The Ending Of Arrival Explained

Based on the 1998 short story "Story of Your Life" by Ted Chiang, Denis Villeneuve's sci-fi drama Arrival earned nearly universal critical praise thanks to Amy Adams's brilliant performance, Villeneuve's excellent direction and the film's mature, focused take on the extraterrestrial genre. Effectively combining tense and thrilling situations with absurdly good sound design and an intellectually stimulating plot, the film earned numerous awards and is widely regarded as one of 2016's best movies... but that doesn't mean it isn't confusing. In fact, Arrival's focus on linguistic principles and space-time theory is tough to untangle, and only seems to get more complex the deeper you dive into it.

But don't worry! We've got you covered. Here's everything—and we mean everything—you need to know about Arrival's confusing ending. And of course: spoilers!

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

Discussed briefly in the middle of the movie, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis—known also as linguistic relativity or Whorfianism—is actually the very foundation upon which Arrival is built. In order to even begin to comprehend the ending of Villeneuve's film, we must first understand the linguistic theory behind it all.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis holds that our perception of reality is either altered or determined by the language we speak. For example, you've probably heard somewhere or another that Eskimos, because they live so intimately with snow, have developed a lot of words to describe it. Therefore, their perception of snow must be more refined than most everyone else's. This was actually an example put forth by Benjamin Whorf himself, though its merit has sparked a contentious debate among linguists ever since.

Another simple example of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis in action: the Hungarian word for "raccoon"—an animal that doesn't exist in Central Europe outside of television and zoos—is "mosómedve," which literally translates to "washing bear." The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis might thus argue that Hungarians fundamentally view the curious, touchy-feely creature differently than those who simply refer to it as a "raccoon," despite the fact that the English word derives from Native American words meaning essentially the same thing. (None of which are entirely dissimilar to "trash panda.")

Now, with the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis in mind, let's take a look at how exactly linguistic relativity influences Arrival...

Rewiring Louise's brain

Arrival doesn't simply make use of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. It pushes the strongest version of linguistic relativity—which states that our reality is determined by our language—to its most extreme limits.

Dr. Louise Banks' job is to, first and foremost, find out why the Heptapods came to Earth. In order to do so, she enters into an intergalactic language exchange, trading English vocabulary for the same words in the Heptapods' dictionary. As the spearhead of these language lessons, Banks is the one who first begins to truly learn and comprehend the Heptapod's strange, non-linear mode of communication. Thus, she's also the first to perceive reality, space, and time as the aliens do—as per the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. In short, her brain gets totally rewired.

Said rewiring begins roughly 51 minutes into the film, after she teaches the Heptapods her and Ian's names. While dissecting some printouts of the alien language, she has a vision of her daughter playing with a caterpillar in a field—a moment easily dismissed as a random memory. However, these presumed flashbacks of her daughter intensify and appear more frequently as she learns more of the Heptapods' language, leading viewers to initially presume Banks is simply overworked and suffering from exhaustion. It isn't until the end—when Banks asks the Heptapods "who is this child?"—that we understand something significant has happened to Banks' brain.

'Mommy and Daddy Talk to Animals'

The film begins with a brief and emotional recollection of Louise's daughter's all-too-brief life, during which we sadly learn that she passed away from disease when only in her teens. What we aren't told, however, is that the birth of Banks' daughter actually takes place after the events of the film.

In fact, we're intentionally misled into thinking Banks' daughter's death is the reason the college professor is single and seemingly depressed. We're also tricked into thinking Banks' visions of her daughter are memories—which makes sense, since the majority deal with very specific instances, such as when Hannah shows her the television show she created for school, titled "Mommy and Daddy Talk to Animals," or when she explains to her daughter that her father left because he was angry about something Louise told him. (More on that later.) The film's biggest plot twist comes when we discover that none of these supposed memories have actually happened yet.

As Louise discovers, the ability to view time in a non-linear fashion has been bestowed upon her by the Heptapods. Because their language is non-linear, with no definitive beginning or end, their perception of reality is also non-linear—allowing them to see both the past and the future. Meanwhile, we lame humans are stuck with more limited languages and linear perceptions of time... at least, until the Heptapods arrive.

The purpose of the Heptapods' arrival

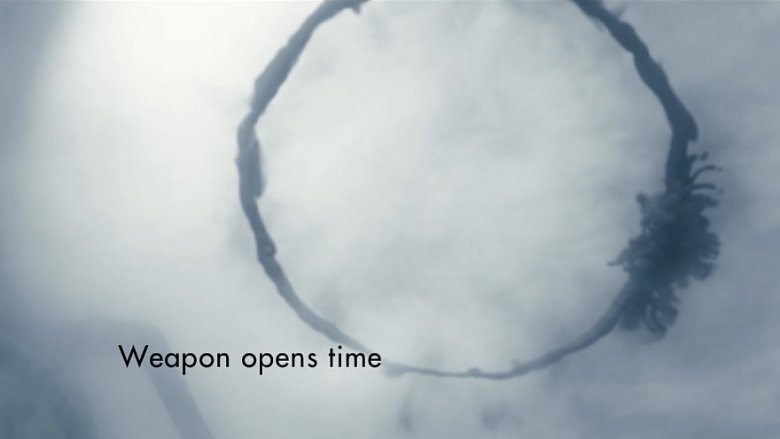

Dr. Banks' job is to, first and foremost, find out why the Heptapods came to Earth. With China and Russia ready to blow the alien spaceships out of the sky, Banks is constantly pressured to pop the question, despite her reservations that both species' limited knowledge of each other's language may lead to misinterpretation. Which is precisely what happens: when finally asked, the Heptapods reply that their purpose on Earth is to "give weapon," creating an international crisis on a global scale.

However, as Banks suspects, the aliens really mean to "give tool." They simply haven't learned the difference between the two words yet. Furthermore, the tool the Heptapods wish to grace humanity with is their language—a vital necessity if the Heptapods are to survive extinction in 3,000 years, at which point they claim they'll require humanity's assistance. In other words, they're trying to keep us around long enough to help them way down the road... but how can their language do that?

As the Heptapods so graciously spell out for our protagonist: "Louise sees future" because "Weapon opens time." Since by "weapon" they mean "tool," and we know that their language is said tool, we thus realize that anyone who knows their non-linear language interprets time non-linearly. Basically, if you speak Heptapodian, you know the future—the most extreme version of the Safir-Whorf hypothesis imaginable.

So Louise can see her future child... great. How is that supposed to help the Heptapods survive in 3000 years? Just how strong is this "weapon"?

The future can inform the present

Here's where things start to get tricky.

After Dr. Banks learns the truth about the Heptapods' language and the future-seeing gifts it bestows, she's still the only one who can see time non-linearly. With the world on the brink of war and ready to open fire on the peaceful aliens, nobody's really got time to listen to Louise's crazy theories.

However, with all seemingly lost, Louise suddenly has a vision taking place 18 months in the future. In it, she finds herself at a gala celebrating the unity of the world powers—an unlikely scenario, given that the Chinese General Shang is ready to ignite the powder keg at any moment. Bizarrely, Shang approaches Dr. Banks at this future party, and personally thanks her for calling him on his private number and convincing him to stop the attack 18 months prior by uttering Shang's wife's dying words. Of course, there's no way Louise could possibly be privy to this information, so future Shang gives future Louise his private number and tells her the magic words at said future gala—thus also imparting the knowledge onto present-day Louise.

The big question here, though, is how could future Shang possibly know to give future Louise this secret information 18 months after the fact? The answer isn't so simple...

Backward causation

This is where the power of the Heptapods' language really starts to smell fishy. Because Shang has also learned the Heptapods' language over the 18-month span from having his finger on the big red WWIII button to the celebratory gala, he has therefore also gained the ability to see time non-linearly, just like Louise. With this gift of both foresight and hindsight, future Shang understands the absolute necessity of giving future Louise his private number and wife's dying words upon their only meeting at the future gala, thus providing present-day Louise with the ability to convince present-day Shang to stand down.

Is your head spinning yet? Let's simplify it.

You're surely familiar with the basic principles of causation. For example, you put water and grounds in your coffee maker and turn it on. We'll call this Event 1, which takes place at 8AM, or Time 1. Wait a little bit, and you've got freshly brewed coffee (Event 2) at 8:05AM (Time 2). One event caused the other future event. Simple, right? What transpires in Arrival is the same thing, just in the reverse. It's actually called "backward causation" or "retro-causation," in which Event 2 (Shang at the gala) causes Event 1 (Louise saves the day).

Obviously, it sounds like fiction, but this is a movie about octopus-like aliens. So what we want to know is: could this all really work, hypothetically and theoretically speaking? Well, that all depends...

Presentism and Eternalism

Not all philosophical discussions of time and space would allow for the complicated backward causation of Arrival to take place. For example, some space-time theorists who believe in Presentism—which states that only objects in the present exist—would rule out the possibility of future Shang ever informing present-day Louise, as future Shang doesn't exist. In fact, the past also doesn't exist. The only thing that exists is the present, so future Shang helping present-day Louise save the day is simply an impossibility.

Eternalism, however, would definitely allow for the unbelievable retro-causation of Arrival to take place. According to this form of 'non-Presentism,' objects in both the past and future exist to the exact same degree as objects in the present, like three lines running side by side. As explained by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Eternalism holds that both Socrates and future Martian outposts exist at this very moment, despite the fact that neither is currently present. Just because you can't see the past nor the future doesn't mean they don't exist. By this philosophy, future Shang could definitely help present-day Louise save the Heptapod species and prevent a potential World War III.

Okay, so Arrival takes place with an Eternalistic viewpoint. That's settled. So it's all good, right?

Not quite.

Does Louise even have free will?

As is often the case with anything pertaining to time travel—or, in this case, time manipulation—there's one major problem with Arrival's backward causation: what if present-day Louise chose not to call General Shang?

Just because we assume time follows an Eternalist view—where the past and present both exist just as much as the future—doesn't necessarily mean that future is one in which Shang gives his digits to Louise. In order for that specific future to exist, Louise would have to follow through by choosing to complete the time loop. She would have to call General Shang. If she didn't—which is entirely within the realm of possibility—the future gala Louise experiences wouldn't exist. However, since this future is shown to already exist, that would imply that Louise didn't have a choice in the matter. Nor did General Shang have the choice to ignore Louise's call, or simply tell her to shove off.

So here's the kicker: According to Arrival, everything is predetermined. Its principal actors, from the Heptapods to Dr. Banks to General Shang to Louise's daughter, are all slaves to a pre-ordained metaphysical destiny. Every action has already been planned, and every choice is already decided. In fact, there is no choice. There never was. For Arrival to work, free will would have to be an illusion.

Aside from being an absolute downer, the illusion of choice in Arrival's universe also presents another major problem.

The curious case of Louise's daughter

The first visions of the future experienced by Louise are that of her future daughter. From the very beginning of the movie, we learn that she tragically dies from a rare disease—a fact confirmed later in one of Louise's visions. In that same vision, Louise explains to her daughter why the child's father left: "It's my fault. I told him something that he wasn't ready to hear. Believe it or not, I know something that's going to happen. I can't explain how I know. I just do. And when I told your dad he got really mad, and he said I made the wrong choice."

Knowing what we already know, this confession isn't terribly difficult to unpack. Despite being gifted with the knowledge that her child would contract a rare disease and die, Louise chooses—as we witness in the final scene—to have a baby with Ian Donnelly, without sharing that tragic knowledge with him. Donnelly thus leaves the family out of anger. But did Louise really have any choice at all?

We're led to believe that Louise made the conscious decision to have a child, despite knowing the heartbreaking pain that would follow. But as we already discovered, technical and head-spinning difficulties within Arrival's space-time mechanics would suggest that Louise never actually had a choice...though she probably didn't know it. For a predetermined future to exist to the extent that it can inform the past—which is certainly the case in Arrival—Louise never had any choice at all.

A pro-life movie?

Of course, when evaluating the ending of Arrival, it would make sense to ask the director what he thinks. As it turns out, he claims the characters in the film do all have free will—which has caused some to view the movie as a pro-life statement.

"In the short story, the idea is that the Heptapods see life like a [scripted] play," Denis Villeneuve explained to The Verge." They know what will happen, so they have the choice—either they do it bored to death, or they embrace it and try to be at their best, like an actor on a stage. For me, the idea that everything is written in front of us is not necessarily appealing. But what appeals to me is the idea that through our intuition, we kind of know things in advance a little bit. That's very mysterious for me, that we try to repress those instincts. But being in contact with our finality, and being more in contact with our nature, I think we'll find that humility, and I think that human beings are lacking humility right now. We are trying too much to control nature."

None of that means Villeneuve intended to make a pro-life statement with Arrival. "I was honestly afraid that because of the nature of the story, it could be seen as a pro-life movie, which is not for me," the director said. "The idea that the movie would be seen as pro-life would be sad for me, because I respect life, but I believe a woman must have her freedom."

Do linguists buy it?

To bring it all back full circle, let's finally examine whether the film's cornerstone—rewiring the brain via the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis—would really work.

Betty Birner, a professor of linguistics and cognitive science at Northern Illinois University, isn't buying it. "At one point in the movie," Birner recalled to Slate, "the character Ian [Jeremy Renner] says, 'The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis says that if you immerse yourself in another language, you can rewire your brain.' And that made me laugh out loud, because Whorf never said anything about rewiring your brain. But since this wasn't the linguist speaking, it's fine that another character is misunderstanding the Sapir-Whorf ... No linguist would ever buy into the notion that the minute you understand something about this second language, get sort of a lightbulb going off, and you say, 'Oh my gosh, I completely see how the speakers of Swahili view plant life now.' It's just silly and its false." Alas, there go our dreams of a real-life Heptapod encounter gifting us with the power to see the future.

Nevertheless, the film is still a good time, even for a hardcore linguist. "It was a ton of fun to see a movie that's basically all about the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis," Birner said. "On the other hand, they took the hypothesis way beyond anything that is plausible."