The Fantastic Beasts Franchise Has A Real Problem And It Isn't A Secret

Warner Bros. could have taken the Wizarding World anywhere when the "Harry Potter" film series ended. "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2" made over $1 billion as the highest-grossing movie of 2011 (via Box Office Mojo), and the "Harry Potter" pop culture behemoth permanently entrenched an imaginative, low-fantasy world ripe for mining new stories from beyond the experiences of a boy wizard at boarding school.

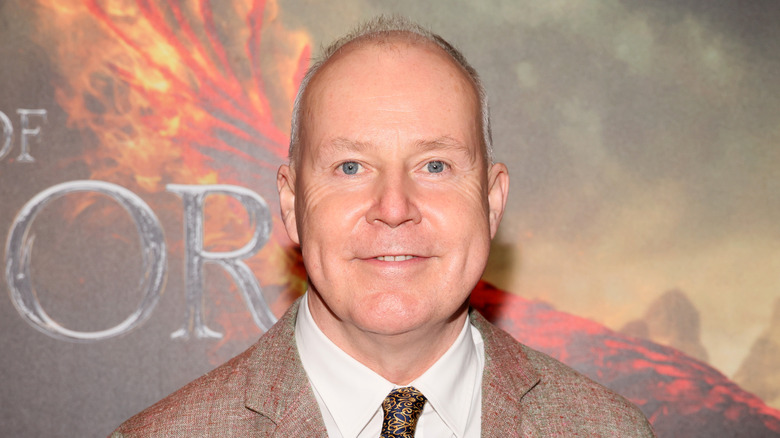

When J.K. Rowling and Warner Bros. regrouped to start expanding the "Harry Potter" film universe, Rowling herself pitched the idea for "Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them" — a series that, three films and 10 years later, can be charitably described as a mixed bag (via Deadline). The prequel/spinoff series sees Rowling herself write the screenplays, unlike the previous films that were adapted from her novels. Rather than make an inspired creative choice to help craft the Wizarding World's expansion, Warner Bros. went right back to director David Yates, who helmed the final four "Harry Potter" films.

With early reviews for "Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore" pouring in, it's grown clearer than ever that change is needed in the Wizarding World. Warner Bros. would do well to reassess who should sit in the directors' seat if it wants to save the franchise's place in pop culture.

David Yates' Wizarding World is dark and boring

David Yates' vision of the "Harry Potter" universe is dark. Yates stepped into the Wizarding World at a turning point in the franchise; "Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix" shows how Voldemort's (Ralph Fiennes) return starts corrupting the magical government. Authority figures are rendered actively untrustworthy for Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) as he struggles with guilt over Cedric Diggory's (Robert Pattinson) death and the breakdown of a mental barrier between his mind and Voldemort's. It's heavy stuff.

The series only takes a more adult tone as Harry comes of age amid a full-blown wizarding war. To achieve a darker tone, Yates quite literally makes each frame of his films darker, to the point that a compendium of color grading across the "Harry Potter" movies makes the switch to Yates' films obnoxiously clear (via Reddit). Try throwing one of the later films on in daylight; it's hard to tell what's happening on screen during nighttime scenes.

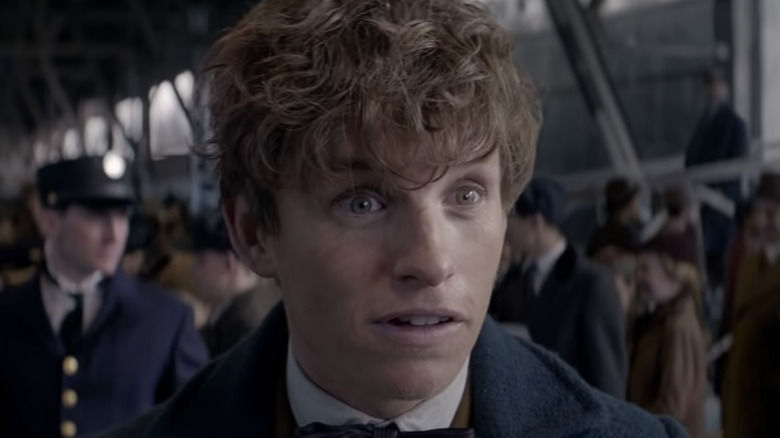

Yates' visual style remains blandly dark in the "Fantastic Beasts" movies. The movies promised to take fans to new locations populated by wizards all across the globe, but without fan-favorite backdrops like Hogwarts or the Burrow, Yates fails to conjure new locations or characters that stand half as memorable. Newt Scamander (Eddie Redmayne) and his suitcase of magical creatures travel from one bland, early 20th-century city to the next, resulting in trailers for "Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore" relying on scenes set at Hogwarts to draw fans back in rather than showcasing anything new.

The first four Harry Potter films injected new life with new directors

Remember when Harry Potter first arrived at Hogwarts, made new friends, and felt like he actually belonged somewhere for the first time in his life? Director Chris Columbus bathed the first two "Harry Potter" movies with a warm, golden color palette, indicating a fresh start and warm welcome for the neglected orphan turned famous boy-wizard. Hogwarts felt like the expansive and lively castle presented in J.K. Rowling's books, complete with moving staircases, paintings that interact with passersby, and resident ghosts who make friends with students. The magical school inspires as much awe for audiences as it did for Harry himself.

When the series made its initial pivot to darker material, Warner Bros. brought on Alfonso Cuarón to make "Harry Potter and the Prison of Azkaban." Cuarón created some of the franchise's spookiest imagery with dementors and werewolves, as well as some of its most endearing — like Harry flying on the majestic hippogriff Buckbeak. "Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire" switched directors again; Mike Newell infused the conspiracy-laden story with the authentic feel of a British boarding school, complete with a school dance as awkward as any teenager's first time at prom should be.

The first four "Harry Potter" movies make great efforts to keep the franchise visually lively. In installing David Yates as the Wizarding World's only director for so long, Warner Bros.' movies have stopped innovating what magic looks like, sounds like, and feels like.

Warner Bros. forgets that magic is supposed to be fun

In J.K. Rowling's books and the early "Harry Potter" films, it's constantly noted that witches and wizards are strange people. They opt for cloaks and pointy hats over regular muggle fashion; when they must wear normal clothes to blend in, Harry Potter often spots wizards who have no sense of fashion whatsoever. Arthur Weasley (Mark Williams), a character who is depicted as more familiar with muggles than most wizards, struggles with regular currency and questions Harry about the functionality of rubber ducks. Magic is used for inventive, practical purposes — there is no better example of this than in "Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire," when Harry enters a small tent at the Quidditch World Cup to find a magically-enhanced interior that looks more like a hotel suite.

Under David Yates' direction, Warner Bros. has failed to innovate the visual style in the "Fantastic Beasts" series beyond where the "Harry Potter" films stood when he took over. Newt Scamander's primary object of fascination, a magically enhanced suitcase that he can climb into to enter his magizoology workshop, is even a re-tread of the very same magical feat Harry gapes at within the tent. The "Fantastic Beasts" movies find comfort in diminishing returns, from an over-reliance on John Williams' "Hedwig's Theme" to the bizarre decision to cram Dumbledore's (Jude Law) backstory into a movie series initially pitched to be about a magical animal enthusiast.

If Warner Bros. wants the Wizarding World to recover commercially and critically, they really should start with injecting new life behind the camera.