Why Ryan Gosling's Lowest Rated Rotten Tomatoes Movie Is Worth Watching

Content warning: This film involves the topic of suicide.

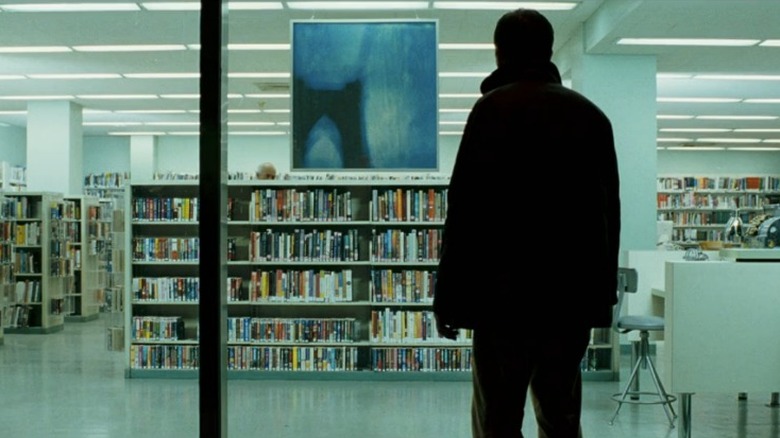

If David Benioff were looking to redeem himself after the largely-despised series finale of "Game of Thrones," he might do well to remind audiences that he wrote the 2005 thriller, "Stay." That the film, Ryan Gosling's lowest-rated movie on Rotten Tomatoes, is a veritable orgy of early 2000s nostalgia (e.g., the butterfly clips, the low rise cords and graphic tees, the sheer amount of hair product and the alt-rock typeface and filters) would be reason enough to give it another chance.

That said, to reduce Benioff and director Marc Forster's highly-stylized film to a collection of such dated elements is a mistake. While plenty of late-90s, early-00s thrillers and action movies relied heavily on this kind of gloss-grunge, music video varnish — "Stigmata," "In Dreams," "Murder by Numbers," "Domino," and the original "Saw" among them — Forster uses these things with far more purpose, and with an impact and intent that becomes clear only in the film's twist ending.

Throughout the film, we watch as determined psychologist Sam (Ewan McGregor) struggles to help his patient Henry (Gosling), who tells him he plans on dying by suicide. Sam's wife Lila (Naomi Watts) offers her husband and former doctor some insight, having previously been in Henry's state of mind herself. After a while, Sam is confronted with events, interactions, and scenes that don't quite make sense, but are credible enough to make him question his own reality. The film's ending delivers a pretty gutting explanation for all this, but it isn't this expertly-executed twist that makes "Stay" worth watching — instead, it's the hidden second twist in its artfully-executed Rorschach test of a thesis.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Stay feels stale only in hindsight

In 2022, it's easy to take endings like that of "Stay" for granted. On the other side of "The Sixth Sense," "Fight Club," and "Shutter Island," films with an ending whose pivotal revelation fundamentally re-contextualizes everything the audience just saw are no more unexpected than their now-anticipated endings. To watch "Stay" in 2022 is to know, 10 minutes into the film, that a major movie twist is coming. But if you're able to put yourself back in the film's original context, before the language and trickery of this type of film became so commonplace, you'll find that Benioff's twist isn't the point his film, but a demonstration necessary to relay that point.

Like "Jacob's Ladder" before it and like "The Life Before Her Eyes" after it, the ending of "Stay" reveals that its entire narrative was nothing but the imagined, last life flash of a dying brain. Unlike these films, however, "Stay" uses its central protagonist's extended hallucination to highlight an almost unacceptably tragic reality. That is, that for all our understanding of ourselves as the center (if not the hero), of our own lives, when it comes to our deaths, we have no say, control over, or place in the narrative. In fact, on a literal, biological level, we're not even in the scene. As Gosling's Henry lays dying in the middle of a bridge after having been thrown from a vehicle, his instinctual, neurological need to turn the moment's chaos and arbitrariness into an ordered narrative with meaning, purpose, and intent, is (at first) a stark reminder of just how much of the so-called meaning, purpose, and intent in our lives is an illusion.

Stay touches on something universal to our species

Henry imagines he dies by suicide (and that the collection of bystanders surrounding him in the road are characters in his mental health journey) because the reality — that his tire simply and randomly blew out, causing his car to spiral out of control — takes him out of the narrative of his own death. Importantly, the film at no point suggests that suicide is an answer to our powerlessness — if anything, it uses the arbitrariness of death to argue for a more intentional approach to life.

As Roger Ebert writes in his glowing review of the film, "It is the record of how we deal with the fundamental events of life by casting them into terms we can understand [...] all arranged so they seem to add up and lead somewhere. Maybe they don't. But the mind is a machine for making them seem to."

On a biological, fundamental level, "Stay" reminds us, we need a story. Stories were the most efficient way for our caveman brains to remember things (e.g., "don't go in there — remember what happened to your friend Grunt Sound?"), and they remain our most important tool for extracting meaning from, or injecting meaning in, the meaningless. It's the same reason we see faces in inanimate objects, patterns and political conspiracies in mere coincidence, build religions around characters, and (rather harmfully and inaccurately) couch a cancer patient's, depressive's, or addict's experiences with their respective disease as a "battle." We need a protagonist, an antagonist, and a structure to make sense ofthe chaos of reality, particularly when that chaos poses a threat over which we have little control.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Stay asks us to think, and that's okay

In one of the film's more heavy-handed scenes, Sam watches Henry's girlfriend (who, in reality, has just been killed in the car accident) rehearse a scene from "Hamlet" from increasingly odd angles. The take-away for the audience isn't "to be or not to be" (that infamous line that implies we have some choice or role to play in the matter), but the equally infamous, "there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so."

"Stay" doesn't tell us whether its ultimate message is good or bad. Like the best horror films and the too-often least critically-lauded films (critics gave it a 27% on Rotten Tomatoes) it simply delivers it, and allows the viewer's subjective response to do the rest.

In an era absolutely saturated with brightly-colored, CGI-tastic stories that repeatedly — and, almost exclusively — tell us the many ways in which "good" inevitably triumphs over "bad" (despite all evidence to the contrary in our reality), "Stay" is worth watching if only for its bravery. A film bold enough to suggest that the idea of a "just," orderly, or causation-driven world is not only a fallacy, but a figment of our imagination driven by a biological imperative, is a film worthy of our attention. But if you're interpreting this film's message as a source of dismay, or merely representative of the general malaise of the Emo Era, you're missing one of Benioff and Forster's more romantic, downright Fitzgeraldian winks.

Stay echoes one of Fitzgerald's most romantic sentiments

It's no accident that the twist allusions in "Stay" are painted with a forceful, Godard-meets-David-Lynch brush. While many a critic couldn't resist taking the bait and drawing the directorial comparisons (see: James Berardinelli's review), audiences — who gave it a 70% on Rotten Tomatoes — appear to have seen something more. Its focus on art is overt, at times clumsy, and wholly un-subtle, because this reveals the film's more sneakily optimistic subtext. The jump cuts, variations in focus, jarring repetitions, surrealist scene framing, and repeated references to artists (as well as characters who are struggling artists) all serve to highlight that subtext.

In "The Beautiful and Damned," (via Goodreads) three of F. Scott Fitzgerald's characters attempt to philosophically one-up one another, in a dialogue that plays out as follows:

"Dick: (Pompously) Art isn't meaningless.

Maury: It is in itself. It isn't in that it tries to make life less so.

Anthony: In other words, Dick, you're playing before a grand stand peopled with ghosts [...] it being a meaningless world, why write? The very attempt to give it purpose is purposeless."

It's an obviously ironic, borderline meta scene, and one that "Stay" embodies almost verbatim. The dialogue would not exist if Fitzgerald believed that the attempt was purposeless, just as "Stay" would not exist if its creators believed their surface-level thesis. Herein lies the true point behind Benioff's film (a thematic twist to accompany its plot twist), and the heart that its critics failed to see.

Refreshingly, Stay trusts its audience

Maybe the "meaningful" narratives we imagine our lives to be are nothing but an illusion, and a creative construct of the mind. But if that's the case, why not create as intentional and poignant a life as possible? "Stay" reminds us that our lives, even (and especially) at their most seemingly beautiful, would be little more than bad art (a concept referenced and represented repeatedly in the film) without our ability to imagine and mold them into something more. Subsequently, it gives us a pretty damn good incentive to live intentionally, and to create and embrace meaningful art, since both the death at the end of that intent — and the life that creates and embraces that art — are, in and of themselves, devoid of both. Our deaths may be arbitrary, even (literally) accidental, as Henry's is, but up until the moment where our brain fully dies, we're capable of creating meaning, and of finding purpose, in a meaningless, purposeless existence.

"Stay" is by no means a perfect film, nor is it streaming-franchise-superhero-spin-off-sequel-world-build-worthy. It's also not, given the abundance of films with similar plot mechanics, all that original in its story or structure. But it does do something that today's most popular cinema, to an increasing degree, appears wholly uninterested in even attempting. It shows and tells us one thing while asking us, while trusting us, to see and hear another. And if for no other reason than that it feels good to be trusted, and to be encouraged to create and derive our own meaning and purpose, "Stay" is a film worth watching.