The Worst Criminal In Law & Order: SVU Season 3

By its third season on NBC, "Law & Order: SVU" had found its voice, rhythm, and distinct approach to balancing the initial investigation portion of each episode with the latter half's trial element. It had also begun portraying more uniquely appalling, sensational, and personally-motivated crimes. From the identity-crisis-driven racist and murderer of "Inheritance" to the psychopath-in-training of "Prodigy," the season delved deeper into the psychological mechanics of its offenders, often with the help of BD Wong's Dr. George Huang. As a result, Season 3 put forth some of the earlier years' most devastating criminal acts and suspects, all while introducing audiences to several psych-based defense strategies, including one that viewers would grow ever more familiar with over the course of the next twenty seasons: Extreme Emotional Distress.

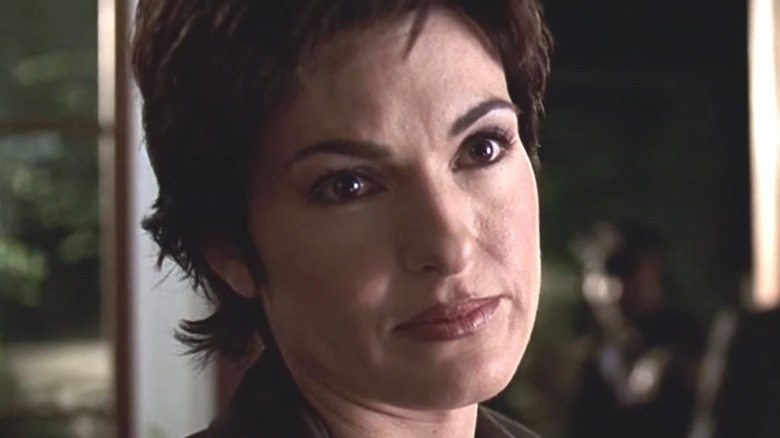

This defense is employed by a distinctly disturbing criminal in Season 3, but it's a combination of factors that make them one of the most memorable killers on the show. In the episode, A-list guest star John Ritter plays a husband whose feelings of inadequacy and possession over his own wife lead him to commit a shocking crime, one for which he not only feels zero remorse but is convinced he was well within his rights to perpetrate.

What's worse, his experience as a psychiatrist along with his medical training allows him to construct a convincing defense — one that gives A.D.A. Alex Cabot (Stephanie March) a run for her money, and brings up complicated questions about the definition of murder.

John Ritter is the husband from hell in Monogamy

In Season 3, Episode 11, after learning that his wife is pregnant with what he believes is her lover's baby, Dr. Richard Manning (John Ritter) attacks his wife in an alley, performs an amateur C-section that nearly kills her and succeeds in leaving her infertile, and murders the (supposedly) unborn fetus. Though we'll later learn Manning's victim actually took a breath outside the womb prior to being killed, the case is complicated by the fact that Alex Cabot can't charge Manning with murder, since doing so would suggest that legally, an unborn fetus has the same rights as a human. In other words, charging Manning with murder would mean setting reproductive rights issues back decades, despite the fact that this particular procedure was obviously not the mother's choice.

Not only does Manning know this, he also knows that it will be medically impossible for the medical examiner Dr. Melinda Warner (Tamara Tunie) to prove that the fetus was alive and living outside of the womb at the time of its death. Thus, he's able to commit the violent crime with a cool, committed confidence that makes his matter-of-fact explanation of the event all the more chilling. What's more, as a psychiatrist, he knows all the right words to say to convince the court that he was under extreme emotional distress at the time of assault, despite the fact that it was clearly premeditated.

Ritter's Manning is a new kind of criminal

Importantly, Dr. Richard Manning isn't a victim of abuse, or an individual born with a psychological condition that prevents him from being able to distinguish right from wrong. On the contrary, he's a successful psychiatrist who quite simply believes that he owns his family, and that his actions were a logical means of keeping that family intact.

In some ways, Manning is a variation on the classic family annihilator, one who sees his crime as both rational and righteous. John Ritter's portrayal of the character — one of the best guest star performances in the series, according to several fans on Reddit — only adds to his despicableness. In his initial confession to detectives, he comes across as borderline delighted by his crime.

Ultimately, the universe hands Manning some semblance of justice. When a DNA test reveals that it was Manning who fathered the deceased infant, he finally demonstrates some kind of remorse. It's the nature of this remorse, however, that makes Manning even more grotesque that initially assumed. He isn't sorry about what he did to his wife and child, he's only sorry that it was his child, and not someone else's, who died. Once again, his obsession with ownership and control supersedes all else. Finally, the fact that Manning's profession puts him in charge of the mental well being of vulnerable patients puts him even further over-the-top. Who's to say how many men came to him battling feelings of inadequacy, or how many families he ruined by offering advice born of his own twisted pathology?

If you or someone you know is dealing with domestic abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.