The Most Dangerous Films Ever Made

Most great artists would agree that suffering is necessary to create meaningful art, but only to an extent. A broken romance or two can encourage musicians and poets to mine the depths of their broken souls, for example, but it's doubtful anybody ever made a great record after getting mauled by a lion, or driving a truck off a cliff into the ocean. No, that type of suffering seems to be reserved exclusively for those whose art is the Hollywood film—and for better and worse, these movies were among the most hazardous ever to the health (and sometimes the lives) of cast and crew.

Waterworld (1995)

While it's seen today as something of a curiosity, it's easy to forget that 1995's Waterworld was seen both leading up to and after its release as a spectacularly misguided, perhaps career-killing failure for Kevin Costner. The most expensive film ever made at the time, it made less than half its budget back domestically (while still managing to turn a slight profit from overseas box office) while baffling audiences with its bizarre mythology and uneven tone. As might be expected from a film that takes place on a world covered in ocean, the seafaring shoot was more than a little hazardous, and nearly killed several cast and crew including its star.

Everyday unpleasantness included seasickness and constant jellyfish stings; one costly set sunk, and a diver nearly died of the bends during the retrieval effort. Female lead Jeanne Tripplehorn and child actress Tina Majorino had to be rescued by divers when their sailboat inexplicably fell apart, and Costner was pummeled by raging winds and seawater for over half an hour while suspended 40 feet in the air for a stunt (later telling a friend that he almost died).

Even one experienced stuntman—famous big wave surfer Bill Hamilton—was lost at sea while "commuting" to the shoot on a jet ski, and had to be rescued by a production helicopter. The entire shoot was one gigantic risk to life and limb, all for a film that introduced the phrase "pee-drinking man-fish" to the popular lexicon.

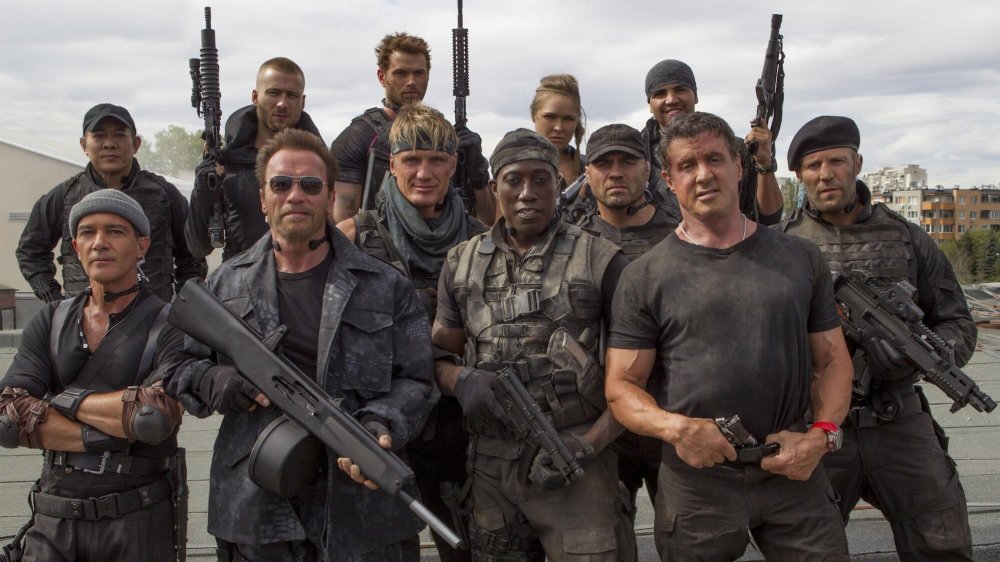

The Expendables 3 (2014)

Given the age of their casts, it stands to reason that the Expendables films have dished out a few injuries to its stars, and The Expendables 3 really seemed to have it in for its cast. Then 68-year old Sylvester Stallone suffered a scary fall that necessitated a metal plate in his back, joining the one in his neck from an injury incurred on the set of the first film, and co-star Antonio Banderas injured his knee in his very first take. But the production reserved its worst mishap for Jason Statham—who, fortunately, is apparently just as much of a badass off-camera as on.

Co-star Terry Crews recounted, "We were supposed to be on the back of this truck. For some reason, we're over there talking, sipping smoothies... we're in Varna in Bulgaria, on the edge of the Black Sea. He literally is supposed to stop the truck, we get out, we shoot, the whole thing. The truck doesn't stop. The truck goes over the dock, into the Black Sea with Jason Statham driving." At this point, everybody panicked—except Statham, who calmly swam to safety as the truck sunk into the depths.

Still, Statham told Jimmy Fallon that he wasn't nearly as calm headed as everyone thought, recounting what was going through is mind while underwater: "How am I going to get out of this? This is how it ends!" While Statham called it a "nightmare," instinct kicked in and he made it out safely. "Let me tell you something," Crews summed up, "Jason Statham is a true bad, bad dude."

Roar (1981)

If ever a film seemed specifically designed to threaten the safety of everyone involved, it is Roar, completed in 1981. It was the brainchild of actress Tippi Hedren and her writer/producer husband Noel Marshall, who conceived their story of a family attacked by wild jungle animals during a stay in Africa, and it was executed in the most insane fashion imaginable.

Dismayed to find that you couldn't actually rent lions, Hedren and Marshall bought a ranch and began raising their own—along with tigers, leopards, cheetahs, and even African elephants. Then they went ahead and shot their movie right there on the ranch, constantly surrounded by and working with some of the most incredibly dangerous animals on the planet. Even more shockingly, the young stars portraying the children of the family were the couple's actual children—Marshall's two sons and Hedren's daughter Melanie Griffith, only 17 when shooting commenced.

Throughout the ordeal of a shoot, the injuries piled up. Hedren was bitten on the head by a lion, and Marshall was bitten so many times he developed gangrene. Griffith received stitches to her face and almost lost an eye after an attack, and cinematographer Jan DeBont almost lost his entire scalp to a lion, an injury requiring over 200 stitches. Many of the attacks (and actual bloodshed) made the final cut, which wasn't given any kind of North American release until 2015. Years later, Hedren estimated the number of injuries at "over 100" and called Roar "the most dangerous film ever made in history."

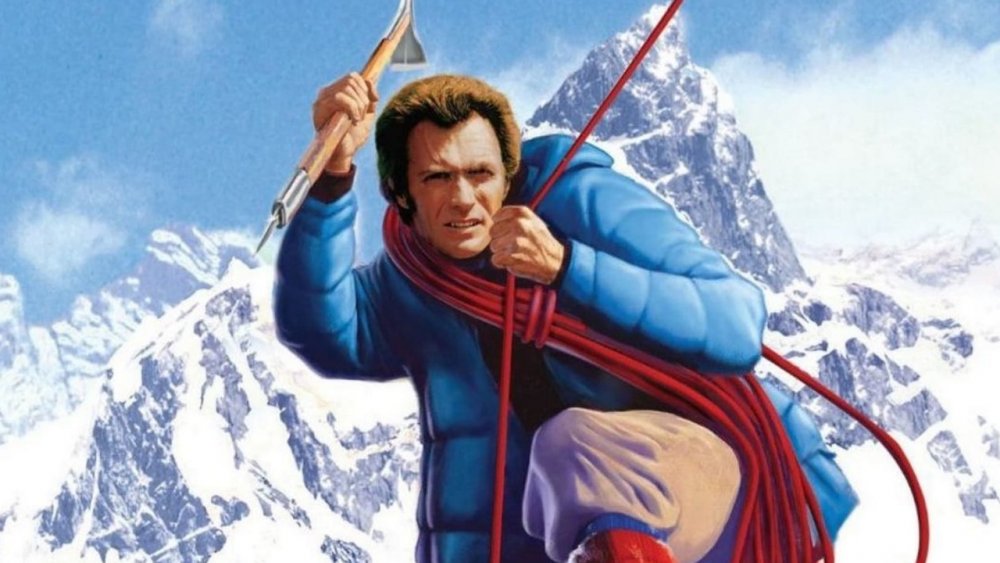

The Eiger Sanction (1975)

Clint Eastwood's third directorial effort, The Eiger Sanction (adapted from a popular novel of the same name) tells the familiar story of a retired assassin called back to do one last job—only this job takes place on the infamous north face of the Eiger, a 13,000-foot mountain in the Swiss Alps. The film was shot on location, so production was bound to be dangerous—and Eastwood and his crew didn't shy away from taking chances.

This is illustrated nicely by one insane risk taken by Eastwood himself, to get a shot in which his character dangles thousands of feet above the ground. As he described to the great Roger Ebert shortly after the film's release: "I didn't want to use a stunt man, because I wanted to use a telephoto lens and zoom in slowly all the way to my face—so you could see it was really me."

Later in the shoot, climbing advisor Mike Hoover was supervising a shot of some falling rocks on the north face when a huge boulder dislodged, killing stuntman Dave Knowles and showering the crew with smaller rocks, resulting in serious injuries to Hoover. Eastwood considered canceling the shoot, but was discouraged by the remaining stuntmen—all experienced climbers who didn't think the added element of film cameras made their dangerous sport any more dangerous, and who didn't want their colleague to have died for nothing.

Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983)

One of the most infamous on-set deaths in modern times occurred on the last scheduled day of filming for 1983's Twilight Zone: The Movie. Actor Vic Morrow and two child actors aged 6 and 7 were killed in an accident that received all the more attention for its outlandishly grisly nature: a helicopter crashed on top of them, crushing one of the children and decapitating the other one along with Morrow.

The horrifying accident was the result of improperly timed special effects explosions combined with the helicopter flying too low. In an incredibly rare case of a director facing criminal prosecution for events that took place on a film set, Landis and four others—including the special effects supervisor and the pilot of the helicopter—were charged with (and later acquitted of) involuntary manslaughter, and studio Warner Brothers settled civil suits by all three families out of court.

Incredibly, not only was the film still released, but the segment featuring Morrow (who gives a brilliant performance) was retained and even given the lead-off position in the four-segment anthology film. Of course, the scene featuring the helicopter was omitted.

Troy (2004)

The 2004 war epic Troy—with its $175 million budget—was one of the most expensive, lavishly staged films to ever be so indifferently received. Its domestic box office was paltry, and critical reaction was squarely in the middle of the road. It's mostly remembered today, if it's remembered at all, for the strange death of one of its stunt performers and for one of the most coincidental injuries in film history.

During a crowd scene in which a civil suit later alleged that extras were given unclear instructions, stuntman George Camilleri leapt into a crowd and sustained a severe injury to his lower leg. A couple weeks after surgery he was re-admitted to the hospital, and two days after that he was dead of a pulmonary thromboembolism—common after an injury of his type.

The film's star Brad Pitt, cast as Achilles, also somehow managed to injure his character's namesake tendon during the shoot, causing production to be shut down for ten weeks. The film had other obstacles to production, as well—Hurricane Marty, for instance, which damaged some sets, and a group of six employees of the production (security guards, no less) who were arrested for ripping off tools and a motorcycle from producers. But Troy overcame all of these difficulties and arrived triumphantly in theaters, to be met with a solid shrug.

Jumper (2008)

The set for the poorly-received 2008 sci-fi thriller Jumper didn't lash out until principal photography had wrapped, but when it did, it was deadly. Set dressers were hard at work tearing down exterior sets in the middle of a cold Toronto winter while the rest of the cast and crew were off to Tokyo for a few location shots, when a freakish mishap occurred—a huge chunk of sand and earth which was frozen to a wall came unstuck, striking three set dressers and killing one.

The 56-year old David Ritchie was instantly killed, and another man sustained serious injuries to his head and shoulders; the third was relatively unharmed. Toronto police described it as a "fluke accident," and the death cast a pall over the highly anticipated film, which unfortunately turned out to be awful.

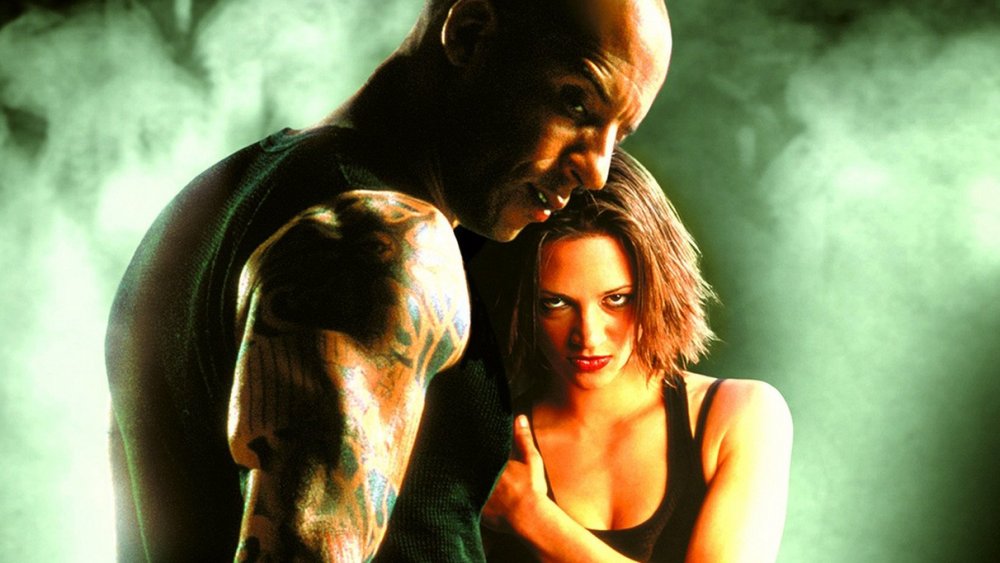

xXx (2002)

It goes without saying that xXx was a dangerous film to make; they should have just given Crazy Stunts second billing to Vin Diesel in its promotional material. The story of an extreme sports badass who becomes a secret government agent ramps up the danger factor with each successive stunt, and one spectacular set piece—in which Diesel's character Xander Cage ziplines down the cable towing his paraglider, barely making it underneath an oncoming bridge and landing on top of a moving boat—cost aerial stunt coordinator Harry O' Connor his life.

According to director Rob Cohen on the DVD commentary, O'Connor's stunt remained in the completed film. He can be seen performing the zipline stunt, and the scene cuts away at just the moment he's about to pass under the bridge—because unlike Xander Cage, O'Connor didn't clear the structure. The 45-year-old former Navy SEAL collided with a pillar at high speed, breaking his neck and dying instantly.

Unbelievably, the fatality occurred on the second take, with the first going smoothly, and neither Cohen nor Diesel were even present. Cohen considered the stunt to be so routine that he assigned it to his second unit, and most of the cast and crew had already completed their work on the film.

Resident Evil: The Final Chapter (2016)

They've never scored big with critics, but the Resident Evil films have certainly been reliable moneymakers over 15 years and six entries—it's the most profitable video game-to-film series adaptation of all time. Resident Evil: The Final Chapter was the lowest-grossing to date, serving only to bring the series to a close so it can be fitted for a James Wan-produced reboot—but the production proved to be just as big a threat to life and limb as the film's roving zombies.

Stuntwoman Olivia Jackson suffered horrific injuries when a camera rig failed to make way for her during a motorcycle stunt, requiring her to be put into a medically induced coma. Writing for Glamour UK, she remembers: "My face was degloved (when skin is torn from the underlying structures) and the artery in my neck severed... [my sister] saw my teeth where my cheeks used to be. Morphine numbed the pain of my shattered shoulder blade, severed crown, collapsed lung, brain bleed and broken clavicle, ribs and vertebrae." Her left arm was also paralyzed, and eventually had to be amputated.

Unfortunately, the incident didn't seem to lead to increased caution on the set. Only a couple months later, crew member Ricardo Cornelius was crushed to death when a Humvee slipped off a rotating platform and pinned him to a wall. Reports of the accident leaked only after the film had completed production.

The Hangover Part II (2011)

The set of a screwball comedy might not seem a likely place for dangerous mishaps, but while shooting The Hangover Part II on location in Bangkok, stunt coordinator Russell Solberg made a serious error that altered the life of stunt performer Scott McLean forever.

McLean, the stunt double for Ed Helms, was shooting a scene in which he sticks his head out the window of a moving truck and is narrowly missed by an oncoming car. The shot required precision timing, and according to a subsequent lawsuit filed by McLean and his wife, Solberg altered this timing right before rolling the cameras, directing "the driver of the automobile in which plaintiff Scott McLean was a passenger, that the speed of his vehicle be increased significantly to a speed unsafe for the stunt, thus resulting in a major collision."

McLean sustained massive head injuries and had to be airlifted to an Australian hospital to treat brain trauma. He has since had to relearn how to walk and talk, which doctors initially thought might not be possible. To add insult to literal injury, the sequence was not only kept in the finished film, but the very shot that devastated the life of McLean and his family was actually used in the trailer. McLean eventually dropped his lawsuit against Warner Bros., and the terms of their settlement were not disclosed.

Apocalypse Now (1979)

Perhaps no film shoot was as legendarily taxing on everyone involved as Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now; that nobody died during filming is nothing short of a miracle. Shooting on location in the Philippines, the production was beset by cast changes, tropical diseases, and natural disasters that wiped out entire sets, but those were the least of its problems—because Coppola was running a drug-fueled, psychologically abusive madhouse that was out of control from the very beginning.

Lead actor Martin Sheen, replacing the fired Harvey Keitel, stepped straight into the worst possible environment for him at that time. In the middle of a personal breakdown and mired deep in alcoholism, Sheen was fed a steady diet of alcohol and abuse by Coppola, who brought out the darkness in Sheen's character by screaming at the actor and telling him how evil he was.

Sheen would eventually have a heart attack, yet somehow continued on with the production. Coppola lost 100 pounds and threatened to kill himself three times. Dennis Hopper stumbled through the shoot on a daily regimen of a case of beer, half gallon of rum, and three ounces of cocaine, and actor Sam Bottoms spent the entire shoot—which ended up taking over a year to complete—tripping on LSD. Coppola would later say "We had access to too much money and little by little we went insane," while Hopper commented, "Ask anybody who was out there, we all felt like we fought the war."

The African Queen (1951)

The African Queen is a classic, one of the greatest movies in the filmography of venerable director and actor John Huston. Tired of the phony look of Hollywood's jungle sets, Huston decided to use his experience shooting The Treasure of the Sierra Madre—which he had filmed on location in Mexico—and apply it to his new adventure, which was to be filmed over seven weeks in Uganda and the Congo. Years later, star Katherine Hepburn would write a book entitled The Making of The African Queen: or, How I Went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall, and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind, which should give you a pretty good idea of how this went.

While not dodging crocodiles, snakes, and disease-carrying mosquitoes, cast and crew spent their time in between takes puking their brains out due to dysentery, the result of drinking contaminated water (Hepburn even had to have a bucket nearby at all times). The only ones who were unaffected were Huston and star Humphrey Bogart, simply because neither of them drank any water—they both preferred whiskey.

Bogart would later say, "All I ate was baked beans, canned asparagus, and Scotch whiskey. Whenever a fly bit Huston or me, it dropped dead." They may have been miserable off-camera, but it all worked out onscreen. Hepburn and Bogart both received Oscar nominations for their roles, and Bogart won—the only win of his career.

Ben-Hur (1959)

1959's Ben-Hur is well-known for its chariot race scene, and with good reason. The scene was filmed on the largest set ever constructed at that time, covering 18 acres. It was also at the time the most expensive single scene in history, shot for $4 million—a quarter of the budget—over ten grueling weeks. The action-packed sequence was virtually unprecedented in cinema, employing a "camera car" that put viewers right in the middle of the chaotic, horse-drawn action. It certainly looks incredibly dangerous onscreen, but that's only because it absolutely was.

The scene in question involved several spills, crashes, and pileups that had to be orchestrated flawlessly—and remarkably, for the most part, they were. The only real injury sustained during the shooting of the scene remained in the finished film, and serves to illustrate just how dangerous the shoot was.

At one point, Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) runs over a crashed chariot and is pitched over the front end of his own, managing to hang on and regain control. The stunt was performed by stuntman Joe Canutt, who landed so hard that he really was pitched violently off the chariot and in between its two horses. He sustained only a cut on his chin, but to this day, rumors persist that studio MGM covered up the death of a stunt performer on Ben-Hur—simply because it's so hard to believe nobody died filming that scene.

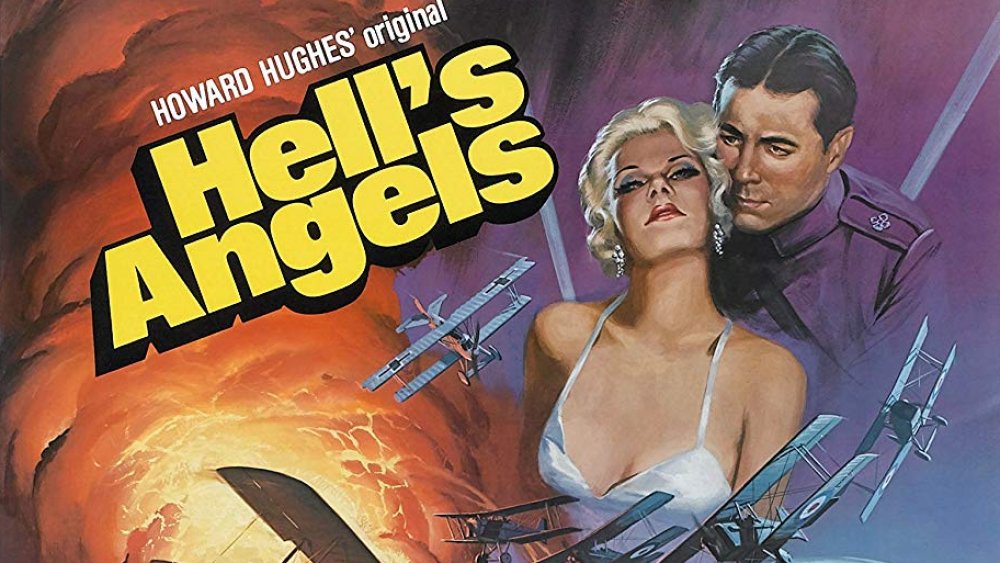

Hell's Angels (1930)

Famously insane rich man Howard Hughes was fascinated with Hollywood for his entire life, and he had the kind of cash and notoriety to make his Tinseltown dreams a reality. He began producing films in 1926 and amassed a somewhat impressive Hollywood resume over 30 years, but he only wrote and directed one feature himself—1930's Hell's Angels, a World War I flying ace drama. Hughes was, of course, a legendarily fearless aviator and for this film he assembled the world's largest private air force (87 fighter planes) and a phalanx of skilled pilots to perform its dogfight scenes. Filmed less than three decades after planes were invented, the scenes are indeed spectacular—but they came at the cost of three crew members' lives and Hughes' face, which he rearranged attempting a stunt that one of his pilots balked at for being too dangerous.

Over a year and a half into production, Hughes was growing frustrated. Although he had some incredible footage, crew members were beginning to revolt, with some outright refusing to perform the stunts Hughes was calling for (the deaths of two pilots and a mechanic to that point had made them understandably jumpy). One such refusal so enraged Hughes that he climbed into the cockpit of a fighter to perform the stunt himself—only to crash in a nearby field, suffering a major concussion and cuts all over his face. It was Hughes' first plane crash, but as anybody who has ever seen The Aviator knows, it was not his last.

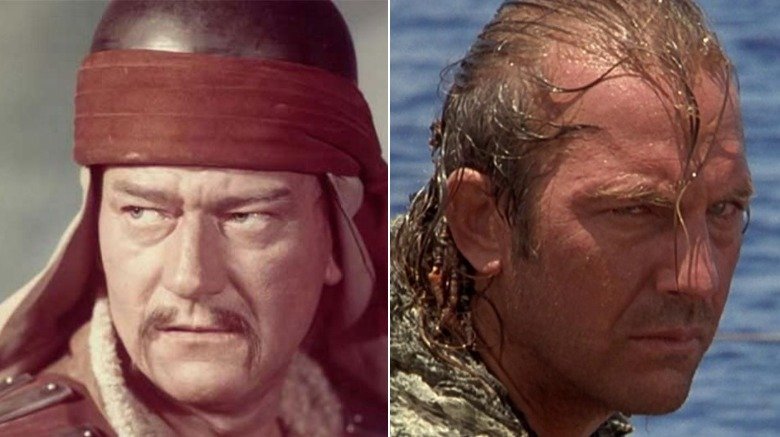

The Conqueror (1956)

The second-to-last film produced by Howard Hughes would haunt him for the rest of his life for more than one reason. It was a gigantic boondoggle, a big-budget flop featuring a woefully miscast John Wayne as Genghis Khan that often played as unintentional comedy. During the last years of his life, Hughes bought up all the prints he could find and watched the film obsessively—perhaps mortified by its failure, or perhaps racked with guilt for having basically killed the entire cast.

The film was shot on location in the Utah desert, directly downwind from the area where the US government detonated over 100 atomic bombs between 1951 and 1962. Eleven were detonated in 1953 alone, the year before The Conqueror began production. The risks of nuclear fallout were not terribly well-understood at the time, and the Atomic Energy Commission declared the area (and the nearby town of St. George) completely safe. They were staggeringly, horrifyingly wrong.

In the decades following The Conqueror's production, no fewer than 90 cast and crew died of cancer, most likely due to radiation exposure while on set—including Wayne, lead actress Susan Hayward, and director Dick Powell. A subsequent study concluded that Cold War-era nuclear testing had killed at least 11,000 Americans and since 1990 Congress has paid $2 billion to residents of the very fallout area in which The Conqueror was filmed. It was one of Hollywood's biggest turkeys, it killed one of its biggest stars, and it just may have finished the job of driving Howard Hughes totally insane.