The Untold Truth Of Apocalypse Now

"My film is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam." This is how Francis Ford Coppola described his masterpiece, Apocalypse Now, to the press covering the 1979 Cannes Film Festival, where the film made its debut. It may seem like a grandiose statement, but the war in Vietnam was a conflict that dragged on longer than anyone expected, saw insane amounts of drug abuse and brutality, and forced everyone involved to examine their very souls in ways that none before it had. The same things can be said of Coppola's film.

Let's examine some of the lesser-known details behind the greatest war movie ever made, one that nearly destroyed the man who created it and many of those around him, a stunning artistic examination of one of the greatest wounds to ever be inflicted on the American psyche—Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now.

George Lucas was the original director

Coppola co-founded his studio American Zoetrope in 1969, along with another young filmmaker by the name of George Lucas. Their plan was to use the studio to gain financing outside the established Hollywood system, enabling them to make the kind of films they couldn't otherwise—and Apocalypse Now was to be the launchpad for their operation.

The screenplay by veteran scribe John Milius was an updated retelling of the 1899 Joseph Conrad novel Heart of Darkness, with the setting changed to Vietnam, where war was currently raging. Coppola intended for Lucas to direct the picture, but as the war became increasingly controversial among the public, they found themselves unable to secure financing. The film was put on hold, and Coppola accepted a job from Paramount Pictures, directing one of his most successful films—The Godfather—largely to keep his own studio from going broke.

The Godfather's Oscar-winning success—along with that of its sequel and 1974's The Conversation, which was nominated for Best Picture and for Coppola's original screenplay—kept American Zoetrope afloat, and by 1976 Apocalypse Now was finally ready to be put into production. By that time, however, Lucas had become sidetracked with a little project called Star Wars, a movie which Coppola has mixed feelings about to this day. Speaking with Screen Daily, he said, "I think Star Wars, it's a pity, because George Lucas was a very experimental crazy guy and he got lost in this big production and never got out of it."

Harvey Keitel was the original lead

The war had ended by this time, and the story was tweaked to move away from a "documentary" feel and more towards a meditation on the brutality and senselessness of battle. Coppola offered the directing job to Milius before finally agreeing to take on the film himself, and he decided it would be shot on location in the Philippines. The budget was set at $12 million, and the shoot was planned to take six weeks—but signs of trouble appeared early, as Coppola initially had trouble filling out the cast.

In a very small nutshell, the film tells the story of Captain Benjamin Willard, assigned to find and terminate "with extreme prejudice" the insane Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, who has been carrying out unauthorized operations and has set himself up as a godlike ruler within neutral Cambodia. Coppola's first choice to play Kurtz, Orson Welles, turned down the role, and his second—Marlon Brando—couldn't make up his mind. Al Pacino, Jack Nicholson, and Robert Redford were all considered before Brando finally agreed to join the cast.

Likewise, the lead role of Capt. Willard was turned down by Pacino and Steve McQueen before Harvey Keitel was finally cast. But this turned out to be temporary—two weeks into the shoot, Keitel's performance was deemed too intense for the character, and he was replaced with Martin Sheen. Unfortunately, it was pretty much the worst possible atmosphere for Sheen to step into at that time.

Drugs were plentiful

Sheen arrived on set in the grip of a severe drinking problem, and in a fragile state of mind which Coppola was all too willing to exploit. For one scene, Sheen was kept drunk for two days while the cameras rolled, with Coppola subjecting him to what can only be described as psychological abuse. One cast member remembered, "Francis had this way of directing... he would tell Martin, 'You're evil. I want all the evil, the violence, the hatred in you to come out'... [Coppola] did a dangerous and terrible thing. He assumed the role of a psychiatrist and did a kind of brainwashing on a man who was much too sensitive. He put Martin in a place and didn't bring him back."

His lead may have been in an alcoholic daze, but he wasn't the only one—Coppola and many members of the cast and crew were either drunk or on drugs during the shoot. Actor Sam Bottoms plowed through LSD and marijuana as if supplies were limited (they weren't), and the legendary Dennis Hopper kept up a regimen of drugs and alcohol that would kill a horse: a case of beer, a half gallon of liquor, and three ounces of cocaine. Parties raged long into the night when cameras weren't rolling, and it started to become obvious that the shoot would take a little longer than expected—and then the real trouble started.

The production suffered ridiculous setbacks

As Sheen was beginning to fall apart psychologically, a break in filming came along—but not a fortuitous one. A typhoon blasted through the area where filming was taking place, destroying several expensive sets and forcing cast and crew to fly back to the United States. Sheen, for his part, was highly reluctant to return. According to a friend, "When Marty came home after the typhoon he was real scared. He said, 'I don't know if I am going to live through this. Those f***ers are crazy'... It was freaky; at the airport he kept saying goodbye to everyone." But he was convinced to return, and upon doing so promptly had a heart attack and a nervous breakdown.

There were other difficulties as well. Unable to secure the support of the Pentagon, Coppola had turned to Philippines president Ferdinand Marcos to supply helicopters and other military equipment—which Marcos was prone to taking back when said equipment was needed for actual military operations. This would cause more delays in filming, as would the tropical diseases which ran rampant on set and could sideline cast and crew members for weeks. Adding to all the stress for Coppola was the fact that the production was absorbing virtually every dollar he had, threatening to bankrupt not only American Zoetrope but Coppola personally if the finished product wasn't successful.

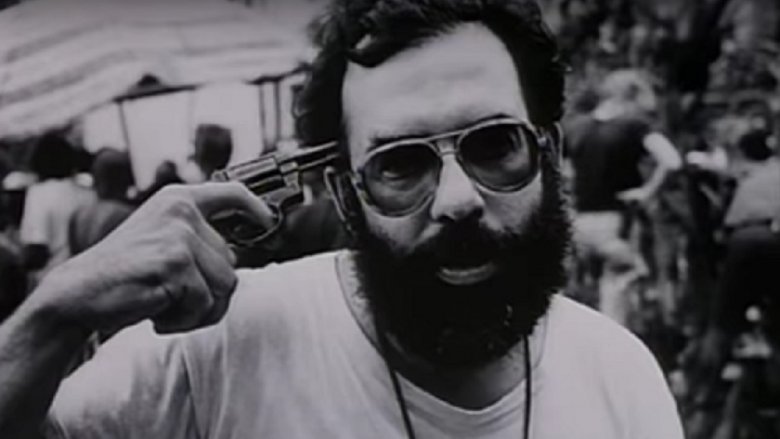

Coppola threatened to kill himself (three times)

As the production ballooned out of control, Coppola was forced to take drastic measures just to keep cameras rolling. The initial budget was obliterated less than three months into the shoot, which was also weeks behind schedule. Coppola remedied the situation by signing over his house and winery to the bank, pumping a whopping $30 million—over $120 million in today's money—of his own personal funds into the production. After Sheen's heart attack, Coppola blamed himself, having a nervous breakdown of his own along with an epileptic seizure.

So heavily did the production weigh on Coppola that on no less than three separate occasions, he announced his intention to kill himself. He would later reflect on the experience on behalf of himself and the entire cast and crew, saying, "We were in the jungle, there were too many of us, we had access to too much money, too much equipment—and little by little we went insane." Hopper agreed, telling the press, "Ask anybody who was out there, we all felt like we fought the war."

Marlon Brando was an absolute nightmare

Col. Kurtz only appears near the end of the film, but when Brando arrived on set to shoot his scenes, it quickly became obvious that there would be trouble. For starters, he was bald, overweight, and hadn't read the screenplay or the source novel. He also smelled from lack of bathing, was perpetually drunk and high on cocaine, and he refused to be on set at the same time as Dennis Hopper, whom he couldn't stand.

Coppola sent his already-fried brain into overdrive figuring out how to accommodate the legendary actor. His initial thought of depicting Kurtz as having grown fat in his life as a god to the natives, surrounded by food, booze and women, didn't go over well with the vain Brando, who had been a sex symbol in the not-too-distant past. He settled on a mysterious presence for the character, a hulking, vague figure always shot in shadow—but then there was the issue of dialogue. Brando simply could not remember his lines as written in the script, so Coppola would record the actor improvising for days at a time, typing up pages upon pages of these improvisations mixed with actual dialogue and recording the result. This was piped in via an earpiece to Brando, who would recite what he was hearing. Somehow, this convoluted technique resulted in a positively immortal performance, although Coppola would later go on to describe Brando as "like a kid, very irresponsible."

Real dead bodies almost made it into the film

Perhaps more than any other film, Apocalypse Now accurately depicts the horrors of war and its dreamlike, often hallucinatory feel. The scene in which Willard and his crew arrive at the mad Colonel's compound—and skinned, dead bodies can be seen hanging from the trees in the background—illustrates this vividly, and the story behind the scene illustrates just how chaotic the production was.

According to co-producer Gray Frederickson, production designer Dean Tavoularis wanted to make the shot a little more authentic than was ethically possible. While Frederickson was chewing out Tavoularis over a rat infestation on one set (which Tavoularis said was "intentional—it gives it real atmosphere") a nearby prop man blurted out, "wait 'til he hears about the dead bodies." An infuriated Frederickson was led to a pile of actual cadavers Tavoularis intended to use in the scene. He'd secured them from a local who was in the business of supplying cadavers to medical schools—and who, as it turned out, was a grave robber. "The police showed up on our set and took all of our passports," Frederickson said. "They didn't know we hadn't killed these people because the bodies were unidentified. I was pretty damn worried for a few days. But they got to the truth and put the guy in jail." Later, soldiers came to take the bodies away—but since nobody was paying for a burial, they promised simply to "dump them somewhere."

The film took ten years to produce

When all was said and done, it took a decade from the time Lucas and Coppola first laid eyes on Milius' screenplay in 1969 until the film's eventual release. The planned 12-week shoot snowballed into a staggering 68 weeks; the $12 million budget nearly tripled, and even after the shoot wrapped, the film would spend another two years being edited.

Some details of the troubled production had made their way to the public, and since the film had been shot outside the Hollywood system halfway around the world in a time before the internet, it acquired legendary status long before it was even screened. But that status increased further when Apocalypse Now was shown for the first time at Cannes—where critics and audiences were blown away by a film that, technically, wasn't even finished.

An unfinished version tied for the Palme D'Or at Cannes

Coppola's remarks to the press at Cannes weren't so much the words of an egotistical artist as they were a startlingly accurate description of what he knew he'd put to film: an actual journey into the heart of darkness, an experience he and his cast and crew put themselves through which so closely mirrored the American experience of Vietnam as to be perhaps its only possible definitive statement. Perhaps it's for this reason that he was confident enough to enter the film into competition as a work in progress, before the final edit was complete—and it's certainly the reason why his rough cut tied for the Palme D'Or, the most prestigious prize of the most prestigious film festival in the world.

The film would go on to gross over $78 million (over $260 million today) and be nominated for a slew of Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Robert Duvall—Sheen was not nominated for his performance). It won only two—for Best Cinematography and Best Sound, fitting because it's among the most visually striking films of any era, and it revolutionized the way movies sound.

It gave birth to 5.1 surround sound

Coppola wanted the picture's sound design to match the scope of his vision, and sound designer Walter Murch was tasked with making it happen. Conventional sound in features of the time consisted of three audio tracks—left, right and center—behind the screen, with a single mono "surround" track behind the audience. One of the first films to offer an improvement on this experience happened to be Star Wars, which featured two supplemental subwoofer tracks that vastly increased the overall bass response. Coppola and Murch also wanted to use six tracks, but they had something different in mind—for the first time ever, they wanted to augment the audio with two stereo surround tracks, in an attempt to more accurately capture the sounds of helicopters.

They accomplished this with the final audio mix, which featured the standard main channels (left, right and center), two surround tracks, and one supplemental subwoofer track—which you may recognize as an accurate description of 5.1 surround sound. According to Murch, Coppola had toyed with the idea of building a theater in the middle of the United States that could support the format, a tourist attraction where Apocalypse Now could run for ten years or more. That, of course, never materialized—but it worked out in the end, as 5.1 surround would go on to become a standard audio configuration in both cinemas and home theaters around the world.