What Lincoln Doesn't Tell You About The True Story

Abraham Lincoln may seem like an impossibly towering figure to portray in cinema. He's widely regarded as the best president in American history for leading the country through the Civil War and abolishing slavery (via C-SPAN). He is arguably a figure more mythical than any of the founding fathers of the United States, despite their century-long head start on his accomplishments. Steven Spielberg decided to tackle this legendary subject in his 2012 film "Lincoln." Spielberg made a wise choice in narrowing the focus of the film to the last few months of the Civil War and Lincoln's first term in office, as he and his administration made an extraordinary effort to pass the 13th Amendment of the Constitution.

Free of the burden of telling an entire life story, "Lincoln" allows Spielberg and Oscar-winning star Daniel Day-Lewis to fill up a short time span and humanize Lincoln as a rambling, eccentric statesman, who deals with very human sorrow and frustrations, all while achieving such legendary things. The movie does a wonderful job of making otherwise dry and dense congressional proceedings easy to follow and compelling, and it was generally well-received by historians and critics alike. However, in addition to the small inaccuracies and anachronisms that are inevitable in a period piece, "Lincoln" also omits some historical facts and makes wholesale changes to others in the pursuit of dramatic tension. This is what "Lincoln" doesn't tell you about the true story.

It's unlikely soldiers knew the Gettysburg address by heart

"Lincoln" takes place in 1865, two years after Abraham Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address, his most famous speech and perhaps the most known in American history. Not surprisingly, the movie includes a reference to this short speech, which starts with the highly quotable line that "four score and seven years ago" the Declaration of Independence was signed and "dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal" (via Britannica). "Lincoln" begins with two young soldiers quoting this speech back to President Lincoln, who is visiting the front lines in the last year of the Civil War.

While it's a compelling and symbolic scene (one soldier is white and the other Black), it also exaggerates how well-known and revered the Gettysburg Address would have been during the war, or even for several decades afterwards. Writing in The Daily Beast, historian Harold Holzer points out that it is "almost inconceivable that any uniformed soldier of the day (or civilians, for that matter) would have memorized a speech that, however ingrained in modern memory, did not achieve any semblance of a national reputation until the 20th century." It may be taught in classrooms and carved into the wall of the Lincoln memorial today, but in the 1860s, the Gettysburg Address was only preserved in a few people's memories and newspaper clippings.

No one would have called it the 13th Amendment

Language can be the trickiest thing to portray in historical fiction. For every glorious use of 19th-century language in the film — such as Lincoln referring to expensive "flubdubs" to decorate the White House or exclaiming "buzzard's guts!" in frustration at his cabinet — there are small anachronisms that historians love to nitpick. Checking the script against historical databases for The Atlantic, professor Benjamin Schmidt found plenty of common phrases that weren't in use at the time, like "peace talks," "bipartisanship," and even the simple affirmative "yeah."

But the biggest linguistic difference comes up over and over, as it concerns an essential element of the plot: No one would have referred to the key legislation as "the 13th amendment." "At the time," Schmidt writes, "people just said the 'constitutional amendment' or the 'slavery amendment': It had been 60 years since the last amendment, and no one was in the habit of numbering them." We see this in practice to this day: 27 amendments to the Constitution have been ratified, but we call proposed new ones — like the Equal Rights Amendment – by name instead of "the 28th amendment." Doing so is like counting your chickens before they're ratified by two thirds of state legislatures, so to speak.

Willie wasn't the only son that the Lincolns had lost

One of the more compelling sub-plots of "Lincoln" centers on the President and First Lady's concern for their eldest son Robert, who wants to join the Union Army before the war ends. We discover that their reluctance to allow him to do so, as well as their indulgence of their younger son Tad, results from the death of their other son, Willie. He passed away three years before the film's events at the age of 11, so with the war nearly over in 1865, you can understand the Lincolns' reluctance to risk the life of another son in battle.

While the film doesn't shy away from the reality of the Lincolns' grief, it does omit another heartbreaking fact: Their second son, Eddie Lincoln, passed away in 1850. He was almost four-years-old and most likely died from tuberculosis, according to Lincoln historian Roger J. Norton. While it's reasonable that it wouldn't come up in dialogue 15 years later, it's an important bit of historical context that lends weight and understanding to the bitter, anguished fight that the Lincolns have over Robert's decision.

Mary Todd Lincoln was more than just a spectator in politics

With so much time devoted to the nuances of congressional procedure, "Lincoln" pares other aspects of history down to the footnotes, and no one suffers more from this than Mary Todd Lincoln (played by Sally Field). Her scenes in the movie focus heavily on her well-known penchant for melancholy after the death of her son Willie, her recurring headaches, and general moodiness. While this is all drawn from well-documented history, Mary was also much more complex figure than many have been led to believe, and she was integral to the equally moody Abraham Lincoln's political drive and ambition (via Ohio State University).

When the Lincolns first married, they were such an odd pair that many assumed it was a marriage of political convenience. Mary was instrumental in approving her husband's political appointments, and would likely have had a much more nuanced take on the 13th amendment's chances than her skeptical response, which is shown in "Lincoln." During the Civil War, she spent just as much time visiting the wounded and fund-raising for their care as she did throwing elaborate White House functions. All in all, she was defined by much more than the grief and gloom that "Lincoln" focuses on.

James Ashley played a much bigger role

Some of the biggest liberties that "Lincoln" takes with history are its dramatizations of the debate over the Amendment to abolish slavery in the House of Representatives. These scenes form the spine of the film, and contain a lot more shouting and back-and-forth bickering than the actual records show (via The Library of Congress). Additionally, the role of Thaddeus Stevens has been vastly expanded in "Lincoln." In the film, Tommy Lee Jones plays Stevens, the imperious chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, who is all but the spokesperson for the entire abolitionist faction of the House.

As seen in the transcripts of the debate, it was actually Ohio representative James Ashley, who was essentially the quarterback for the 13th Amendment's victory. He introduced the amendment itself for debate, and as the House Majority floor manager, he did much more of the impassioned speaking in the weeks before its passage. Tommy Lee Jones notwithstanding, it would have been fun to see character actor David Costabile (best known as the nebbish Gale Boetticher in "Breaking Bad") with a more substantial showcase as Ashley in Spielberg's representation of these events.

A major Thaddeus Stevens scene didn't actually happen

One of the most tense and climatic scenes in "Lincoln" is when Thaddeus Stevens shockingly softens his staunch abolitionist position and claims that he does not hold that African-Americans are equal "in all things," but merely "before the law." However, it is probably the least accurate scene in the movie. According to The Blog Divided at Dickinson College, this comes after another completely fictional scene, where the President convinces Stevens not to take such a hard line on abolition. While screenwriter Tony Kushner is including semi-accurate material to get at how many pragmatic compromises it took to get the 13th Amendment passed in the face of so much opposition, he also plays fast and loose both with the timeline and tone of the debate.

In reality, Stevens made this remark three and a half years earlier in July 1861, when the legality and morality of slavery was a lot touchier than in the waning months of the Civil War that are the focus of "Lincoln" (via American Heritage). It was part of a strategy to not alienate the slave-holding Union border-states in the tenuous beginning of the conflict. Stevens and the rest of the Radical Republicans hardly minced words in condemning slavery during the actual debate in January 1865. With the North's victory inevitable at that time, the spirit of the day wasn't as compromising as it once was.

The Confederate envoys didn't represent real hope for peace

One of the major sources of tension in "Lincoln" is timing: The President must get the 13th Amendment passed before anyone learns that the Confederacy has already sent out envoys for potential peace talks. A key dramatic moment involves a real message that Lincoln sent to the congressional floor, where he obfuscates his knowledge of any such envoys by noting how they weren't technically "in Washington." But "Lincoln" rearranges the timeline drastically, and significantly overplays how likely peace with the Confederacy actually was.

In reality, the Confederate delegation was first approved in December 1864 rather than in January 1865 (as shown in the film), and the envoys were on the road to D.C. for a few days before the Amendment's passing (via The Blog Divided at Dickinson College). There were several stages to these peace talks, in which journalist and advisor Francis Preston Blair Sr. met with Confederate President Jefferson Davis twice. The film speeds up this timeline for dramatic effect, and perhaps more inaccurate is its representation of the likelihood of peace between the North and the South by 1865. The North's conditions for peace would have involved abiding by the Emancipation Proclamation and freeing all slaves, while the South's conditions would have involved not doing so, so peace talks were all but hopeless. And in a sign that many historians believe signals he wasn't serious, Davis sent his Vice President Alexander Stephens — known as a critic of his policies — as the head of the delegation. So, the dramatic stakes of "Lincoln" rely on something that would have been a small wrinkle in the actual debate.

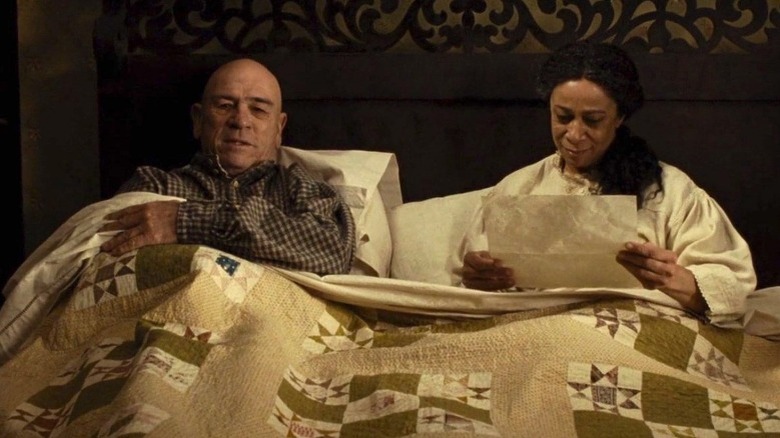

Thaddeus Stevens and his housekeeper's relationship

While a domestic romantic relationship between Thaddeus Stevens and his mixed-race housekeeper Lydia Hamilton Smith has often been suspected by historians, currently no evidence or public admission of such a relationship exists. According to the History of American Women Blog, Smith ran Stevens' household for 25 years and helped him raise his two orphaned nephews, but the Congressman claimed there was "no foundation" to rumors that she was more to him. Nonetheless, "Lincoln" shows them getting into bed together in a heartwarming moment near the film's end.

While this is a happy ending of sorts, it also adds a speculative personal motivation to Stevens' lifelong abolitionism. And it nearly goes without saying, but it's even more unlikely that right after passing the 13th Amendment, any member of Congress would be allowed to "borrow" it and return it in the morning, as Tommy Lee Jones' Thaddeus Stevens does.

The attempt on Seward's life isn't mentioned

Even though "Lincoln" is loosely based on Doris Kearns Goodwin's 2005 book "Team of Rivals," the only "rival" Lincoln incorporated into his cabinet who plays any prominent role is Secretary of State William Seward. Seward was a key part of Lincoln's push for the 13th amendment's ratification, and plays an intermediary between Lincoln and his backroom-dealing lobbyists in the film. It makes it strange, then, when Lincoln's assassination at the film's conclusion is depicted without even a passing mention of the simultaneous attempt on Seward's life on the same day (via History.com).

Granted, it may have been awkward to insert a last-minute mention of it in the brief scene of the reverent mourners gathered at the President's bedside. But since the majority of "Lincoln" is concerned with the nuts and bolts of policy-making, wherein Seward plays such a prominent role, it's disconcerting when the movie shifts to a more simplistic view of the assassination, which disregards the larger plot to kill others in Lincoln's cabinet. In reality, Seward, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and future President Ulysses Grant were all potential targets of a larger conspiracy to assassinate prominent figures in Lincoln's government.

African-Americans played an active role that the movie doesn't show

Perhaps of all the historical inaccuracies of "Lincoln," the biggest and most glaring omission is the film's failure to show how African-Americans were in many ways agents of their own liberation. As historian Katie Masur wrote in The New York Times, "it's disappointing that in a movie devoted to explaining the abolition of slavery in the United States, African-American characters do almost nothing but passively wait for white men to liberate them."

White House maid Elizabeth Keckley gets only a brief moment of agency when she excuses herself from the proceedings after Thaddeus Stevens sells out slaves' humanity, but this is a fictional moment. In reality, Keckley and another White House servant, William Slade (also shown in the film), were leaders of a "highly politicized" community of free African-Americans in the nation's capitol during the time period shown in "Lincoln." Keckley was an organizer and leader, who helped find resources for runaway slaves, while Slade was active in the Social, Civil and Statistical Association, which was an early civil rights organization. While "Lincoln" tracks the efforts of dozens of white politicians as they work to pass the 13th Amendment, the film ignores the very real activism of its only prominent Black characters.