That's What's Up: The Most Successful Dark And Gritty Reboots In Comics

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: What are the most successful "darker and grittier" reboots? — @YellFeat

Despite the fact that it seemed to be the dominant approach to comic book storytelling for about three decades, a grim 'n' gritty reboot is a tricky thing to pull off. At their best, they can add layers of nuance to what often started as a pretty simple story, but for every one that actually pulls it off, there are a dozen that just don't work—and a handful that wind up as just straight up embarrassing. And honestly? That has a lot to do with the motivations behind them.

The worst dark reboots are the ones that stem from the idea that superheroes need to be taken very seriously, and that anything that has even a hint of silliness, comedy, or even happiness is something to be ashamed of. Those are the stories that run counter to the spirit of the genre, and for a lot of readers, make the very idea of a darker take something to be suspicious of. But that doesn't mean that they can't make for some pretty great stories when they're done right.

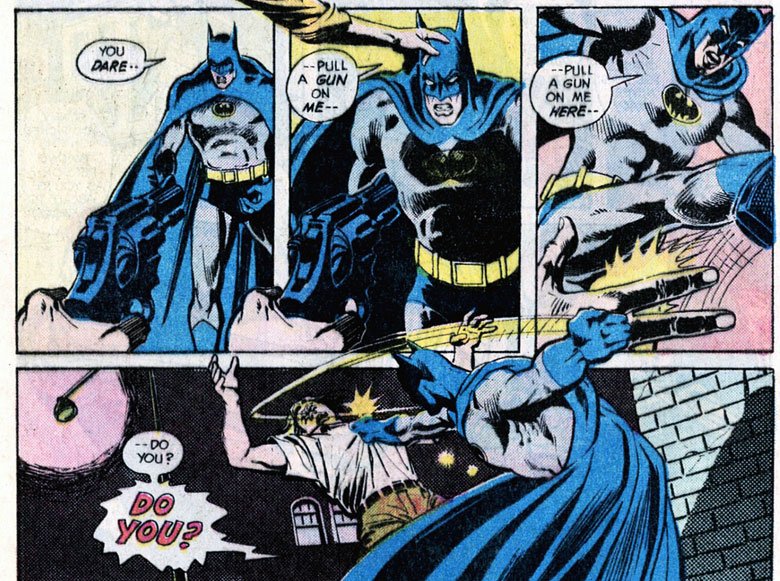

The darker Batman of the 1970s

Honestly, it's easy to argue that the most successful dark reboot of all time is the one that Batman went through in the early '70s.

It's actually one of the more interesting pieces of the Dark Knight's long and frequently bizarre history. The Batman TV show made the character a household name in the '60s, but it did it by taking a campy and frequently very silly approach to the source material. Despite the overwhelming success of the show, there was a segment of fandom that took issue with that. As Bat-historian Glen Weldon wrote in his truly indispensable The Caped Crusade—which, in the interest of full disclosure, I was interviewed for in my capacity as the World's Foremost Batmanologist—there was a reaction that played out in the pages of fanzines like Billjo White's Batmania that went from excitement at the idea of seeing sound effects pop up onscreen to a slow-motion trainwreck of fans getting downright irate about what they saw as a disrespect to the source material, insisting "that's not my Batman!"

The thing is, it was their Batman. Producer Lorenzo Semple Jr. may have outright stated that the entire gag of the show was that it was a "classy comedy" full of "dead-pan satire" that worked because it was treating goofy material with deadly seriousness, but the bulk of that first season was pretty strictly adapted from the comics. If you go back through those issues and match them up with their source material, you can pretty easily see that Semple and the other producers weren't even digging through the archives for inspiration—they were just grabbing stuff off the newsstand and rewriting it.

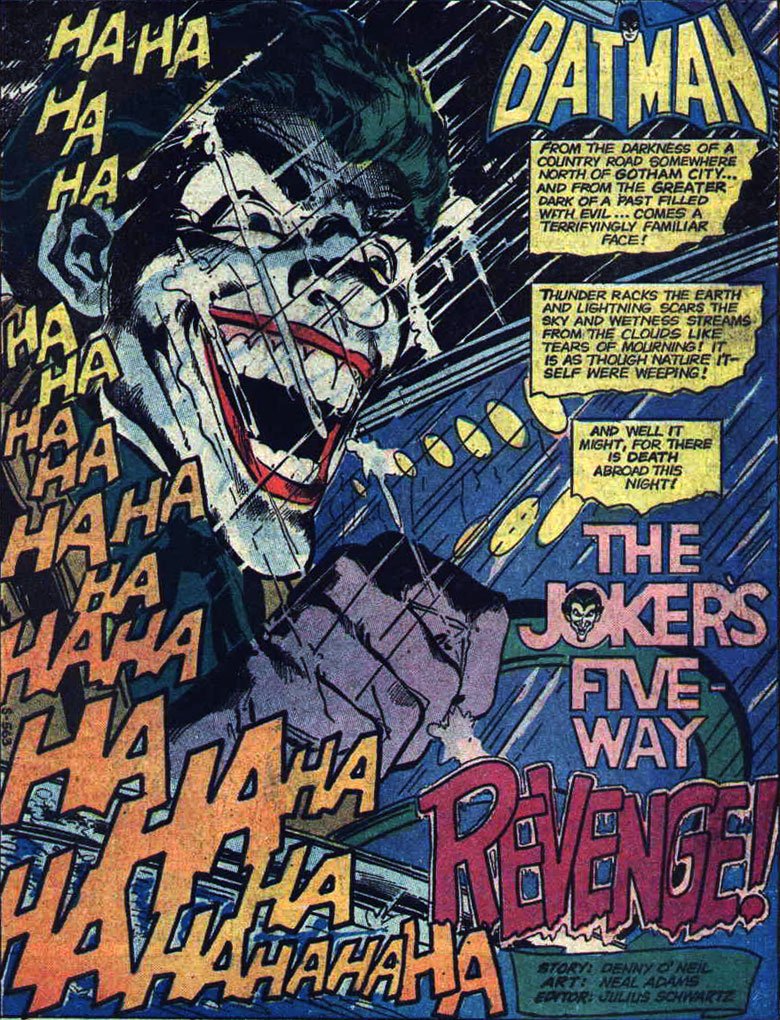

The Joker's Five-Way Revenge

After Batman went off the air, there was an almost instantaneous reaction from creators to take Batman away from campy gimmicks and back to his darker roots. In December of 1969, only eight months after the show's final episode, Batman #217 saw Frank Robbins, Irv Novick, and Dick Giordano ship Robin off to college and move the Caped Crusader out of stately Wayne Manor and into a new headquarters in the heart of Gotham City, immediately distancing themselves from the aesthetics of the show. Batman even says in the comic that the stuff readers might recognize from TV had put them in danger of becoming "outmoded, obsolete dodos of the mod world outside."

This move was followed by stories that took on darker themes, too. Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams produced famous stories like "The Joker's Five-Way Revenge" that emphasized the Joker's murderous nature, and "Daughter of the Demon," whch added new characters and world-traveling adventure. By 1975, Steve Englehart and Marshall Rogers arrived with a year-long run that revived villains like Deadshot and Hugo Strange, who hadn't been seen since the Golden Age, and updated them as deadly foes. This set the tone for everything that came after, with a trend that hit its apex in 1986 and Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli's Batman: Year One, the story that firmly grounded him in a gritty, crime-ridden urban hellscape for the next thirty years.

At the same time, I'm not really sure that counts as a "reboot" the way other stories do. Year One may have provided Batman with a new origin story, but it wasn't that much of a departure from the approach that had already been seen in Batman comics for the past 15 years—and was certainly less of a departure than the other post-Crisis reboots that you got with Superman and Wonder Woman. Instead, it felt like a pendulum swinging the way it has for the past 75 years, from the early Shadow-inspired stories of the Golden Age, to the sci-fi '50s, the gimmicky '60s, the darker '70s and '80s, and on into the over-the-top superhero stories we're seeing today.

It did, however, pave the way for other reboots that took a similar approach, with varying degrees of success.

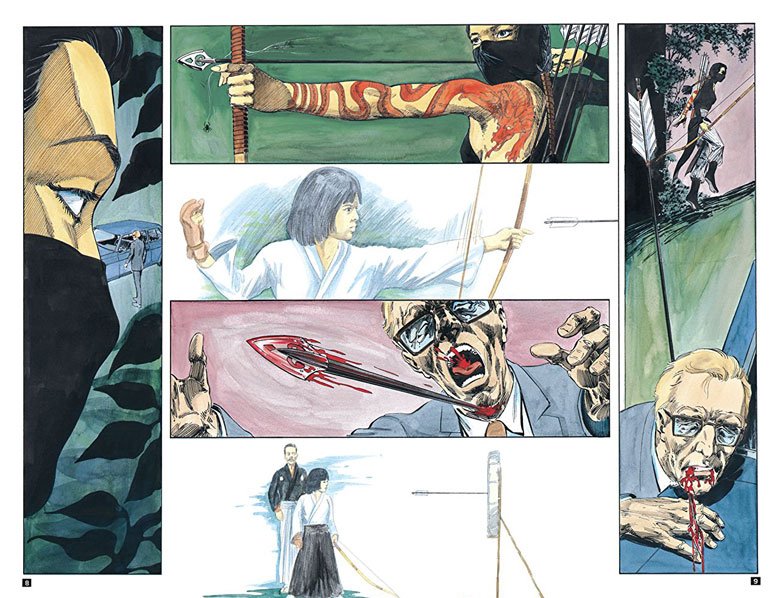

Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters

Believe it or not, one of the most notable dark-and-gritty reboots ever came when Mike Grell revived Green Arrow for The Longbow Hunters in 1989. Of course, that makes sense. Ollie Queen had always been a second-rate Batman, so once DC struck gold with Year One, it was pretty much inevitable that they'd try it with Green Arrow, too.

That's not a dis on Ollie, either, but c'mon. From the '40s to the '60s, that dude drove around in an Arrowcar that he kept in an Arrowcave and fought crime alongside a kid sidekick in a red-and-yellow costume using an endless string of trick arrows. It's not a hard connection to make. With Longbow Hunters, however, Grell swapped out the boxing-glove arrows for broadheads and stories that saw him dealing often lethally with much more violent crimes. At the time, it was a huge success, revitalizing Green Arrow and giving the character an influence that you can even see today in the way that the Arrow TV show approaches its storylines.

That said, I'm not sure it really holds up that well. Longbow Hunters in particular is one of several comics from that era that use sexual violence as a plot point, and the way it slides into brooding, blood-soaked vigilante stories makes it feel like an artifact of its time rather than the bold new direction it was hailed as at the time. In its own way, it's as quaint and hokey as "Hard Traveling Heroes," a historically important story that involves Green Arrow finding out that drugs exist for what appears to be the very first time.

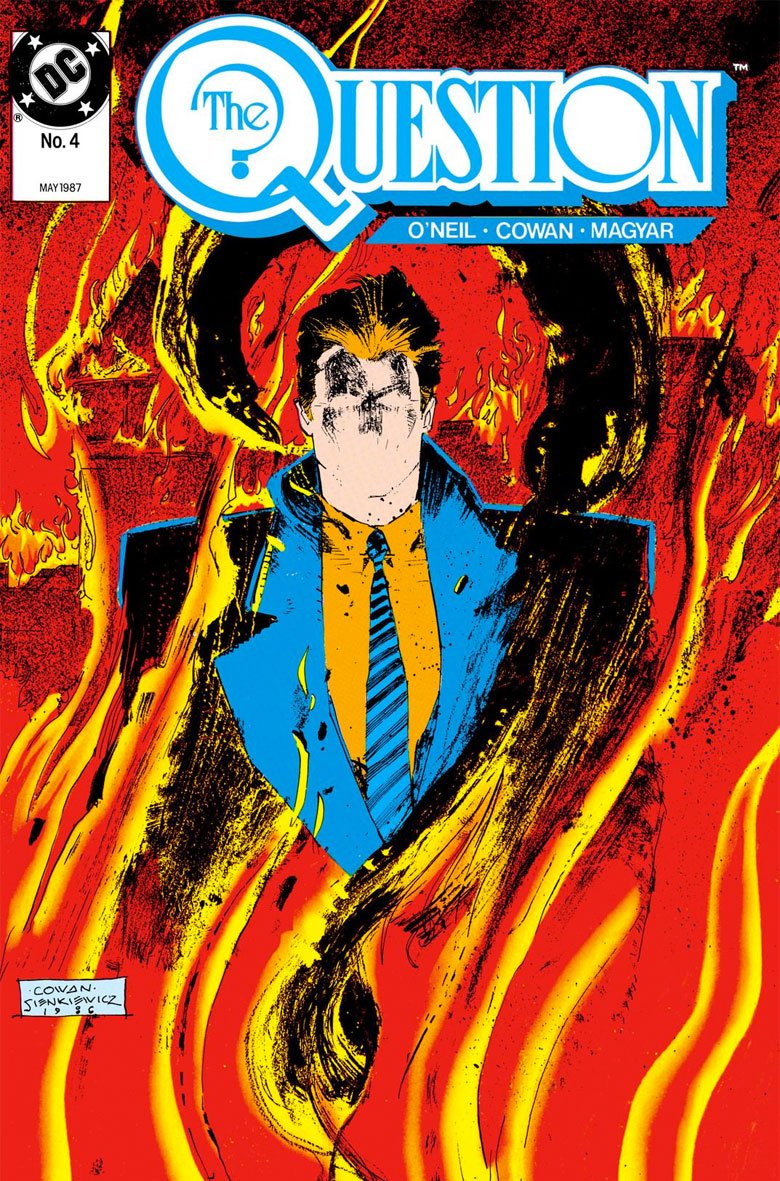

The Question, on the other hand, holds up great.

The Question

The Question was originally created by Steve Ditko at Charlton Comics as one of several characters who were meant to embody Ditko's objectivist philosophies on the comics page. He'd eventually go all in with the downright incomprehensibly Mr. A, but honestly? The original Question stories weren't that far from it, and led pretty directly to inspiring another uncompromising hard-liner: Rorschach from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen.

In 1987, though, Denny O'Neil and Denys Cowan relaunched the Question in the context of the new DC Universe, and ended up with one of the most thoughtful and compelling meditations on heroism and what it means that superhero comics have ever seen. Make no mistake, it's dark in a way that goes beyond just having violent fights or a lot of cusses—it deals with some grim psychology, including suicidal ideation, the lingering effects of violence, and whether it's heroism or folly to continually fight against a world that you know in your heart that you can't really change.

O'Neil even included a suggested reading list in each issue's letter column that primarily featured books on Zen Buddhism, Tai Chi, and Taoism, so that readers would be able to follow along with Vic Sage's own philosophical journey. At the same time, it never reads like a textbook. It's still a superhero comic, full of action and adventure, villains and weird gadgetry, and everything else readers would expect from the genre.

The only thing that I think holds it back from qualifying as one of the best grim 'n' gritty reboots of all time is that it doesn't actually feel like it's that big a departure from the source material as much as it's a natural extension of how that book started. The Question had always been a character who combined superheroics with philosophy, and while O'Neil's influences were about as far from Ayn Rand as you can get, it still worked within that same weird sub-genre of superheroes who liked to spend their time talking a lot about the nature of morality.

It's a great book. But as good as it is, it's nowhere near the best dark reboot. It's in the conversation, sure, but there's a pretty clear heavyweight champion in this fight.

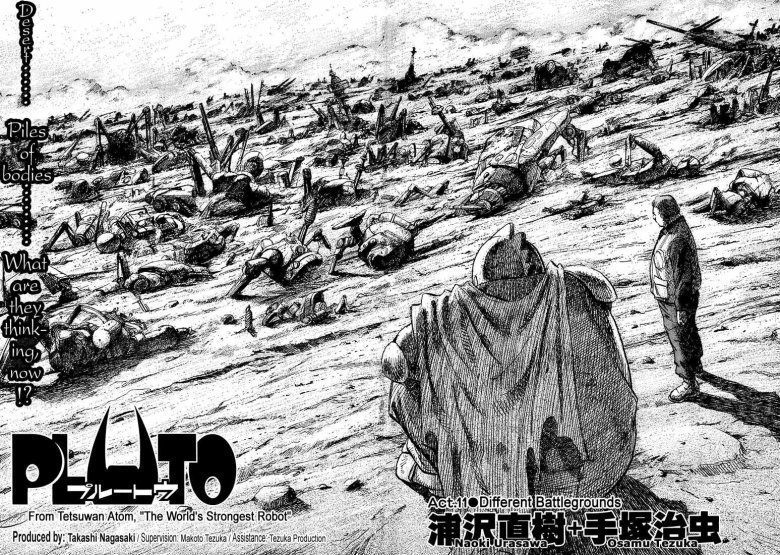

Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka

The best of the bunch—ever—is Naoki Urasawa's Pluto. Nothing else even comes close.

Originally published from 2003 to 2009, Pluto is the definition of a dark and gritty reboot: a retelling of "The Greatest Robot on Earth," probably the best-known and most beloved story from Osamu Tezuka's legendary Astro Boy. The big trick, however, is in the approach. Tezuka's 1964 original is, of course, a rollicking action-adventure story that follows Astro Boy (or Atom, as he's known in Japan) as he tries to stop a hulking, unstoppable villain named Pluto from destroying the seven strongest robots on Earth in an effort to prove his supremacy.

Urasawa's version, on the other hand, was recast as a sinister murder mystery in which Pluto spent the first stretch of the story as an unseen but terrifying villain who left broken heroes in his wake. Rather than focusing on Atom, the story was told through the point of view of the other characters, starting with Gesicht, an android detective tasked by Interpol with investigating the crimes, and shifting around to other characters.

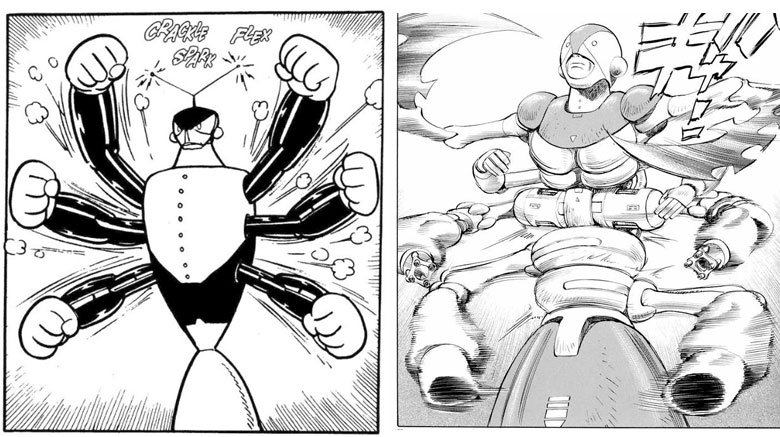

Reading the two stories side by side, you can even see the way Urasawa directly lifted panels from the original, like when the Scottish robot, North #2, prepares for battle by whipping off his cape to reveal his extra arms.

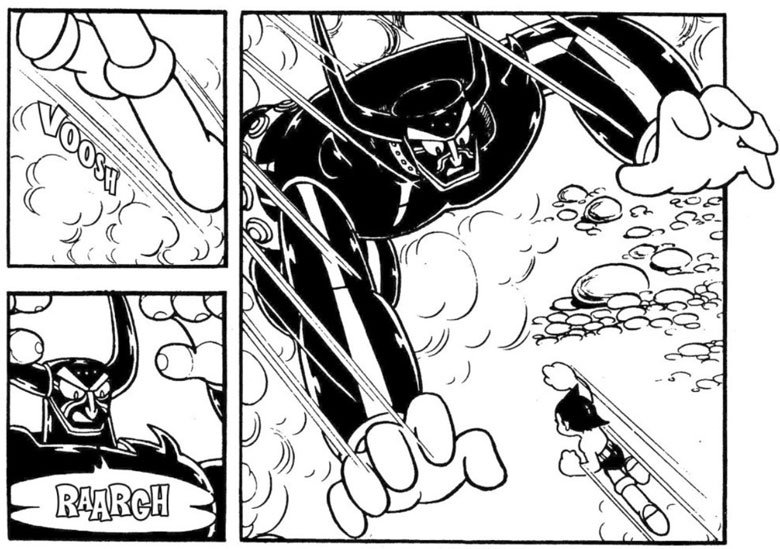

Astro Boy vs. Pluto

But really, that's one of the things that makes it work so well.

"The Greatest Robot on Earth" was cartoony and kid-friendly, with the kind of slapstick gags you'd expect from a story for children—Urasawa, for instance, tends to leave out the part where Atom fights bad guys with a machine gun that comes out of his butt. At the same time, it ends up getting into some pretty heavy stuff. The robots that Pluto destroys are presented as brave, friendly characters that are killed, sometimes in terrifyingly violent ways. Tezuka's version of Gesicht, for instance, is torn in half during his fight, and even though it's gears and springs falling to the ground instead of a shower of blood, it's still pretty intense.

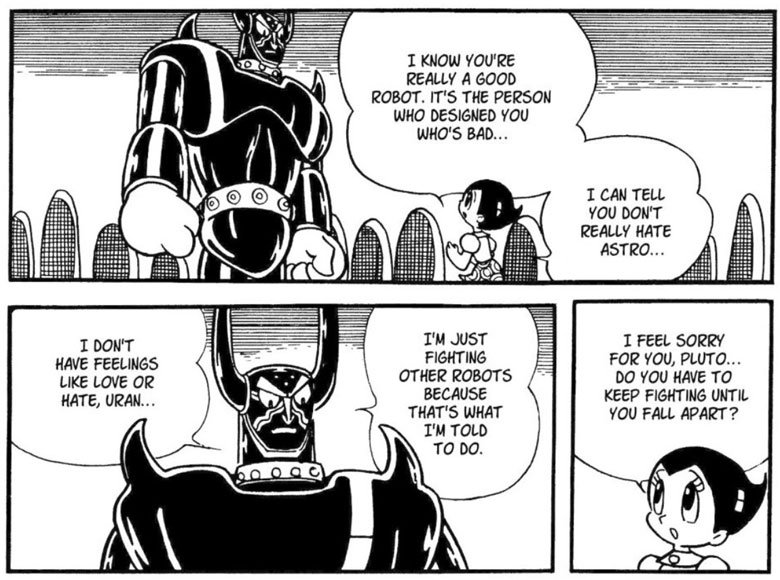

Beyond that, the story frequently deals with ideas of morality. At the end of the day, Pluto is himself just a pawn in someone else's grab for power, and while he claims to not experience emotions in the way that Atom and his sister Uran do, there are huge sections of the story that are devoted to ideas of morality and fairness. When Pluto battles Epsilon, a solar-powered robot who has dedicated his life to taking care of children, there's a section in which Pluto is caught in a landslide at the bottom of the ocean, and Epsilon has to decide whether to rescue his foe or leave him to die. The decision is made when Epsilon realizes that kindness and mercy, even to one's enemies, are a better example to set for his children, even if he's going to have to face that same enemy again at the risk of his own life.

Astro Boy: The Greatest Robot on Earth

Those aren't just the elements that made Tezuka's story one of the genuine masterpieces of shonen manga, they're the foundation on which Urasawa was building a much darker story.

By shifting the focus of the story away from Atom, Urasawa is allowed to expand on the world in which the story takes place, taking a different direction that uses the deaths of robots for more than just the opening act of a battle between Pluto and Atom. He weaves in themes of racism, introducing a militant anti-robot group and diving into the inherent tragedy of Atom's creation, and threads the events of the story through a plot that draws heavily on the events of the Iraq War. But that's just on the macro scale.

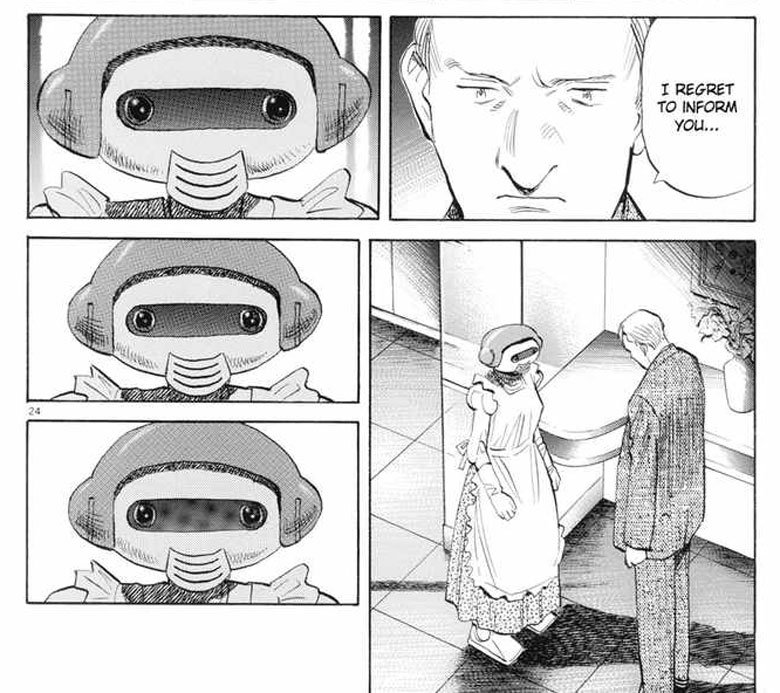

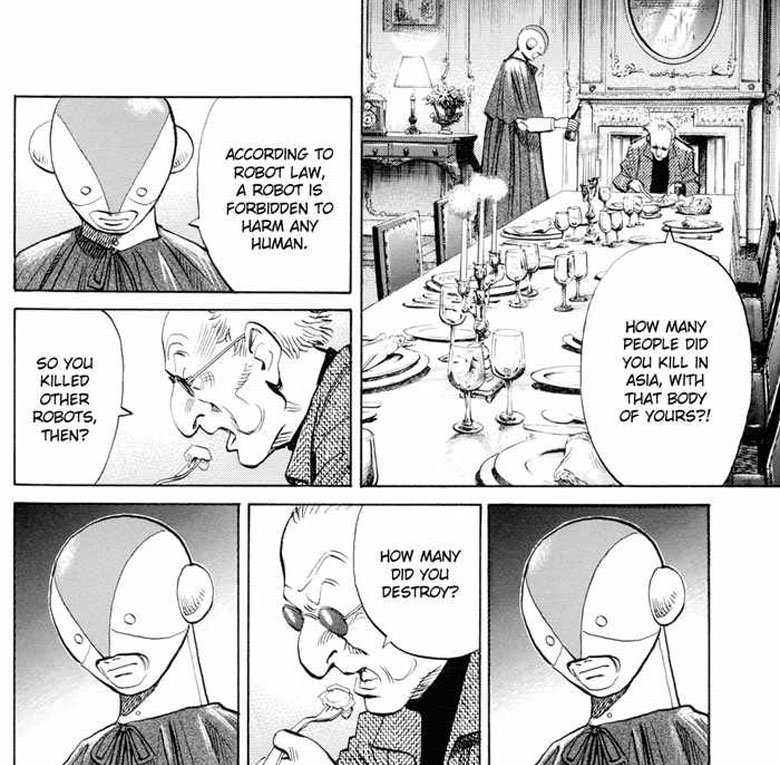

Where Urasawa's version really shines is in the smaller stuff. Gesicht in particular provides some of the story's most memorable moments, from the Silence of the Lambs-style visits to a murderous, human-hating robot imprisoned in a dungeon built around the spot where he fell in battle, to an early scene when he tells an older model robot that her husband has been killed. Rather than being a human-like android like Gesicht or Atom, she looks like something out of The Jetsons, with a face that remains completely incapable of expression even as her heart is breaking.

Gesicht delivering bad news

It's one of the story's most affecting scenes, and another one comes in the chapter about North #2.

One of the changes to Urasawa's story is that it takes place after a global war that involves robots, during which the United States of Thracia invades Persia looking for "robots of mass destruction" (I said it was good, I never said it was subtle). That addition to the plot re-contextualizes all the robots as war heroes, with Atom being hailed as an emissary of peace rather than a soldier, and allows Urasawa to deal with a different set of consequences and motivations for his characters. Epsilon's children, for instance, become the orphans of war, and characters like Brando and Heracles as robots created for war who became celebrities in crowd-pleasing combat sports.

North #2, however, deals with something different. His section of the story finds him working as the manservant (robotservant?) for a bitter but masterful composer with failing eyesight named Duncan, in an effort to learn how to play piano and create music himself.

North #2

Over the course of his part of the story, which in the original version takes all of seven pages, Duncan's initial hatred of North and what he sees as a synthetic, soulless mockery of life and creation is contrasted with North's stoic silence, which slowly gives way to the realization that he's deeply traumatized by his part in war. His effort to learn music isn't a mockery of humanity, it's because music is the only thing in the world that gives him comfort after serving in a war where he was made to destroy others like himself.

When Pluto finally arrives for the conflict, it happens almost entirely off-panel. Urasawa instead stays with Duncan as he observes the distant, deadly battle, finally understanding him.

And that's just what happens in the first of eight volumes.

The underlying message of both Astro Boy and Pluto

Like The Question—like the best darker takes on Batman, even—Pluto succeeds because it builds on what was already there. There's never the sense that Urasawa is ashamed of even the goofiest parts of the original story. He throws in some of the silliest pieces of the original Astro Boy stories, like police cars that are inexplicably shaped like cartoon dog heads.

That's what makes a darker reboot work. Darkness for the sake of darkness is boring, and darkness for the sake of insecurity is easy to spot from a mile away, giving you a story that starts off defensive rather than believing in its own premise. But when that darkness comes with nuance, with layers, with the kind of craftsmanship that you can see on display in Pluto or The Question, it adds to the story in a way that can coexist with pure, lighthearted adventure rather than detracting from it.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."