The Untold Truth Of Death Wish

Death Wish tells the story of Paul Kersey, a mild-mannered architect turned cold-blooded vigilante after criminals murder his wife and rape his daughter. The 1974 drama offered one of the most unflinching looks at violence and retribution that had yet been put to film, and carried a message that the public at the time was all too ready to hear: that the only good crook was a dead crook, and if the police couldn't or wouldn't clean up the streets, perhaps average citizens should.

The film spawned four sequels, and while they didn't have quite the cultural impact of the original, Hollywood is rebooting the franchise a time when societal tensions in America are high. Before the new Death Wish arrives in theaters, it's worth taking another look at the source material—and one of the most brutal and controversial film series of all time.

The original film was based on a novel

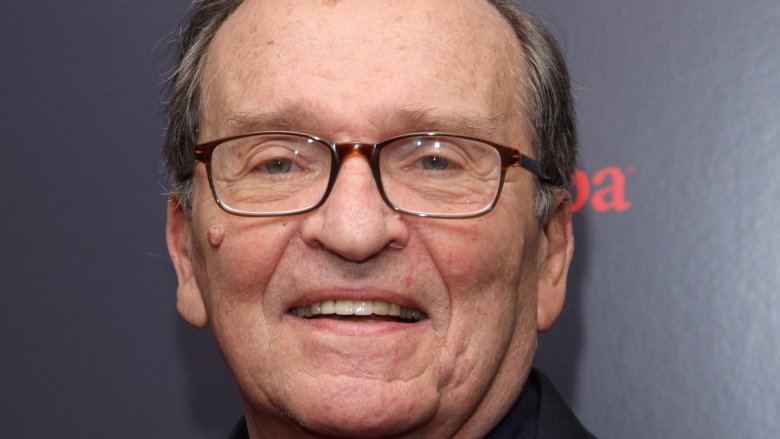

Brian Garfield was a successful author of crime novels and Westerns whose work shared a common thread: the emotional and psychological effects of sudden violence. The spark for his 1972 novel Death Wish was a real-life incident that took place while he was visiting his publisher in New York. "When I came out to get my car and drive home to the Delaware River, I found the top of my 10-year-old convertible slashed to ribbons," he later explained. During the cold and uncomfortable drive home, he caught himself fantasizing about wreaking violent vengence on whoever has vandalized his car.

Garfield's disgust with his own violent impulse drove him to create a character, named Paul Benjamin in the novel, through which he could explore his novel's central theme: whether violence is ever the answer, even when it seems justified, and the emotional consequences of vengeance. The book was a moderate success, but it would take a slight tweaking of these complex themes to turn its adaptation into a cultural icon.

New York City was terrifying then

No city symbolizes America quite like New York, and in the early 1970s, the Big Apple seemed to be rotting to its core. Some citizens felt like there was no safe place after dark—even Broadway theaters were known to push up their curtain times so patrons would have a better chance of getting home without getting mugged. Murders were on the rise, police corruption was rampant, street gangs ruled a virtually lawless Bronx, and every day seemed to bring a terrifying new headline.

With New York City as its setting, Garfield's novel might have seemed ripe for adaptation. But this was at a time when realistic depictions of violence were relatively new to the screen, and with real-life violence a constant fear for many, not everybody thought bringing Death Wish to theaters was a good idea.

Nobody wanted to touch the film

Garfield sold the rights to his novel to producers Hal Landers and Bobby Roberts, but passed on adapting the novel himself. Screenwriting duties went to Wendell Mayes, hot off the major box office success of The Poseidon Adventure, and Death Wish landed at United Artists with Sidney Lumet in talks to direct. Unfortunately, Lumet soon departed the production to make the classic cop corruption drama Serpico, leaving Death Wish with no director, no star, and an increasingly impatient studio.

In an attempt to shake up the production, Landers and Roberts were replaced with a new production team that included eventual director Michael Winner, who was known for gritty action films. But United Artists still considered dropping the project after several major stars passed on the lead role (Henry Fonda went so far as to call it "repulsive"). UA offered to let producers shop the project to other studios, which they did—only to be roundly rejected by every one.

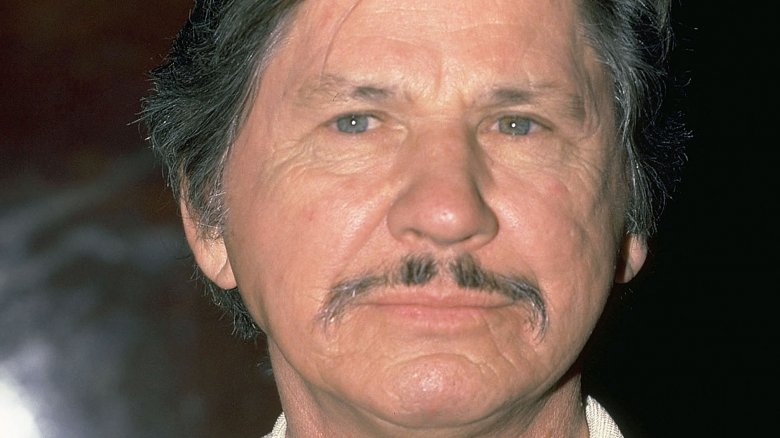

Winner solved the problem by casting Charles Bronson, a popular action star who was his star in three previous films, but United Artists remained unconvinced. The project might have sat in limbo forever had it not eventually gotten the attention of famed producer Dino De Laurentiis, who immediately saw its potential, acquired the rights from UA, and took the project to Paramount—where although they'd already rejected it twice, the third time proved to be the charm.

The novel's author disliked the film

The result was very different from the film Garfield had imagined. While remaining true to Mayes' script, which Garfield had been pleased with, Bronson's stony presence and Winner's tight, suspenseful direction created a visceral feel that compelled audiences to have rather the opposite reaction from the one intended by the novel. Rather than being shocked and appalled by Kersey's actions, they identified with him.

In a 2006 book about the making of the Death Wish series, the author condemned the film's message, which he said runs counter to the novel. "Because of the utter lack of subtlety with which it is filmed, it's an incendiary movie," he argued. "The book's cautionary message is that vigilantism may be a tempting fantasy, but it is a problem, not a solution." Garfield wrote his 1975 novel Death Sentence, in which Paul reconsiders his ways after inspiring copycats, as a response to the film. He has gone on record stating that he unreservedly hates all of its sequels, calling them "nothing more than vanity showcases for the very limited talents of Charles Bronson."

Reviews were mixed to negative

While some critics praised Death Wish on its technical merits, many were troubled by its moral stance, and some were outright hostile. Influential New York Times critic Vincent Canby offered withering scorn in his review, writing, "According to this film, (muggers) could be easily eliminated if every upright, middle-class, middle-aged citizen got himself a gun and used it at least three times a week." Calling it "a bird-brained movie to cheer the hearts of the far-right wing... so cannily fabricated that it sometimes succeeds in arousing the most primitive kind of anger," Canby dismissed it as "a despicable movie" that "raises complex questions in order to offer bigoted, frivolous, oversimplified answers."

Legendary critic Roger Ebert offered reserved praise while clearly being troubled. "The movie has an eerie kind of fascination," he admitted, "even though its message is scary." But the film's mixed-to-negative critical reception was obscured by its surprise box office success. In the first week of its New York run, playing in only two theaters, it grossed over $165,000—about $800,000 in today's dollars. As Paramount sank more money into promotion and pushed the film into wider release, national audiences followed suit, and the film went on to gross $22 million—equivalent to about $110 million today.

Sequels veered quickly into exploitation

While the first film contained a degree of nuance, its sequels abandoned all pretense of being anything but gut-level action thrillers. All four were produced by low-budget movie house Cannon Films, for whom "cheap and exploitative" constituted standard business practice. 1982's Death Wish II was basically a retelling of the same story with much more brutal violence, in which the wild-eyed craziness of Kersey's prey is ramped up to cartoonish levels, and Kersey himself casually tosses off one-liners before mercilessly dispatching hapless crooks.

Death Wish 3 (the series temporarily dropped the Roman numerals) featured such realistic depictions of street violence as Kersey literally shooting a single guy at point blank range with a rocket launcher, and Death Wish 4: The Crackdown used the real-life horror of the '80s crack epidemic as a backdrop for the heartless dispatching of cookie-cutter thugs. Nobody was paying much attention by the time a 73-year old Bronson saddled up for the final installment, 1994's Death Wish V: The Face of Death. Although nobody ever made a case for the Death Wish sequels as great cinema, some critics have gone a little further in their condemnation, making the case that the series advances a distinctly fascist worldview in its depiction of poor people as violent criminals who could probably all stand to be shot.

One sequel was caught up in a real-life vigilante case

In 1984, a shooting took place on a New York City subway train that shocked and captivated the nation. Feeling himself under threat by four young men asking him for money, Bernhard Goetz produced a pistol and shot and wounded all four, paralyzing one for life. Goetz was immediately dubbed the Death Wish Gunman by the New York Press, an association that would prove highly inconvenient for Cannon executives.

Producer Menahem Golan had struck a deal to shoot the third film on location in New York, but the production was forced to move to London as a result of publicity surrounding the Goetz incident. "We made a deal on the film a year ago, before Goetz shot those boys on the subway," Golan told the Chicago Tribune. "We felt the streets were available for another Death Wish movie. We are not social cleaners; we are filmmakers... if people insinuate that our movies influence people like Goetz, this is ridiculous. We are influenced by what goes on in the streets."

While this is a fair point, director Michael Winner didn't help matters by offering the incredibly insensitive quip, "I don't approve of what Mr. Goetz did, but I have to say, if he has to shoot anyway on the subway, I wish he'd do it in the week we're opening." Goetz was eventually cleared, but found liable in a civil case.

Bronson felt typecast by the role

Only a year after his star-making turn in the original Death Wish, Bronson confided to a Los Angeles Times interviewer: "I'm not a Charles Bronson fan... I don't think I turned out the way I thought I would turn out when I was a kid. It's a disappointment. I'm a disappointment to me. My image, my sound, everything else." It's a surprisingly forlorn statement from a man in the middle of a successful Hollywood career, but he would continue to periodically criticize his signature series, and his own image, for many years.

A decade later, he complained to the Tribune that Death Wish 3 contained too much over-the-top violence for his liking, while admitting that he felt pigeonholed in the role of Kersey. "Maybe I fit violence better on the screen. I don't know why, and I've stopped analyzing why," he shrugged. "I still feel trapped by it, but I have to go with it." Upon hearing that his star was trashing his new film, Winner was unsurprised, saying, "I've done six films with Charles (and he only liked one)... he was embarrassed by his screen presence."

It's already been remade twice... sort of

The Death Wish series spawned legions of imitators, and its DNA can be found in virtually every subsequen film featuring a wronged everyman with a gun. But in 2007, the vigilante subgenre looped back in on itself in a very strange way, as two quasi-remakes of the 1974 original were released to theaters within two weeks of each other.

The first, Death Sentence, is a loose adaptation of Brian Garfield's sequel to the original Death Wish novel. The Kevin Bacon vehicle distanced itself slightly from the source material by renaming its lead character and giving him a different backstory, but fans weren't fooled—only supremely confused when The Brave One, starring Jodie Foster as essentially a female version of Paul Kersey, was released two weekends later. Neither film was particularly well-received, but a decade afterwards, Hollywood is hoping we're ready for another helping of Kersey-style vigilante justice in the form of a straight remake of the first film.

The reboot continues the tradition of controversy

Director Eli Roth is no stranger to controversy and he knows his way around a violent setpiece, which just might make him the perfect choice to helm Paramount and MGM's rebooted Death Wish, starring Bruce Willis as Paul Kersey. But he had to hit back early and often at critics even before the film's release, as its first trailer rubbed a significant number of folks the wrong way at a time when the country is pretty seriously divided on issues like race and crime.

The trailer has been described as inappropriately action-packed and zany compared to the relatively sober tone of the original film, to say nothing of the source novel. It's also been suggested that this is due to obvious tone-deafness on the part of the filmmakers, as the imagery of an older white man indiscriminately gunning down random people of color has a specific context in 2017 that doesn't seem to have been taken into consideration. Reactions on Twitter have gone so far as to label the trailer "fascist propaganda" and "alt-right fan fiction," with one user musing, "Maybe #DeathWish isn't a good idea in a post-Trayvon Martin world. White dudes on vigilante rampages... (are) very 1980."

Then again, it wouldn't be a Death Wish film if it weren't steeped in controversy, so perhaps it's on the right track after all. We'll find out when it arrives in theaters on November 22, 2017.