13 Thrilling Movies To Watch If You Like David Fincher

David Fincher is in the rapidly-shrinking class of filmmakers who are, themselves, box office draws. Like Scorsese and Spielberg, he's an exacting auteur with impressive range. Like Tarantino, he blends music and violence to disturbingly beautiful effect. Like the Coen Brothers, he spins a captivating yarn out of a crime. Like the Andersons (Paul Thomas as Wes), he's precise in the composition of his images. And like Christopher Nolan, a contemporary to whom he's most often compared, he elevates action with clever conceits and a modern aesthetic. What sets Fincher apart is how effortlessly he combines his poppier and pulpier influences with his more literary inspirations. The result? Works of art that aren't a chore to watch.

Fincher got his start directing music videos (he was the visionary behind Madonna's "Vogue," Paula Abdul's "Straight Up," and George Michael's "Freedom") and he's experimented with several genres ("The Curious Case of Benjamin Button," "The Social Network," and "Mank" were critically acclaimed departures), but he's best known for his thrillers. Sometimes they're ripped from the pages of bestsellers like "Fight Club," "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo." or "Gone Girl." Sometimes they're original creations like "Panic Room," "The Game," or "Se7en." Though each has its own distinct vibe, Fincher thrillers do have a few things in common. They're gritty and twisty but impeccably made. They're psychological but at a bit of an emotional remove. They're fascinated by identity and past sins.

Next up for Fincher is a noir thriller called "The Killer," starring Michael Fassbender and Tilda Swinton; it's expected to premiere on Netflix sometime in 2022. Until then, fans can get their fix by watching these 13 movies, which all live up to the standard of Fincher's own filmmaking.

Rear Window (1954)

This Hitchcock classic is a film that Fincher cites as a favorite. That checks out, as its fingerprints can be found on many of Fincher's own movies. He reportedly pitched "Panic Room" by comparing it to "Rear Window," which his father took him to see as a child. It sparked his passion for the art form, and Fincher frequently and liberally samples from his cinematic roll model (stylized credits, early twists, icy blondes, zooms, and much more). But "Rear Window" didn't just enchant David Fincher; it helped set the stage for every thriller that came after it in which the protagonist voyeuristically witnesses what they believe is a scandal or a crime.

James Stewart is Jeff, a news photographer stuck in his apartment with a broken leg during a heat wave. He's visited by his girlfriend, Lisa (Grace Kelly), and his nurse, but mostly he passes time spying on the exploits of his neighbors. There's a newlywed couple, an older couple with a dog, a salesman with an invalid wife, a piano player, and two single women. The plot plays out like a reverse murder mystery. Jeff is certain that a crime has been committed, but he can only guess at the particulars, and — fearing he and his neighbors are in danger — he must solve the puzzle from the confines of his own living room as everyone else is free to move about.

"Rear Window" impressed critics with its constantly building tension and use of voyeurism as a device to further both its plot and themes. It's one of four Hitchcock films to appear on the American Film Institute's 100 years...100 movies list, where it's ranked 48th.

Memento (2000)

Fincher and Christopher Nolan will be forever linked because they both broke through around the turn of the century with mind-bending movies that attracted similar audiences. For Fincher, it was 1995's "Se7en" and 1999's "Fight Club." Nolan had made a well-received, extremely low budget thriller called "Following" in 1998, but he became a household name with 2000's "Memento."

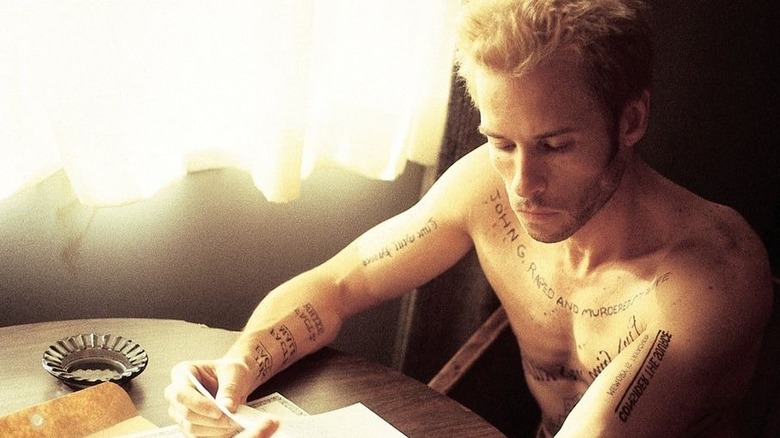

"Memento" stars Guy Pearce as Leonard, a former insurance investigator who — quite problematically — is suffering from anterograde amnesia after he and his wife were brutally attacked. The film begins as he shoots a man in the head because he left himself instructions to do so on the back of a Polaroid. Since he can't retain new short-term memories, he's developed a complex but not entirely foolproof system to orient himself each day that utilizes notes, those photos, and — for the most important information — tattoos. One of those tattoos reminds him that he once denied the insurance claim of a man who struggled with the same affliction. Leonard endures this torturous, fleeting reality so that he might one day avenge his wife's rape and murder, but his mission is complicated by the fact that he can't really trust anyone, including his friend Teddy (Joe Pantoliano), a bartender named Natalie (Carrie-Anne Moss), or himself.

This groundbreaking neo-noir introduced Nolan to the world as a creative force to be reckoned with. "Memento" is an early example of his penchant for the manipulation of time (it unfolds according to two timelines; one is told in black and white, the other in color) and conflicted, unreliable narrators. It received a five minute long standing ovation after its premiere at the Venice Film Festival, and it went on to become an enormous word-of-mouth success.

Barton Fink (1991)

David Fincher isn't just a member of the Hollywood establishment; he's as big a fan of movies as anyone, so much so that the entertainment industry itself became the subject of one of his most celebrated films. "Mank" — set in 1930s Los Angeles — tells the story of Herman Mankiewicz, a screenwriter who worked on one of Fincher's other favorites, "Citizen Kane." The Coen Brothers' often cover similar territory. One such title is 1991's "Barton Fink," set in 1940s Los Angeles, about a playwright-turned-screenwriter (John Turturro) unhappy with the B-movie material the studios have assigned him to pen.

While Fincher leaned away from the thriller with "Mank," "Barton Fink" leans hard into it, putting the titular character on a literal and metaphorical path to disaster. Barton has writer's block, and all the distractions that manifest from his scummy hotel aren't helping. He befriends an insurance salesman (John Goodman) as well as another author (John Mahoney) and his secretary (Judy Davis) who he hopes can help him jumpstart his stalled screenplay in time for a meeting with producers. When someone is brutally murdered and the police suspect a serial killer is on the loose, Barton fears for his life but finds that, with all the excitement, he can suddenly write again. As the words flow, the bodies pile up.

The Coens were also influenced by Hitchcock (as are surely many filmmakers), but "Barton Fink" is its own kind of noir. It uses its premise to explore challenging themes like class division and the rise of fascism, yet it has a distinct sense of humor. The film won the Palme d'Or as well as best director and lead actor at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival, and it received three Oscar nominations.

Shutter Island (2010)

Like David Fincher, Martin Scorsese's filmography include biopics and period pieces, but crime is clearly his wheelhouse. 2010's "Shutter Island" — based on the novel by Dennis Lehane — might not be Scorsese's best movie, but it's the one that shares the most DNA with Fincher's work (twists, mistaken identities, Hitchcock blondes), and it's one of the most fun to puzzle through. Scorsese's adaptation also highlights many of the same themes that seem to interest Fincher, like the fallibility of identity and the corrosive effects of social isolation and obsession.

Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Ruffalo play U.S. Marshals Teddy and Chuck, newly teamed-up partners assigned to investigate the disappearance of a female patient at a remote island hospital for the criminally insane. Inclement weather strands them there, and an uncooperative staff keeps them from making much progress which, combined with the dangerously disturbed residents, only adds to the atmosphere of paranoia. As it turns out, the real reason Teddy took the assignment was because his wife (Michelle Williams) was killed in a fire set by an arsonist who he believes might be an inmate at the facility. But as he works the cases, he begins to suspect that something nefarious is happening in the off-limits sections of the hospital, and that the psychiatrists and guards are involved.

"Shutter Island" received mixed-to-positive reviews, perhaps because it's explicitly more of a thriller and less of a prestige film than critics were accustomed to seeing from Scorsese. But it had its defenders. The National Board of Review named it one of their top ten films, and it's the legendary director's second highest grossing film to date.

Black Swan (2010)

The world of classical ballet might not seem like an obvious setting for a thriller, let alone a body horror film, but director Darren Aronofsky mines this rigorous, cutthroat, and emotionally devastating subculture to gorgeous and gory effect with 2010's "Black Swan." Natalie Portman won an Oscar for her portrayal of Nina, a rising star in a New York City ballet company falling apart under the pressure from her overbearing mother, as well as a demanding artistic director Thomas (Vincent Cassel). "Black Swan" resembles Fincher's work in its masterful construction and in that much of the story reveals itself through an increasingly unwell Nina's hallucinations.

When the previous prima donna (Winona Ryder) is forced to retire, Nina has a chance to dance the lead in Tchaikovsky's famed "Swan Lake," an opportunity that would be the pinnacle in any ballerina's career. She's technically perfect, but Thomas thinks she lacks passion. Professional ballet is notoriously competitive, so as Nina ascends, she faces backlash from other girls in the company who accuse her of seducing Thomas. Nina becomes a victim of her own blind jealously when a new member joins the company (Mila Kunis) and threatens to outshine her.

"Black Swan" gets its title from one of the characters in Tchiakovsky's ballet. In "Swan Lake," a beautiful princess dressed in white named Odette is turned into a swan by an evil nobleman sorcerer. A nearby prince is about to marry, and the sorcerer presents his own daughter — Odile, dressed in black — as if she is Odette (who has already won the prince's heart) at the ball. On stage, the same ballerina plays both parts. Aronofsky's film makes excellent use of its meta fable-within-a-fable as both the movie and the ballet spin faster and faster towards inevitable tragedy.

L.A. Confidential (1997)

Curtis Hanson's "L.A. Confidential" is made from many of David Fincher's favorite film ingredients. It's a neo-noir set in the Golden Age of Hollywood. It features Kim Basinger as a femme fatale in a role that won her an Oscar (the film itself was nominated for eight), plus more icy blonde bombshells than you can shake a stick at. And it follows a pair of mismatched cops and another (Kevin Spacey) with an inconvenient inability to ignore his conscience; Ed Exley (Guy Pearce) is the brains and Bud White (Russell Crowe) is the brawn, in the roles that made these Aussies into household names stateside.

Based on James Ellroy's book, "L.A. Confidential" is a fictionalized recounting of the types of scandals and corruption that roiled the police force, the entertainment industry, the tabloids, and organized crime in the late '40s and early '50s. Exley and White start off as foes when the former testifies again the latter's partner. Exley thinks of himself as a good guy because he's completely on the straight-and-narrow. White thinks of himself as a good guy because he's made it his personal mission to bring as many domestic abusers to justice as possible. When the local kingpin gets put away from tax evasion, creating a power vacuum, Los Angeles is rocked by a killing spree. One gruesome incident at a coffee shop arouses Exley and White's suspicions, making allies out of these former enemies. Meanwhile, Spacey's slick Jack Vincennes is feeding information to the gossip rags and vice verse, and a pimp is surgically remaking prostitutes to look like celebrities, some of whom wind up dead.

Smooth and stylish yet unflinching in its depiction of L.A.'s seedy underbelly, "L.A. Confidential" was a critical and commercial hit that had broad appeal and interesting things to say about the psychology and moral relativism of its many characters.

Oldboy (2003)

David Fincher films are often an intoxicating mix of high and low culture, and in those lowest lows, they can get provocatively dark. Park Chan-wook's "Oldboy" is an even more extreme mashup of sophistication and sadism, and, as is typical for Korean cinema, it takes its provocations to a level Fincher hasn't yet dared to go. "Oldboy" was the runner-up at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival (Quentin Tarantino served as jury president that year), and many critics including Roger Ebert sang its praises. Still, despite the appreciable ancient Greek and Shakespearian influences and the overall quality of the filmmaking, "Oldboy" won't be for everybody. It's an unapologetically upsetting movie.

Dae-su is a husband and father arrested for public drunkenness. What at first seems like it might be a brief stint in a jail cell turns into 15 years of captivity in a hotel room sealed off from the rest of the world with only a TV and a hole in the wall through which he gets food. From the news, he discovers that his wife has been killed and he's the prime suspect. One day, Dae-su is drugged and sent back into the world, where he eventually meets and falls for a young woman named Mi-Do and reconnects with an old friend, Joo-hwan. He learns that he was essentially a victim of an underground private prison system, and he has five days to figure out who abducted him and why.

"Oldboy" is a psychologically, emotionally, and physically punishing movie with a unforgettable shock ending. It's been remade twice, including by Spike Lee in 2013, but nothing can come close to the experience of watching the flawless, visceral 2003 original.

The Usual Suspects (1995)

The legacy of 1995's "The Usual Suspects" has been tarnished by sexual assault accusations against its director, Bryan Singer, and co-star, Kevin Spacey, who won the Academy Award for his supporting role (and co-starred in Fincher's "Se7en" that same year). But none of that makes the film any less brilliant.

This bloody Rubik's cube of a movie also won a well-deserved Oscar for best screenplay and was chosen as the 10th best mystery movie by the American Film Institute. Its twist ending — one of the earliest in a long string of '90s and '00s movies that pulled the rug out from under the viewer — remains one of the most talked about of all time.

In "The Usual Suspects," police recover 27 bodies from the torched wreckage of a docked ship where a mob deal has gone horrifically wrong. There are only two surviving witnesses. One is burned beyond recognition; the other's a low-level sad-sack with cerebral palsy who goes by the name Verbal Kint (Spacey). An agent (Chazz Palminteri) interrogates Kint, who recounts the events of the last six weeks in flashback, insisting that an elusive crime lord named Keyser Söze is the man behind everything.

He tells the agent that he and four other criminals — the titular usual suspects, played by Gabriel Byrne, Stephen Baldwin, Benicio del Toro, and Kevin Pollack — were brought in to participate in a police lineup involving a hijacking that none of them would admit to, and while all in one place, they came together on a plan to steal millions from some smugglers and corrupt cops. But when the plan went awry, they ended up in over their heads and beholden to the mysterious Keyser Söze. The clues are all there ... if the agent (and the audience) can piece them together.

10 Cloverfield Lane (2016)

There's nothing quite so panic-inducing as the feeling of being trapped without the possibility of escape. David Fincher captured it with "Panic Room," as did "Oldboy." So does 2016's "10 Cloverfield Lane," the sort-of sequel to 2008's "Cloverfield" that plays more like a grim thought experiment than a monster flick.

Mary Elizabeth Winstead is Michelle, a woman who wakes up in an underground bunker, chained to the wall, after having been knocked out by a car accident. She'd just left her boyfriend when her car flipped, and in her last conversation with him, he was worried about news reports of unexplained blackouts. The bunker belongs to an intimidating man named Howard (John Goodman) and he shares it with another man, Emmett, who swears he's there voluntarily, though his arm is visibly injured. Howard eventually unchains Michelle and explains their situation.

Something — aliens, Russians — has poisoned the air and killed most everything that lives on the surface. He found Michelle and rescued her by bringing her to his hideout, where he insists they must wait things out for at least a year or two. Michelle has doubts, both about the circumstances that led to her confinement and the state of affairs on the surface. For awhile, the three bunkmates settle into something resembling normal life, but soon Howard's belligerence and deceptions compel Michelle to wonder if she wouldn't be better off risking escape. Critics agreed that "10 Cloverfield Lane" made the most of its small but mightily talented cast and claustrophobic setting.

Mulholland Drive (2001)

David Lynch is a master at bringing the surreal to life on screen. The failed-TV-pilot-turned-Oscar nominee "Mulholland Drive" is arguably his best, most surreal and thrilling film, and it's the one that has the most in common with David Fincher's aesthetic and interests. As is often the case with Lynch's work, not everyone gets it, and in this case, that holds true even for people who loved the movie. In revisiting the film upon its 20th anniversary, The Ringer's Adam Nayman called it a "frustrating masterpiece."

"Mulholland Drive" isn't plotty enough to warrant much summary, and Lynch has been mum about his own interpretation of what really happens in the film. Laura Elena Harring plays Rita, a sultry brunette who survives a car accident and seeks refuge in a stranger's apartment when she can't remember who she is. Naomi Watts is Betty, a starry-eyed blonde ingenue who's staying in the apartment (it belongs to her Aunt Ruth) while she tries to establish herself as an actress. Betty helps Rita unlock the secrets of her past (curiously, there's a strange key and a large amount of money in her purse) as she attends auditions. The two begin a romantic relationship, but they also get involved with a big shot director (Justin Theroux) busy dealing with his own entanglements as the mob is bankrolling his movie.

Viewers might not have the same satisfying sense of having figured everything out after "Mulholland Drive," but the movie is rewarding in other ways. This Hollywood fever dream of a neo noir asks its audience to solve more of an emotional mystery than a literal one, and Naomi Watts' breakout performance is well worth the two hours and 26 minutes.

The Parallax View (1974)

The high-stakes worlds of politics and business can make for gripping thrillers. David Fincher has dipped his toe into the waters of governmental and corporate corruption now and then, especially with 1997's "The Game" and 2010's "The Social Network." An earlier example is 1974's "The Parallax View," which received good reviews in its day but is now seen as one of the best and most influential entries in the genre, along with the rest of director Alan Pakula's "Paranoia Trilogy." Loosely based on a novel that imagined the plight of two witnesses to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the film version fictionalizes its plot and character specifics, but it retains its allusions to the political climate of the late '60s and early '70s, and the same air of suspense.

Warren Beatty plays Joe Frady, a journalist whose girlfriend witnesses the assassination of a presidential candidate. Though the official story presented by the media is one of a lone shooter, she suspects conspiracy and fears for her life, as every other witness has mysteriously died within recent years. Joe dismisses her, but when she winds up dead, he finds himself pulled into the very conspiracy she tried to warn him about. At first, he investigates as a reporter, tracking down the deceased witnesses and looking into the circumstances of their deaths. Those avenues point to the powerful Parallax Corporation, and the only way for Joe to get to the bottom of their political machinations is for him to join them.

"The Parallax View" and its mood and themes resonate today — in a time when people seem not to trust big business, the government, or each other — every bit as much as they did when it was made against the backdrop of Watergate.

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999)

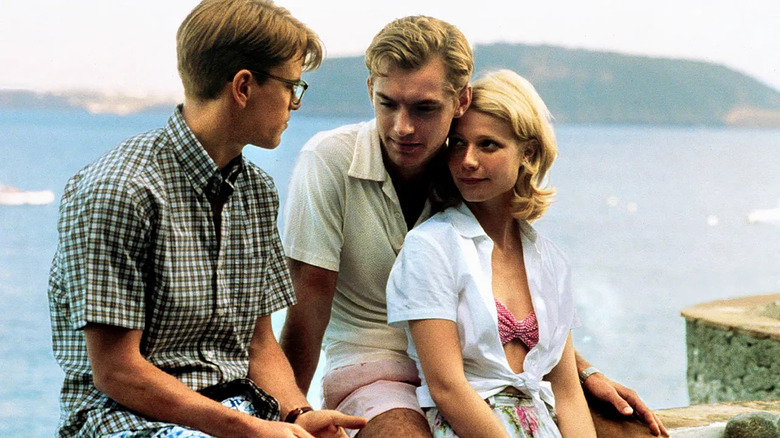

Anthony Minghella's beautiful, complex "The Talented Mr. Ripley" is more sumptuous and romantic than any thriller has the right to be. The film, which received five Academy Award nominations, lures the viewer in with its postcard-like cinematography, atmospheric score, luxurious period details, and mega-wattage triumvirate of young leads — Matt Damon, Jude Law, and Gwyneth Paltrow — all at the height of their attractiveness and fame. But it's only because "Ripley" is so alluring on so many levels that its dark side packs so much punch.

Based on a series of 1950s novels centered around the title character, "Ripley" kicks in as Tom (Damon) is mistaken for a Princeton grad and recruited by an affluent businessman to travel to Italy and convince his wayward son, Dickie (Law), to return home. The offer is too good for Tom to refuse, but on the ship across the Atlantic, he lets his imagination get the better of him and, armed with enough information, he passes himself off as Dickie. Once he arrives and makes Dickie's acquaintance and that of his girlfriend, Marge (Paltrow), the trio lives it up, carefree, until Dickie gets bored of Tom's company and starts palling around with his friend, Freddie (Philip Seymour Hoffman) again. Both Tom and Dickie have secrets, and the more time they spend together, the harder it is to keep them hidden.

"The Talented Mr. Ripley" is, like much of Fincher's work, a multi-sensory treat that still buzzes with the anxiety that anything could go wrong at any moment. And, like Fincher, Minghella allows viewers to get inside the heads of his characters so that they can sympathize with the way each is both victim and villain.

A History of Violence (2005)

If there's a unifying concern in all of Fincher's films, it's the question of whether we can really get past the horrible things we've done and the horrible things that have been done to us in the past. No movie illustrates that point better than David Cronenberg's acclaimed "A History of Violence."

Viggo Mortensen, fresh off "The Lord of the Rings" trilogy, stars as Tom Stall, an unassuming Indiana family man who owns and operates a diner. When two criminals burst in and threaten to shoot his patrons, he leaps into action, saves the day, and is hailed as a hero. The story eventually makes its way to the national news cycle, but it's not the attention Tom wants. A man (Ed Harris) who says he knows Tom by a different name shows up in town and begins to keep tabs on Tom's wife, Edie (Maria Bello), and kids, who — despite his promises to the contrary — suspect he may in fact be hiding something. As Tom reckons with his own past, he sees flashes of himself in his teenage son, Jack, who's getting in trouble for fighting at school. The disruption of their everyday life also has a surprising effect on Tom and Edie's relationship.

Cronenberg's signature movies ("The Fly," "Videodrome," for example) veer into a lane so idiosyncratically absurdist and degenerative that the term Cronenbergian exists among film buffs to describe it. In contrast, "A History of Violence" is aggressively normal ... until it's just aggressive. That renders it all the more thrilling and poignant in its commentary on the human capacity for good, evil, and everything in between.