Why Will Smith's Oscars Ban Doesn't Go Far Enough

A lot happened at the 2022 Oscars. That evening, the twice-nominated Jane Campion became the third woman ever to win the award for Best Director, while Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson's historically and culturally invaluable "Summer of Soul" took home the award for Best Feature Documentary. A Latinx musical won Best Animated Feature Film, and "CODA" star Troy Kostur became just the second deaf actor in history to win an Academy Award. Later, in her acceptance speech for Best Actress, Jessica Chastain addressed the legislation currently serving to further marginalize those within the LGBTQ+ community (via YouTube).

But none of this is what people will remember about the 94th Academy Awards. Instead, they'll remember Oscar winner Will Smith's notorious on-screen slap of host Chris Rock. In the minutes, hours, and headlines following the event-within-an-event, the slap birthed a flood of reactions, while the evening's historically relevant victories slipped further and further away from the discourse. Clearly, The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences had to respond to the outburst, and fast.

Smith quickly apologized and resigned from the Academy, and the organization punished the actor with a decade-long ban from attending any of its events (via CNN). But however one feels about what the Academy did with regard to Smith, it's what the Academy didn't do with regard to its own history of condoning violence that makes the ban both hypocritical and wholly inadequate. The ceremonial ban of an individual member — importantly, a step not taken against white celebrities who committed far greater offenses — does nothing to prevent future violence. It's a statement alright, but one that fails to enact any sort of meaningful change.

Coming from the Academy, Smith's ban is too little, too late

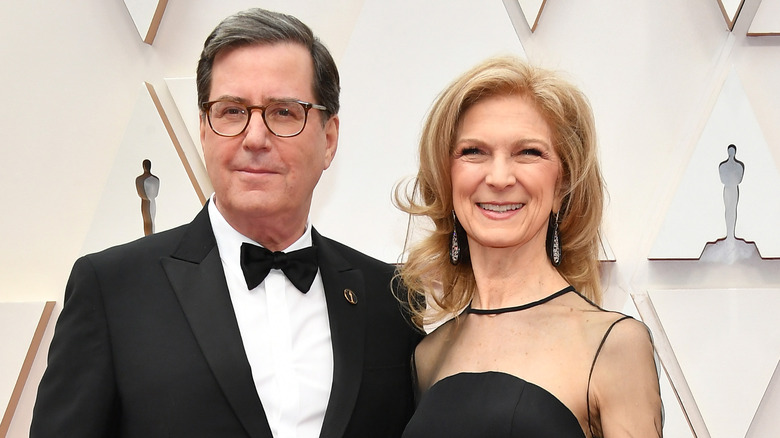

In a glorified memo entitled "Open Letter to Our Academy Family," President David Rubin and CEO Dawn Hudson did technically apologize, but only for their inability to respond to Smith's actions during the actual telecast of the event. "During our telecast," the letter reads, "we did not adequately address the situation in the room ... This was an opportunity for us to set an example for our guests, viewers and our Academy family around the world, and we fell short — unprepared for the unprecedented" (via Twitter). They may as well have said that they were "too shocked" to know what to do in the moment.

Smith's outburst most certainly was an opportunity for the organization. However, given the litany of other opportunities they've been given to set an example (not to mention the decades and decades worth of time they've been given to do it), their claim of contrition feels less like a step forward and more like a child apologizing for accidentally spilling their juice in the hopes it will distract from the fact that they've just intentionally set fire to the neighbor's house.

What's more, the subsequent outcry from Smith supporters and the assertion that this example would never have been set using a white celebrity (via LA Times), has to be taken seriously. The Academy, after all, has a history of looking the other way when it comes to its members' behavior.

The Academy needs to take more responsibility and further action to bring about change

In 2002, Best Actor winner Adrien Brody planted an aggressive kiss on presenter Halle Berry, who would later tell "Watch What Happens Live" host Andy Cohen that the embrace and unprompted make-out session were both unscripted and utterly baffling. Brody won for his performance in "The Pianist" — the same film for which convicted sex offender and then-fugitive Roman Polanski earned both a Best Picture nomination and a Best Director win, neither of which were ever revoked.

Importantly, the Academy's support of the director came a full 26 years after he pled guilty to "unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor," and was indicted by a grand jury on six felony charges, including the rape of a 13-year-old child (via AP News). Even if the Academy had been "unprepared for the unprecedented" when they nominated Polanski for best director in 1981 (a whole four years after Polanski's indictment), there's no excuse for awarding the offender later accolades, nor for allowing him to keep them even after the organization officially expelled him ... in 2018 (via Variety).

Of course, the Academy's always fostered an atmosphere wherein sexual assault, bigotry, harassment, and violence are arguably condoned and certainly ignored. Men behaving badly in the Academy at large and the Oscars in particular is anything but unprecedented.

The Academy has a history of looking the other way

In 1973, at the 45th Academy Awards, activist Sacheen Littlefeather accepted (or rather, rejected), Marlon Brando's Oscar for his performance in "The Godfather" on behalf of the actor, who'd chosen to boycott the ceremony in protest of the industry's treatment and portrayal of Native Americans. As Littlefeather delivered her speech, no fewer than six security guards held John Wayne back, as the notorious movie cowboy — who'd won an Oscar for "True Grit" just three years prior (via IMDb) — attempted to storm the stage. "He was coming towards me ... forcibly," Littlefeather recounted in an interview with The Guardian. "He had to be restrained."

The same evening, the outlet reported, future four-time Oscar-winner Clint Eastwood joked about accepting an award "on behalf of all the cowboys shot in all the John Ford Westerns over the years." To date, neither the actors nor any of their backstage supporters who heckled and harassed Littlefeather with "Native American war cries ... and miming chopping with a tomahawk" have faced any official consequences from the Academy for their public outbursts.

Over four decades later, the organization appeared to be rounding a corner when it charged a "specially-formed task force" with constructing a letter that went out to all its members outlining the Academy's new Code of Conduct (via Vulture). The move was a response to the Me Too movement, but the code itself — a broadly-worded two-paragraph statement approved by its Board of Governors – is plagued by the same fatal flaw as the 10-year ban of Will Smith: It fails to acknowledge the Academy's historic complicity in some of the very behavior now "officially deemed" unacceptable.

Its Code of Conduct means nothing if the Academy itself doesn't abide by the rules

"There is no place in the Academy for people who abuse their status ... in a manner that violates recognized standards of decency." So reads the Code of Conduct.

It's a heck of a statement to make, considering how many of its former winners have been accused, indicted, or convicted of crimes far more serious than Smith's. Two-time Oscar winner Mel Gibson, for instance — a known anti-Semite charged with domestic abuse in 2010 (via EW) — has yet to face any reprisal for his criminal behavior. Neither, famously, has imprisoned sex offender Harvey Weinstein. Like Polanski, Weinstein was expelled from the Academy (via NPR); but also like Polanski (and Gibson), Weinstein still boasts both an Oscar nomination and a 1998 win (via IMDb). If he were allowed personal property in prison, he could keep his statue on the shelf of his personal cell. Clearly, there is "a place in the Academy" for these literal bad actors.

This hypocrisy was not lost on The Atlantic's Jemele Hill. In "The Two Americas Debating Will Smith and Chris Rock," she writes, "If the Academy chooses not to allow Smith to present an award next year ... that's fine. But taking away Smith's Oscar would be absurd" considering Weinstein, Polanski, and Gibson still have theirs. Granted, Smith was permitted to keep his award, but the notion that it was ever in danger of revocation (via the NY Post), while the formers' were not, is a major part of the problem. The Academy's refusal to clearly outline its standards allows it to react to each situation differently — sometimes in the moment and sometimes decades later. It's also what allows the organization to make an example of Smith, while doing nothing to acknowledge its own major missteps.

Smith's slap pales in comparison to the Academy's own violence

Over the course of its near century-long history, the Academy has given out over 3,000 of its instantly recognizable statuettes (via Oscars Archive). It's understandable that an organization whose most famous celebration was first established the same year Herbert Hoover was elected to office is going to have made some decisions that, 96 years later, seem a bit problematic.

But this is 2022, not 1929. It's well within the Academy's power to acknowledge its own demons and attempt to rectify its mistakes. In fact, it's more than within its power. Given the organization's prominence — its "status, power and influence," to use its own words — it has a cultural and ethical responsibility to call itself to a higher standard.

Historically, the Academy has issued only a handful of nomination revocations, all based solely on the eligibility of the work in question (via EW). In fact, only one awarded Oscar — "Young Americans" 1968 win for Best Documentary — has ever been rescinded, and it was because the film's October 1967 theater release rendered it ineligible to compete in the '68 awards (via ABC). To be fair, and as IndieWire points out, the Academy's refusal to revoke awards for "issues unrelated to the quality of the work" appears rooted in the mistakes it made during the infamous Red Scare of the 1950s.

If that's the case for the Academy's bullheaded commitment to separating the art from the artists, it may be an overcorrection for a mistake that's no longer relevant in the context of 2022. Polanski, Gibson, and Weinstein aren't victims of political paranoia, but rather bonafide, convicted sex offenders and criminals. The mere comparison is a bare insult to all the talented mid-century professionals who had their careers ruined by the Red Scare.

The Academy's pearl-clutching isn't just hypocritical, it's harmful

As Milkee Bekele reminds us in The Mac Weekly, last year's Oscars ceremony, held at Union Station in L.A., "displaced unhoused residents of Union Station and relocated them, completely wiped out encampments of the residents," and forced "COVID-19 testing sites set up at Union Station [to be] relocated to other complexes much further away from the station, making it harder for the access of disabled residents of the area."

The physical displacement of an already marginalized population is violent. Complicating access to potentially life-saving resources during a pandemic is violent. Let's not pretend the Academy has any issue with violence. Punishing an actor who — to the best of everyone's knowledge — has never committed a crime outside of his slap isn't just hypocritical, it's harmful, hollow, and counterproductive.

If the Academy is at all sincere in its desire to be, as its Code of Conduct claims, an organization that "values ... human dignity, inclusion, and a supportive environment that fosters creativity," it's going to have to take a long, hard look at its own actions, and strive to remedy its mistakes in a way that actually translates into substantive change. But what exactly would that translation look like?

The Academy can do better, and it must

Currently, all the Academy has done is attempt to distance itself from the actions of its members, even as it condones them. Thus, Smith's ten-year ban doesn't go far enough for the simple reason that it points a finger at, and inflicts a punishment on, a symptom of the problem, rather than addressing the root: that is, the Academy's own shortcomings and history of systemic violence and various forms of abuse.

These shortcomings, mistakes, and failures to act could easily be addressed, and used as a step toward creating real and lasting change. Revoking convicted criminals' accolades would be a start, as would publicly apologizing for its decision to nominate Polanski decades after his indictment. Vaguely-worded memos to its members outlining an equally vague and lofty ethos does nothing to remedy or work toward healing this legacy of harm and indifference. As the Greater Good Science Center in Berkeley, CA explains, apologies that "fail to acknowledge the specific offense" ultimately "minimize the legitimacy of the offended person's grievances." Telling its members that the Academy is "categorically opposed to any form of abuse, harassment, or discrimination" without publicly apologizing, for instance, to Sacheen Littlefeather for the abuse she suffered in 1973, is a useless gesture.

None of this is to say that the Academy's failures caused Smith to assault Rock, nor should this take be interpreted as condoning Smith's outrageous behavior nor advocating for a softer punishment. But until the Academy backs its sanctions with real reform, it's simply more of the same "do as I say, not as I do" toxicity, and that rot runs deep. Banning Will Smith from the Oscars for 100 years wouldn't be enough to root it out.