Things In WALL-E That You Only Notice As An Adult

2008's "WALL-E" was a hit with critics and audiences alike, fitting into the run of successful movies for Pixar Studios so well that you kind of forget it's about the total ruination of the planet. After eight movies with kid-friendly premises like toys that come to life, a family of superheroes, and an unlikely rat chef, Pixar was so confident in its storytelling that it bet a simple love story between two robots would distract you from the idea that not only did humanity make its own planet too toxic to live on, it survives only in atrophied blob-like form on interstellar cruise liners. And they were right, because we loved "WALL-E," despite its chilling implications.

As time goes on, though, we might feel a little differently about a parable set long after doomsday, no matter how adorable. In retrospect, it's also fascinating how many strange and unnerving implications "WALL-E" has about the nature of humanity, artificial intelligence, capitalism, and the intractability of climate change. It's a movie with a timeless and simple love story, set in a context that gets more terrifyingly relevant by the year. These are the things about "WALL-E" only adults notice.

The premise keeps hitting closer to home

2008, in retrospect, was a simpler time. It was only two years after the documentary "An Inconvenient Truth" began to really spread awareness of the threat that global warming posed to the planet, and the more broadly sinister blanket term "climate change" was hardly in the news at all. The ensuing 14 years have seen an increasing number of wildfires, record-setting temperatures at various points all over the world, polar vortexes, unusually active hurricane seasons, and countless other disasters of various sizes that are all attributable to climate change.

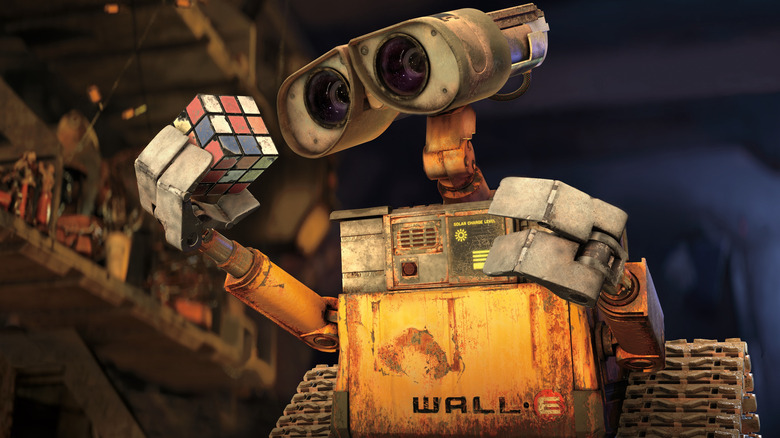

"WALL-E" is almost quaint in representing the harm that we've done to the planet with a kind of brownish haze, but mostly with vast, absurd amounts of trash. Our small, resolute Waste Allocation Load Lifter Earth-Class robot has apparently spent centuries packing refuse into cubes in what seems like an apt visual metaphor. But even though we aren't yet piling garbage so high it towers over skyscrapers, trash is a big part of the climate crisis in reality as well: landfills will account for 10% of greenhouse gas emissions by 2025, in addition to causing a host of other environmental issues. The backdrop of "WALL-E" was already one of the most chilling and relevant settings for any kids movie, and it becomes more chilling and more relevant with each passing year.

WALL-E's plight is devastatingly sad

Even if you summon the will to set the reality of climate concerns aside and just let "WALL-E" cast its spell, the central premise is almost unbearably sad. WALL-E, a small robot whose sole purpose is to condense waste into neatly stacked cubes, has been laboring for around 700 years on the deserted planet Earth, with only a cockroach and a trailer full of junk for company. The opening scenes of the movie are set to a jaunty show tune and mine some humor out of WALL-E's confused reaction to recognizable everyday objects, but if you actually stop and think about WALL-E's life, it's a particularly maudlin way for the film to begin.

Fortunately, "WALL-E" only takes us through one day in the life of its impossibly lonely protagonist before a mysterious rocket lands and the real adventure begins. But for the first twenty minutes or so, kids and adults alike are invited to contemplate solitude and futility in Pixar's bleakest opening so far.

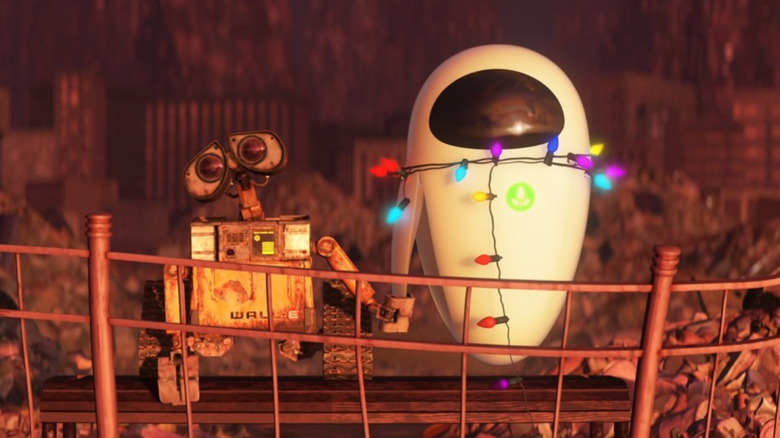

WALL-E borrows its emotion from Hello, Dolly!

Not only does "WALL-E" have a premise that's both horrifically sad and unnervingly environmentally relevant, it's also largely about two robots that only say a half-dozen words or so between them. It's amazing, when you think about it, that audiences were able to connect with the story emotionally, and it's actually thanks in large part to songs from the 1969 movie musical "Hello, Dolly!" WALL-E has managed to find a VHS copy of the film that improbably still works, and repeated clips of just two songs serve as emotion shorthand at several different points of the story.

The jaunty, peppy "Put On Your Sunday Clothes" serves as the enervating, ironic choice to open the movie as we zoom in on the polluted, empty Earth, and then goes on to be a theme song for both WALL-E's curiosity and optimism, as well as a rallying cry for his robot brethren aboard the Axiom. Meanwhile, "It Only Takes A Moment" is the theme song for WALL-E and EVE's romantic connection. There's also a scene set to "La Vie En Rose" by Louis Armstrong, who was also part of "Hello, Dolly!" Between lifting the moods of an old musical and Thomas Newman's subtle, wonderful score, revisiting "WALL-E" as an adult really makes you consider how much music can accomplish in a nearly wordless film.

The story is a parable about capitalism

In the future of "WALL-E," the corporation Buy N Large is indistinguishable from the government. CEO Shelby Forthright, played in a few scenes by Fred Willard in the only live-action role in any Pixar film, speaks from a podium in front of a blue backdrop that looks a lot like the White House, and Buy N Large seems to be solely responsible for "Operation Cleanup," the plan to save the Earth while humanity is off on luxury space cruise ships. It's something that initially seems darkly ironic and silly, but has grim and sinister implications that only get more uncomfortable for those of us who've aged through major recessions and government malfeasance from both parties over the years.

You'd think that Disney, who bought Pixar just a couple years before "WALL-E" was released, wouldn't want to pull the thread on how giant mega-conglomerates are (a) insidiously tied to government and also (b) leading us down a ruinous environmental path. Of course, this was before Disney went on to acquire Marvel Studios, Lucasfilm, and 20th Century Fox, so it wasn't as on the nose at the time as it seems today, but it's still strange, in retrospect, how the general theme of "WALL-E" seems to be "stop being such a consumer, even though this movie is a commercial product from one of the biggest companies ever known."

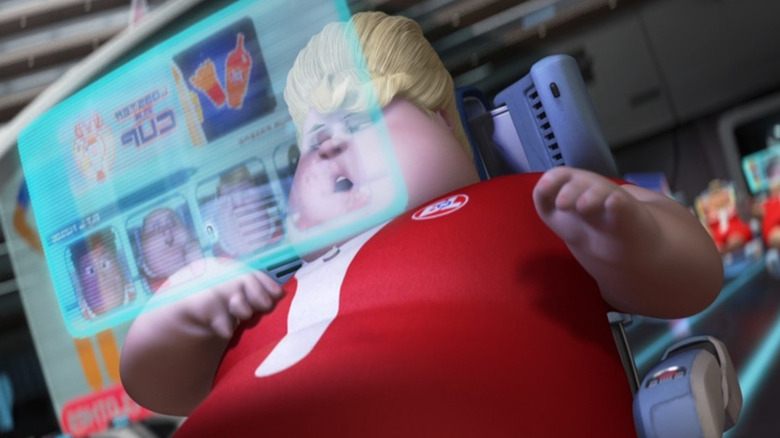

We basically live on the Axiom already

Another thing that's hard to remember about 2008 is that screens weren't as dominant a force in our lives at the time. Most phones were still of the flip variety, or at worst Blackberries — definitely nothing as entrancing as modern-day smartphones with their endless apps, games, and demands on our attention. Netflix had just barely introduced its streaming service, so YouTube was the only real video streaming option, with barely a fraction of the content that it has today. As the years have gone on, streaming became ubiquitous, and as many of us became awkwardly aware during the COVID-19 pandemic, if we're not careful and intentional about our screentime habits, we basically already live on a planet-sized version of the Axiom.

Most chillingly, especially after the mass movement to remote work after the coronavirus, "WALL-E" characters are even seen using a Zoom-like interface in their hoverchair displays to talk to one another, instead of just going to find one another somewhere on the ship. We've got screens in our cars now, screens on our appliances, and screens on our wristwatches. Devices are getting so "smart" that it will be the challenge of modern humanity to remember we're on a planet and not a spaceship, and "WALL-E" is a great cautionary tale to remind us.

How are babies made on the Axiom?

It's only through WALL-E's chaotic influence that we see two humans on the Axiom, Mary and John, start to interact with one another and accidentally hold hands. The novelty of it shines on their delighted, bashful faces — and for adult viewers, an unsettling thought comes crashing in to undercut it: If that's where people are in the future, relationship-wise, how have new babies been born on the Axiom for the last 700 years? We distinctly see a group of toddlers being taught by robots in a day care earlier in the film, but given that we also see the captain of the Axiom struggling to walk in a later scene, it's a safe bet nobody on the ship is doing anything more strenuous.

The implication is obviously that somewhere on the ship there's a place where, like "The Matrix," humans are grown instead of born. How the machines on the ship make this happen, we can only imagine. "WALL-E" is largely an allegory, and there are lots of things we don't learn about the rhythms of life on the Axiom (there also don't seem to be too many elderly people, come to think of it). But showing us a group of babies specifically makes wondering how basic reproduction works unavoidable, and unavoidably unsettling.

WALL-E has a dim view of human nature

In giving most of the agency in the story to WALL-E and EVE, "WALL-E" presents a depressingly negative view of human nature. With every need taken care of, on an apparently endless cruise to wait out Earth's cleanup, humans on the Axiom have done ... nothing. For seven centuries, they eat food, talk to one another on screens, watch stuff, and ride their hoverchairs listlessly about the ship. This depiction of humanity is wildly fat-shaming in that is uses the rotund shapes of our descendants for several punchlines, but it also contains a sad and cynical argument about the nature of humanity.

If all of our needs were met, if we had no reason to work, "WALL-E" thinks that we would just ... sit there. Doing nothing. It's a view of humanity that suggests we're nothing but consumers, entranced by food and screens like voluntary participants in a prison we could leave at any point. It's a huge bummer, and it muddles the film's anti-consumerist message.

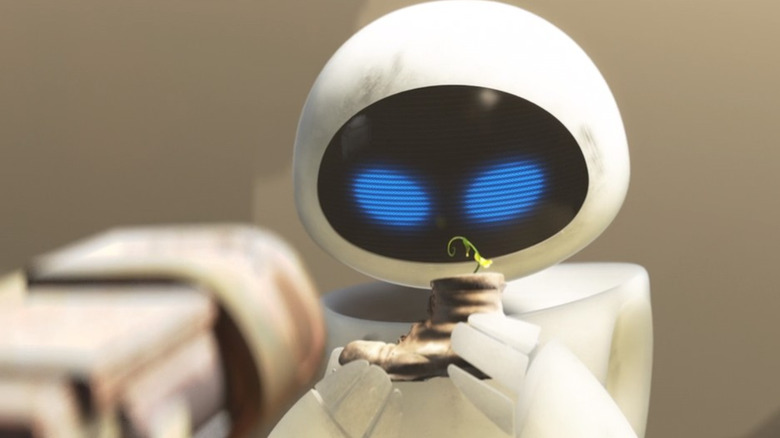

EVE throwing the plant aside rings hollow

"WALL-E" lives and dies on the simple, charming love story between WALL-E and EVE. It's not explicit, but WALL-E is clearly coded as male and EVE female, which is fine for anthropomorphization purposes, and EVE's role as the more action-oriented and competent of the pair defies lazy gender stereotypes we've seen in many other kids' movies. In fact, despite nominally being the hero of the story, WALL-E is also the "damsel in distress" that EVE needs to rescue at several points.

There's one moment, though, two-thirds of the way through the movie, that stands out as a little false when you take an adult, analytical lens to it. After AUTO, the evil ship's autopilot, damages WALL-E and he falls down the trash chute, EVE goes to save him from being airlocked out into space. In her focus on trying to fix WALL-E, she throws aside the vital plant that represents evidence that Earth is healing and humans can safely return, even when WALL-E reminds her of her "directive." Granted, the moment does come just after she's seen how WALL-E took care of her on Earth when she was in lockdown, but it's an abrupt abandoning of her mission that goes against the EVE that we've come to know and respect for her no-nonsense dedication.

WALL-E is super casual about desecrating other WALL-Es

"WALL-E" strikes a carefully calculated balance, in that it relies on children and adults personifying and identifying with WALL-E enough that they're not thinking too hard about the environmental implications or the calamitous end of society. And it works remarkably well ... except for how cavalierly WALL-E scavenges parts from dead robots that look exactly like himself to stay in good repair. First, he pauses by the "corpse" of a different WALL-E unit to desecrate it by stealing its tread. Not too long afterward, when EVE damages one of his "eyes," he casually reveals he has an entire shelf of discarded WALL-E parts to choose from to replace it.

It's a strange cognitive dissonance. In the emotional climax of the movie, after WALL-E has been so damaged that EVE has to replace several more parts and an internal circuit board, we're left in doubt for a moment that WALL-E even remembers her, as he may be a sort of undead Frankenstein's monster of other dead WALL-Es with no memory. It turns out okay, but only if you're willing to ignore WALL-E's strange sort of robot cannibalism.

What's WALL-E's call to action?

As discussed, there's so much "WALL-E" doesn't want you to think about that it's hard to be left with any sort of moral lesson or spiritual takeaway. Children's movies aren't obligated to have one, of course, but they almost always have some sort of "just be yourself" message that you can leave the theater with. "WALL-E" has a vague theme about the difference between "surviving" and "living," but it's hard to really connect it to anything in particular since its robotic protagonists aren't terribly invested in the fate of humanity and Earth.

Obviously we shouldn't let the planet drown in garbage or the atmosphere become entirely toxic, but what would "WALL-E" have us do to avoid it? As the intervening years have led to us to realize, the damage from climate change is so far reaching, and has been tied to our technology for so long, that it's baffling to know where to start as an individual. Other than a vague resolution to avoid so much screentime and not be a passenger on the proverbial Axiom of the internet, there's not much "WALL-E" leaves you with other than a warm feeling for cute robots.

This was the best plan humanity could think of?

The technology we see depicted in "WALL-E," which was all apparently made around 2100 when the Earth become uninhabitable, includes spaceships that are still running perfectly after several hundred years, food replicators that feed the entire ship's population to excess, an endless array of robots that serve every conceivable function, and hyperspace technology that gets the Axiom back to Earth in a matter of seconds.

So with all of this tech at its disposal, the best plan that humanity's corporate overlords could conceive of was to leave a bunch of trash-scooping robots behind and try to wait the crisis out on a cruise? Why not use the hyperspace tech to try to find other planets to colonize? Why aren't there robots designed to scrub carbon from the atmosphere? Why not shoot all the garbage on Earth into the sun? There is perhaps an intentionally cynical message in Buy N Large's plan to sell humans on a cruise to distract them from the devastation that their own consumerism has wrought, but it seems like finding a more efficient solution would be good for the company's bottom line, as well.

WALL-E's true greatness is its lack of dialogue

The thing that really makes "WALL-E" great, despite all of the depressingly realistic concerns it raises about our present and future, is that the movie barely actually talks about those concerns. The opening half is almost a Chaplin-esque silent comedy as we watch our plucky and curious hero fill the time, and it becomes a breathless adventure when EVE shows up to shake him from his routine. The music, score, and Pixar's reliably beautiful animation make "WALL-E" a singular film — there's nothing else like it.

Eventually, after repeated viewings, you start to recognize every little mumble and jittery noise that WALL-E makes as an extension of his personality. Dialogue forms the backbone of most movies — it's how characters deliver key exposition and reveal their motivations, directly or indirectly. By largely eschewing spoken words, "WALL-E" achieves a feat of storytelling not seen in a century.