How Does The Original Carrie Differ From The Book?

It's a question as old as the first adapted screenplay: which did you like better, the movie or the book? With both the film and novel of "Carrie," this question is especially difficult. The book "Carrie", published in 1974, was Stephen King's debut novel, and it went on to sell over four million copies and earn a spot on the 100 most banned books between 1990 and 2000 (per The American Library Association). The 1976 movie was a similar hit, earning nearly 34 million at the box office, two Oscar nominations, and an undeniable spot in the horror movie hall of fame.

If you ask Stephen King, he'd say Brian De Palma's movie was a better interpretation of his work, as he did to Playboy Magazine when he called the film "far more stylish than my book." If you ask us, they're both great (certainly better than the musical). Everyone has their own take, so a better question is: what's the difference between the book and movie anyway? Unlike questions of taste, this is one we can answer definitively.

For instance, did you know Carrie looks completely different in the book from how Sissy Spacek did in the film? Or have you ever wondered what happens to Sue Snell after the horrifying conclusion to the film? Is that horrifying conclusion even the same in the book? Well, prom-goers, we have answers. And, of course, beware of major spoilers ahead.

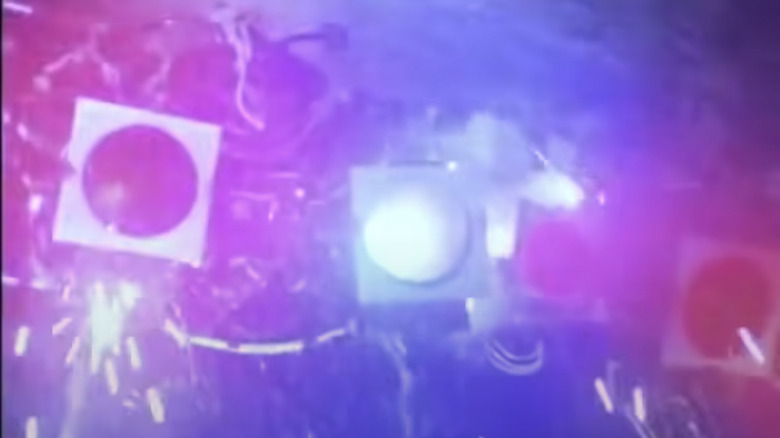

One of these proms is not like the other

The prom scene in the movie version of "Carrie" is a tour de force in stylistic filmmaking from the moment the blood bucket drops. Prom-goers jeer but we don't hear their laughter, the sound returns and Carrie's sight turns kaleidoscopic, and finally, the screen splits and the mayhem begins.The actors especially wanted to sell this scene. Sissy Spacek was so committed that she didn't wash the fake blood off for three days of shooting. Actress P.J. Soles, who played Norma Watson, got sprayed with an actual fire hose — no stunt double required (per Vulture).

In the book, Carrie's prom meltdown doesn't take center stage in the same way. It's more the kindling that starts an even greater fire. Rather than lashing out immediately, Carrie runs out of the gym before returning to attack her classmates. The scene is much more brutal, too. Carrie electrocutes the other students, starts a fire, then opens all the hydrants around the school to stymie the fire department's rescue efforts. She then goes on a psychic rampage — detonating the town's gas main and razing half the real estate.

A notable similarity between the two versions, however, is how Carrie gradually becomes more violent. At first, it seems Carrie just wants to get back at her classmates. In the book, she thinks to herself that she'll just get them wet with the sprinklers. In the movie, the electrocution seems an unlucky accident, but in both cases, her anger spirals out of control, and her retribution turns homicidal.

Was Sissy Spacek too pretty?

"Carrie" has often been called a Cinderella story, and with good reason: evil mother, magic powers, a big ball at the end. But before Cinderella can be the most beautiful girl at the ball, she has to be the homely, maltreated step-daughter covered in cinder ash. The book leans into this aspect of the fairy tale heavily.

The Carrie of the book is a big, acne-ridden girl who is narratively associated with farm animals (hence pig's blood in the bucket). In the principal's office, Carrie stares off into space in a way described as "bovine." However, over the course of the novel her looks are judged less harshly, as she grows more confident in herself. And, just like in the movie, her prom date, Tommy, calls her beautiful and means it. Likewise, Carrie's mother, Margaret, is more imposing in the text. She works as a speed ironer, and has bulky arms and a large square frame as a result.

Let's be real: Sissy Spacek and Piper Laurie don't look like that. Both actresses are rather slim in the movie, and Piper Laurie certainly doesn't seem as physically imposing as the Margaret of the book. Spacek actually acknowledged the difference between the Carrie of the book and her film portrayal to Coming Soon: "[Carrie] was such a loser and I ... gave the character a little bit of hope."

Carrie and Momma get stoned

Not in the way you're thinking, though. In the book, Carrie telekinetically rains down stones and hail from the sky and through her roof. Why did Carrie bombard her house with her and her mother still inside? Because her mother was trying to gouge her eyes out with a butcher's knife, naturally.

To try and make sense of Margaret White's zealous rage, you need more context. Margaret — who Carrie calls "Momma" — caught Carrie outside staring at their neighbor, a teenage girl who was sunbathing in a scanty white two-piece. Margaret's religious extremism centers on a fear of sexuality; to her, nothing is more sinful than a woman revealing herself. When she sees Carrie talking with the neighbor, it sets her off. She threatens the young Carrie with a knife. To save herself from her crazed mother, Carrie nearly destroys their home in a psychic burst. Afterward, Carrie forgets about her telekinetic powers until much later in the book, when puberty hits.

This scene was so important to the text that it actually begins the book. Before readers meet Carrie, they see a news clipping that covers the strange incident in a local Maine paper. Given its significance structurally and narratively, it's surprising that the stoning incident is completely absent from the film. Even more surprising is that it's the first scene in the script. Brian De Palma, the film's director, must have decided it clashed with his vision. At least you can see it in the 2002 and 2013 remakes.

Carrie versus Momma

One of the broad-stroke differences between the book and the movie is that the book is typically more violent than the movie, and that violence is more brutal. The final confrontation between Carrie and her mother is one notable difference. In the book, the scene is efficient and simple; in the movie, their last meeting is the climactic moment.

After razing the town, in the novel, Carrie returns home to find her momma waiting for her in the kitchen. Margaret holds a newly-sharpened butcher knife, which she reveals to Carrie. Despite the threat, Carrie falls before her mother, as if in prayer. Then, Margaret buries the butcher's knife in Carrie's shoulder, and Carrie uses her telekinesis to stop Margaret's heart. The house remains standing, and Carrie leaves, the novel's climax still a few scenes away.

Their cinematic confrontation is much more dramatic. Carrie returns home directly from prom, no ravaging of the town. She takes a bath. Everything calms down. Then Carrie seeks comfort from her mother, and Margaret, the betrayer, literally stabs Carrie in the back. Carrie tumbles down the stairs into the kitchen. Margaret follows, and Carrie pegs her mother to the door frame and telekinetically stabs her with a dozen knives. Margaret dies in a position that mirrors the Saint Sebastian statue in Carrie's "closet."

Finally, in a psychic flurry, the house collapses in on itself, burying Carrie and her mother both. It's arguably a more poetic ending than the book's, but Stephen King isn't known for his endings anyway.

Chris and Bobby were worse in the book

Chris Hargensen and Bobby Nolan of the "Carrie" movie are more imps than devils. Chris is a mean girl who gets banned from prom for harassing Carrie and skipping detention; Bobby Nolan is her idiot henchman. Just look at this scene where John Travolta plays Billy drinking and driving. He's less a monster than a dumber, meaner Danny Zuko. Similarly, Chris comes off as more vain than evil.

Of course, they aren't blameless. Billy is all too excited to bludgeon a pig to death. Chris pulls the rope that douses Carrie in blood. There are hints of something malicious within them. In the end, that evil is realized when they try to run over Carrie, and she sends them cartwheeling to their death. Until then, though, they almost seem like pranksters in over their heads.

In the book, Chris and Billy are devils all the way. Before showering Carrie at prom, Billy tells Chris that what they're doing is assault, and both are all too willing to continue. Billy especially is more vicious in the text, as he's far more abusive to Chris in the text than in the movie. Where movie-Billy slaps Chris a few times in anger, book-Billy outright assaults her after they learn the town was razed. Their deaths are similar though: Carrie telekinetically drives them into the side of a bar.

One can't help but sympathize with Chris in the book. Maybe that's why De Palma toned down Billy's aggression on camera.

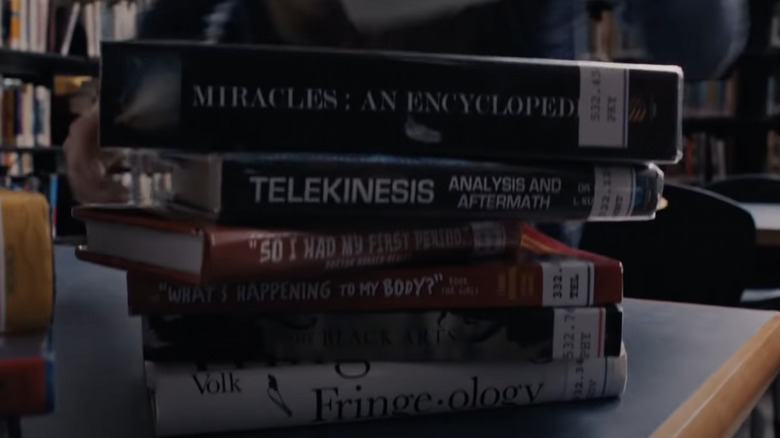

Carrie was flexing in the text

Dwayne Johnson once said, "Put in the work, put in the hours, and take what's ours." Carrie definitely listened, at least in the book. Unlike her movie counterpart, book-Carrie practiced and honed her telekinetic abilities. Thus, readers aren't shocked when she is able to destroy the town with her mind in the finale, at least not shocked she had the capability to do it.

In the text, Carrie describes the feeling of using telekinesis as a sort of internal flexing. In fact, the word "FLEX" appears in the narration to indicate Carrie reaching out with her mind. Days before the prom, Carrie tests her newfound powers by lifting her bedroom furniture off the ground and placing it gently back down. These mental reps get easier and easier, until she lifts them all into the air at once, with little strain. Later, when Carrie pops open hydrants and tears down power lines, the progression feels earned.

Carrie also has a telepathic ability in the book that is never seen in the film. As she destroys the town, various residents, who never met Carrie before, inexplicably know who she is and how upset she is just by standing near her. Carrie's telepathic influence is so great that Sue Snell is able to find her in the novel's conclusion, where she and Carrie experience a terrifying telepathic link.

The book has a different timeline

Something you get in a book that you don't quite get in a movie is narration. Sure, characters will occasionally provide voice-over narration, but the camera is the primary narrator — and this narrator has limits.

Books have a lot more temporal liberty. While walking back home after the locker room debacle, Carrie thinks back on the past, and readers are instantly transported. When the narration introduces an Esquire interview from 1980, at least a decade after Carrie's high school prom, the reader understands that they've been taken to the future. There are exceptions, but usually, a movie's camera operates in the present tense.

"Carrie" is an epistolary novel. Coming from the Latin word for letter, this genre has its roots in stories told entirely through exchanges of letters, and has since broadened to include any story that uses documents to convey narrative. For example, Jennifer Egan's "A Visit From the Goon Squad," narrates almost half the book via powerpoint presentation (per The Guardian). In the case of "Carrie," these documents are excerpts from books, magazine interviews, letters, and even state testimony. Notably, all these documents are created in the narrative future, after Carrie dies.

It would have been interesting to see De Palma include these epistles in the movie somehow; however, they are a great reason to go read the book. But there must be something you get in films that you don't really get in books, right? Perhaps, visual easter eggs?

Carrie is a scientific marvel

The book version of "Carrie" never references any real texts, unlike the movie. But the documents that are referenced persist throughout the novel's narrative, and they aren't just single-use. One document, in particular, gets excerpted again and again in the book. This meta-text is an imaginary essay called "The Shadow Exploded: Documented Facts and Specific Conclusions Derived from the Case of Carietta White."

Stephen King likely included this document to spice up his exposition. Rather than explaining within the main narrative that Carrie has telekinesis, it's more interesting to show the scientific discourse around Carrie's abilities after she already destroyed her entire town with them. Plus, it builds suspense toward the foreshadowed horrific finale. There's even a miniature conflict within these future narratives: The Shadow Exploded references other essays written after Carrie's rampage that try to dismiss her psychic powers.

One quirky and extraneous bit from "The Shadow Exploded" concerns the genetic disposition toward telekinesis. The "TK Gene," as it is referred to in the meta-text, is a recessive gene that only manifests if both parents are carriers and if the offspring is a girl. It's described as a sort of inverse to hemophilia, which is similarly recessive, but only manifests in disease if the offspring is a boy (although this metaphor was an inaccuracy on King's part). While they serve little narrative purpose, it's the idiosyncrasies like these that make the book a worthwhile project, even if you've already seen the movie.

The White Commission

When it isn't a high school horror, the book is a political thriller, at least in its future narrative. After Carrie destroys the town, the state of Maine creates an investigatory committee to get to the bottom of the whole affair. This group and their investigation are known within the text as The White Commission, and they aren't playing around.

Although it's referenced prior, The White Commission primarily enters the narrative once Carrie begins wrecking the town. In between the primary narration of the mayhem, King interspersed testimonials from the Commission. These testimonials are given by a laborer who sees Carrie ignite the high school and break the nearby fire hydrants, a mother a prom-goer who watched as Carrie exited a church and attacked her and others with high tension wires, and Sue Snell.

Sue Snell is, of course, the girl who asked her boyfriend to take Carrie to prom. She seems to be the only one of the girls who genuinely regrets harassing Carrie. That's why it's so tragic and frustrating to read The White Commission's attempt at scapegoating her. The Commission believed Sue was in on the bucket prank and only asked her boyfriend to go to prom with Carrie as bait.It's unclear if Sue receives any punishment from the Commission, but it's made quite clear from other meta-texts — especially "The Shadow Exploded" — that the Commission tried to downplay Carrie's powers.

Brian De Palma, why is all this political drama missing from the movie?

Desjardin? Don't you mean Miss Collins?

As previously mentioned, "Carrie" is a twisted Cinderella story. In the film adaptation, De Palma realized this fairy tale allegory was missing one thing: the fairy godmother. So, he rebranded the gym teacher from the novel, Rita Desjardin, into Miss Collins. Sshe's the only adult in Carrie's life who seems to truly care for her.

From the moment she walks into the locker room, Miss Collins is trying to pull Carrie out of the coals. She cleans her up and spends the rest of the movie looking after her. She even doles out severe punishments to the girls who harassed her in the locker room — unknowingly causing the chain of events that led to Carrie getting pig blood dumped on her at prom. All Miss Collins wanted to do was help Carrie, but instead, she dies at prom by Carrie's own hand.

The book is a slightly different story. Miss Desjardin is sympathetic to Carrie, like Miss Collins, but we get a peek straight into her head. Desjardin always resented Carrie a little bit, just like all the other girls. Still, after the fiasco in the locker room showers, Desjardin also harshly reprimands the other girls. However, she doesn't lay on Carrie's praises as thickly as Miss Collins, and better yet, she escapes the prom alive. In one of the novel's final documents, Desjardin resigns from her teaching post. After all the hell she had a hand in, who can blame her?

De Palma cut some unnecessary characters

Another difference between books and movies: books are longer. The movie "Carrie" has a 96 minute run-time. "Carrie," the book, is about 200 pages, depending on the edition. If you read at the steady clip of a page per minute, it will still take about twice as long to finish the book as watch the movie. With that much content to cut for the movie, some big things were going to be left out, even entire characters. In "Carrie's" case, there were two.

In the movie, Principal Morton is the only principal in the school, and he's bad with names. In the book, Morton is the vice principal — also bad with names — to Principal Grayle, who is depicted as a steadfast, if nervous, leader of the school. Along with Grayle, the film cut Chris Hargensen's father, a lawyer who dukes it out with Grayle.

When Chris's father visits Grayle, he comes with hefty demands: let my daughter go to prom and fire the gym teacher. A miniature court drama follows, wherein Grayle defends the school's decisions and sends Mr. Hargensen away with his tail between his legs.

Grayle and Miss Desjardin together give a different impression of the school than the movie's counterparts. Both make clear efforts to defend Carrie from the children who torment her. Their efforts prove ineffectual, of course. After Carrie's rampage, Principal Grayle, like Desjardin, resigns. Chris's father is never heard from again. Neither is Chris, for that matter.

Carrie's final moments

As mentioned above, Stephen King has been said to struggle with endings. The ending to the book version of "Carrie" is by no means poor storytelling, but De Palma may have a leg up. In a Turner Classic Movies program, King said of De Palma's ending: "We have a monster hit on our hands and Brian De Palma has done something new."

From the moment Carrie returns home, De Palma veers from King's source material. Carrie and her mom die together in the movie as their home collapses — a fitting end to their tumultuous relationship. Then follows Sue Snell's dream sequence where she visits the site where the house once stood, lays down flowers, and Carrie's bloodied arm grabs her from under the earth. While different, this final scene resonates with Sue's final interaction with Carrie in the book.

After killing Chris and Billy, Carrie is bleeding out in the parking lot of a roadhouse. Following Carrie's telepathic influence, Sue Snell is able to retrace Carrie's steps to the lot. There, Carrie accuses Sue of being in on the bucket prank. To prove her innocence, Sue tells Carrie to search her mind for the truth. The mind-reading is incredibly invasive, but Carrie realizes Sue had no ill intent. A part of Carrie seems trapped in Sue's mind, though, and Sue is forced to telepathically experience Carrie's death alongside her. In the end, it seems both versions of Sue will be forever haunted by Carrie White.

Lightning round

All these major differences account for only a fraction of the things that got lost in adaptation. So, to close out, here's a lightning round of the many minute, but notable, differences between the "Carrie" film and novel.

The Principal Norton of the book was a bit of an oddball. He's described as having a John Wayne complex and has an ashtray shaped like Rodin's "The Thinker." In both versions, Carrie telepathically knocks it over, but in the movie, it's a regular old circle.

Adorning Carrie's dining room wall in the movie is a massive rendition of "The Last Supper." While there are many religious artifacts in the book's house, it lacks this picture as well as the Saint Sebastian statue in Carrie's "closet."

Before Carrie has her first period, she mistakes the purpose of tampons. One of her classmates in the book recalls seeing Carrie attempt to use a tampon as a blotter for her lipstick.

Unlike in the film, Tommy's prom-posal to Carrie wasn't much of a hassle. Carrie was skeptical at first, but she accepted once he persisted.

The iconic bucket that douses Carrie and Tommy in the movie is actually two buckets in the book, one for each of them. Also, Billy rigs up the buckets all by himself, and the setup is more elaborate.

The king and queen vote goes differently at prom. There's a tie, and Carrie and Tommy win the run-off. Chris still cheats the votes, though.

And that's "Carrie" in a jiffy.