15 Best Movies With Narrators You Just Can't Trust

The unreliable narrator is a concept many of us first learned in high school English class, probably while discussing "The Great Gatsby." The term was coined by literary critic Wayne C. Booth in 1961 in his book "The Rhetoric of Fiction," but writers were using this tactic long before we had words to describe a narrator you just can't trust. We've seen it in countless books, but it's also liberally used in films.

We're accustomed to taking the word of a story's narrator, believing them to be our guide in an unfamiliar world. But when the narrator is unreliable, we inevitably learn that they have been misleading us (and possibly themselves) all along. Sometimes this misdirection is intentional — our narrator has been lying to us, spinning a yarn, painting themselves in a better light. In other instances, our narrator is mentally ill, impaired, or simply so biased that we cannot believe their perspective. Sometimes there are hints that our narrator can't be trusted from the beginning of the film; sometimes their unreliability comes as a total shock.

Unreliable narrators typically fall into five subtypes (Pícaro, Madman, Clown, Naïf, and Liar), but no matter which one is employed, it almost always makes for an interesting film! Here are 15 movies with narrators you just can't trust.

Warning: Spoilers ahead!

American Psycho (2000)

Mary Harron's darkly funny cult classic is an exploration of the mind of Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale), an investment banker working on Wall Street in the 1980s who becomes a serial killer. "American Psycho" is a triumph of unreliable narration in part because of the excellent source material (the novel written by Bret Easton Ellis, exploring the correlation between financial success and a lack of empathy) but also because of Bale's superb performance.

It's clear the narrator knows he's not normal — in the opening sequence he says, "There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman. Some kind of abstraction. But there is no real me. Only an entity. Something illusory. And though I can hide my cold gaze, and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours, and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable, I simply am not there." With this startling admission, Bateman gains our confidence. After all, if he can admit to being devoid of basic humanity, why would he lie about anything else?

While Bateman is never diagnosed in the story, many have speculated that he suffers from antisocial personality disorder and possibly additional illnesses, making him the Madman archetype of unreliable narrator. It's only toward the end of the film, after watching Bateman kill numerous people, that we understand the extent to which he's completely lost touch with reality and realize that we've been drawn down a dark and twisting path into his delusions.

Big Fish (2003)

Director Tim Burton's "Big Fish," adapted from the novel by Daniel Wallace, is a whimsical look back at the life of Ed Bloom as he shares stories with his son, Will (Billy Crudup), upon his death-bed. Will, who feels he doesn't know his father well, becomes increasingly frustrated by Ed's fantastic imagination, upset that, with so little time left together, Ed is wasting precious time telling tall tales.

Because of the fanciful nature of the movie, it's easy to get caught up in the stories of Ed's extraordinary life, believing every word he tells us to be absolute truth even though he's spinning a yarn. Ed is a bit of a Clown and a bit of a Pícaro — he enjoys playing with our expectations and is naturally prone to exaggeration, as many natural storytellers are. Unlike many films with an unreliable narrator, however, the surprise at the end of "Big Fish" isn't that Ed is lying. Instead, Will learns that his father's outrageous and folkloric stories were built around kernels of truth when various characters from Ed's tales attend his funeral. The overwhelmingly charming thing about "Big Fish" is that its unreliable narration is used to delight rather than deceive the audience.

Forrest Gump (1994)

Robert Zemeckis' Oscar-winning film "Forrest Gump" is an exploration of unreliable narration through the simplistic perspective of the titular Forrest Gump (Tom Hanks), who some have speculated is autistic. Gump lived an extraordinary life, serendipitously connected to some of the most culturally significant events of the 20th century. Similar to "Big Fish," some of the stories Gump tells while waiting for a bus are hard to believe. His football career and his meeting President Kennedy are miraculous, as are his experiences as a war hero and ping-pong champion.

Unlike "Big Fish's" Ed, however, Forrest isn't being boastful or playful. The action of the film substantiates enough of his more outrageous claims that we ultimately believe Gump's life story. However, his innocence and limited point of view often affect his perception of the world, so that while he's not attempting to deceive the audience, his narration still isn't exactly true. For example, when Gump characterizes Jenny's daddy as a loving father — "always kissing, and touching her and her sisters" — he is unaware Jenny is being abused by her father, whereas this fact is abundantly clear to the audience.

Forrest is an excellent example of a Naïf narrator, someone incapable of fully understanding everything around him. In a way, all stories told through first person narration are unreliable, as they are based solely on one character's perspective, but Forrest Gump's neurodivergent innocence makes him a doubly potent example.

Fight Club (1999)

The iconic '90s cult classic "Fight Club" is perhaps the platonic ideal of unreliable narration, told through the fractured mind of an unnamed narrator played by Edward Norton. In Fincher's film, we are drawn into the narrator's world through his observations about his increasingly meaningless and mind-numbing existence as a cog in a machine ("Fight Club" is based on the bestselling novel by Chuck Palahniuk, and much of Palahniuk's biting commentary about commercialism and corporate culture finds its way into the script). Indeed, some of us might identify so thoroughly with the narrator's dissatisfaction with the rat race that we miss the early clues that we can't trust him. For example, the narrator tells his doctor that he keeps waking up in unfamiliar places, not knowing how he got there, and we see hints of his lack of credibility visually as well, when images of Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) flash on the screen, almost too fast for the eye to register, before he enters the story.

It isn't until the end of the film that we realize, alongside the narrator himself, that Tyler is an alternate personality he created so he could act out his repressed desires. The character played by both Norton and Pitt is a Madman archetype who could be suffering from an undiagnosed mental illness, but whatever the reason for his split personas, "Fight Club's" famed twist ending would never have worked if the narrator wasn't unreliable.

Gone Girl (2014)

Also directed by David Fincher, "Gone Girl" is a masterclass in unreliable narration, gaining much of its brilliance from the novel and screenplay written by Gillian Flynn. When Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike) mysteriously goes missing on her fifth wedding anniversary, her husband Nick (Ben Affleck) is caught at the center of a media frenzy after it's revealed he's been having an affair. When the police find Amy's diary and the clues mount, Nick becomes the prime suspect. The diary paints a picture of a marriage filled with secrets, abuse, and betrayal that left Amy fearing for her life. But in a game-changing twist, it's revealed that Amy isn't missing — she left, intentionally leaving behind a fake diary to frame her errant husband for her murder.

Amy's plan is executed so masterfully we can't help but admire her cunning, an effect enhanced by the way "Gone Girl" handles narration. The film mostly restricts its voiceover narration to Amy and her diary, both of which prove to be unreliable. Nick's perspective is seen through the action of the film, though he does have one piece of narrative voiceover that serves as a bookend to the story. The first time we hear it, at the beginning, it's an ominous manipulation, casting Nick in a suspicious light. But when we hear the same voiceover at the end of the film after Amy's deception has been revealed, we view it from a different perspective. "Gone Girl" is an ingenious example of unreliable narration.

I, Tonya (2017)

"I, Tonya" explores the concept of truth, asking if there can ever be a definitive truth when there are multiple sides to every story. It's based on the contested story of Tonya Harding's fall from Olympic hopeful to disgraced athlete after her rival, Nancy Kerrigan, was attacked shortly before the competition that would determine who got a spot on the 1994 Olympic team. After the attack, Harding came under investigation and public scrutiny, eventually charged for her involvement in the plot and banned from figure skating for life.

The film follows Harding's (Margot Robbie) childhood, her rise to prominence in the skating community, and her public downfall. It's constructed around reenacted interviews with key people, lending "I, Tonya" multiple narrators, all of whom are unreliable to differing degrees and for various reasons, whether they are prone to exaggeration like Harding's former boyfriend Shawn (Paul Walter Hauser), who went to jail for his role in the attack, or, Jeff (Sebastian Stan) Harding's ex-husband, who lied out of self-preservation but admitted to being responsible for ruining Harding's career.

The film addresses these divergent stories directly, with Harding herself ultimately stating, "The haters always say, 'Tonya, tell the truth.' There's no such thing as truth ... Everyone has their own truth." This film is the perfect argument that any first-person narrator is ultimately unreliable, regardless of their motivations.

Joker (2019)

Joaquin Phoenix explores mental illness through the character Arthur Fleck in this dark iteration of a classic villain's origin story in "Joker." This film is a slight departure from our theme — Arthur isn't a traditional narrator, and there are no voiceovers, but we experience the film from Arthur's twisted perspective, and it's unclear how much of what we're seeing is real.

Although the ending of the film is ambiguous (is the whole movie just a delusion Arthur is experiencing as a patient at Arkham Asylum?) Arthur's imagined relationship with his neighbor Sophie (Zazie Beetz) is evidence that he can create a complex delusional world. In the climactic scene, Arthur sings along with the Frank Sinatra song "Send in the Clowns" — when Arthur's singing syncs with the music, we understand that the soundtrack and original score are reflections of Arthur's mental and emotional state. Arthur actually hears the music, as we see during his dance routine on the stairs.

Director Todd Phillips acknowledges this interpretation, telling IndieWire, "There's many ways to look at the movie. He might not be Joker. This is just a version of a Joker origin. It's just the version this guy is telling in this room at a mental institution. I don't know that he's the most reliable narrator in the world." Arthur Fleck might look like a clown, but he is a Madman archetype, incapable of discerning between reality and his own delusions, making "Joker" one of the more potent representations of the unreliable narrator.

Life of Pi (2012)

Director Ang Lee explores the power of storytelling through the visually stunning adaptation "Life of Pi." The film's narration is framed as a writer interviewing a man named Pi Patel about his miraculous survival story, stranded in the Pacific Ocean as a teenager. Pi tells the writer about growing up in India, where his family owned a zoo, and how they set out on a freighter to sell the animals in North America. After the ship sank, according to Pi's story, he survived on a lifeboat with a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker for 227 days before finally washing ashore in Mexico.

Pi's tale is fanciful and hard to believe, leaving the writer wondering how much of it really happened. And indeed, when Pi tells the writer a different, far darker version of the story (the one he told insurance investigators), we realize Pi likely adopted his inventive version of events to preserve his own sanity.

From the outset, we know Pi is an unreliable narrator, a Pícaro given to flights of fancy and exaggeration. What makes "Life of Pi" an exceptional study in unreliable narration is that it explores the importance of storytelling to the human spirit. Pi isn't trying to deceive us or make himself out to be more important than he is — he's just telling us a good story, which also happens to be the story that helped him survive. Humans don't always want the truth. Sometimes, we prefer a lie.

Memento (2000)

"Memento" is a nonlinear, mind-bending maze, a story about a man with a traumatic brain injury causing short-term memory loss and an all-consuming hunger for vengeance. The story is told through the fractured mind of Leonard, a former insurance fraud investigator searching for the man who raped and murdered his wife, and cuts back and forth between color sequences that move backward in time and black-and-white sequences that move forward in time, eventually meeting in the middle, when the truth of what's really going in is revealed.

Leonard's condition means he can't rely on anything or anyone outside himself, trusting nothing but his own handwriting and his system for recording information about his investigation with notes and tattoos. And since he's our point-of-view character, we also believe he's the only person in the film we can trust. Initially one might think of Leonard as a Madman or Naïf archetype, his shattered mind skewing or limiting his perceptions. But in the last section of the film, we realize he's a Liar — not only to us but to himself. Leonard's wife is alive, but in a coma thanks to Leonard's own unwitting actions, and he's searching for a man he's already found and killed, helped along by a system he himself set up in order to escape the truth. The true horror of "Memento" is that Leonard has trapped himself in an endless cycle of loss and revenge, a story made possible by the film's brilliant use of unreliable narration.

The Great Gatsby (2013)

The American novel "The Great Gatsby" is the classic example of an unreliable narrator, one who doesn't necessarily intentionally deceive, but does so out of denial and devotion. Director Baz Luhrmann's Oscar-winning interpretation is visually dazzling and just as layered as the book. Despite Nick Carraway (Tobey Maguire) being a likable character, one shouldn't assume his version of events is true. Nick's narration is suspect for various reasons, all of which are revealed within the action of the film.

First, Nick isn't omniscient. He's only aware of the things he's present for and what he has been told by others (and unfortunately, people lie). Second, Nick plays down his own foibles, minimizing his past relationships with various women, casting himself in a more noble light, holding himself up as a person who does not judge others when he, in fact, judges everyone. If Nick warps the truth to make himself look better, could he not do the same for Gatsby (Leonardo DiCaprio), whom Nick clearly idolizes?

Then there's the question of Nick's drinking. Nick writes this story from a sanitarium while being treated for alcoholism years after meeting Gatsby. While Nick claims to not have been a heavy drinker before moving next door to Gatsby, he throws himself into the boozy decadence of the Roaring Twenties after arriving in West Egg. We can never be certain Nick's perspective has not been warped by his fondness for liquor, his regard for Gatsby, or his dislike of other characters.

The Sixth Sense (1999)

M. Night Shyamalan's breakout film, "The Sixth Sense," is the story of Cole Sear (Haley Joel Osment), a boy haunted by the ghosts of the dead, and Malcolm Crowe (Bruce Willis), a therapist who recently survived being shot by a former patient. Malcolm helps Cole use his ability to see and communicate with the dead to help the ghosts find peace, but the final reveal — that Malcolm didn't survive the shooting at all — is one of the most jaw-dropping moments in cinematic history, kickstarting Shymalan's reputation for twist endings.

This ghost story is fascinating because it explores how powerful denial is — how it can warp our perspective, making us incapable of seeing the truth before our very eyes. What is truly fantastic about this film, however, is that knowing the truth doesn't ruin subsequent viewings. Watching the movie again, you realize that none of the characters other than Cole ever directly interact with Malcolm (including his own wife, played by Olivia Williams), making it impossible to not ask ourselves why we didn't put together the clues earlier. "The Sixth Sense" is a perfect example of how easily we believe the stories we are told by an unreliable narrator, despite abundant clues that something isn't quite right.

The Usual Suspects (1995)

After mob warfare breaks out on a boat in the Los Angeles harbor, the sole survivor tells a story that began with five criminals, Keaton (Gabriel Byrne), McManus (Stephen Baldwin), Fenster (Benicio Del Toro), Hockney (Kevin Pollak) and Roger "Verbal" Kint (Kevin Spacey), who meet in police custody and plan a heist that ends in death for all but one. Verbal is the quintessential unreliable narrator, spinning a tale so detailed and believable he deceives Agent Kujan (Chazz Palminteri) and the audience in the crime thriller "The Usual Suspects."

The plot of this film is a twisting labyrinth, and Spacey's incomparable performance makes it shine. Verbal tells an incredible story, ultimately suggesting that Keaton was behind everything and was, in fact, the mythic criminal mastermind Keyser Söze. It's only after Verbal leaves the police station, vanishing into the crowd, that Kujan puts the pieces together and realizes that Verbal fabricated the entire story, including his own identity.

When Verbal, a consummate unreliable narrator, is done spinning his web of lies, we are left to ponder whether there was any truth at all to his tale. Who is Keyser Söze? Is it Verbal himself, as the police sketch in the final scene suggests? Or is Söze a convenient boogyman, a distraction created to throw us off? The last line of the film is deliciously ambiguous: "The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn't exist. And like that — he's gone."

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Martin Scorsese's biopic "The Wolf of Wall Street" is an interesting example of unreliable narration because it's ostensibly based on a true story, and because it's narrator is Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio), the notorious stockbroker who lived it. But even the movie version of Belfort is a Picaro prone to exaggeration and bragging, and he was admittedly on heavy drugs during the period of his life the film covers, meaning his word and perspective lacks credibility with the audience — Scorsese plays with Belfort's narration, acknowledging its unreliability, very early in the film.

Watching Belfort at work selling penny stocks and thumping his chest, it's obvious he's a hustler who will say anything to make a deal. Why should we believe anything he says? Sometimes Belfort is caught in his lies, but he's rarely phased by this, which is unsurprising considering the many laws he broke while building his empire. We also see Belfort's dishonesty in his relationships — he deceived and abandoned his first wife to marry Naomi Lapaglia (Margot Robbie), who he then cheated on repeatedly.

"The Wolf of Wall Street" is undoubtedly entertaining, but it's easy to doubt the veracity of some of the more outlandish events, especially since Danny Porush, the real-life counterpart to Jonah Hill's Donnie Azoff, disputes some of what is represented in the memoir and the film. That said, despite the unreliability of Belfort as a narrator, the wildest thing about this movie is that most of it actually happened.

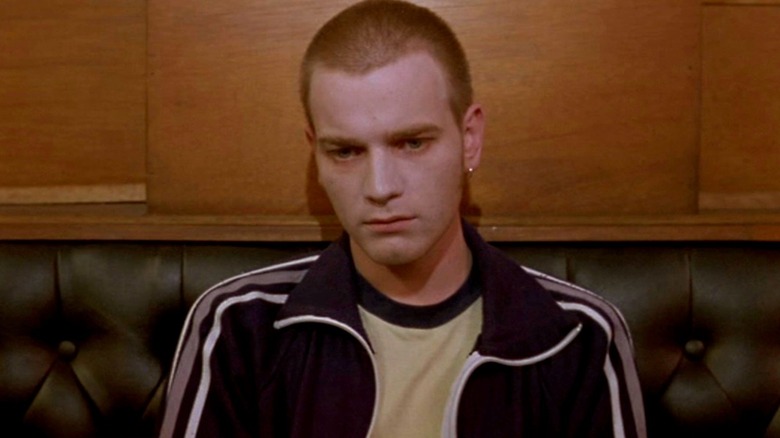

Trainspotting (1996)

The iconic 1996 film "Trainspotting" explores the lives of a group of drug addicts in Edinburgh, Scotland, through the perspective of Mark Renton (Ewan McGregor), a narrator we can't trust because he's on drugs or trying to get clean throughout the movie. Not only does Mark narrate "Trainspotting," we see the world of the film through his skewed perspective, experiencing his hallucinations and delusions while he detoxes from heroin. The scene in which Mark climbs into the worst toilet in Scotland is a disgusting example of his active imagination.

Although Mark shares many meaningful insights about addiction, his cycle of drug use and detox negates his credibility with the audience. Mark's deep-seated denial also skews his perceptions — he repeatedly claims, over and over again, that this will be his last dose of heroin, making it impossible for us to believe him by the end of the film. We don't know if he will stay clean, even after stealing a bag of cash from his friends to start a new life.

Mark might tell us he is "choosing life," but we can't know if he will use that money to set up a more sustainable existence for himself, or if he will shoot it into his arm, continuing in his destructive cycle of addiction. Despite finding ourselves rooting for and liking Mark, his less-than-savory choices, combined with the fact that he lies to himself as much as he lies to us, makes it impossible to trust his narration.

Who Am I (2014)

This German-language film streaming on Netflix is an excellent example of an unreliable narrator shaping the story of the film through intentional deception. "Who Am I" has big "Fight Club" and "The Usual Suspects" vibes, so prepare yourself for a plot twist or two in this techno-thriller about a group of subversive hackers known as Clowns Laughing At You (CLAY).

After being arrested for breaking into a server room and stealing the answers to a test, Benjamin (Tom Schilling) must do community service hours as part of his probation. During community service, he meets Max (Elyas M'Barek), who introduces Benjamin to his friends Stephan (Wotan Wilke Möhring) and Paul (Antoine Monot Jr.). The four men form CLAY and are soon pursued by Europol because of their ostentatious hacks. When things get out of control, Benjamin turns himself into Agent Hanne Lindberg (Trine Dyrholm), hoping to cut a deal.

Benjamin's elaborate story is initially presented as truth, but both the audience and Lindberg come to believe Benjamin has multiple personality disorder and committed all the crimes himself. The brilliance of this film, however, is that Benjamin is a doubly unreliable narrator — he tricks us into believing him a Madman, when in fact he is a Liar who concocted a story deliberately designed to lead Lindberg to the multiple personality diagnosis, part of a scheme to erase the identities of himself and his friends. Thanks to its unreliable narrator, "Who Am I" masterfully executes an absolutely exquisite misdirect.