The Black Phone Review: Don't Pick It Up

- Creepy, revenge-fueled concept is a good hook

- No backstory for the film's outlandish flourishes

- Mediocre acting

- Too many stretches of disbelief

Masked killers are creepy. Child abductors in vans are terrifying. Psychic kids and supernatural ghost stories can scare you so badly that you'll need to sleep with the lights on. What if a film was made that contained all of these elements, yet made no attempt to explain any of them? It would be scary, it wouldn't make much sense, and it would be called "The Black Phone."

Director Scott Derrickson ("The Exorcism of Emily Rose," the "Sinister" films) returns to his horror roots with a bit of newfound "Doctor Strange" flair in his toolbox. But despite some inspired shots, and a few jump scares that will have you tossing your popcorn into the air, lackluster teen acting and silly lapses in plausibility undermine an otherwise intriguing idea. This is one incoming call that simply can't find a connection.

The film begins with a "Dazed and Confused" vibe, as kids in a Denver suburb go about their business in 1978. There is baseball to be played, bikes to be ridden, science partners to be selected — interrupted occasionally by playground brawls and boys' room confrontations. At the center of all these goings-on are Finney (Mason Thames) and his sister Gwen (Madeleine McGraw), who live in fear of their hard-drinking, belt-wielding father (Jeremy Davies, giving the best performance of the film).

Boy after boy in Finney's periphery disappears, seemingly abducted by a man the local kids call "The Grabber." Soon the police are on high alert, and one of their few, desperate leads come in the form of Gwen's clairvoyant dreams, which may or may not be the key to finally stopping the abductor. But things get even more complicated one day when Finney finds himself talking to an amateur magician (Ethan Hawke) behind a creepy black van, who subsequently takes him prisoner.

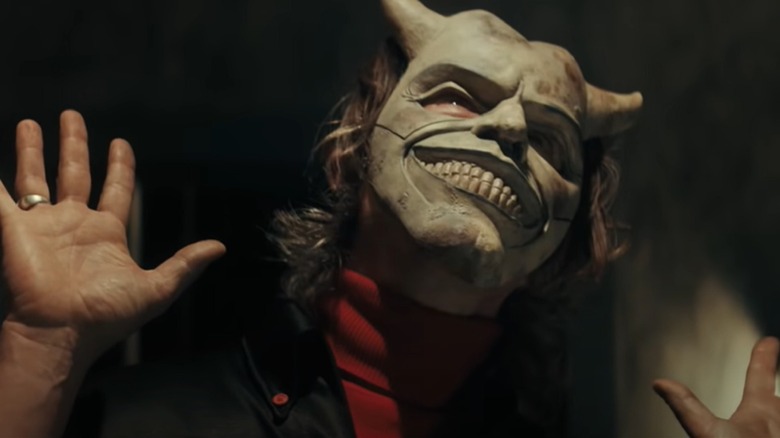

Finney wakes up alone in a room that makes "Hostel" look like the Mandarin Oriental, surrounded by little more than an old mattress, a toilet, and some rolled-up carpeting. Oh, and there's also a disconnected phone on the wall ... a black phone. His abductor, clad in a creepy two-part mask with a menacing smile and devil horns, tells him that the rotary phone doesn't work. But when Finney is alone, the phone rings, and on the other end is a series of static-filled transmissions that appear to be from the serial killer's former victims. They give Finney advice on how to stay alive, while his sister frantically attempts to dream up his whereabouts.

The devil inside

If all this sounds a little kooky, that's because it is. "The Black Phone" feels like an attempt to cram several different films into one, and while genre-blending can be a good thing, it isn't when the film doesn't take the time to do any of them well.

Take the mask, which is a well-designed one that might even inspire a few Halloween costumes this year. Hawke's Grabber sometimes wears the mouthpiece, sometimes wears the whole thing, then seems positively powerless when it is ripped from his face — but we're never told why. Couple this with what might be the laziest abductor ever depicted in a movie (the kid removes bars from a window and he never notices, clangs noisily and he never checks up on his prey, discovers him asleep after he purposefully leaves the door unlocked, and kidnaps all his victims from what feels like a 3-block radius), and it's extremely hard for a viewer to put themselves in the "What if this happened to me?" mindset, which is what such films are supposed to do. How can we be afraid of such a poorly defined, incompetent big bad driving a van that might as well read "I'm here to abduct neighborhood children" on its side?

Then there are the supernatural elements of the film. There are a few brief references to Gwen's deceased mother, who apparently also had clairvoyant powers that her father seems to blame for her undoing. But little is ever offered beyond that as a reason why she has these powers, and nothing is offered to explain why Finney also seems to have his own power to speak with the dead, via this disconnected telephone.

Time to phone a friend

Taken alone, any of these plot shortcomings might be worthy of forgiveness. Added up, it's death by a thousand cuts, and the most stinging slash of all hasn't even been mentioned yet. When the police (E. Roger Mitchell and Troy Rudeseal) are searching for whatever neighborhood house these kids are all disappearing into, they are greeted at one stop by a hyperactive, dim-witted amateur detective named Max (James Ransome) who talks their ears off with cocaine-fueled conspiracy theories. We soon learn that Max is the brother of the Grabber, and although he is obsessed with the abductions, he doesn't realize they're happening right under his nose.

Drug-addled dimness aside, it is mind-boggling to try and comprehend how this man could not know that his brother is the killer. The film offers us no scenes of Hawke's character trying to hide his hobby, no indication of what their brotherly dynamic is like — nothing that could help sell this notion that the Grabber is slick enough to pull any of this off. The man makes a point of leaving behind black balloons every time he kidnaps someone and doesn't bother to take away the sharp flashlight/pen that Finney uses to cut his forearm during the abduction. This is no master criminal.

It's all a shame because the film does have flashes of potential and moments where it feels like it could transcend a simple slasher movie. It's certainly more ambitious than most films of its genre, as evidenced by both its visuals — Gwen's dreams and the manifestations of the "dead" boys standing around Finney, creepily mouthing along to their phone calls, are striking — and its central gimmick of largely-anonymous victims (one is simply called "the paperboy") striking back from beyond the grave.

But the film isn't helped by its acting. Ethan Hawke does a fine job, even if you can't see his face for the majority of his scenes; and Jeremy Davies is hard to look away from, as always. But everyone else is serviceable at best, distracting at worst. In the end, "The Black Phone" is a forgettable trifle, a half-baked idea as unsatisfying as a dropped call.