American Psycho Ending Explained

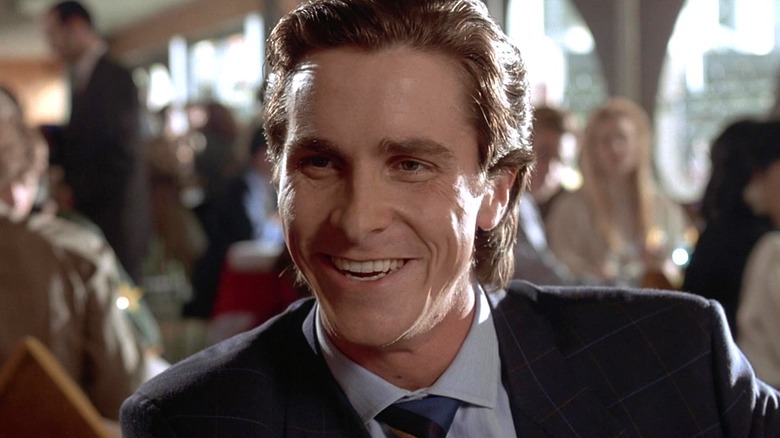

The film adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis novel "American Psycho" debuted in 2000, and it was quickly cemented as having one of the most ambiguous and confusing endings in cinematic history. While initially appearing straightforward, the movie intentionally unravels in the last act, making plenty of people wonder whether or not Patrick Bateman's murders even took place. Did Bateman really kill Paul Allen, or did his rival move to London? What's the deal with Allen's apartment, and why does Bateman's lawyer mistake him for someone else? Is Christian Bale's character actually the serial killer he claims to be? Was this all just in his head?

While it's almost impossible to come up with a definitive answer to the infinite questions posed at the end of this thrilling film, analyzing its themes, dissecting its characterization, and examining the director's statements can help unravel the truth of Bateman's muddled mind. Whether this movie depicts a deeply troubled man working at a New York City investment firm or puts a homicidal spin on the term "Wolf of Wall Street," this is everything you need to know about "American Psycho's" confusing conclusion.

First thing's first: Bateman has a personality disorder

Before we can talk about the ending of "American Psycho," we need to get one thing straight: The term psychopath isn't a clinical diagnosis. However, people like to throw the word at anyone who deviates from social, ethical, and neurotypical norms. The proper DSM-IV classification for Patrick Bateman is antisocial personality disorder, but that doesn't sound as punchy as "American Psycho," hence the chosen title.

Still, no matter which way you spin it, whether Bateman is a killer or the audience is only watching his delusions play out on-screen, there's no question that Bateman is suffering from a very real disorder. Between his manipulation of the people around him, frequent lying, lack of empathy, boundless rage, complete absence of guilt, and severe disregard for the safety of himself and others, Bateman's thoughts and (possible) actions display symptoms of the disorder in spades. The real question is whether or not he acts on his homicidal impulses outside of his head.

Real or fabricated? Dissecting the fog

We first witness Bateman's disordered traits in the film's second scene, in which Bateman insults a bartender and tells her that he wants to stab her. Perhaps she doesn't hear him over the music, or maybe Bateman only fantasizes about saying this. Regardless, the aggression, mood shift, and disarming wink that ends the episode are the first jarring clues that Bateman isn't as polished as he seems. Nobody likes waiting to be served, but thinking about playing with the bartender's blood because her club doesn't accept credit cards isn't exactly healthy.

Bateman displays this contradictory verbal behavior throughout the film, with bizarre statements that may or may not be said out loud. He tells a model that he works mostly in "murders and executions," as opposed to "mergers and acquisitions," and she doesn't bat an eye. He also admits to his unfazed fiancée that his "need to engage in homicidal behavior on a massive scale cannot be corrected, but [he] has no other way to fulfill [his] needs" while drawing a picture of the woman he just killed with a chainsaw.

One thing's clear, regardless: Bateman has a personality disorder, and he doesn't really try to hide it. While having antisocial personality disorder doesn't make someone violent or "evil," Bateman doesn't try to reign in his darker tendencies. People get hurt, and he shows little to no remorse.

But did he actually kill people?

One of the more popular interpretations of "American Psycho" suggests Patrick Bateman never actually killed anyone, and the murderous actions we see played out merely take place in his unhealthy mind. Now, while there's no way to be 100% certain that Bateman did murder people, there's a lot of evidence supporting the idea that he is, in fact, a serial killer.

One evening early on in the film, Bateman encounters a random woman waiting to cross the road and proceeds to creepily walk alongside her. In the very next scene, we see Bateman aggressively arguing with some non-English-speaking dry cleaners about not bleaching what appear to be bloody sheets. He aggressively loses his cool and even threatens to kill the dry cleaner. When an acquaintance unexpectedly comes in and inquires about the stains, Bateman nervously claims they're "cranberry... cran-apple," but they sure look bloody. The obviously frazzled Bateman probably killed someone the night before — likely the random woman on the street from the previous scene.

Even less open for debate is the first time we actually witness Bateman kill somebody. After asking a homeless man why he doesn't get a job and taunting him relentlessly, Bateman straight up stabs him in the chest before kicking his dog to death. Compared to various other murder scenes which come later, this one stands out as firmly grounded in reality, with nothing present to indicate that it's merely a sick fantasy.

Patrick has no discernable MO

According to Psychology Today, most serial killers display a pattern in victimology, weapons, and modus operandi. Sometimes, the method is varied when a killer is starting out, but Patrick is truly all over the map. Most of his murders are premeditated, giving him the means to control how the kills go down. Outside of the homeless man, the helpless puppy, and the rampage Bateman goes on after the ATM killing, he seems to have his homicidal agenda laid out. But he doesn't know what he wants, and it shows.

Bateman is into blondes, evidenced by his fiancée, his mistress, his secretary, and the two sex workers he victimizes and later kills. But he also goes after his male coworker and an old friend — both brunettes. Likewise, Bateman toggles between people he knows and disenfranchised strangers. Serial killers often begin their sprees with someone they know in the heat of the moment, but it's rare to go back-and-forth the way Bateman does.

More bizarrely, Bateman's kills are seriously dramatized and employ beatings, an ax, a chainsaw, a nail gun, a real gun, and vivisection. He also admits to partially eating people, which we see play out in one traumatizing scene. While some might argue that he's just figuring out what he likes, these extreme variations in both methodology and victimology often make it seem like his kills are scatterbrained delusions rather than the premeditated acts of a serial killer.

His kill count might be lower than he thinks

While it can be argued that Bateman did actually murder his fair share of sex workers and homeless people, we can't be certain he's killed as many people as we're led to believe. In fact, Bateman doesn't even know how many people he's killed. In a panicked phone call to his lawyer, Bateman says, "I've killed a lot of people. ... I guess I've killed maybe 20 people. Maybe 40!" Jumping from 20 to 40 is quite the leap, which almost assuredly indicates that Bateman has trouble differentiating between his real murders and his fantasy murders.

Perhaps the biggest sign that Bateman's kill count is on the lower end of his own personal spectrum, however, is the fact that there's no cops crawling down his neck. While it's easier to imagine someone like Bateman getting away with murdering random homeless people, sex workers, or women he meets while walking home, it's highly unlikely he's remained off the NYPD's radar with upwards of 40 murders.

Is he even really Patrick Bateman?

Throughout the entirety of the movie, we see Christian Bale's character repeatedly called names other than Patrick Bateman by various individuals — leading some viewers to question whether or not he really even is Patrick Bateman. However, there should be absolutely no doubt that he is truly who he says he is and that any misidentifications by other characters are purely their own mistakes.

In fact, identities are mistaken constantly and in perpetuity. In the opening scene, while Bateman is having dinner with Craig McDermott, Timothy Bryce, and David Van Patten, McDermott asks, "Is that Reed Robinson over there?" "Are you freebasing," Bryce replies. "That's not Reed Robinson." Instead, Bryce corrects him and claims it's Paul Allen. Bateman then steps in and says "It's not Paul Allen. Paul Allen is on the other side of the room over there." The camera then shows us the individual in question, who is most definitely not Paul Allen — who's normally played by the recognizable Jared Leto.

The first time we meet the real Paul Allen, he mistakes Bateman for Marcus Halberstram — a mistake he never corrects. Bateman brushes this off as "logical," telling us, "Marcus also works at P&P and, in fact, does the same exact thing that I do. He also has a penchant for Valentino suits and Oliver People's glasses. Marcus and I even go to the same barber." In the same scene, Allen also calls McDermott "Baxter," indicating misidentifications are not isolated instances.

Does Bateman really have an alibi?

The biggest mystery in the film revolves around whether or not Patrick Bateman actually killed Paul Allen. And though we witness Bateman kill Paul Allen "with an axe in the face" and hear him claim that the body is "dissolving in a bathtub in Hell's Kitchen," we're presented with some evidence to support that idea that Allen is actually alive and well ... but we shouldn't believe it.

The first piece of evidence is when, while having dinner with the private detective investigating Paul Allen's disappearance, Bateman is surprisingly given an alibi for the night of Allen's disappearance. According to Detective Kimball, Allen was verified to have had dinner with Marcus Halberstram — i.e., the colleague Allen had unknowingly mistaken Bateman for the entire time. The real Halberstram, unsurprisingly, claimed he was not having dinner with Allen. Rather, he claimed he was having dinner with other colleagues ... including Patrick Bateman.

While it's easy to conclude that Bateman forgot about this dinner, blacked out, or simply imagined killing Paul Allen, it's far more likely that Bateman was actually not at said dinner. We already know mistaken identities are commonplace among the Pierce & Pierce elite, and the film never introduces us to any of the colleagues Bateman supposedly dined with. Thus, it's extremely likely that the real Halberstram simply mistook a different colleague for Bateman — as did Paul Allen — thus providing Allen's murderer with one ultra lucky alibi.

The secretary situation

Bateman's secretary Jean almost becomes his victim when he charms her into coming home with him. Jean is the only woman in the film that Patrick shows any level of regard for, but that's not saying much: His hankering to kill her is still strong enough to make him grab his nail gun and almost kill her.

However, after Patrick's mental breakdown at the ATM and subsequent murder spree, he tells his lawyer that he did kill one of his exes with a nail gun. He rambles, "I killed Bethany, my old girlfriend, with a nail gun." Who is Bethany? We never see her, nor is she mentioned previously. He could be talking about a real person from before the film's events, but it does seem like Bateman and Jean have a messy romantic history. He treads lightly when mentioning his fiancée, for example — and this is not a guy that generally cares about people's feelings.

Bateman could have easily invented an alternate version of Jean in his head and imagined killing her. He calls her during one of his least lucid moments, so he definitely knows, on some level, that Jean is alive. But these contradictions offer more food for thought that Bateman has imagined all (or some) of his kills, as he doesn't have a habit of repeating murder weapons. Whether he hallucinated the whole thing or developed an affinity for the nail gun is up to the audience.

What's the deal with Paul Allen's apartment?

One of the most confusing moments in the film takes place when Bateman shockingly finds Paul Allen's apartment — previously full of dead bodies — spotlessly clean and being shown to potential tenants. But don't be fooled by this clever twist! The apartment really was full of dead bodies, and Paul Allen was definitely living there before he was murdered.

With a lovely view of Central Park, Allen's apartment is known to be one of the most expensive properties in New York City. Thus, the owners understandably want to get someone living there and paying rent there as soon as possible. Rather than call the police upon discovering the closets full of bodies, which would devalue the property value, the owners quietly have the mess taken care of — hence why the apartment has been given more than just a new coat of paint.

The evidence comes when Bateman has a strange but serious interaction with the real estate agent — who instantly drops her facade when Bateman admits he is not her 2 o'clock appointment. She asks Bateman whether or not he "saw the ad in the Times" before informing him that there "was no ad in the Times" — a strangely investigative question. Putting two and two together, she calmly but sternly tells the confused (and lucky) Bateman that she thinks he should leave, not make any trouble, and never come back. Naturally, he agrees.

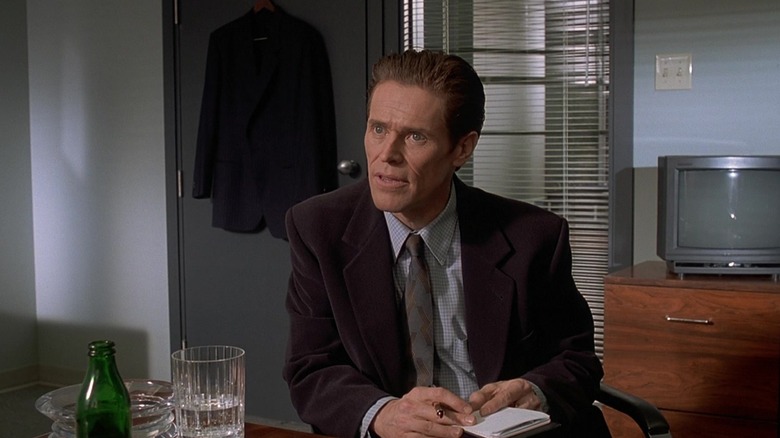

Don't let the lawyer fool you

Played by Stephen Bogaert, Patrick Bateman's lawyer has been responsible for most of the confusion surrounding the ending the "American Psycho" — but don't let him fool you! Harold Carnes knows far less about what's going on than you might think.

First and foremost, Carnes doesn't even know who Patrick Bateman is, mistaking him instead for "Davis," and asking him if he's still dating "Cynthia" — two characters we've never met. When pressed, he says, "Davis, I'm not one to badmouth anyone. Your joke was amusing. But c'mon man, you had one fatal flaw. Bateman is such a dork — such a boring, spineless lightweight." This misidentification of Bateman immediately makes anything that comes out of Carnes mouth invalid, as he can't even be tasked with keeping his own clients straight. Even after Bateman states very clearly that he is, in fact, Patrick Bateman, and that he chopped Allen's head off and "liked it," a disturbed Carnes dismisses it as impossible, saying, "I had dinner with Paul Allen twice in London just 10 days ago." But did he really?

Probably not. After all, how can we believe Carnes when he already mistook Bateman, his own client, whom he speaks to on the phone "all the time," for someone else? We also already know from Detective Kimball that Allen was mistakenly identified in London by another individual, meaning the confused Carnes probably dined with someone else entirely.

The director's take

Viewers of "American Psycho" can argue forever over whether or not all of the film's violence only takes place in Bateman's head. However, the director herself argues against this and takes the blame for misleading audiences.

In a group discussion of the film with journalist Charlie Rose, lead actor Christian Bale, and the novel's writer Bret Easton Ellis, director Mary Harron admitted that she failed with "American Psycho's" final scene. "One thing I think is a failure on my part," she explained, "is everyone keeps coming out of the film thinking that it's all a dream, and I never intended that. ... I think it's a failing of mine in the final scene that I just got the emphasis wrong because I should have left it more open ended. ... It makes it look like it was all in his head, and as far as I'm concerned, it's not."

The main problem with the final scene is the aforementioned Carnes, who can't keep his clients straight. After misidentifying Bateman as "Davis" and claiming to have had dinner in London with Paul Allen, viewers are tricked into thinking that Bateman can't separate fantasy from reality. In truth, it's Carnes and the rest who are confused, and it's Bateman — who exhibits the most meticulous attention to detail — who simply can't have his confession taken seriously.

Things that can't be real

Even if Bateman really is a killer and the action does not merely take place inside his sick and twisted mind, that doesn't mean everything we see play out actually happened.

The story's primary plot arc follows Patrick Bateman's mentality from psychopathy to full-blown psychosis. The film's screenwriter, Guinevere Turner, told Yahoo Movies, "Everything was really happening. But at some point, we're starting to see things through Patrick's eyes. He's losing his mind." Turner mentions "the scene where he gets the two hookers to come over, and he's videotaping himself and looking at himself in the mirror" as one of the turning points in the film. She states that the event really took place but "in real life, they probably weren't as attractive as they are, and it wasn't all as Penthouse Letters as it is."

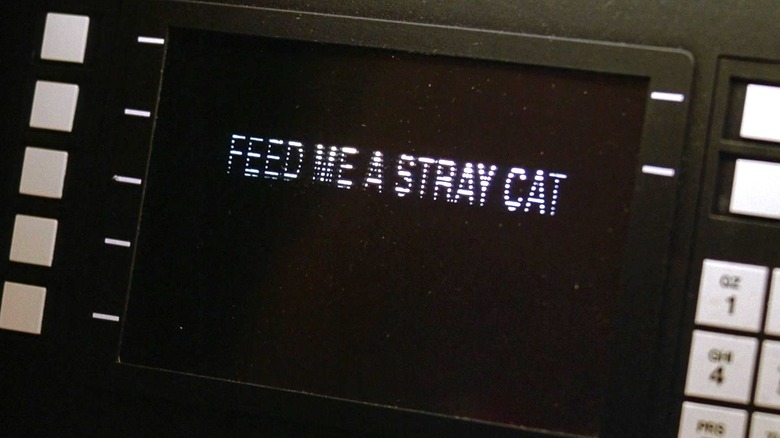

Of course, the moment we realize that something is truly astray with the reality being portrayed on screen is when the ATM instructs Bateman to feed it a stray cat. "He's there," Turner says, "he's got the kitten, but the ATM doesn't actually say that. He's just going nuts." His deteriorating mentality is further on display when, after firing his handgun at some police officers, their cars explode in a fiery blaze. Bateman himself even questions whether or not that's even possible, looking at his gun with confusion. Thus, it's highly probable that his epic rampage wasn't quite so epic — if it even happened at all.

Copycat syndrome drives the film

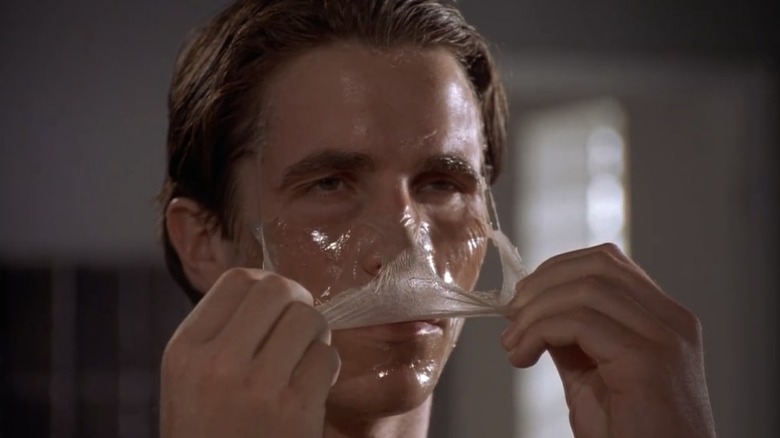

Patrick Bateman wore a face mask before it was cool. But along with their hydrating factors, he uses products to fake his humanity. His face masks parallel the real mask he wears daily, but as he begins to realize as the film goes on, no amount of hair products and lotion can fill the void he has inside.

The Pierce & Pierce men's infatuation with trying to look the same causes the movie's many instances of mistaken identity, ultimately leading to Bateman getting away with murder. Everyone at the company goes to painstaking lengths to mirror each other's looks, all wanting what they can't have, whether it's someone else's haircut, their girl, or even something as trivial as business cards. The ridiculous lengths each character goes to, in order to become a carbon copy highlights the superficial consumerism that the film dramatically critiques. While some serial killers copycat another killer's MO that they have a creepy fascination with, Bateman turns the tables, using his coworker's own copycat tendencies to get away with murder.

It's all a critique of '80s male hedonism

Much like the book it's based on, "American Psycho" isn't really about Patrick Bateman. Rather, the film aims to portray the self-indulgent and hedonistic Wall Street elite of 1980s New York in a negative light.

The whole reason Bateman gets away with the murder of Paul Allen is because Allen, like others in the company, doesn't even know who he is. Everyone in this elite circle of Pierce & Pierce "Vice Presidents" — the title on literally everyone's business cards — is so self-centered and self-absorbed that they can't even keep each other's identities straight. Their attention is firmly focused on acquiring material wealth, lording it over others, and snorting cocaine in club bathrooms. Their biggest problems revolve around getting dinner reservations at Dorsia. Even the owners of Allen's apartment are willing to dispose of a serial killer's evidence to ensure maximum profit.

In a group discussion with Charlie Rose, "American Psycho's" author, Brett Easton Ellis, admitted that the book is primarily a critique of male behavior — something director Mary Harron recognized from the get go. One of the best things about "American Psycho" is how it can be analyzed as a positive example of what can happen when the "female gaze" is cast on male vanity and, in this case, male violence. All of the central characters are male, and many of Bateman's victims are female. Most importantly, there are absolutely no redeeming qualities about Bateman. In fact, there are no redeeming qualities about any man in the entire film.

The original ending had a musical number

If you think "American Psycho's" ending is bizarre, wait till you hear about the original conclusion. David Cronenberg occupied the director's chair before Mary Harron, but instead of hiring a scriptwriter, he asked Bret Easton Ellis to write the screenplay. The catch? Cronenberg forbade Ellis from writing scenes set in restaurants or clubs. Apparently, even with a heavy dose of homicide, those settings are too boring.

Ellis decided to invent a bunch of new scenes. The most baffling was the intended ending — a musical number atop the World Trade Center. A musical scene definitely would have lent itself to the theory that the murders are all in Patrick's head, but it also might have confused the audience further. Moreover, that already dicey concept would not have aged well. The film came out just one year prior to the September 11 attacks, and the scene may very well have prevented "American Psycho" from becoming the cult classic it is today. While it's probably best that the musical number stayed on the cutting room floor, fans itching to see Bateman burst into song do have an outlet — Duncan Shiek turned the story into a Broadway musical. And yes, there are videos.