The Untold Truth Of The Prince Of Egypt

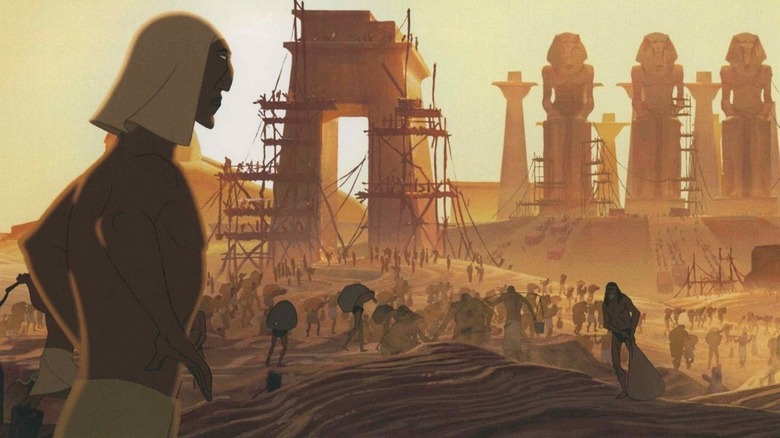

Whatever your religious beliefs or lack thereof, there's a lot to love about "The Prince of Egypt," DreamWorks' 1998 animated adaptation of the story of Moses from the Biblical book of Exodus. The studio's second animated feature after "Antz," it now stands out as one of the most beautiful animated movies ever, though it's an anomaly amongst the DreamWorks Animation library as a dark and serious traditionally-animated epic. The studio's subsequent few attempts at traditional animation ("The Road to El Dorado," "Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron," and "Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas") were less successful, and the overwhelming success of "Shrek" resulted in a shift in focus to the wacky computer-animated comedies DreamWorks is most often associated with today.

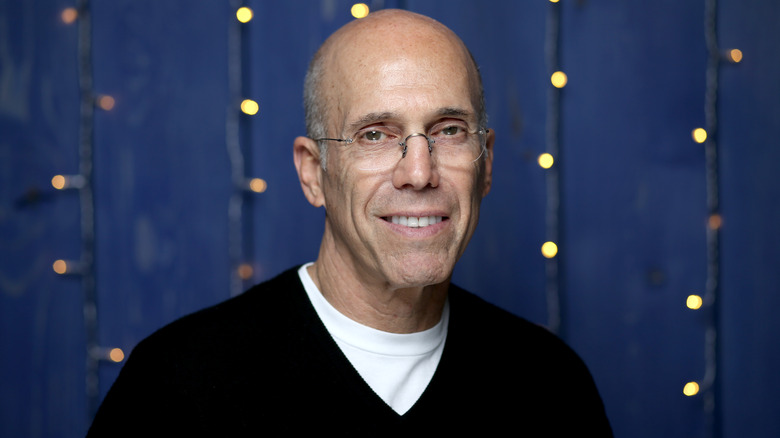

"The Prince of Egypt" was producer Jeffrey Katzenberg's passion project, an ambitious and expensive attempt to beat his former employer Disney at its own game while proving animation could be used for more mature stories than the Mouse House was willing to tackle. Doing solid but not spectacular business at the box office, it wasn't the Disney-killer Katzenberg was hoping for, but it's remained a favorite of many animation fans for decades to come. Here's the story you might not have known about how this stunning film came to be.

Jeffrey Katzenberg's big challenge to Disney

During his time as chairman of Walt Disney Studios from 1994 to 1994, Jeffrey Katzenberg shepherded an animation renaissance with hits like "The Little Mermaid," "Beauty and the Beast," "Aladdin," and "The Lion King." Great films, but there was always a formula, and when Katzenberg co-founded DreamWorks with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen, part of his goals were to challenge Disney's animation dominance with films that broke from the medium's typical kid-friendly fairy tale expectations.

At the first brainstorming meeting for DreamWorks' films, Katzenberg discussed wanting to use animation to tell larger-than-life adult-skewing stories that Disney simply wouldn't approach, along the lines of "Indiana Jones," "The Terminator," or "Lawrence of Arabia." It was Spielberg who suggested "Why don't you do 'The Ten Commandments'?" Geffen was into the idea, but strongly advised Katzenberg it had to be handled properly, telling him, "If you do it, you can't tell a fairy tales. You're going to have to go about telling this with a sense of respect and integrity that nobody's done in modern times" (via The Los Angeles Times).

Hundreds of religious and cultural consultants

Katzenberg heeded Geffen's advice, and went to a wide range of experts to try to get the story told right. Reports of the exact number of consultants on "The Prince of Egypt" vary. The Los Angeles Times reported upwards of 300 consultants, whereas The Tampa Bay Times reported 680, and The New York Times said the number was closer to 700. Whatever the exact numbers, it was an extensive outreach program, addressing both liberal and conservative leaders within the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim faiths, as well as archeologists, scholars, and Arab American groups.

Everything from the accuracy of the hieroglyphics on walls to the exact wording of certain Biblical lines was subject to adjustment based on these consultants' advice. Adaptational liberties had to be taken in turning the Exodus story into a widely accessible PG-rated film, but the film acknowledges these sensitivities upfront with a disclaimer, stating, "While artistic and historical license has been taken, we believe that this film is true to the essence, value and integrity of a story that is a cornerstone of faith for millions of people worldwide."

The first animated studio film directed by a woman

Women have been working in animation since animation was invented. In fact, the first feature-length animated film, the 1926 German stop-motion feature "The Adventures of Prince Achmed," was directed by a woman, Lotte Reiniger. At the big Hollywood studios, however, opportunities for women have long been limited. "The Prince of Egypt" broke ground as the first big-budget American animated film with a female director: Brenda Chapman, who co-directed alongside Steve Hickner and Simon Wells.

Chapman served as a story artist at Disney on films such as "Beauty and the Beast" and "The Lion King." In a 2018 interview with Polygon, she said she originally joined DreamWorks as a writer and wanted to stick to that job, but Katzenberg was "persistent" in wanting her to direct. She ended up being the main driver of the story, while Wells focused more on the visuals and Hickner on the technical challenges. Chapman would later join Pixar and begin directing "Brave," but was pushed off the film due to creative conflicts with then-studio head John Lasseter.

Animators were punished by being "Shreked"

At Disney, Katzenberg already had a history of not always making the right predictions of what would be a mega-hit. He was convinced "Pocahontas" would be the studio's next shot at a Best Picture nomination, while "The Lion King" was a side-project for the studio's "B-team" (via Tor). The "B" movie ended up breaking box office records while the "A" movie was a critical and commercial disappointment. A similar dynamic emerged in the early days of DreamWorks Animation: "The Prince of Egypt" got all the resources and attention, while "Shrek" was the struggling side-project.

Nicole LaPorte's 2010 book "The Men Who Would Be King: An Almost Epic Tale of Moguls, Movies, and a Company Called DreamWorks" quotes one anonymous animator as describing "Shrek" as "the Gulag," and saying, "If you failed on 'Prince of Egypt'... you were sent to the dungeons to work on 'Shrek.'" This punishment was called being "Shreked." While the computer-animated fairy tale adaptation was a long and troubled production, in the end, it ended up being a much bigger hit than "The Prince of Egypt."

There was almost a talking camel

One of the big ways "The Prince of Egypt" diverged from the formula of Disney and its imitators at other studios was in minimizing comedy and avoiding cute talking animal sidekicks entirely. It's not a humorless film, with Moses and Ramses' childhood troublemaking and the sleazy Egyptian priests voiced by Steve Martin and Martin Short provide some comic relief, but the general tone of the film is as serious as its heavy subject matter warrants.

Old habits, however, die hard, and with a crew of mostly Disney veterans, early drafts of the film had a bit more of the typical formula, including animal sidekicks. Chapman told Polygon, "The camel was supposed to be this big character" at one point in the production. According to Time Magazine, the camel was even supposed to talk! Wisely, the finished film avoided all talking animals, even though camels were still featured in the film.

Developing the voice of God

How do you cast the voice of God? "The Prince of Egypt" experimented with a few different approaches for how to handle the scene where God speaks to Moses at the burning bush. In a Los Angeles Times article published in April 1998 (eight months before the film's release), producer Penny Finkleman Cox explained, "The original vision was that God's voice was a compilation of all the people he ever cared about. But when we tried to execute that, we got the voice of Hal the computer." At this point late in the film's production, Finkleman Cox expressed an ambition to "remove the gender" from the voice of God.

Religious consultant Tzivia Schwartz-Getzug, however, vetoed the genderless approach, afraid some audiences would be offended by it (via Time). In the end, "The Prince of Egypt" ended up borrowing a page from DeMille's "The Ten Commandments." Like Heston did in that movie, Val Kilmer provided the voices of both Moses and God. In this presentation, God speaks back in the voice of whoever is speaking to God, a clever way to sidestep the issues of gendered voices while also allowing interesting psychoanalytical interpretations.

Avoiding DeMille's The Ten Commandments

No cinematic adaptation of the book of Exodus looms larger in popular culture than Cecil B. DeMille's 1956 film "The Ten Commandments." Starring Charlton Heston as Moses and Yul Brynner as Ramses, this four-hour Technicolor epic is among the biggest box office successes of all time after adjusting for inflation. Naturally, it was a reference point when Katzenberg and Spielberg first developed the idea for "The Prince of Egypt," but Katzenberg did not want his animated version to be a copy of DeMille's.

To avoid this direct influence, animators on "The Prince of Egypt" were advised not to watch "The Ten Commandments." As quoted in The New York Times, Katzenberg said, "I didn't want them intimidated because the images in that film are so powerful and so strong." Visual inspirations for the animated film were instead drawn from another classic desert epic, David Lean's 1962 masterpiece "Lawrence of Arabia," as well as from artists like Claude Monet and Gustave Dore.

Ofra Haza sang in almost every international dub

"The Prince of Egypt" had an unprecedented simultaneous international release on over 10,000 screens. "Nobody's ever opened in 85 percent of the world at the same time," Katzenberg bragged to The Washington Post. This meant the film had to be dubbed in many different languages with many different actors simultaneously, a big difference from Disney's strategy at the time of gradually rolling out dubs country by country. In almost all of those languages, however, one character would be voiced by the person.

Ofra Haza, the singer sometimes referred to as "the Israeli Madonna," played Moses' mother Yocheved in the original English recording and in 17 international dubs (via The Jerusalem Post). Some of these were languages she already spoke, while others she learned phonetically. Her role is small, but her section of the film's opening musical number, "Deliver Us," is so powerful that it makes sense why they wanted to include her singing for as many audiences as possible.

"When You Believe" was (possibly) a diva battle

One '90s Disney tradition carried over into "The Prince of Egypt" was that of having major pop stars record their own version of one of the film's original musical numbers to play over the credits, all the better for getting mainstream radio play. In the case of "The Prince of Egypt," this meant turning the film's Oscar-winning song "When You Believe" into a diva duet with Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey. Depending on what sources you believe, this meeting of megastars may have turned into a massive diva battle.

Houston and Carey both maintained that their collaboration was a purely positive experience and that reports of conflict were just ginned up by the media. "The Men Who Would Be King: An Almost Epic Tale of Moguls, Movies, and a Company Called DreamWorks" presents the media perspective as fact. Allegations include that Houston refused to leave her limo until Carey arrived, resulting in some very confused publicists, and that the two singers fought over who would receive the bigger dressing room.

Burger King promotions were nixed

Disney animated films rely heavily on merchandising for both promotion and profit. When making an expensive animated film like "The Prince of Egypt," the people at DreamWorks had to consider a similar merchandising blitz, but the sensitive religious subject matter made such matters difficult to figure out. Speaking to Time Magazine, Katzenberg listed off a bunch of ridiculous ideas for "Prince of Egypt" paraphernalia: "We came up with the Red Sea boogie board. We had the 40-years-in-the-desert water bottle. We had the parting-of-the-Red-Sea shower curtain."

While those specific examples might have jokes, the same article goes on to state that DreamWorks engaged in conversations with its licensing partners at Burger King that ultimately decided that fast food promotions would have been "a terrible disservice" to the film. This means someone actually suggested "Prince of Egypt" Burger King toys as a serious possibility at one point. Presumably the plague of cattle disease wasn't on the menu.

Three different soundtracks were released

If DreamWorks couldn't sell much in the way of "Prince of Egypt" toys, it could still hope to make a fortune selling soundtrack albums. DreamWorks Records went all out with three separate music releases tied to "The Prince of Egypt." "The Prince of Egypt: Music from the Original Motion Picture Soundtrack" was the traditional soundtrack album, featuring all of Stephen Schwartz's songs and Hans Zimmer's score as well as several additional pop covers and songs inspired by the movie.

The other two "soundtracks" released didn't actually have any music from the movie itself. "The Prince of Egypt (Inspirational)" featured gospel and other Christian music artists performing songs inspired by the movie and its Biblical source material. "The Prince of Egypt: Nashville" was also composed of original songs loosely connected to the movie, this time by country artists. The "Nashville" album ended up getting the most positive review of the three from AllMusic.

A stage version won a Grammy nom - and bad reviews

With music from Broadway composer Stephen Schwartz and heavy interest from religiously-oriented community theatre groups, it makes sense that DreamWorks Theatricals would eventually put together a live stage version of "The Prince of Egypt." The path to making the stage show, however, was incredibly troubled. The Bay Street Theater's 2016 concert performance was met with controversy over having mostly white actors playing the Hebrew and Egyptian characters (via The New York Times). Subsequent runs were cast more diversely, but the adaptation had other issues.

When it finally hit the West End in 2020, reviews were mixed, with flat-out pans from sources such as The Guardian and Broadway World. While the dance ensemble was highly praised, the adaptation's new songs were dismissed as unmemorable, the costumes as Vegas-level cheesy, and the script a downgrade from the movie. To make matters even worse, the show opened just six weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the entire West End, and it struggled to attract audiences after reopening in 2021 before eventually closing in January 2022.

The one upside to opening just before the pandemic shutdowns: an almost complete lack of competition for the best musical theater album Grammy award. This almost certainly helped the show's cast recording get nominated for the award in 2021 despite its high percentage of weaker songs. It ended up losing to the cast recording for the "Jagged Little Pill" Broadway musical.