatherface's family — named the Sawyers in 1986's "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2" — seem to have a special interest in lamps. One holds a bulb in its dead hand, another is made of a whole skeleton, and most horrifying of all, the overhead light is made from two faces stitched together. The Sawyers also seem to have a punny sense of humor, strapping Sally to a literal armchair, with still-fresh human arms (taken from her friends?) tied around the arms of the chair. And there's the just plain inexplicable, like the table's centerpiece — a chicken head sitting on a wooden block supported by four chicken legs. More birds hang from the ceiling, stuffed and posed as if in mid-flight. Even the radio announcer is forced to admit the Hitchhiker's corpse sculptures are "a grisly work of art."

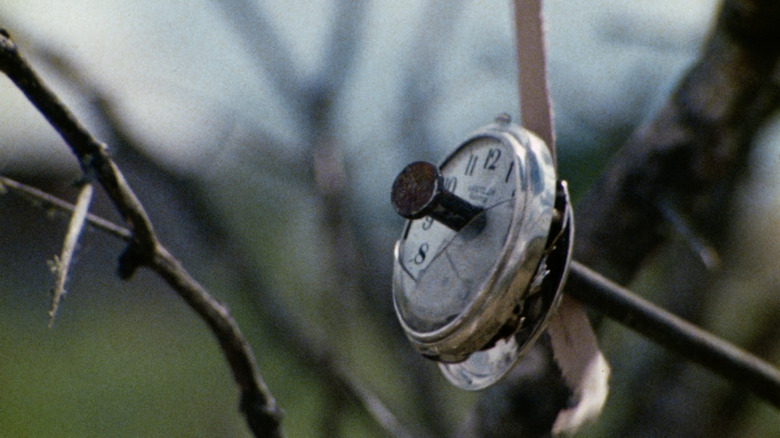

The broken watch shows Pa trying to stop time

One of the strangest pieces of set design lies outside the Sawyer cabin. There's a tree covered in frontier-era dishes, which seems ordinary enough — most likely someone left them out there to dry. But then there's one strange object hanging from another branch — a pocketwatch with a great big nail hammered through it. In "The Idea of the Apocalypse in 'The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,'" author Christopher Sharrett is especially interested in this object, interpreting it as the Sawyers' attempt to stop time. He makes a compelling case for the killer clan as a monstrously distorted version of what Nixon called the Silent Majority — the white, rural Americans who saw the rapid social changes of the '60s and '70s and wanted nothing to do with them. Then as now, Silent Majority types worry their way of life is disappearing, and that's certainly been the case for the Sawyers now that the slaughterhouse no longer needs their mallet-swinging skills.

Symbolically stopping time isn't enough. The Sawyers try to take the new generation off the table by force — something the prologue makes sure to underline, saying their victims' deaths are "all the more tragic in that they were young." More specifically, they're avatars of the youth movements the older generation resented so much, driving around in a VW bus that had been the emblem of hippies "discovering America" for the past decade, studying astrology, and decked out in flower-child fashion like Jerry and Pam's floral-pattern tops, Jerry's octagonal glasses, Sally's braless tank top, and long hair all down the line.

The killings are a proxy war between the patriarchs of the Sawyer and Hardesty families

The killings in "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" are horrifying in large part because they're so random. There's no poetic justice here, just some kids who happened to wander into the wrong house. But if you scratch beneath the surface, you can find a deeper reason behind the carnage that only increases the terror and shows Hooper had more on his mind than just scaring teenagers.

The kids' road trip takes them far into the outer reaches of civilization, down unpaved backroads to a place where there's no sign of human life except a rusted-over service station and a couple falling-down old houses. They could be entering the pre-civilized past or a post-apocalyptic future. As author Christopher Sharrett suggests, that means an older world of blood feuds and wars between clans.

But what would Leatherface's clan have to do with these random kids? Franklin unknowingly explains on the drive over — Grandpa Hardesty used to be a big cattle rancher who hired men to slaughter his herds with a sledgehammer before replacing it with a more high-tech, humane bolt gun. The Hitchhiker insists the old way was better, but he's not an objective source since the new technology cost him his job. The same thing seems to have happened to Grandpa, who the Hitcher insists used to be the best hammer-swinger at the ranch. With Grandpa Hardesty long dead and buried, the Sawyers can only visit the sins of the grandfather on the children — and if their friends get in the way, that's just too bad.

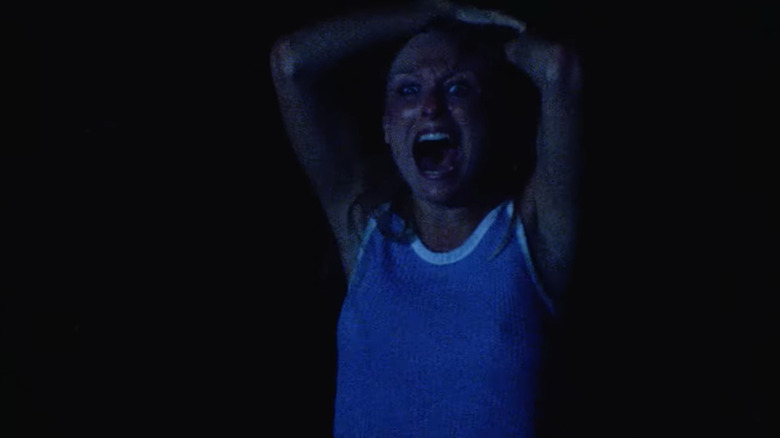

The Sawyers' obsession with tradition saves Sally's life

Author Christopher Sharrett points out the many ritualistic aspects of the Sawyer family's lifestyle, describing Sally's murder as a human sacrifice and even their cannibalism as an echo of the ritual cannibalism some cultures have enacted to commune with the spirit of their victims. But more importantly, all these rituals are stripped of meaning — in this modern, materialistic world, cannibalism is no longer a religious observance. It's just a way to make money from tourists.

However you interpret it, the Hitchhiker's insistence on letting Grandpa make the final blow has clear ritual implications. There's a long tradition of ritual duties falling on the patriarch, all the way up to modern duties of blessing the meal or being the first to carve the Thanksgiving turkey.

In this case, of course, the patriarch's so old and frail he can't even hold the hammer he's supposed to kill Sally with. This gives Sally the opening to make a break for it and eventually escape. The model for all future final girls, her last scene, manically laugh-crying and covered in blood, suggests she's gotten out with her life, if not necessarily her sanity. To answer the question posed by the film's poster, she survived ... but what is left of her? After such a shattering movie experience, you could ask the same question of the audience.