Things Only Adults Notice In The Sandlot

If you grew up with a bunch of clam-shell VHS tapes, it's a safe bet that one of them was 1993's "The Sandlot." Along with the Disney classics and other kid movie staples from the late '80s and early '90s, "The Sandlot" has earned a place in our memories as a hazy, earnest coming-of-age story about good friends and the love of the game, baseball specifically. A patient, sweet movie about the simple pleasures of making friends and playing ball, watching it in the modern age may as well be meditation when you compare it to the non-stop freneticism of things like the "Minions" franchise.

It might shock you, but we are rapidly approaching the 30th anniversary of the movie's release next year. You might have kids of your own to share it with or just wonder how much of it you remember accurately. Revisiting a beloved childhood movie can be risky: you either reconnect with your inner child, realize that either you've lost some sort of innocence as a viewer in the last few decades, or feel the movie just doesn't hold up to the way it hit your child-sized brain. For better and worse, here are the things about "The Sandlot" only adults notice.

There's hardly any actual baseball

One of the first things that's jarring when you revisit "The Sandlot" as an adult is the near-complete lack of any literal baseball games in a movie that's so in love with the sport. The titular sandlot, a baseball diamond on an abandoned property in between houses, is just a space where our nine main characters work on fundamentals constantly and never play an actual game. Benny, the most skilled player, orders everyone around and hits them fly balls or grounders, and occasionally they hit live pitches, but they never keep score. They just go to the sandlot every day and do random baseball-adjacent stuff.

As if to rub it in, the only time that they're challenged to a game by a local little league team, the movie just condenses the game into a montage of our ragtag heroes making plays and scoring runs, essentially fast-forwarding through all the game action to the Sandlot gang celebrating their victory after it's over. There's no explanation of why our main characters aren't in little league (perhaps their parents can't afford the fees?) and no indication of how their constant scrimmaging with one another contributed to winning the game. For a movie so in love with baseball, "The Sandlot" forgets to include even a moment of "bottom of the ninth, two outs" melodrama that makes baseball movies compelling.

Adult Scotty Smalls has led a boring life

"The Sandlot" is a childhood story narrated by the grown-up version of main character Scotty Smalls in the present day. He refers to the summer of '62 as "the greatest summer of my life" and calls the situation with the Beast and the Babe Ruth ball the "biggest pickle" he's ever been in multiple times. This is not to take away anything from the magic of childhood, the bond between new friends, and the triumph of a group of children over what turns out to be a pretty friendly dog, but this is the best summer of your life, Scotty? You're a grown adult, an announcer for a Major League Baseball team. Surely one or two summers were a little more interesting than the one when you made some new friends and destroyed your stepdad's prized possession.

Has adult Scotty never fallen in love? Is working for the MLB just kind of boring? Or is it a case of the screenplay for "The Sandlot" working overtime to imbue the events of the film with more significance than they merit? That's all in the eye of the beholder, but as an adult yourself, you likely know that life generally gets even more interesting when you grow up and stop hyperbolizing your childhood exploits.

Scotty's inability to throw a ball beggars belief

One of the strangest plot points in the first half of "The Sandlot" is Scotty's inability to throw a ball. Though he's described as an "egghead," he's clearly old enough to understand basic physics and construct elaborate Erector Sets. But he's so clueless as to how to simply throw a ball, you start to wonder if he's an alien posing as a human. In more than one scene, instead of throwing a ball, he slowly and awkwardly walks it over to the person instead.

With patient kindness, Benny has to ask if Scotty's ever had a paper route to see if he's familiar with the concept of throwing objects at all. You can see what the movie is going for — insofar as Scotty growing up without his birth father has left him a little behind in the sports department — but unless he doesn't know what the words "throw" and "catch" mean, his issues stray from relatable to absurd pretty quickly.

The Sandlot is better when it's pure fantasy

What's striking about "The Sandlot" from an adult perspective is how the film is kind of stilted and aimless but comes alive whenever the Beast is involved in the story. The almost mythic aspects of the dog that devours home run balls is the part of the story that feels the truest to the way childhood memories are stretched and exaggerated and the vivid imaginations that children have. With most of the story is presented lackadaisically and episodically, the story of the Beast and the quest to retrieve the Babe Ruth ball provides "The Sandlot" with all of its momentum.

The two best parts of the movie by far are when Squints tells the legend of the Beast during a sleepover and, of course, the madcap sequence when the boys try to retrieve the Babe Ruth ball with an escalating series of contraptions. These sequences — whether it's the Beast devouring errant thieves in a black and white fantasy sequence or the vacuum cleaners exploding and covering Scotty with dust — are the parts of "The Sandlot" that live in our memory because they capture the fairy-tale-like understanding of the world that we all have before we grow up.

Scenes with Wendy Peffercorn are wildly uncomfortable

Of all things, the aspect of "The Sandlot" that's aged the worst is the scene where Squints pretends to drown in order to kiss Wendy Peffercorn. Certainly, in the post-#MeToo era, a child kissing a teenage woman without her consent is the first thing that would get axed from the script, but even for the time it was released, it stands out as a squeamish element in a movie that's squarely aimed at kids.

In the immediate aftermath, Wendy hits Squints and calls him a pervert, and we learn that the entire gang is subsequently banned from the pool forever. But it's clear from the moment that "This Magic Moment" kicks in on the soundtrack when the "kiss" takes place that "The Sandlot" thinks this moment is triumphant and not uncomfortable. Adult Scotty swoops in to narrate about it, celebrating that Squints "had kissed a woman. And he had kissed her long, and good." As the years pass, it's just a more and more jarring inclusion in an otherwise innocent and family-friendly film.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Ham Porter is the film's true MVP

There's just no way that "The Sandlot" would have endured over three decades without Patrick Renna's performance as Hamilton "Ham" Porter. Watching it again, you realize that despite the nine members of the principal cast and the distracting presence of Denis Leary as a completely humorless character, it's Ham that has nearly all of the laugh lines in the movie. From his impression of "The Great Bambino" Babe Ruth to the hilarious exchange with Scotty about s'mores and the iconic "You're killing me, Smalls!", Ham is by far the most memorable presence and the most tonally in line with the cartoon whimsy that "The Sandlot" brings in its best moments.

None of the child stars of "The Sandlot" have really gone on to stardom, but Patrick Renna's performance makes you wonder "what happened to him?" the most. Though he's worked steadily in TV and film ever since but has never recreated the magic that he had as Ham.

What's wrong with being an egghead?

One of the strangest things about "The Sandlot" is that even for a kid's movie, it has little to no character development in its story. The tension between Scotty and his stepdad looms over the film but gets waved off by the voiceover at the end of the movie when adult Scotty mentions that he just got grounded for a week and then they were cool. The biggest tension, or at least the nominal source of conflict when the movie begins, is that Scotty is "just an egghead" that has no friends and doesn't know how to play sports.

As an adult, you wonder: What's so bad about being an egghead anyway? As the closing voiceover indicates, literally only two members of the sandlot crew go on to play organized baseball of any kind. The only thing close to a resolution to Scotty's identity crisis is sort of implied when the rest of the gang embraces his elaborate designs for devices to rescue the baseball from over the fence, but it's not referenced or tied off aloud.

Benny's dream comes out of nowhere

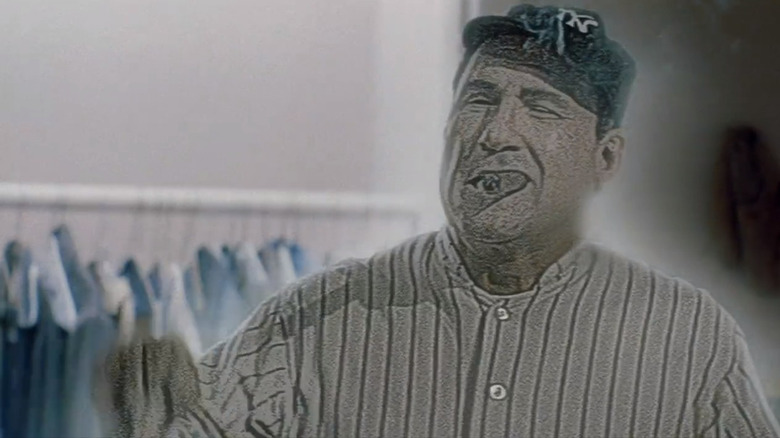

"The Sandlot" is clearly Scotty Smalls' story. He narrates it, we see how finding the sandlot and learning baseball helps him deal with moving and his tense household, and the central conflict of getting the baseball back is all rooted in the stakes of his life. So by far the strangest beat in the story is when, abruptly, we are treated to an extended dream sequence of Benny's where a vision of Babe Ruth convinces him to leap the fence and get the ball back himself.

It's a delightful performance from veteran character actor Art LaFleur as the Sultan of Swat, and it's a perfect touch in keeping with the way the kids have lionized "the Babe" over the course of the film. But since we don't know anything about Benny and have no reference points for why he wants to play baseball, why he mentors the entire rest of the Sandlot, or what exactly he has to prove to anyone, we don't feel much of anything when Dream Babe tells him vague things about greatness. It's the kind of thing that might be nitpicking if you're a kid, but when you've grown up and seen a few movies, it's pretty basic stuff: Scotty should be involved in the emotional climax of the story, or the story should be more about Benny in the first place.

Mr. Mertle couldn't have played with Babe Ruth

It's wonderful casting to have James Earl Jones, just a few years after appearing in "Field of Dreams," turn out to be the owner of the Beast. It's a bit on the nose, but still wonderful that he turns out to be a former baseball player whose blindness forced him to retire. But in making Mr. Mertle such a good friend of Babe Ruth that he calls him "George" and has a spare ball signed by the 1927 Yankees on hand, "The Sandlot" is playing fast and loose with some basic sports history that takes you out of the movie a little bit if you've even Wikipedia-ed the relevant people.

Simply put: Babe Ruth retired from baseball in 1935, and Jackie Robinson didn't break the color barrier in major league baseball until 1947. So it's impossible for the African-American Mr. Mertle to have been teammates with the Babe on either the Red Sox or Yankees during his legendary career. It's certainly not impossible that they knew each other, but Mr. Mertle's casual indication that he knew "George" so well paints a much rosier picture than the reality of being segregated at the time in an entirely different league.

Scotty's stepdad should be way happier about the Murderers' Row ball

After all the zany rescue attempts and the Beast's epic pursuit of Benny all over town, Scotty ends up with a ball signed by the entire roster of the 1927 Yankees to replace the one signed by Babe Ruth that he stole from his stepdad. As a kid, you think, "Hey, that's pretty neat," but as an adult with even a passing understanding of how much value sports memorabilia can bring, you're completely gobsmacked. The '27 Yankees, led by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, are widely regarded as the best team of all time, nicknamed "Murderers' Row."

It's a way more valuable ball that Scotty's wet-noodle of a stepdad gets at the end of the film, and all he can do is kind of widen his eyes in response. While there are many signed Babe Ruth balls in circulation, a ball signed by the entirety of the team that's become the shorthand for greatness would be worth a small fortune (at least $125,000 in today's money, according to one appraiser). Honestly, Bill should have rewarded Scotty, not grounded him for a whole week.

The Sandlot feels like it was written by a child

Even though it is ostensibly narrated and related to us by an adult Scotty, "The Sandlot" truly has the wandering pace and meandering focus of a story told by a child. This is to its credit, especially in the sequences with the most imaginative touches and giant dog puppets, but the cracks in the screenplay truly shine through whenever Scotty interacts with adults. When his mother finds a lonely Scotty in his room and asks with wide-eyed earnestness, "Did you make any friends yet?", it really seems like she's honing in on his exact fears in the unsubtle way that Scotty himself would recount it.

It's even worse with stepdad Bill, whose unnamed job is somehow something that keeps him so busy he's working from home in the year 1962 and absurdly reluctant to teach Scotty how to play catch. Basically, it's almost like "Drunk History," but with being a child instead of alcohol. Regardless, "The Sandlot" is the kind of beautiful mess that charms in spite of its flaws, engenders a love for baseball while hardly showing it, and generally keeps you smiling in a way that makes you feel like a kid again.