The Real Reason Law & Order: SVU Is Losing Longtime Fans

After a spike in ratings following its reintroduction of Christopher Meloni's Elliot Stabler, "Law & Order: Special Victims Unit" recently hit, as TV Line reports, "an all-time demo low." While many a former fan has cited the series' supposedly newfound liberal agenda as their reason for revolt (as in this Reddit thread, and this one, and this one ...) the reality is that "Special Victims Unit" has always been inspired by current events. More specifically, like "Law & Order" before it, the series has always promoted a politically progressive agenda (see: its consistent stance on reproductive rights, or Richard Belzer's Munch hating on Newt Gingrich all the way back in Season 1). So, what gives?

While there are several elements at work here (including the interpretive gap between watching a current events-inspired show in real time and watching it in syndication), the biggest danger to the long-running series isn't its politics, but its lackluster approach to storytelling.

In a well-intentioned but disastrously-executed attempt to pull the police procedural into the 21st century, "SVU" sacrificed the two most compelling (not to mention titular) aspects of the series. Current episodes contain little if any investigation, and as a result, the complex lead-up to the trial and trial itself have also been lost. These were the series' main means of depicting, exploring, and organically (read: constructively) promoting its view on a given debate. Without them, "Special Victims Unit" has lost the nuanced plot lines that allowed its stance to come off as thought-provoking, as opposed to preachy, along with any semblance of narrative pull. In fact, "Special Victims Unit" hasn't become more preachy than it already was — its approach has simply become less interesting and effective.

SVU's half response to current events left its structure lacking

In fairness, as an already progressively-aligned series, "Special Victims Unit" had its work cut out for it on the cusp of its 22nd season. Articles such as Rolling Stone's "Sorry, Olivia Benson Is Canceled Too," comprehensive studies from organizations such as Color of Change, and the call for an overhaul (or even cancellation) of cop dramas (via BBC), forced the series to acknowledge its idealistic depiction of law enforcement. Had "Special Victims Unit" chosen not to acknowledge these changing cultural norms, it would have come off — at best – as hypocritical, given the liberal bent of its first 21 seasons.

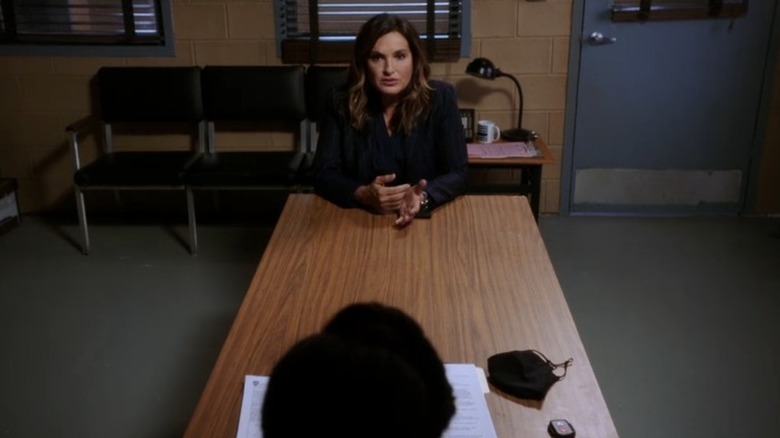

Unfortunately, rather than commit fully to the difficult task of real evolution, the series touched on, then quickly moved on from, the topic of its detectives' racial biases. Mariska Hargitay's Olivia Benson was (contrary to Rolling Stone's prediction) called-out for her bias-driven blind spots in the Season 22 premiere, but the series quickly dropped this thread. Then, in an effort to prove it really could live up to the promises of recognition and change that showrunner Warren Leight shared with The Hollywood Reporter in June of 2020, the series took the easy way out. Rather than imbue its detectives and their investigations with a greater degree of realism, it simply stopped showing them being detectives or engaging in investigations. This could have worked, but in the words of a Season 1, Episode 4 Captain Cragen (Dann Florek), "You take something away, it'd be nice if you had something to add."

SVU gutted its formula, then filled it with fluff

By adopting the "Law & Order: Criminal Intent" format of revealing the criminal from the outset and removing the element of mystery (as "SVU" now frequently does), the series avoids the potential for bad or idealized cop behavior. A detective can't, for example, be applauded for an unconstitutional search or interrogation if there is no search or interrogation. This cowardly exercise in avoidance inevitably meant that the provocative debates about the interpretation of legal precedent and prosecutorial approaches were similarly cut.

Unfortunately, the series has yet to replace its two most interesting and controversial aspects with anything other than a greater focus on the detectives' personal lives (e.g., more "Liv and Her Adorable Kid" scenes), or worse, a heavy-handed, repetitive promotion of its progressive stance on a headline. If even liberal viewers feels "SVU" has become, as one such fan wrote on Reddit, "a caricature of everything people hate about liberals," it is, in large part, because it has nothing else to portray. It's only in relief of the voids in its storylines that the series' long-held liberal views feel so foregrounded. Unfortunately, this foregrounding appears in its character development as well, homogenizing the squad's detectives to the point where they're nearly indistinguishable from one another. Seasons 22 and 23 brought this homogenization to a new level, while proving that "SVU" has lost all faith in its audience — a reality evidenced by its new-found insistence on telling, instead of showing.

It's no secret that much of the "SVU" audience is left-leaning, as studies from the Norman Lear Center have long-shown. One wonders just who, then, the series is attempting to convince when it consistently delivers episodes that — thanks to their trite and tidy, pandering half-plots — feel like lectures.

SVU went from preaching to the choir to talking to itself

There's a time and place for this blunt-force approach, and that time and place is in the 1980s, in the concluding scene of an after-school special. When one attempts to "tell" instead of "show" in 2022's technique-savvy, Platinum Age of Television, it's not only ineffective, but boring as hell.

After referring to recent seasons as "an overbloated and smug mess," a fan on the show's subreddit longed for the franchise's former complexity: "Even the plots ... based on real life events/stories [were] interesting and engaging," they wrote, "rather than just 'HELLO EVERYONE, HERE'S OUR DISCOUNT VERSION OF JEFFREY EPSTEIN WITH ABSOLUTELY NO NUANCE WHATSOEVER/OUR SHAMBLES OF AN EFFORT TO REFLECT ON BLM.'"

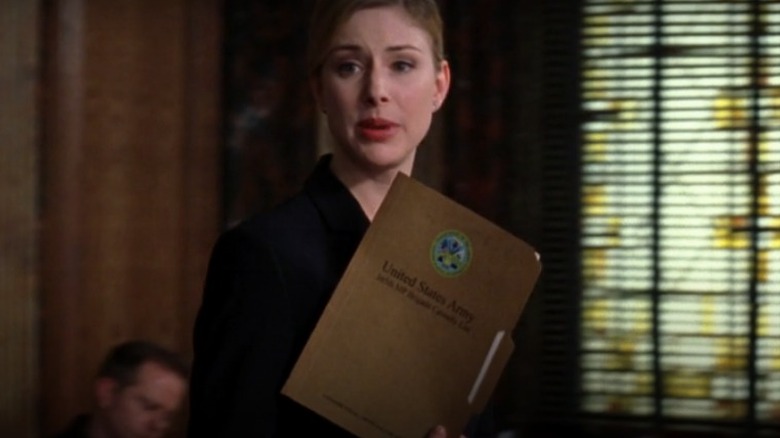

By contrast, watching Diane Neal's Casey Novak attempt to subpoena Donald Rumsfeld in Season 6, for instance, was both enlightening and compelling. So compelling, in fact, that The Cut's Opheli Garcia Lawler would write at-length about the episode fourteen years after it originally aired, saying "at 10, 'SVU' ... introduced me to the notion that the U.S. government is not super invested in the best interests of its citizens." The writer also noted that the episode "took the hideous, often insular, interpersonal crimes of our day-to-day lives and connected them to the larger systems that enable [them]."

The series did this sort of thing both effectively and quite frequently in its first 21 seasons, without having Benson bend over backwards to represent and clarify the episodes' theses.

SVU owes its viewership more than this

Prior to its empty new format, "Special Victims Unit" tackled a litany of hot button issues, from corrupt cops, to hate crime legislation, to systemic racism, classism, and misogyny, to the inability of the prison system to safely accommodate trans convicts, treat mental health, and ensure the safety of inmates. The detectives weren't always on the same side of these issues, and often had to "come around" to the stance the episode was putting forth. The new structure and its safe, myopic narratives, however, encourage the depressing, even dangerous approach to art that says the mere depiction of an opinion or behavior necessarily equals the promotion of that opinion or behavior. In reality, the only thing such a model promotes is a complete lack of critical thinking and audience engagement.

If Nouveau-"SVU" is a sign of things to come, we're fast-approaching an era wherein writers refuse to explore a controversial opposition, for fear they'll be accused of agreeing with said opposition. Not only does this make for excruciatingly banal storytelling, it hurts a story's ability to encourage thought, debate, and (ultimately) growth.

Until the series finds a way to inspire these things devoid of its investigate-and-prosecute/defend formula, it will continue to erode not only its own thematic intent and ratings, but primetime's approach to storytelling on the whole. Pretending we live in a just world isn't the same as arguing for one. In fact, it allows many viewers to think "all's well" in the world of law and order — ironically, the exact issue the series was attempting to remedy when it altered its format in the first place.