Things Only Adults Notice In James And The Giant Peach

Everything was a lot bigger when we were children, since we were literally a lot smaller. Adults were towering, impossibly large people that had access to heights and worlds we couldn't even imagine, and twin mattresses were vast expanses after the comfort of a crib. To grow up is to see the world shrink in slow motion, which our memory makes into a hazy blur— perhaps this is why so many children's stories are about disparities in size. Whether it's Alice's psychedelic journey of shrinking and growing in Wonderland or children who discover miniature people in "The Borrowers," lots of well-known kids' stories tap into the sense of shifting perspective that accompanies our childhoods in our minds.

Roald Dahl had an eternal obsession with just such disparities. His work is full of odd sizes, including "The Big Friendly Giant," "The Enormous Crocodile," and of course, "James and the Giant Peach," the 1961 eternal classic that was adapted into an animated film by Henry Selick in 1996. The movie rather faithfully adapts Dahl's work into a strange, whimsical journey that feels true to something about childhood, seamlessly weaving live action and claymation together to tell a story that operates on the fluid, dreamlike logic of a child's imagination. And while the plot isn't exactly designed to stand up to analysis from grown-ups, there are a few discrepancies that simply can't be ignored when looked upon with older eyes. These are the things about "James and the Giant Peach" only adults notice.

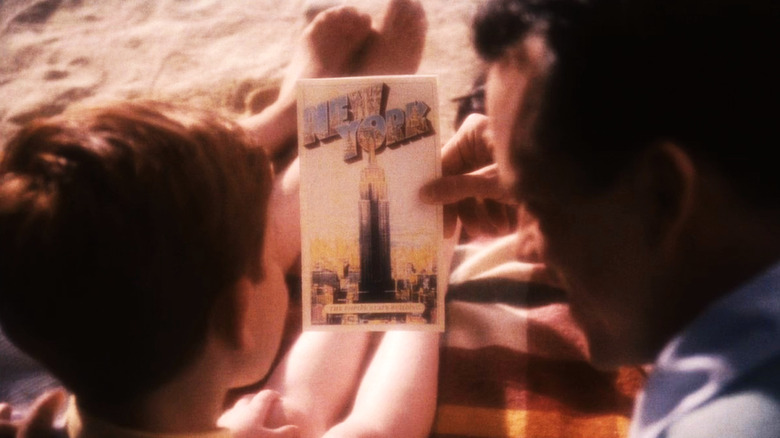

Why does James want to move to New York City?

James, like many Roald Dahl protagonists, is a tragic orphan, his parents having been killed by a rampaging rhinoceros in an accident that's never fully explained. Since he's worked to the bone and verbally abused in the care of his evil aunts Sponge and Spiker, it makes sense that he'd long to escape to the bright lights of New York City, across the Atlantic Ocean. But you have to wonder why his dearly departed parents wanted to move there in the first place. In the very beginning, as we see gauzy flashbacks of James' happy time with his parents, we see them on a beautiful beach talking about moving to New York. But the beach honestly looks at lot nicer.

Sure, as James' dad says, there are hundreds of other kids there to be friends with, but a whole lot of parents would likely rather raise their kids in a quiet, cozy town on the English coast than a densely-populated city. It's nice that James has the dream of New York to sustain his hopes later, but it's never fully explained why his parents wanted to uproot their life and immigrate to America at all, beyond the vague razzle-dazzle that the Big Apple allegedly offers.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

No way should James trust the crocodile tongue guy

Again, it's not hard to understand why James would accept help from literally anyone who offered it given his desperate circumstances. But watching "James and the Giant Peach" with mature eyes, the anonymous man who shows up to offer a bag of weird glowing worms in a paper bag sets off all sorts of red flags. Who is this guy? How does he know James' name already? He's raggedly dressed, oddly insistent in his approach, and offers James a bag of ... crocodile tongues? But don't worry, they've been "boiled in the skull of a dead witch."

While James certainly takes action and shows initiative the rest of the way, it's just strange that the inciting incident of the entire story is just handed to him in a bag by a strange dude, with nothing more than the vague promise that "marvelous things will happen." Forget the Berenstain Bears and every after-school special you've ever seen, kids, just go ahead and trust strangers. Especially if they have fingerless gloves and make too much eye contact.

Is James actually turned into clay?

Beyond the growing of the peach and the ability of all James' new bug friends to talk, one of the "marvelous things" that the crocodile tongues cause to happen is the transformation of James himself into clay. Or something — it's not clear what the film's transition into claymation actually means to the characters, but Mrs. Ladybug makes a point of taking a mirror out of her handbag to show James his new, much bigger head and significantly beadier eyes. He's surprised for a brief second, and then immediately moves on to having adventures with his new friends.

The movie takes the time to show James' silhouette changing as he crawls inside the peach, implying a physical transformation of some sort, but whether he's actually clay or something else is never explained. When he and the peach fall from the clouds near the end of the film, James changes back, but the bugs eventually exist outside of the peach as their claymation selves, so it's just kind of confusing how the magic works and what the mechanics of the reality of the film really are. In terms of cinematic execution, the interweaving of live-action and claymation is brilliant, but it's strange that "James and the Giant Peach" calls attention to the transition between the two without offering any answers to the questions this raises.

Does the mechanical shark represent something?

The mechanical shark that functions as the first huge obstacle for the peach adventurers is a little hard to understand. Is it bionic, or entirely mechanical? Does it think for itself, or does it have a human crew that sinks along with it? The first thing we see it do is devour a school of tuna and then spit out fish heads on plates that look a lot like the rotten meals that James was given at his aunts' house — does the mechanical shark represent their hold over James?

As awesome and steampunk as it is, the mechanical shark muddles the story a little bit when you apply any sort of interpretation to it. It's either a real, terrifying thing that seems anachronistically advanced compared to the rest of the technology we see, or it's a symbolic representation of Spiker and Sponge's insidious sway that makes you wonder if the entire story is a dream of some kind.

The bugs would have eaten one another

Granted, depending on what kind of kid you were, you might have been more familiar with the dietary habits of centipedes, grasshoppers, glowworms, and earthworms than you are as an adult. But watching "James and the Giant Peach" and thinking about it as an adult, when the bugs start to get crazed with hunger during the journey, you can't ignore an obvious thought: Miss Spider would probably eat the rest of them.

Casual Googling reveals, horrifyingly, that Mr. Centipede would also likely have chowed down on his fellow bugs, and in a pinch Mrs. Ladybug is surprisingly predatory, as well. As none of them are fruit flies, one somehow doubts that James' solution — start eating the peach itself — would have actually prevented any bloodshed if the bugs were true to their real-life counterparts' dietary preferences. Maybe they should have all been fruit flies, just for verisimilitude.

No dark concept is off limits

Pushing the boundaries of the tragic and macabre in children's entertainment is what Roald Dahl is known for, not to mention director Henry Selick and producer Tim Burton. But the "James and the Giant Peach" adaptation piles the darkness on and never lets up. James' parents bite it within the first few minutes, and we witness first-hand his exploitation and constant beratement from his aunts. Even when he escapes on the peach, James is haunted by Spiker and Sponge in a trippy nightmare that looks like something Terry Gilliam or Edward Gorey sees on bad acid.

One of the grimmest concepts of all is brought up for the sake of a pun. When our heroes are lost in the frozen North Atlantic, Mr. Centipede, who has fallen asleep while steering, decides to jump in the water to find a compass from a shipwreck. But Mr. Grasshopper, making an incorrect assumption, cries out, "Good heavens! He's committed pesticide!" Even suicide isn't off limits in this film, but like all Dahl-inspired tales, an absurdly happy ending balances the entire thing into a singular, confusing equilibrium.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

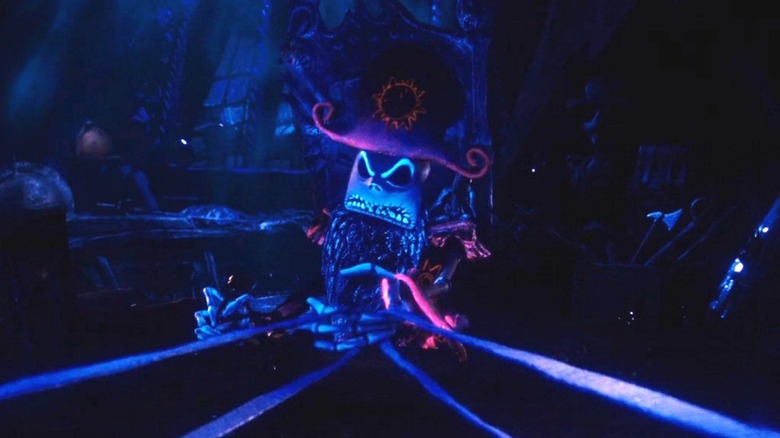

The unsubtle Nightmare Before Christmas reference

No one begrudges Henry Selick a victory lap celebrating "The Nightmare Before Christmas." His feature film directing debut was one of the most successful stop motion movies ever, and even just three years after its release, it was becoming a classic Halloween (and Christmas) movie. It's a fun (though somewhat obvious) wink at his own work when the remains of a pirate on a sunken ship in "James and the Giant Peach" looks almost exactly like Jack Skellington, the protagonist of Selick's first film.

It's a bit much to have Mr. Centipede drive it all the way home by mumbling "Skellington?" to himself as he approaches it, however. Did they know each other? Are the films set in the same universe? Does the Centipede just coincidentally refer to skeletons as "skellingtons"? This might be nitpicking, but hey, that's what adults do that children don't. The visual reference is fine — naming the character is overkill.

The rhinoceros is a pretty vague metaphor

The rhinoceros haunts James throughout the course of "James and the Giant Peach," but it's never real enough to feel all that threatening, and it's a little too all-purpose of a stand-in for bad stuff to really serve the story as a metaphor. It killed his parents, so maybe it represents the cruel and random hand of fate? But then, his aunts use its looming presence as a reminder not to go out into the world on his own, so it's also fear?

When James and the gang at last approache New York, storm clouds suddenly materialize above the city, and the rhino appears, formed out of the rain and mist, threatening the entire crew of the peach. So is it real? James helpfully shouts "You're not even a real rhino! You're just a lot of smoke and noise!" in a moment of climactic catharsis, but then it seemingly retaliates by striking the peach with lightning. Immediately after this, James stands up to his aunts for the first and final time, so perhaps the rhino represents their malevolent authority, as well, but the metaphor is never focused enough to truly know what to make of it. Parent-eating rhinoceroses: just one of those things that come up in a boy's life.

NYPD's least effective policeman

The New York City of "James and the Giant Peach" turns out to be as loosely-defined and dreamlike as the rest of the story, including one of the most bumbling and ineffective policemen yet committed to film. After the fire department safely gets James and the peach down from the Empire State Building, the beat cop that was first on the scene is seemingly in charge of all decision-making on behalf of the city, but clearly has no idea what to do. He's at first deferential to Spiker and Sponge when they arrive with custody papers for James and a picture of the peach, but wavers when James explains how cruel they are.

When the evil aunts attack James with fire axes, it's up to his bug friends from the peach to do anything at all about it. The policeman only orders them arrested after Miss Spider has them bodily encased in webbing, as if he's just snapped to attention after watching grown adults try to murder a child for several minutes. There's no crowd control whatsoever of the hundreds of clamoring onlookers and no attempt to lock down the scene. Truly not the best day for one of New York's finest.

New York City, a place of no laws of any sort

The end of "James and the Giant Peach" is pretty satisfying on a happy ending level, but smooths over nearly all of the pragmatic details of the real, adult world on a logical level. Despite their brazen axe-murdering attempt, it would still probably be a bit of a court battle to get around the guardianship of Spiker and Sponge and emancipate James. And it seems strange that the city would be comfortable with him living in a cottage made of a peach pit in the middle of Central Park, under the custody of giant talking bugs.

But, as we learn from newspaper headlines before the credits roll, this New York City doesn't really have laws of any sort. Or at least, much like the famous loophole in "Air Bud," there must be no law that says a centipede can't run for mayor, or a spider can't own a night club, and so on. As the saying goes, only in New York!

The government would dissect the bugs

It's beautiful and sweet that James and his new bug family get to live together in New York at the end of "James and the Giant Peach." It's impossible not to consider, though, what would really happen if several gigantic, talking insects floated down from the top of the Empire State Building: absolute pandemonium. It's nuts that not a single person reacts with fear, the way James himself did when he met them, and even more nuts that the government doesn't immediately arrive to take the bugs to labs that they'll never return from.

Men in black sunglasses would definitely show up to escort the bugs to some men in white coats, and even if they survived the poking and prodding, they'd most definitely live out their days in captivity, not as influential New York citizens. It would be a bleak ending, indeed, for a children's movie, but when you think about it, would it be that much darker than the rest of the film?