The Ending Of Elvis Explained

The story of Elvis Presley, the King of Rock and Roll, was the stuff of Hollywood legend even while was still alive. A 19-year-old truck driver for Memphis, Tennessee, takes the world by storm with an incendiary blend of Country music, Gospel, and Rhythm and Blues. After conquering the charts he conquers Hollywood, starring in over 30 films made in just over a decade. And just when it seems that he's washed up and forgotten, he releases a television comeback special in 1968 that rockets him back to glory.

Many films made about Presley's life, from John Carpenter's 1979 television movie starring Kurt Russell to the 2005 CBS miniseries, end conveniently at this moment of triumph, eliding or outright ignoring the last decade of his life — the years when artistic stagnation and debilitating substance abuse issues turned The King into a clown. 2022's "Elvis," the long-awaited biopic from visionary director Baz Luhrmann, is different. For one thing, no other film about Presley has had Luhrmann's lurid, maximalist style, a wild kaleidoscope of light and sound designed to evoke the kind of sensory overload Elvis' teenage fans must have felt when hearing his music for the first time. But just as importantly, Luhrmann and his screenwriters Sam Bromell and Craig Pearce don't ignore the superstar's sad final years, locked away in a gilded Las Vegas cage by his manipulative manager, Colonel Tom Parker.

For many Elvis fans, it's an era that they would like to pretend never happened, as anyone old enough to remember the Old Elvis vs. Young Elvis postage stamp controversy can attest. But for Luhrmann, the era is neither a postscript nor an inconvenient truth, but essential to the film's unique point of view. Let's take a look at the ending of "Elvis." Naturally, spoilers ahead.

The Showman and the Snowman

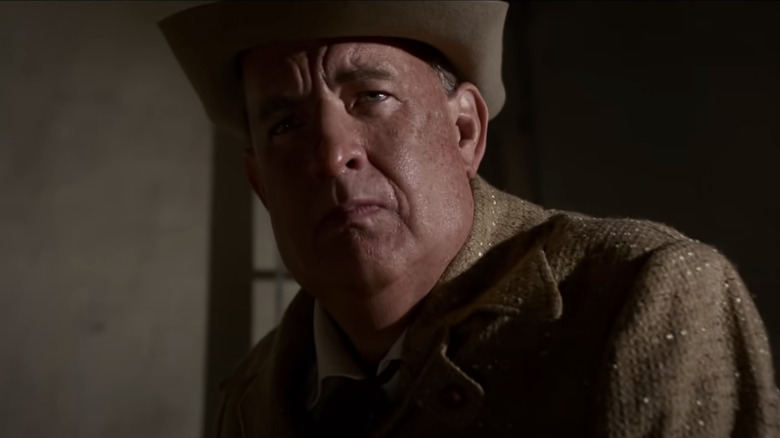

Luhrmann's excessive, often anachronistic visual panache always gets a lot of attention, whether he's depicting 1890s Paris or 1920s New York. "Elvis" is no exception, with its whirling roulette wheel camerawork and hip hop remixes of Presley songs. But the film's most daring conceit is arguably the way it tells the story of Elvis from the vantage point of Colonel Tom Parker, played by Tom Hanks under a mountain of prosthetics and a thick Dutch accent. Parker looks back on his life with The King as he lies dying in a Vegas hospital bed in 1997, wandering through a spectral casino as the memories come flooding back.

Over the years since Presley's death, Parker has widely come to be seen as a villain, manipulating his one and only client's trust and taking far more than his share of the profits (per Smithsonian). Luhrmann's film doesn't disagree with this version of the facts, but in Parker's mind he is Elvis' other half, the carnival barker (or "snowman") to his sideshow freak (or "showman"). The film's most compelling tension is between the blameless, almost victimized way Parker sees his own relationship with Elvis compared with what we the audience see happening on screen. This tension is exposed early in the film with a brief flash to 1974, when Elvis collapses backstage before a concert and Parker makes it perfectly clear that the only thing that matters is that he gets back on his feet and performs.

Firing the Colonel

As the film enters its final act, we revisit that moment in 1974 when Presley collapses with added context. At this point, Elvis has been performing at the International Hotel in Las Vegas for years due to the fact that Parker signed him into essentially a lifetime contract in exchange for the forgiveness of Parker's massive gambling debts. Parker has also been promising Presley his first global tour for years, going back to the 1968 comeback special, only to delay the start of the tour for one reason or another. The truth, however, finally comes to light just moments before The King collapses: Parker keeps delaying the tour because he came to the United States illegally and doesn't have a passport. His name is not even Tom Parker, nor was he ever a colonel.

After he collapses, Presley is given a shot of amphetamines to get him up and going again for the show. He takes to the stage, inebriated and incensed by his manager's betrayal, and in spectacularly dramatic fashion, fires Parker in the middle of his performance. It's a deeply satisfying moment in the film, even if it is nothing more than a fantasy. According to Elvis biographer Alanna Nash (via USA Today), Presley and Parker's professional falling out occurred after a show, not in the midst of one, and for a completely different reason. Furthermore, Parker's immigrant status wouldn't come to light until after Presley's death; there is no evidence that The King ever suspected that Parker was anyone other than the West Virginia native he claimed to be.

Bills, Bills, Bills

Parker's countermove, however, is accurate to real life. After being fired by Presley, Parker retires to his office and drafts an invoice for unpaid promotional work dating back to 1955, totaling over $8 million. According to Nash, this is based on a real incident, though the exact dollar amount of the invoice is unknown. Elvis' father Vernon ("Moulin Rouge" bad guy Richard Roxburgh) breaks the news to his son that Parker's bill would bankrupt them. Elvis, furious, storms out of his suite, only to find Parker waiting for him outside.

The two men argue viciously. Elvis gnashes teeth and threatens to kill Parker; the Colonel in turn belittles Presley's career, reminding him (unfairly but honestly) that the comeback special audience that loved him so much was a plant, prompted to cheer by a flashing "applause" sign. The scene is in many ways the climax of the film, and Butler and Hanks give it their all. Hanks delivers the film's mission statement in this scene, declaring, "We're the same ... two odd lonely children, reaching for eternity." His entreaty falls on deaf ears as Elvis walks out of the Colonel's life forever.

Are You Lonesome Tonight?

Forever, though, is never quite as long as it seems. Luhrmann films the aftermath of Elvis and Parker's falling out from outside the International Hotel, reminding us how intertwined these men are. Through the windows we see Parker's office on nearly the top floor of the hotel; the camera travels up and there is Elvis' penthouse suite, just one floor above. Parker's ceiling is Presley's floor; even if they wanted to be rid of each other, they never could be.

Elvis, meanwhile, sits at his piano and plays a minor-key version of his 1960 ballad "Are You Lonesome Tonight?" Having Elvis play sad covers of his own hits when pouting is a stylistic device the film breaks out several times in the course of the film, and it never stops being just a little goofy. Finally, a defeated King collapses on his sofa in front of his three television sets. Vernon comes in to check on him, Elvis asks his father to ask Parker to fetch his physician for something to help him sleep. Like the prescription drug addiction that consumed the final years of Presley's life, Colonel Tom Parker cannot be quit so easily.

One Year Later

The film fades to black with a title card: "One Year Later." Suddenly it's 1975 and Elvis' career has transformed into something different. Presley is now a media curiosity, a real-life version of the sideshow act Parker always considered him to be. He's gained weight, he's separated from his wife Priscilla (Olivia DeJonghe) and rarely sees his daughter Lisa Marie, and when he's not performing in Las Vegas he's holed up like a hermit in his Memphis mansion Graceland. There is one glimmer of hope, as talks are apparently ongoing to have him star with Barbra Streisand in a remake of "A Star is Born," but we in the audience know that will sadly never come to be; Streisand will star with folk singer/songwriter Kris Kristofferson instead.

Outside of his private jet, named after his daughter, Elvis and Priscilla have a tender conversation. Like most pieces of dialogue in the film, its primary focus is to establish for us the state of Elvis' life and career in this moment, and what his dreams and goals are. Elvis still wants to make one good movie, after dozens of cheap musicals, and worries that nothing he's ever done will amount to anything when he dies. The film presents this as Elvis' final conversation with his ex-wife, even though he would live for another two years, which the film glides over completely en route to The King's death.

The King is Dead

From that scene on the tarmac, the film skips ahead two years to the announcement that Presley has been found dead in Graceland at age 42. Rather than try to recreate the spectacle of Elvis' funeral procession or the massive outpouring of public grief that followed, Luhrmann opts instead to use archival footage of the real thing. He also includes an audio excerpt from President Jimmy Carter's statement on Presley's death, in which he said, "His following was immense, and he was a symbol to people the world over for the vitality, rebelliousness, and good humor of his country." Not too shabby for a kid who scandalized the nation just two decades earlier.

In choosing not to recreate Elvis' funeral, the film also skips over the fact that Parker reportedly wore a Hawaiian shirt and baseball cap to the service and tried to strike deals with mourners, according to biographer James Dickerson (via The New York Post). We'll never know whether his behavior came out of callousness, sociopathy, denial, or some misguided sense of showmanship, just to keep everyone talking about him. His casual dress and apparent lack of emotion has also been cited as evidence in the long-standing conspiracy theory that Presley faked his death and is still alive (via E! News).

The Final Show

As the nation mourns the loss of The King, the film flashes back to Presley's final performance in Las Vegas. Luhrmann has thus far been reluctant to make Butler up as the so-called "fat Elvis," but here the young actor is decked out in wide pair of jowls and double chin, mumbling and stumbling as he sits down at the piano, with his microphone held by one of his musicians, and belts out an emotional rendition of the Righteous Brothers' "Unchained Melody."

Sweat pouring down his face, the camera keeps tight on Butler in an intimate, slightly gawky way. It's different from the way any of the film's musical numbers have been filmed, but soon we understand the reason why, as Luhrmann cuts from Butler as Elvis to footage of The King himself singing, accompanied by a short montage of the real-life Elvis in many of the situations we've seen dramatized in the film. It's a jarring transition, as we see just how accurately Luhrmann and Butler have recreated these moments in Presley's life. It's also a reminder of just how powerful Elvis' voice and presence were, even in his final days. He gives a showstopper performance at that piano, and the audience hangs on every note.

Who Killed Elvis?

In the end, Elvis cannot speak for himself, and so Parker does it for him, as he did for most of their life together. Who or what killed Elvis, Parker ponders as he shuffles about his purgatorial casino floor in a hospital gown and IV drip. It was not the pills and drugs, administered by doctors who should have known better and enabled by Parker, Vernon, and Presley's whole entourage (the so-called "Memphis Mafia") who were all complicit in working Elvis to death. And it wasn't Parker's greedy mismanagement of Elvis' business, which kept him performing at a miserable pace for years; Parker is all too quick to absolve himself of that guilt.

No, of course, it's we who are the ones who killed Elvis, with our incessant love for him and his inability to say no. Parker's monologue here is a fascinating moment in the film; Luhrmann and Hanks keep Parker at arm's length, unwilling to hold the audience's hand on how to feel about this duplicitous conman. Instead, they let Dutch carny and possible murderer Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk snow us to the very end. As Parker dies, a field of stars dims until there are just two left. One star fades slowly, while the other grows and shines like a rhinestone before snuffing out in a flash.

Epilogue

After the screen fades to black, we get a series of post-scripts filling us in on how the saga of Elvis and the Colonel played out in the years after Presley's death. The film plays loose with what Presley and the rest of the world knew about Parker's background; in real life, it wouldn't be until 1980 when anyone could confirm that he was of Dutch descent and entered the country illegally as a 30-year-old man (per Smithsonian). Eventually, though, Parker's financial malfeasance came to light, and after a series of lawsuits brought on by Elvis Presley Enterprises, a judge ruled in 1982 that Parker had no legal claim to any part of the Presley estate.

In his final two decades, Parker spent his days in Las Vegas, puttering around one casino floor or another, pouring his immense wealth down the drain. He made few public appearances or statements in those years, emerging from the shadows only on rare occasions such as the 1993 release of the Elvis postage stamp (via The Washington Post). Presley, meanwhile, far from the forgotten lounge singer he feared he'd become, remains an international superstar nearly 50 years after his death, and one of the highest-earning dead celebrities of all time, according to Newsweek. His life and work still inspire admiration and controversy. As any visitor to Memphis or Las Vegas can attest, Elvis remains hard at work, and in a way, so does Colonel Tom Parker.