The Ending Of The Exorcist Explained

Something is wrong with Regan MacNeil. Her mood has soured. She's cussing. She's speaking in tongues. Pre-teens, right? Only, this isn't teenage rebellion. And the doctor's aren't entirely sure that it's pathological. Maybe it's time to call a priest.

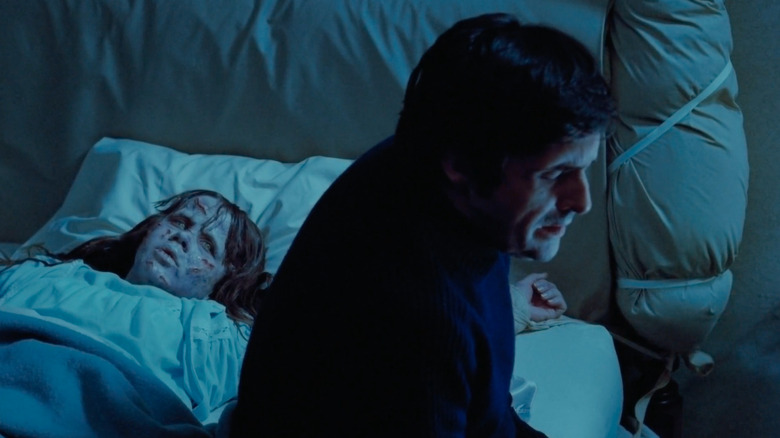

"The Exorcist" follows the case of little Regan (Linda Blair) and all the strife, tears, and religious epiphanies that spring up in the wake of her wagging tongue, rattling bed frame, and projectile vomit. Her mother, Chris (Ellen Burstyn), is an actress, recently divorced, and trying to do her best to raise her daughter. Desperate for something, anything, that can cure her child, Chris turns to a local Jesuit priest named Father Karras (Jason Miller), a man wrestling with demons of his own. So it all comes to this — an excellent day for an exorcism. Teaming up with the elder statesman Father Merrin (Max von Sydow), Karras ventures forth into the icy bedroom to save the life and soul of an innocent girl.

As the final beats of "The Exorcist" play out, the demon inside Regan puts on one hell of a show (pun intended). Through all the fluids and obscenities, Karras and Merrin prove victorious ... but lose their lives in the process, with Karras accepting the demon into his own body and sacrificing his own life to save Regan's.

A critical and financial smash hit that endures to this day under the superlative of "the scariest film ever made," audiences are sure to return to William Friedkin's 1973 classic for generations to come. So, all that said, let's look at the film's final moments to unpack the thematic threads, key plot details, and narrative punctuation marks that define the ending of "The Exorcist."

Be warned that this article contains major spoilers for both William Friedkin's 1973 film "The Exorcist" and William Peter Blatty's 1971 novel of the same name.

Both Father Karras and the MacNeils find their faith

Father Karras' faltering faith is a thread well-worth pulling on when you're trying to piece together what's going on in the ending of "The Exorcist." Somber, dark, and melancholic, when we first meet Karras, it's clear that he is a haunted man — head swirling with doubts that the demon inside Regan is keen to exploit. Any pre-existing existential uncertainty is made far worse by the intense guilt Karras feels for the recent death of his mother, who passed away alone in institutional care. "There isn't a day in my life when I haven't felt like a fraud," we hear Karras confessing to a fellow priest. Later, Karras says the quiet part out loud in a conversation with the president of the University of Georgetown: "I think I've lost my faith." Naturally, the demon immediately recognizes Karras as an easy mark — there's an open wound to prod, poke, and goad with impunity.

But at his lowest point, beaten down and bullied, Karras proves to himself, us, and the demon that his faith is strong. In an ultimate testament to his calling, Karras sacrifices himself to save Regan. It is a selfless act, done in earnest, by a man who truly believes in what he is doing. Like Chris MacNeil, who went from scoffing at New Age rumblings to pleading for an exorcist, Karras' skepticism galvanizes into belief when he's pushed up against a wall. "The attack is psychological, Damien," Father Merrin advises. "The point is to make us despair ... to reject the possibility that God could love us." And yet, when he does despair, Karras chooses love — to commit and stay by Regan's side, no matter what. After all, as the argument goes, if you think God's dead because of all the evil in the world, then how do you account for all the good?

Karras' sacrifice has similarities with a biblical exorcism

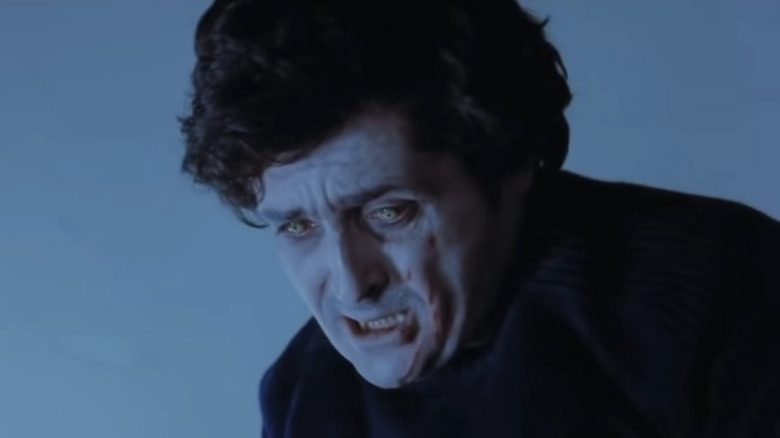

Shaken by the demon's mimicry of his dead mother, the grieving Father Karras is advised to leave Regan's bedroom at the behest of Father Merrin. When the young priest returns with renewed conviction to save the innocent girl's life, he is distraught to discover Merrin's dead body. Furiously, Karras begins beating Regan and demands that the demon possess him instead. As the demon passes into Karras' body, the priest's features contort, his eyes shift, and his hands shakily return to Regan's throat to finish the job. Then, as William Peter Blatty's screenplay describes, "Karras fights the force for control of his body ... compelling it toward the window." Launching himself through the pane of glass, Karras falls down the concrete steps outside, crumbling at the bottom into a lifeless bloody heap.

Karras' final sacrifice is one of the most iconic moments in a film full of iconic moments. And if you're familiar with your Bible, you'll know that this deadly approach to exorcism has a precedent. Mark 5:1-20 describes an incident where Jesus cured a possessed man by transferring a demonic entity into a herd of pigs that proceeded to rush off a steep cliff and drown in the lake below. To underline the reference, the demon in "The Exorcist" refers to Regan as a pig ("The sow is mine!"), and protest graffiti reading "fight pigs" (a pejorative for the police) can be seen on the flanking wall of the infamous staircase. In another fun twist, the demonic force in Mark 5:1-20 identifies itself as "Legion ... for we are many." Blatty's sequel to his best-selling novel would go by the same name and would be adapted for the screen seven years later as "The Exorcist III: Legion."

The MacNeil household now has a stable father figure (it's the Church)

Lurking, ever present, in the background of "The Exorcist" is the specter of divorce. Chris is a single mother, and neither she nor her daughter have truly recovered from the sting of the recent separation. There's a suggestion, intoned while Regan is being assessed by psychologists, that the 12-year-old's unsettling behavior might have something to do with her equally unsettled family life. Regan loved her father, Howard, dearly. Could this new entity, "Captain Howdy," be a harmful eruption of repressed pre-teen emotion?

And yet, as the Quillette remarks, despite being a tale about fatherlessness — both literal and spiritual — "The Exorcist" is jam-packed with father figures. While the metaphorical fatherly presence of Merrin and Karras is certainly important (and a stand-in for the paternal power of the Church), it's telling that the two men who do survive their run-in with the demon are biological fathers, namely lieutenant William Kinderman (Lee J. Cobb) and the housekeeper Karl Engstrom (Rudolf Schündler). As the Quillette article argues, "Exorcist" scribe William Peter Blatty "kills off the metaphor to show us the truth behind his fiction: the world needs more men like Kindrman and Engstrom — caring, loving men who remain present in their children's lives when they most need a father."

Blatty was himself a child from a fatherless home (his own dad, a cloth cutter, abandoned his family when Blatty was 8 years old). Blatty's socially conservative concerns about the crumbling traditional family unit are peppered throughout the 1971 novel and the film alike, both of which he wrote. How Blatty's own three divorces figure into his criticism, however, is something of a mystery. In any case, before the credits roll, we're treated to several images of Chris, Regan, and Father Dyer (William O'Malley) in the same frame. The nuclear unit is restored. The Church is Regan's daddy now.

The significance of Karras' medallion

Early in the film, we're tipped off that there's something special and especially meaningful about Father Karras' medallion. When Father Dyer visits Karras after the death of Karras' mother, the young priest has a nightmare in which his medallion free falls until it crashes to the ground. At the end of the film, when Karras offers himself up to the demon, Regan tears the medal from his neck before the evil presence transfers into Karras' body. There's an implication that the medallion was protecting Father Karras and that the demon would not or could not claim him as a host while the pendant hung around his neck.

As we see in various closeups, the medallion features an engraving of St. Joseph, Jesus' adoptive guardian. The patron saint of fathers, St. Joseph is a fitting saint for Father Karras, who becomes a metaphorical father figure for the MacNeil family in his sacrifice. Speaking of which, it's also worth noting that St. Joseph is the patron saint of persons living in exile, which certainly applies to Karras in a spiritual sense as he spends most of the film wrestling with his faith. St. Joseph is also the patron of holy death, which adds some ominous prescience to Karras' dream from earlier in the film.

At the end of "The Exorcist," Sharon (Kitty Winn), Regan's tutor, gives Father Karras' medallion to Chris. As she's driving away, Chris gifts Karras' St. Joseph medal to Father Dyer ("I thought you'd like to keep this"). In the 2000 director's cut, Dyer returns the medal to Chris, insisting she keep it for herself. Chris accepting a physical reminder of religious paternalism further hammers home the film's conservative thesis about the troublesome father-shaped gap in the MacNeils' household.

Faith triumphs where science fails

When Regan initially begins to exhibit signs that something is wrong, her mother does precisely what you'd expect from a 20th-century parent. She takes her child to the doctor. Scratch that – doctors. Hordes of them, each more perplexed and unsure of their diagnosis than the last. Is it mental illness? A pinched nerve? A tumor? A rare case of multiple personalities? It's anyone's guess. Secular knowledge is coming up short when it comes to the curious case of Regan MacNeil.

In an interesting twist, it's the flabbergasted doctors who point Chris in the direction of the Church. When Chris rejects the medical team's suggestion to put her daughter in an institution, the doctors sheepishly admit that there is one last resort. "Do you have any religious beliefs?" one doctor asks. "No," Chris responds, puzzled. "What about your daughter?" asks another. "No, why?" Chris responds. "Have you ever heard of exorcism?" asks the clinic director. "It's pretty much discarded these days, except by the Catholics who keep it in the closet." There's something mysteriously powerful about belief, the director confesses. If belief is there ... who knows what could happen.

While the rite ultimately claims the lives of two priests, Regan's exorcism proves a success. Faith then, the film argues, has the ability to answer questions science cannot. Catholicism is archaic, sure. But archaic problems require archaic solutions.

Regan remembers nothing ... or so it seems

Once the dust has settled and Regan is free from the demon, the MacNeil household prepares to pack up and move as far away as possible. Whether or not they got their damage deposit back is something of a mystery (can you get that much vomit out of a carpet?). In the film's final scene, Chris says her final goodbyes to Sharon and runs into the diminutive Father Dyer outside. "She doesn't remember a thing," Chris cautions, warning Dyer not to mention anything to Regan that could break the mental dam keeping the traumatic incident at bay.

And yet, the question of how much Regan remembers is ultimately kept ambiguous. Struck by Dyer's priestly collar, Regan leans forward and kisses Dyer on the cheek, and a wave of confusion passes over the young girl's face. Why did she feel compelled to do that? To express such love and gratitude to a stranger simply because they were a member of the priesthood?

Well, if you've seen "The Exorcist II" (in which case, our condolences), you'll know that Regan's run-in with the demonic Pazuzu is far from over. In the critically maligned sequel, we learn that deep down, subconsciously, Regan does remember the incident. (Not only that, but she's a member of a new phase in human evolution with special healing powers. Don't ask!). Arguably, it's a lot more interesting to leave Regan's memory of her possession up to the audience. That said, from Linda Blair's performance in the first film, it's clear that something deep in Regan's psyche has at the very least an impression of what happened, albeit hazy.

Blatty's goal was to emphasize the power of the Church

William Peter Blatty — the author of the novel "The Exorcist," as well as the writer and producer of William Friedkin's big-screen adaptation — was an emphatic Catholic. And as The Atlantic astutely notes, Blatty's novel fits in neatly with an era dominated by prominent thinkers and artists who were clearly influenced by Catholicism, including Marshall McLuhan, Jack Kerouac, and Anthony Burgess. As quoted in The Atlantic piece, Blatty considered his novel "an argument for God ... an apostolic work, to help people in their faith."

Indeed, "The Exorcist" is a kind of conversion story — a dramatization of the salvation that awaits on the other side of suffering, grief, and doubt. Father Karras, for his part, recovers his lapsed faith after grappling with his own pain and that of the MacNeils, who, for their part, find answers in the Church that science was unable to provide.

As noted by The Jesuit Review, the film (and the novel on which it's based) offer "a compelling illustration of spiritual warfare. It depicts Catholicism as a compass for truth, directing believers into God's armory, equipping them with spiritual weapons to combat arguments rather than inflict physical harm." By using the language of horror to communicate the stakes of Catholic belief to a larger audience, Blatty highlights religious rites, doctrines, and fears. "The Exorcist" (both the film and the novel) are still compelling if your spiritual allegiances lie elsewhere. But for Blatty, it's clear that the story of Regan's possession and Karras' lapsed faith are a distinctly Catholic story.

One of the horror genre's purposes is to scare you straight

It's fascinating how certain genre films have relatively conservative aims. American slashers in the mold of "Halloween" are a good example or horror's penchant for moralism. Promiscuous teens wind up dead, and only the unsullied virgins get to see the light of day. Plenty of horror films are built on the foundation of moral finger-wagging. And that admonishing tone makes a lot more sense when we consider horror's ancestor, the fairy tale.

Fairy tales are designed to teach children moral imperatives through grisly tales of man eating wolves, predatory witches, and all manner of ghouls that go bump in the night. Don't stray from the path. Don't go out alone after dark. Don't talk to strangers. You know the drill. Fairy tales (and some horror films) use our darkest fears to put unwieldy souls on the straight and narrow. And it's no coincidence that Catholicism uses a similar tactic, dangling the threat of eternal hellfire over the heads of prospective converts.

"The Exorcist" is an evocative example of how horror tropes can be weaponized to make socially conservative arguments. Arguments like "maybe if you had a husband and went to Church your daughter wouldn't have been possessed."

Despite its conservative message, The Exorcist received backlash from interest groups

"The Exorcist" is, ultimately, an argument for the power of faith and the Church. Regan's body and soul are saved not through science or psychology but because the MacNeil family appeals to priests who are willing to do anything to banish the evil that has commandeered her body. As religious news website Aleteia notes, "The Exorcist" is a film with a distinctly Catholic worldview. Not only does it argue that redemption can be achieved through suffering (or in Father Karras' case, the ultimate sacrifice of giving your life for someone else's), but "The Exorcist" also implores audiences to seriously consider the idea that demons are not metaphors but real physical threats that walk amongst us.

And yet, despite its unambiguously conservative message, "The Exorcist" received a deluge of pushback from special interest groups at the time of its release. As The New York Times noted with respect to the film causing undue panic in the general populace, "Theologians have warned that the film distorts church teachings." When "The Exorcist ” was released in the United Kingdom, a Christian grassroots organization called the Nationwide Festival of Light protested outside cinemas, passing out leaflets and offering spiritual counsel to the poor souls about to subject themselves to the film. "The Exorcist" also inhabits a prominent position in the psyche of the "Satanic Panic," a moral cultural movement that drummed up fear and paranoia over the supposed harm being done to children in imagined satanic rituals. It's ironic that the same moralistic groups that expressed concern over protecting children were the same folks who sent Regan actress Linda Blair death threats.

All told, despite its traditionally conservative thesis (faith good, devil bad), "The Exorcist" still drew the ire of hand-wringing moralists and concerned religious folks alike. You can't win them all.

Audiences would have to wait nearly 20 years for another good Exorcist film

The cultural impact of "The Exorcist" cannot be overemphasized. William Friedkin's 1973 film was the blockbuster of its day, setting single-week ticket sales records left, right, and center through carefully calibrated screening availability. The film also enjoyed a reputation for eliciting visceral reactions from its audience members. Whispers of vomiting, hysteria, and fainting spells are a great way to get butts in seats, it turns out. And 10 Oscar nominations later (including Best Picture), "The Exorcist" could claim both box office and critical infamy.

For fans of the film, the follow-up, "The Exorcist II: Heretic," was something of a disappointment ... to put it lightly. There are those today who would love to see a critical re-evaluation of John Boorman's 1977 misfire, sure. But the far more optimistic sequel's betrayal of the dark spirit of the original film was, in Boorman's own words, a mistake. As he put it (via Film Freak Central), "I denied [audiences] what they wanted and they were pissed off about it — quite rightly."

Then, 17 years after the release of Friedkin's original film, "The Exorcist" scribe William Peter Blatty came to the rescue. Blatty only directed two feature films over the course of his career, and one of them was "The Exorcist III," an adaptation of "Legion," his sequel to the original "Exorcist" novel. Shifting the narrative focus to William Kinderman (played here by George C. Scott), "The Exorcist III" follows the lieutenant's investigation into a string of Zodiac Killer-like murders, which seem to point him improbably back to his deceased friend, Father Karras.

The film has been praised by horror fans as a "masterpiece" that weaponizes the power of suggestion rather than indulging in excessive gore. While your mileage may vary depending on your bloodlust, "The Exorcist III" is a worthy follow-up to Friedkin's original and a breathtaking piece of genre filmmaking in its own right.