Things You Only Notice The Second Time You Watch Planes, Trains And Automobiles

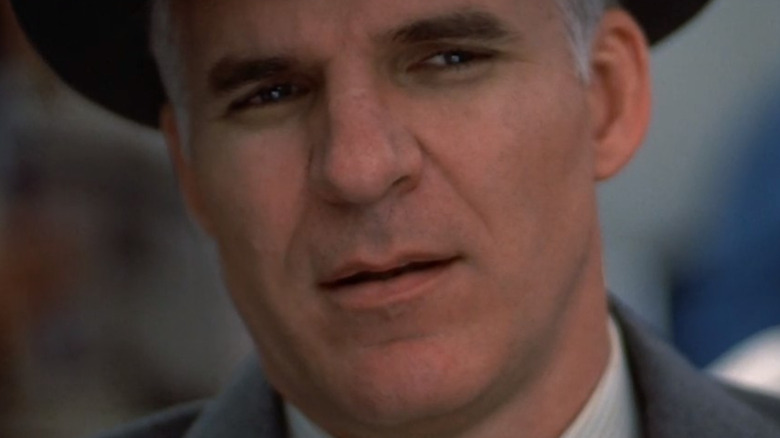

"Planes, Trains and Automobiles" doesn't get mentioned among the all-time classics often, but maybe it should. Writer/director John Hughes' story of executive family-man Neal Page (Steve Martin) and his disastrous attempts to make it home for Thanksgiving — sometimes helped and sometimes hindered by loudmouthed traveling salesman Del Griffith (John Candy) — has all the ingredients of a GOAT film. It's got subtle pleasures and simple ones. Hughes throws every possible and impossible obstacle in front of his long-suffering heroes, but he still grounds it all in their well-realized personalities, so much so that you get to feel you know them by the time the credits roll.

"Planes, Trains and Automobiles" never goes long without making you laugh out loud, but it's not just a joke machine either. Hughes' attention to character, helped by two of the era's biggest stars giving possibly their best performances, makes for a powerful mix of comedy and tragedy — but it doesn't become clear just how powerful until the end.

The last-act revelation changes everything that came before it. Maybe Hughes knew what he was doing when he set the story at Thanksgiving, making it an annual tradition for many families. After all, if you only see it once, you might miss half the story, and the film is rich enough to never wear out even if you watch it year after year. Here are just a few things we've found watching this comedy a second time. This article contains spoilers.

John Hughes sneaks in a preview for his next movie

Neal's trip home is doomed from the first frame. To start, his last meeting of the day runs late, forcing him to race against rush-hour Manhattan traffic to get to his flight on time. This means facing off with another professional type for one of the dwindling number of available cabs. Neal's opponent should look familiar to film fans — in fact, he ranks alongside Martin and Candy as the biggest star in the movie. That's Kevin Bacon, star of "Footloose," "Apollo 13," "X-Men: First Class," and countless other films. What's he doing in such a small role? Well, Hughes' next movie a year later would be the Bacon-starring "She's Having a Baby." Maybe he was trying to build a John Hughes Cinematic Universe? Or trying to boost the whole cast's Bacon Number?

Well, the real answer is much more prosaic. Bacon explains in "Getting There Is Half the Fun: The Stories of 'Planes, Trains and Automobiles'" that he enjoyed working with Hughes so much, he told him, "If you need a bit part, an extra, anything, just give me a call."

That's not even the only connection between the two movies. In one scene, Neal's wife Susan (Leila Robbins) is staying up late watching a movie where you can hear Bacon arguing with Elizabeth McGovern. Audiences at the time wouldn't be able to see the significance until the next year, but she's somehow managed to tune into "She's Having a Baby." How it's on TV before it even came out is anyone's guess. Maybe the Page family sprung for the "Rick and Morty" interdimensional cable package.

Del ruins Neal's trip before they even meet

Neal and Del first meet when the traveling salesman thoughtlessly takes a cab Neal had just spent over $100 bribing another traveler to let him take. "You stole my cab!" Neal snaps when they meet again in the airport, but that's not the only cab Del made Neal miss that day.

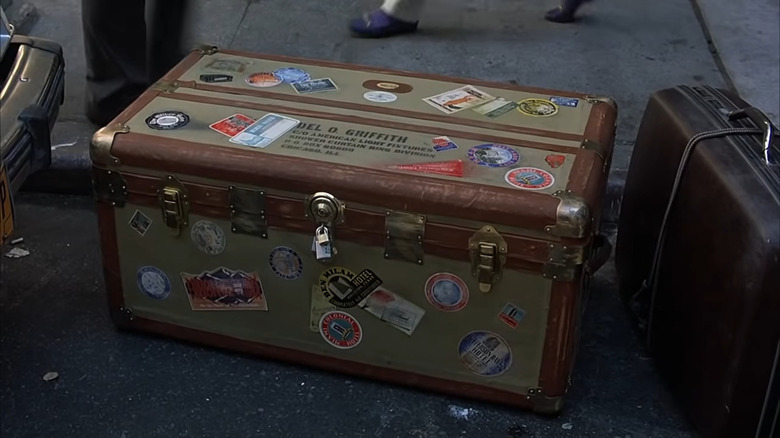

Neal's chase against Kevin Bacon comes to an abrupt end when he trips and falls on a giant, anachronistic steamer trunk. On your first viewing, that might just seem like a random obstacle. But if you've seen the movie before, you and that trunk should be well acquainted since it's the same one Del effortfully schleps all across the country, squeezing it in the backs of cars and the overhead compartments of buses. It's basically as big a character as our two protagonists, and thanks to its awkward size, Del has jinxed Neal's trip before the two have even met.

The sad truth of Del's giant trunk

The best reason to watch "Planes, Trains and Automobiles" a second time is to watch it transform before your eyes into a whole different movie now that you know how it ends. As the odd couple finally part ways on the Chicago El, Neal looks back on his eventful trip and realizes the secret Del kept from him. Coming back to the station he just left, Neal finds Del's still there, and the salesman confirms the truth: His beloved wife Marie has been dead for eight years, and he's been homeless ever since.

It's a classic last-act twist, but it doesn't come out of nowhere. You can see Hughes laying the groundwork from the beginning, starting with that trunk that serves Del in place of an introduction. Like any good buddy-comedy pair, Del and Neal are defined by contrast. Neal keeps to himself while Del treats everyone he meets like an old friend. Neal has an expensive tailored suit, and Del has a variety of baggy, mismatched outfits straight out of the thrift store. And while Neal carries a small, sensible briefcase along on his trip, Del continues dragging that monster of a trunk around, sometimes literally, no matter what.

But once you know the truth, it becomes more than a wacky comedy prop. Del needs that trunk because he's carrying everything he owns with him. If it seems to be the size of a house, that only makes sense because it's the closest thing Del has to one.

The 'those aren't pillows scene' turns tragic the second time you see it

If there's one thing in "Planes, Trains, and Automobiles" that hasn't aged well, it's ironically what was once its signature scene — the "those aren't pillows" moment. The DVD even comes in a "Those Aren't Pillows Edition."

Neal and Del wake up horrified to realize they may have gotten accidentally intimate during the night ("Where's your hand?" "Between two pillows." "Those aren't pillows!") and try to reclaim their manhood by immediately changing the subject to football. It's a classic "gay panic" gag, a one-time comedy mainstay that's grown progressively more uncomfortable over the years.

But if it no longer works as comedy on first watch, it still plays like gangbusters as tragedy on a rewatch. Cuddled up with Neal, with his dead wife's portrait on the bedside table, Del looks the happiest he does in the whole movie. Before his rude awakening, he's likely dreaming he and Marie are together again. No wonder it takes so long for Neal to wake him.

Neal sees Del in two places at once

John Hughes doesn't often get mentioned among the great film stylists, even if he can take some comfort in knowing the average film fan is more likely to know his name than, say, Jean Luc Godard's. Part of that is because he made the kind of crowd-pleasing Hollywood comedies that generally don't need much style as long as the jokes land. If anything, though, he deserves more credit for not using that an excuse and deploying film language to economically develop story and character.

For example, we already know the whole plot of the movie in the first scene without Steve Martin saying a word, just by the juxtaposition of his plane ticket, his fidgety impatience, and his indecisive boss. And there are more obviously stylized moments too, like the cartoon logic of the car crash scene where Martin and Candy briefly turn into bug-eyed skeletons.

Other touches are less obvious. When Neal meets Del in the airport, there's a brief flash of him in the stolen cab, efficiently setting up their conflict in under a second. It's so efficient it may take a second viewing to realize how complex this scene is. This isn't just a flashback. We're seeing inside Neal's head as he pieces together that the man sitting across from him is the same one who stole the cab, with the cab door in front of Neal while the airport's still in the background.

Even inanimate objects can tell jokes

One of the great joys of watching and rewatching "Planes, Trains and Automobiles" is John Hughes' attention to detail. Every extra seems to have their own little story, and every highway and hotel will be immediately familiar to anyone who's endured a road trip like Neal and Del's. We could spend a whole article just unpacking all the gewgaws and doodads littering the pimped-out cab Martin and Candy take from the Wichita airport.

Then there are the details that are there just as a private joke to reward the audience for paying attention. It's easy to get caught up in the story, after all, especially in a pivotal scene like the one where the ticket agent announces all flights have been canceled. But it's worth looking past him to the destination board in the background for a sly little visual joke. Just in case there was any doubt where Neal and Del are headed, the placard reads "Destination: Nowhere."

Planes, Trains and Automobiles is an unofficial Ferris Bueller reunion

"Planes, Trains and Automobiles" was a bit of a departure for John Hughes, who'd carved out his niche in Hollywood as the ultimate high school director. Still, as he began courting an older audience, Hughes never forgot the people who brought him there, which might explain why the cast lists for "Automobiles" and "Ferris Bueller's Day Off" look so much alike.

The stars from "Bueller" start appearing early, with Lyman Ward, aka Ferris' dad, as one of Neal's coworkers at the ad agency. Then Ben Stein — whose trademark drone drilled "Bueller? Bueller?" into a generation's memory — appears as the ticket agent announcing the bad news about Neal and Del's flight.

Most memorably, we have Edie McClurg, who'd already deployed her pitch-perfect Midwestern mom accent to an incongruous string of then-current teen slang as Principal Rooney's assistant in "Bueller." She's even more unforgettable in "Automobiles" as the car rental agent, following up Steve Martin's profanity-filled tirade with a single F-bomb — one that lands with such hilarious impact it's one of the few that deserves the name.

The movie gets the formula confrontation out of the way early

"Planes, Trains and Automobiles" remains a classic long after so many of its contemporaries are forgotten because while they all offer more of the same, John Hughes' film provides something heartfelt and unique. "Automobiles" may fit into a number of classic Hollywood formulas — the holiday movie, the slobs vs. snobs movie, the road movie, and the mismatched buddy comedy. But whether it's a friendship or romance, every Hollywood comedy needs to throw a wrench in the relationship somewhere around the 90-minute mark with a big emotional confrontation. They say formulas stick because they work, but this one rarely does. Too often, it's a sudden spike in emotional stakes in a movie that previously had none, and it's hard to get invested when the couple's reunion is such a foregone conclusion.

Hughes seems to have known this because he moves the obligatory confrontation from the end to the beginning. After all, if you were Del, would you really be able to make it through a whole trip with Neal before you blew up at him? Granted, there are multiple smaller confrontations over the course of the film as Neal tries and fails to separate himself from Del. But with the big one out of the way, the movie's free to focus on letting the characters' relationship develop naturally and on the truly unnatural string of disasters the story throws at them. And when they finally do reconcile in the end, it's that much more meaningful.

The odd extras

It should be clear by now that "Planes, Trains and Automobiles" is a tightly made film, where every filmmaking choice serves the overall story. But at the same time, it's full of details that serve no purpose except to make the character's world feel like more than a flat backdrop for their antics. "Automobiles" stands out from the hundreds of other road movies because it really feels like Hughes is giving you a tour of the road from Wichita to Chicago. This isn't some generic backlot recreation of the American Midwest. Every frame is packed with local color, odd enough to give the film's world a lived-in specificity but not so much it becomes exhaustingly quirky.

One example in particular stands out. After their train breaks down, Del and Neal find themselves in the waiting room of a bus station next to an old man straight out of a hillbilly postcard with a long beard and a shoebox full of mice. Who is he? What is he doing there? The movie never stops to explain, which only seems right. After all, how many strange characters do we run into in real life with just as little explanation?

The TV reveals Neal could've made the flight after all

Neal and Del's trip is such an ordeal they probably wish they'd never gone through with it in the first place. So it's probably for the best they didn't keep tabs on the news of their flight, or they would realize they never had to. Attentive viewers, on the other hand, should be able to put it together.

Just as Neal is suffering through what he thinks will be the low point in his trip, sharing a beer-soaked mattress with Del (who's as noisy sleeping as awake), there's a brief shot of his wife, Susan, asleep in front of the TV. While she's unconscious, she misses the news that "traffic has resumed at O'Hare airport." So after the rush to get a motel that got the mismatched traveling partners stuck together, Neal could've made his flight after all if he'd just hung tight in the airport a few more hours. Considering how much worse his journey gets from there, it's probably for the best he never found out it was all for nothing.

Del and Neal's second night sharing a hotel room is the opposite of their first

Like any good buddy comedy, "Planes, Trains and Automobiles" is about bringing two totally opposite characters together. But there are other, subtler pairs of opposites that can subconsciously affect your response to the movie, even if it takes a couple of viewings to consciously recognize them.

For instance, Neal and Del's disastrous road trip is bookended by two motel stays — first, when Del buys a room for an unwilling Neal, and second, when Neal willingly invites Del in out of the cold. This gesture of kindness shows how far their relationship has come, and director John Hughes solidifies that impression with an infectiously joyful scene of the pair joking, laughing, and drinking together. Their lively dialogue parallels Neal's earlier monologue about all the reasons he hates Del. On their first night together, Del buys himself a beer and spills it all over the bed, leaving poor Neal to spend the night in a puddle of alcohol. On their last night together, they share drinks from the minibar, about as old a symbol of friendship as you could ask for.

The last piece of parallelism is pure visual storytelling, letting the setting influence our response to the action. The first motel room is dingy and cramped, with a cold color scheme that reflects Neal's cold attitude. The last motel room is done up like a cozy log cabin, with the warm browns of the wooden walls and furniture saying just as much as any of the dialogue.

Del and Neal drive past Chicago

Before they finally reach home, Neal and Del get turned around on the highway, leading to a car crash most action movies would kill for when they meet two trucks driving the opposite direction. And that's before a match in the seat sets the whole car on fire. They still manage to stagger into a motel, but if you're watching closely, you might see they never get themselves reoriented.

"Automobiles" has another minor role for a major star with Spinal Tap member and future "Better Call Saul" star Michael McKean as a state trooper, who pulls them over for speeding. (Del explains he couldn't tell because the speedometer melted.) In "Getting There Is Half the Fun," McKean explains why he took such a small role: It wasn't small when he took it. As he put it, "It was supposed to be quite a bit longer because I bring with me a piece of exposition, which is that ... they have gone 100 miles past Chicago."

But McKean can still fill that role in the final cut if you're paying close enough attention. McKean's patrol car and shoulder patch identify him as a Wisconsin state trooper — meaning Neal and Del are anywhere between 50 to 500 miles from their destination.