Disturbing It Moments From The Book Cut From The Movie

The 2017 big-screen adaptation of Stephen King's It is a major success with critics and audiences—due in no small part to the way the Andrés Muschietti-directed movie focuses on the first half of the book, incorporating its most essential elements while sidestepping some of its more controversial or uncomfortable moments.

Some of the stuff the movie left out may still make it into It: Chapter Two as some sort of flashback. But for now, these are the most disturbing scenes from It—the first half of the book in particular—that were left behind during the long journey to theaters.

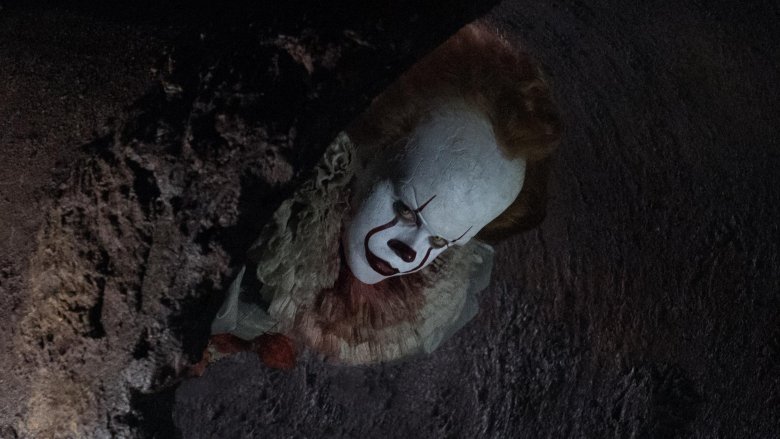

The sewer escape

In the movie, the Losers have no trouble exiting the sewer system after their battle with It. In the book, however, they find themselves trapped, unable to remember their way out of the underground tunnels they entered to tangle with Pennywise. The solution? At her suggestion, all six of the boys have sex with Beverly Marsh in quick succession so they can be united again and find their way back to the Barrens.

There's been a lot of debate about whether this is belittling, abusive, or even empowering for Beverly, but even Stephen King himself has since walked back on its value to the story. "I wasn't really thinking of the sexual aspect of it. The book dealt with childhood and adulthood," he later explained. "Intuitively, the Losers knew they had to be together again. The sexual act connected childhood and adulthood. It's another version of the glass tunnel that connects the children's library and the adult library. Times have changed since I wrote that scene and there is now more sensitivity to those issues."

Like the 1990 TV miniseries, It ignores that part of the plot, which saved the filmmakers (and child actors) from having to try and bring such a problematic scene to life.

Patrick Hockstetter's cruelest act

In the movie, Patrick Hockstetter is hardly a central figure to the story. He's but one of several lackeys belonging to Henry's group of bullies, and the most significant thing about him is the fact that he pulls an Arachnophobia move by fashioning an aerosol flamethrower to torment the Losers. He's clearly a jerk, but he's not nearly as terrible as he was in the novel.

Patrick is an exceptionally disturbed young man in the book, and through his backstory, we learn that before he even started grade school, he'd already committed murder by suffocating his baby brother in his crib. See, Patrick was/is under the delusion that he was the only "real" person—and if his brother had the chance to grow up, he might become one too, and Patrick simply couldn't let that happen. It's not clear why this part of the story was streamlined for the movie, except perhaps to save time and narrow the narrative focus. But it could also very well be that the filmmakers had no interest in showing the suffocation of an infant, which is ... understandable.

Patrick's death scene

In the It movie, Patrick's death scene is entirely different than the way it went down in the novel. He tracks the Losers down to the Barrens' sewer drain on Henry's behalf, with the full intention of attacking them and probably delivering them to Henry for even more punishment. But they manage to evade him long enough for Pennywise to show up—and we later see Patrick being dragged helplessly around the Well House, his doomed condition almost pitiable.

On paper, however, Patrick being claimed by It has very little to do with the Losers. He, Henry Bowers, and the rest of their group go to a spot in the woods where they store the dead bodies of animals they've tortured in a refrigerator. At first, they just go there to light their farts on fire, but after he and Henry find themselves alone, Patrick makes a sexual advance on Henry, who accepts to a point—until his homophobia kicks in, and he starts slinging slurs at his friend before taking off. Left alone, Patrick is attacked by It in the form of swarming bugs, a death that matches his worst nightmare. (All of this happens before Beverly Marsh's innocent eyes, making the shock value even more intense on paper.)

Henry Bowers' unhappy home life

In the movie, Henry Bowers' father is portrayed as an alcoholic police officer who has no qualms about accosting his son in front of his friends. When Henry and the rest are caught playing with his gun, for example, Butch Bowers unloads the clip near their feet to show that they aren't mature enough to handle such a weapon. Otherwise, his cruelty is mostly hinted at, like the moment Henry expresses sincere fear that his father will "kill" him if he loses his switchblade.

In the books, however, Henry's dad's rancor is the only constant in his life. Butch is shown as a Marine veteran who has developed psychosis and is verbally and physically abusive to his family, including Henry. The only thing Henry seems to be able to do right by his father is express and act upon their shared racism against the Hanlon family, which culminates in Henry poisoning Mike Hanlon's dog Mr. Chips—just as his father had poisoned the Hanlons' livestock before.

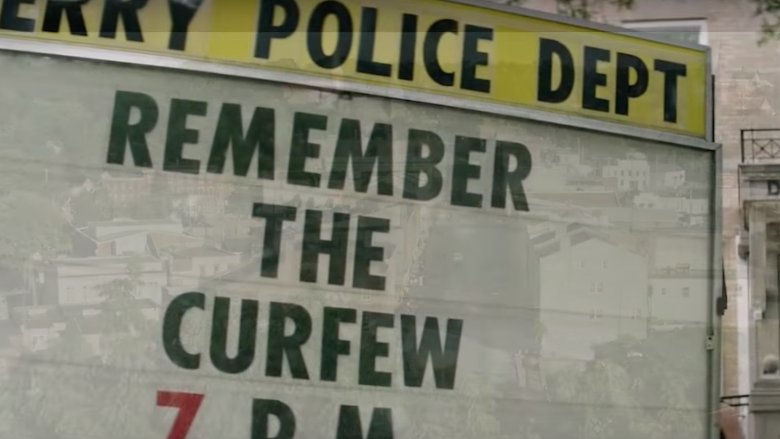

The town blaze

The It movie handles Mike's history in very obscure terms. We're told his parents died in a gruesome house fire and that he'd seen them burn, which is why he's so haunted by the image of burnt hands reaching out from the meat store's alley entrance. He's also clearly tormented by Henry and his friends while being told that he and his family don't belong in the town. He's shown as the bearer of some bad news about the town's history, courtesy of his grandfather, but for the most part, the role of the resident historian of the group is given to Ben Hanscom instead.

The book goes into a lot more detail about Mike's pain. Instead of merely bullying Mike, Henry routinely uses racial slurs against him, just as his father had done to Mike's dad. And the notorious town fire referenced in the movie took place at a club called the Black Spot, where Mike's dad was a guest the night it was burned down by the Ku Klux Klan. Mike's dad survived the incident in the story, but he got a glimpse of It in the form of a giant bird, which is the same version of the terror that Mike sees in the novel before joining the Losers. It's Mike's dad who encourages him to study the town's sinister history, which is how he becomes the librarian—and the only one to stay in Derry after the rest of the Losers' Club leaves.

The death of Eddie Corcoran

Poor Eddie Corcoran. Not only is the poor kid's story one of the more tragic subplots in the book, but he didn't even make it into the movie. A student at the same school as the Losers, Eddie's stepfather severely abuses him and his brother Dorsey—and actually ends up killing his little brother with a hammer, which leaves Eddie on the run for his life. He ends up in the Barrens where he encounters It, which takes the form of his recently deceased little brother before turning into a gill man and decapitating Eddie.

Perhaps his death was cut for time, or the special effects of the swamp monster might have been too expensive to put together for a secondary character, or perhaps the filmmakers wanted to rein in the amount of parental abuse in the movie. After all, Beverly's father's aggression was disturbing enough on its own.

Eddie Kaspbrak's first encounter

Eddie Kaspbrak's first encounter with It in the movie is relatively similar to the novel: he passes by the creepy house on Neibolt Street and runs into a leper, which is the culmination of his worst fear of severe and contagious illnesses. The leper picks up one of his many prescription pills, which are actually just placebos because his mother is a helicopter and a vicarious hypochondriac, and asks him if they'll help him with his own condition before giving chase.

In the book, however, the scene's a little more adult. Many readers perceived Eddie's mother as not just domineering over his physical development by way of her over-treatment, but also stunting his emotional and sexual maturity by consistently demanding that affection of any kind be reserved for her. The leper doesn't make fun of his medication; instead, he offers to perform sexual favors in exchange for cash, as a nod to the fact that Eddie's been taught to fear his sexuality, most likely because of communicable diseases, and the Neibolt house was regarded a former prostitution den. That's ... a little too heavy to explore in a single scene, so it's easy to understand why it was ditched.

The goon squad

In It, Henry Bowers is shown tumbling down the well after Mike Hanlon fights him off—and aside from Patrick, the rest of his bully crew seems to get out of the movie without getting hurt.

In the book, though, they're all are caught by It in the sewers after chasing the Losers. Vic gets his head torn off by the monster, who appears as Frankenstein, and Belch has his face ripped in half after trying to defend Henry from It. Afterwards, Henry runs away as It chases Stan, who's watched all of this happen, allowing Belch to die as he escapes from the sewers. Henry still gets his comeuppance, though, as he soon finds himself in handcuffs and framed for all the recent murders of the town's children.

The Ritual of Chud

The ending of the It movie certainly simplified things when it came to the Losers' first banishment of the beast. Once they rescue Beverly from her floating, glaze-eyed comatose state, they're fearless against the creature; after they manage to injure It by striking its head, It slinks into the well and the killings stop ... for now.

In the book, however, there's a lot more to it. Bill Denbrough uses an ancient technique called the Ritual of Chud, which takes him into a multiverse where he encounters the universe's creator, a giant turtle named Maturin. The turtle informs him that he can only defeat It in a battle of wills, so Bill makes It bring him back through the power of his mind, weakening It enough that the Losers can make a physical attack. It's a much more supernatural/celestial process than what we see onscreen, and if It is any indication, both movies may bypass this bonkers aspect of the story altogether.

The Native American ritual

The movie also completely omitted one book scene that would probably be regarded as insensitive—and perhaps a bit of cultural appropriation. In the scene, Bill leads up a Native American smoke hole ritual in an effort to find out more about the demon that's doing so much damage to Derry. Bill and Richie end up staying in the hotbox long enough to realize that It is an evil force that's sucking the lifeblood out of the town. It's an important enough realization, but one that's easily substituted with a rudimentary history lesson. It's another instance of the movie avoiding unnecessary controversy—which is pretty interesting, since it's still a movie about kids battling a child-murdering monster.

Ben's first encounter

Early in the book, Ben Hanscom is shown volunteering to stay late to help his teacher finish some last-minute tasks, and by the time they're done, the streets have cleared. It's brutally cold, and although Ben's teacher offers to give him a ride home later once her husband arrives, he decides to go it alone.

Along the way, he spots a clown standing on the ice, clutching balloons and offering Ben one, with his usual offer for the kid to float. What's frightening about it is that Ben does want that balloon and feels sucked into Pennywise's mental grip, which is only broken by the town's clock chiming to indicate the top of the hour. Talk about being saved by the bell.

The werewolf

The It movie did a great job of sneaking in a lot of the pop culture-inspired monsters that loomed large over the Losers, but the werewolf that came into play at the Neibolt Street house only appeared in a blink-and-you'd-miss-it moment. It was more of an Easter egg, but there's more to that scene in the book.

As in the movie, the werewolf arrives during Bill and Richie's journey into the house, but while Richie's perspective shows It as the four-legged freak show, Bill sees something different. As they escape on Bill's bike Silver, he describes It as a clown in a varsity coat, which runs counter to Richie's memory of the monster. It's a subtle difference, but the scene proves that It looks different to different people depending on their particular fear, which makes it that much scarier than some bozo with big teeth. The absence of the wolf also means that the book's weapon—silver slugs—aren't a factor in the movie, which is why the Losers end up fighting with a bolt gun instead of their trusty slingshot.

The standpipe

Although Stan's first encounter with It in the movie took place in his father's office, the literary version was a lot creepier. As a child, Stan is an avid bird watcher and heads down to the Barrens to do some spotting near the Standpipe—a notoriously off-limits part of town, since it claimed too many lives (including a baby) when it was open to the public.

After seeing the Standpipe appear to float, Stanley curiously goes inside. The door shuts, locking him in, and he hears a voice claiming to be "the dead ones." He only manages to escape by chanting the names of birds from his guidebook, but the only wild thing he sees that day is a dead body beckoning him back into the watery hellhole. Despite what he's seen, Stan still has trouble wrapping his head around what's happened and needs more proof of It's existence. This all goes to show, of course, that Stan has more trouble accepting It than the rest, which will have deadly consequences for him later in life.

Georgie's picture

In the It movie, the kids' projector slideshow develops a mind of Its own and slowly churns out a more-than-photorealistic image of Pennywise. That might be a clever way of getting the feel of the scene across while embracing the movie's adjusted timeline, but there's still something particularly sinister about the way this moment went down in the book.

As reimagined by the miniseries as well, Bill is looking at a photo album with some innocent family pictures of Georgie. But one photo of his lost little brother starts to move, winking at him and promising that he'll see him soon, just before the book starts gushing blood. Making matters worse is that the image represents Bill's freshest memory of Georgie, since it was taken just days before his death. When he shows Richie and it moves again, Bill tries to actually reach into the photo and gets lashed on the hand. Sure, the It movie brought Georgie back to terrorize Bill, but the scene as written was a spine-tingler for anyone who read it.

The disappearance of Chad Lowe

Other than Betty Ripsom and Patrick Hockstetter, the children who've gone missing in the It movie are largely ignored. In addition to removing the death of poor Eddie Corcoran from the movie, the pic also passes over one of the most disturbing disappearances of all: Chad Lowe. Grown-up Mike Hanlon makes mention of the boy later when recapping the town's attitude towards the missing kids, pointing out Chad's case to the cop who wants to wave away the deaths or disappearances as coincidence.

Lowe, Mike reveals, was just three and a half when he went missing the same year the Losers made their first stand against It. Granted, Pennywise has never seemed to have any sensitivity for the ages of his victims; after all, Georgie was just six when his arm was snatched off on the street. But little Chad was still just a toddler, which makes his probable death even more gruesome. It's a footnote to the whole story of It, but an especially unsettling one.