The Ending Of Disappearance At Clifton Hill Explained

Albert Shin's 2019 film, "Disappearance at Clifton Hill," may be a run-of-the-mill, pulp-inspired (if not wholly infused) trope-heavy twist end mystery thriller, but it's one that makes a daring attempt to deliver a much more poignant commentary than its genre typically allows. Every decision made in the film — from its trapped-in-time setting to its central protagonist's particular psychosis to the mechanics by which the small cast of characters move through the world and interact with one another — serves first to reveal and then to reiterate Shin's two primary and interconnected concerns.

Those are as follows: One, that despite our internet-driven, increasing obsession with uncovering the capital T "Truth" behind the true-crime phenom or conspiracy du jour, that already elusive truth has become even more unobtainable (ironically, as a result of the same technology that feeds the obsession); and, two, that our hypocritical nostalgia for "simpler times" is driven around an imperfect (at best) and illusory (at worst) recollection of those times.

The back cover rundown of Shin's film (co-written by James Schultz), is about as straightforward and seemingly unoriginal as they come, though this too proves itself intentional by the end of the film. In fact, the ending of "Disappearance at Clifton Hill" goes a long way toward justifying some of the film's seemingly strange-for-the-sake-of-strange elements.

Shin's movie doesn't need much to lure us in

In the movie, Girl Who Doesn't Have Her Life Together (Abby, portrayed by Tuppence Middleton), is prompted by her mom's death to return to her hometown outside of Niagara Falls where, as a child, she secretly witnessed a violent kidnapping. Sibling Who Does Have Her Life Together (Laure, portrayed by Hannah Gross, of "Mindhunter") has what turns out to be a justifiably complicated relationship with her sister, and doesn't exactly welcome her back with open arms. Abbey is dismayed to learn that Small-Town Evil Rich Bigwig (Charlie Lake, portrayed by Eric Johnson) has purchased her deceased mother's motel out from under her, so she teams up with the Small Town Conspiracy Theorist and Local Historian (Walter, portrayed by David Cronenberg) to solve the now decades-old mystery in which she believes Lake played a major role. Eventually, she does solve it. Except, she maybe doesn't. Myth and illusion permeate the film on both a literal and metaphoric level.

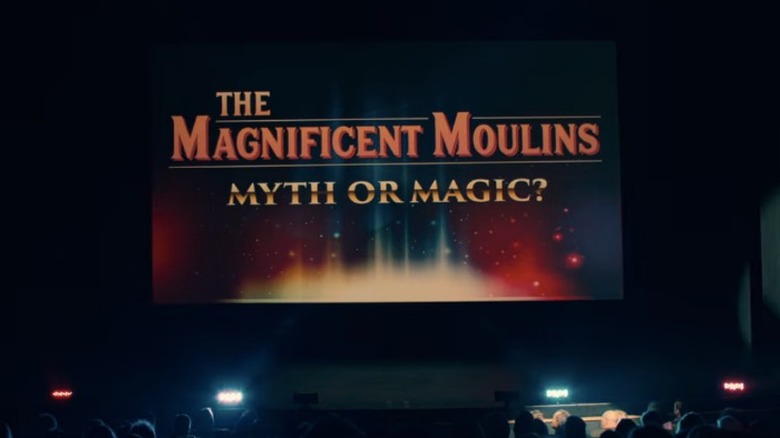

Abby learns with the help of Walter, a local podcast host and Falls diver, that the abduction she witnessed was that of Alex Moulin (Colin McLeod), the young child of a pair of local magicians called The Magnificent Moulins. Though the boy's body was never found following his disappearance, his death is ruled a suicide, and he's said to have fallen into the local gorge. The plot thickens, and Abby (and the viewer) dive in with both feet.

The twist in Disappearance at Clifton Hill comes in waves

After following a trail of "Twin Peaks"-meets-Serial clues, Abby discovers and ultimately convinces the police that Lake molested the boy, then paid his parents and their tiger tamer to get rid of him (which they do by feeding him to their tiger). All's well that ends well, Alex gets justice, and Abby gets to keep her motel. Unfortunately, as the final scene reveals, she may have misinterpreted a few things.

In the last scene, Abby checks in a guest (Aaron Poole) who — just like the abused boy she witnessed from afar on that cloudy day in her childhood — has a patch over one eye. Though the film stops short of verifying that the man is Alex Moulin, we're clearly meant to believe he is. He points to the newspaper on the desk, whose front page contains a story about Lake's arrest, and casually tells her, "you know...he's not lying." When she asks if Lake hurt the boy, he says, "no...he saved his life."

On the surface, Shin's twist appears to be just that: a simple "gotcha" moment that complicates how we feel about a protagonist whose victory we were championing just moments before. But like everything else in "Disappearance at Clifton Hill," this, too, isn't exactly what it seems.

Shin's end note is a doozy

As we learn and witness repeatedly throughout the film, Abby doesn't just struggle with the truth — she's a pathological liar. Prior to her homecoming, she spent several years in Arizona conning a local social worker. The "cycle," as her sister refers to it, cost Abby's mother (literally) dearly, forcing her to have to sell the motel. The audience learns this fairly late in the story, and Abby's seeming uncovering of the truth feels like redemption.

In the final few seconds of the film, after Abby appears initially distraught by the revelation that she's just sent an innocent man to prison, we see her watch her reflection in the mirror (a tangible form of the truth twice-removed). It's a subtle, blink-and-you'll-miss-it moment, but her frown begins to curl into a smile as she — and the viewers — realize she's relieved, even happy, to be a part of a lie. The scene is punctuated by an old song crooning, suddenly and from somewhere unseen, "sometimes, I get so lonely, sometimes, I feel so blue..."

Abby (a journalism student, it's worth noting) never really wanted to find the truth. She wanted to sift through a game of potential truths and illusions in order to occupy the void that compels her to lie on a pathological level. That's exactly what she does, and what the viewer does with her, throughout the film. Its one of the many ways in which Albert Shin makes his commentary on today's "true" crime-obsessed society known, and that commentary is delivered as much by what he doesn't show as what he does.

Disappearance at Clifton Hill is partially an indictment

The internet, for example, appears only briefly, on a rather dated library computer; Walter has a podcast, but we never see anyone listening to it on a device; Abby records her meeting with The Magnificent Moulins on an old-school tape recorder, not a smartphone (in fact, no smartphones are seen in the film), and was it not for the mention of Abby being 7 years old in 1994, we'd have a hard time telling when the narrative takes place. The motel aesthetic falls somewhere in the late 60s-to-early-70s, the VHS tapes Abby watches on her quest are so '80s they'd fit in perfectly on the set of "Stranger Things," and Abby repeatedly meets people in mid-century mod diners. Abby's sister works security at a casino, but even her eye-in-the-sky cameras and TVs feel somewhat out-of-date.

By leaving all things ultra-modern and high-tech out of his film, Shin is at once drawing our attention to them and suggesting that our nostalgia for a "kinder, simpler" time is misplaced. Our abundance of access to often unverifiable information (not to mention the litany of true crime documentaries and series) may make half-truths, illusions, inaccurate depictions, or tantalizing gossip spread faster than ever before, but society has always had an insatiable need to feed on and insert itself in juicy headlines. What's more, by tricking us into rooting for and sympathizing with an unreliable protagonist, Shin prohibits us from engaging in any form of exceptionalism. We're no better than Abby, the film suggests, and that's about the only thing we can know for sure.