The Ending Of Atonement Explained

The 2007 film "Atonement", which was adapted from a 2001 novel by the famous English author Ian McEwan, went on to garner a number of Oscar nominations in the year of its release. This included best picture and best writing of an adapted screenplay, as well as best original score, which it ultimately won (via IMDb).

The film features a cast that includes James McAvoy, Saoirse Ronan, Keira Knightley, Benedict Cumberbatch, and Juno Temple, the latter of whom many would recognize from the Apple TV+ series "Ted Lasso." It was director Joe Wright's second time working with Knightley, after the 2005 adaptation of the classic Jane Austen novel "Pride & Prejudice."

"Atonement" begins in 1930s England before moving on to World War II. The film tells a complicated narrative that spans a number of years and is split into three distinct sections, each one focusing on a different period in the life of Briony Tallis. Most of the film is presented as a re-telling of key events in Briony's life during these time periods; however, the movie's ending focuses on an elderly Briony (Vanessa Redgrave) who reveals that the film's middle section was largely invented by her and that the real-life fate of certain characters was grimmer than what the audience had been led to believe. Many viewers were left curious as to what the film's tragically sad ending truly meant, and what it indicated about the characters.

Here is an explanation of the ending of "Atonement."

The meaning of the film's title

Content warning: The following article contains discussions of sexual assault. If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

In the third section of "Atonement," the audience meets an elderly Briony, played by Vanessa Redgrave, as she's giving an interview on television about a book she wrote called "Atonement," which is described as an autobiographical novel. In the process of being questioned about this, Briony reveals that Robbie Turner (James McAvoy) and Cecilia Tallis (Keira Knightley) never got back together again after the night when Briony accused Robbie of raping Lola Quincey (Juno Temple).

This, in turn, establishes that the middle section, in which Briony visits Cecilia and Robbie, was fictional in the context of the film. The second section depicted that Robbie and Cecilia were now living together when Briony tracked her sister down to ask for her forgiveness for Briony's accusation, which led to Robbie's incarceration. Briony reveals that the truth is that Robbie died at the beaches of Dunkirk while waiting to be evacuated, and Cecilia died a few months later during a bombing raid on London.

This indicates that any semblance of a happy ending for Robbie and Cecilia that the audience has seen up to that point has been a figment of Briony's imagination, a way for her to rewrite their love story after having been the cause of their separation years ago — the titular atonement. It also explains two more important facets of the story: why it showed Robbie's time at Dunkirk, and why Briony is the character on whom the story has focused all this time. In the case of Dunkirk, the audience was, in fact, watching Robbie's last day and imminent death. In the case of Briony, the story is a bit more complicated.

Briony has come to see the true meaning of love

Sensitivity note: This section touches on sexual assault and rape.

The first third of "Atonement," in which Briony is played by Saoirse Ronan, shows that the character conflates sex and violence, and does not believe in love. When she walks in on Robbie and Cecilia making love in the library, her first thought is that her sister is being attacked. Her first comments afterward are about the marks Lola has on her arms. Briony also looks at the lewd love letter Robbie sent Cecilia as an indicator of the violence she later thinks she sees him inflict on her sister.

In the process of conflating sex with unpleasantness and violence, she concocts her own version of the relationship between Cecilia and Robbie, one where love is absent. This is further driven home by her play, which is about the foolishness of love, and even describes the prince in the story as remorselessly wicked. When she comes upon Lola after her attack, it's Briony who convinces Lola that Robbie attacked her, not Lola who convinces Briony. And it is this version of the story that everyone believes, despite it being fiction rather than fact.

In the film's final third, it's apparent that the story is another example of Briony's tendency to replace the truth of the situation with her own fictional version. However, in writing Cecilia and Robbie a happy ending, it's clear that she's come to understand the difference between love and sexual assault, and is trying to repair what she broke.

Class and its role in the story

Sensitivity note: this section touches on sexual assault and rape

Prior to Briony accusing Robbie, we see that he is reliant on the generosity of the Tallis family. This puts him in a certain light to the rest of the family and leaves him unable to defend his innocence. It's clear that Briony doesn't understand this intersection of class in the first third of the movie, as she's unable to understand how going to jail will fundamentally alter Robbie's life. In the process, she indirectly causes his death, as he gets drafted into the army as a consequence of being in jail.

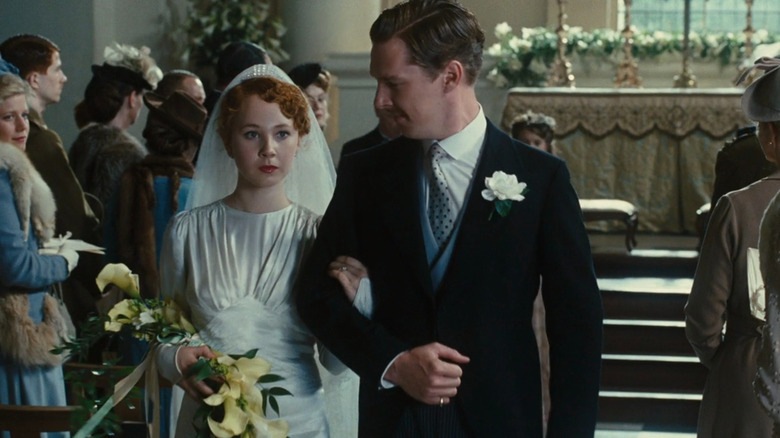

Paul Marshall (Benedict Cumberbatch), on the other hand, is seen as a trustworthy figure primarily because of his wealth, which insulates him from any possible accusations of sexually assaulting Lola. While it's unclear whether the marriage Briony witnesses between Lola and Paul is real or another concoction on her part, it is clear that she recognizes that not only was Paul the real perpetrator of the crime but that her actions may have led to Lola being silenced.

Briony's insistence on being a nurse during wartime suggests that she, like Cecilia, comes to understand the part her class privilege played in dooming Robbie. Furthermore, it's apparent that Cecilia understands this from the start, and Briony's portrayal of Cecilia at the end shows that Briony realized Cecilia came to that understanding before Briony did. This aspect makes the movie one of the better stories about redemption as well.

The class dynamics are evident in the source material as well

This exploration of class issues and how they affect the characters' trajectory is something Joe Wright and writer Christopher Hampton picked up from the original novel by Ian McEwan. The essay "The Roles Of Social Class In Atonement By Ian Mcewan" highlights this, pointing out how Paul and Robbie's lives are both affected by the rape of Lola, but it's not the action that defines it, but their social classes. Robbie effectively is punished not for the crime, but for the perceived sin of being a member of the lower class.

"Robbie Turner is a character that McEwan uses to exemplify the advantages and disadvantages of being an educated member of the lower class. Although Robbie is merely the gardener of the Tallis household, he is provided the liberty of being an equal member of the family. His education is what makes him preferable when being compared to the cooks and maids," the essay notes. Robbie was only able to get an education thanks to the generosity of the Tallis family patriarch, as Cecilia points out. "Marshal goes on to marry Lola, representing that he had lost nothing from the event. Robbie dies as a grunt in the war; righting wrongs that he had never committed," the essay adds.

In the book "Evading Class in Contemporary British Literature," author L. Driscoll draws a parallel between Briony's awareness of class at the end of the book and McEwan's own class consciousness. "It is clear that 'Atonement,' by silencing and killing off the working-class Robbie Turner suffers its own textual guilt," Driscoll explains, adding that whatever sympathy people feel for Briony after her actions indirectly lead to Robbie's death is, without them knowing it, redirected toward the novel's author. "We forgive her, we forgive him, we forgive ourselves," Driscoll continues.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).