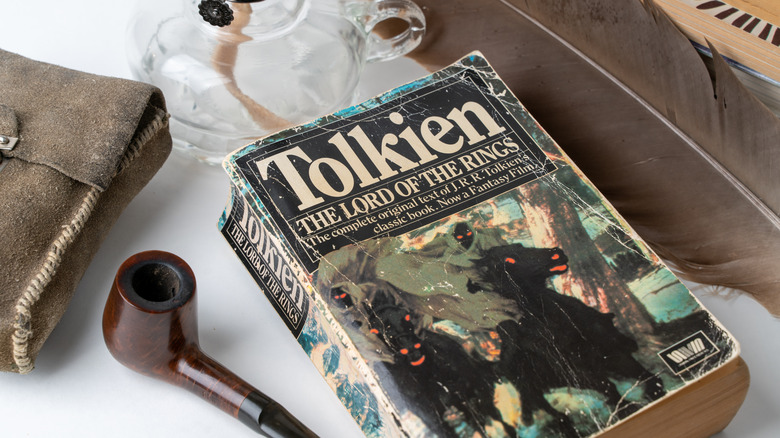

Bizarre J.R.R. Tolkien Adaptations You'll Never Get To See

J.R.R. Tolkien's vast and beloved Middle-earth legendarium has been portrayed on screen many times over the years. The earliest adaptations of Tolkien's works were produced nearly half a century ago: in 1977, Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass released an animated version of "The Hobbit," while Ralph Bakshi directed an animated adaptation of "The Lord of the Rings" a year later. Rankin/Bass would later return to Middle-earth for 1980's television film, "The Return of the King."

A few decades later, Peter Jackson directed a live-action "Lord of the Rings" trilogy; you probably know how that one went down. Jackson's movies were an instant hit, accruing a total of 17 Academy Awards and, according to Box Office Mojo, earning nearly $3 billion worldwide. The "Hobbit" movies that followed weren't quite so well received by critics or fans, though they more than matched their predecessors' takings at the box office. Now, of course, Amazon Studios is bringing the Second Age to life with "The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power," while New Line Cinema is set to return to Peter Jackson's Middle-earth with 2023's "The War of the Rohirrim."

With all this in mind, it may come as some surprise to find that Tolkien's world was once considered nigh-on unfilmable. It certainly didn't help that a litany of studios, producers, directors, and even rock stars attempted — and failed — to bring Middle-earth to life for years. Here are a few of the bizarre J.R.R. Tolkien adaptations you'll never get to see.

Filming the unfilmable

To gain a greater understanding of the context in which Hollywood attempted to film J.R.R. Tolkien's novels, it might be worth hearing from the man himself. In 1968, The Telegraph published an interview with Tolkien (via The Tolkien Society), in which he expanded on his views regarding the rights to adapt his world for the screen.

The article mentioned that Tolkien received "innumerable offers for film rights, musical-comedy rights, TV rights, [and] puppetry rights" for 'The Hobbit' and 'The Lord of the Rings,'" from a puzzle company looking to release a Ring-based puzzle to a soap-maker that wanted to "sculpt Ring characters." Notably, Middle-earth fans at the time weren't exactly supportive of these ideas — the article cites one 17-year-old fan who wrote to Tolkien: "Don't let them make a movie out of your Ring. It would be like putting Disneyland into the Grand Canyon."

For his part, it seems that Tolkien agreed, albeit for slightly different reasons. "You can't cramp narrative into dramatic form," he told the publication. "It would be easier to film 'The Odyssey.' Much less happens in it. Only a few storms."

Middle-earth's maestro wasn't exactly on board with selling out, then, but that did little to dissuade a number of interested parties. In fact, the first adaptation of Tolkien's mythos was proposed in 1938, just a year after the release of "The Hobbit."

Walt Disney's Middle-earth

Nowadays, it seems like nearly every major movie and television franchise in existence falls under the jurisdiction of the House of Mouse. Everything from the Marvel Cinematic Universe to the "Star Wars" galaxy to Pixar Studios to the Muppets is owned and controlled by Disney — and there was a very brief period in which the company considered staking a claim in Middle-earth.

According to Brian J. Robb and Paul Simpson's book "Middle-earth Envisioned: The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings: On Screen, On Stage, and Beyond," a Disney animator suggested in 1938 that the company could combine elements of "The Hobbit" with Richard Wagner's legendary "Ring" cycle of musical dramas for a segment in the animated movie "Fantasia." Disney also tried and failed to produce a film of "The Hobbit" during the 1950s, while Disney animator Wolfgang Reitherman once claimed that Disney also considered adapting "The Lord of the Rings," but decided it was too "long and unwieldy."

This may be for the best, because Tolkien truly detested Disney. In Letter 13, written in 1937, the author insisted that any illustrations for an American publication of "The Hobbit" not be influenced "by the Disney studios (for all whose works I have a heartfelt loathing)." Tolkien echoed these sentiments in a later letter, written in 1968. "I recognize [Disney's] talent," he wrote, "but it has always seemed to me hopelessly corrupted. Though in most of the 'pictures' proceeding from his studios there are admirable or charming passages, the effect of all of them to me is disgusting."

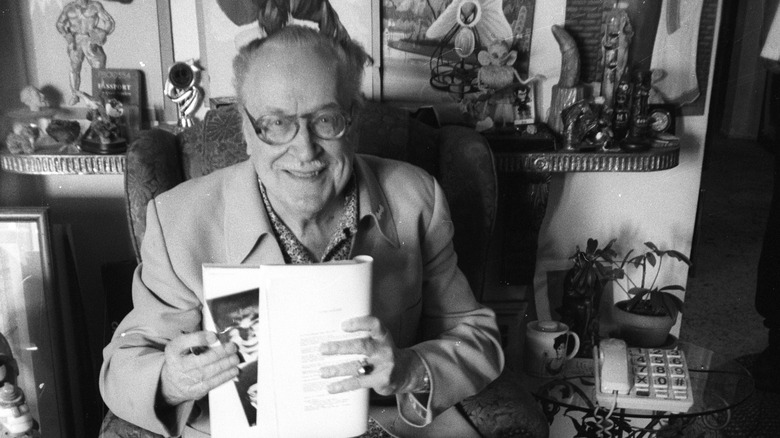

The Ackerman-Zimmerman script

Tolkien's first positive response to an attempted Hollywood adaptation of "The Lord of the Rings" came in 1957, when, according to "Middle-earth Envisioned," American sci-fi agent and editor Forrest J. Ackerman, producer Al Brodax, and writer Morton Grady Zimmerman approached the author with their idea for an animated Middle-earth movie.

Tolkien was initially impressed by their "astonishingly good pictures," in the style of celebrated literary illustrator Arthur Rackham, "rather than Disney." He was less impressed by the proposed storyline, however, which featured a "blurring of climaxes," "general degradation," and far too many eagles. Nevertheless, the rights were optioned to Team Ackerman, mostly because Tolkien believed he could acquire either "very profitable terms" or an author's veto on "objectionable features" in the script.

Soon after, Zimmerman sent Tolkien a detailed treatment of his "Lord of the Rings" story. Tolkien's response, written to Ackerman in Letter 210, was anything but approving. He complained about Zimmerman's rampant carelessness with the narrative, which seems to have contained the kinds of creative liberties that would detonate the internet nowadays. But Tolkien's greatest criticism had to do with the tone, which showed "a preference for fights" and "no serious attempt to represent the heart of the tale adequately."

In the end, the Ackerman project died an ignominious death: the project was shut down after his request for a rights extension "was not accompanied by a suitable rights payment." The whole ordeal left Tolkien forever wary of future attempts to adapt his writing.

Gutwillig and Gelfman

The Ackerman-Zimmerman attempt at "The Lord of the Rings" did not dissuade Tolkien entirely, however. "Middle-earth Envisioned" mentions that, in 1959, author Robert A. Gutwillig approached Tolkien about obtaining filming rights for the novel. Gutwillig was hardly a literary heavyweight, but his novel "The Fugitives," published the same year he wrote to Tolkien, was praised by the New York Times as being "sharply satirical" and "deeply penetrating."

Tolkien replied to Gutwillig, pointing out that he had "given a considerable amount of time and thought" to a film version of "The Lord of the Rings," and that he had both ideas for the project and "some notion of the difficulties involved." A year had passed since Letter 210, but the specter of Morton Zimmerman clearly still loomed.

Tolkien nevertheless undertook to meet with Gutwillig's agent, Sam W. Gelfman. Their meeting reportedly went well: Tolkien liked Gelfman and proved amenable to his suggestions and proposals, and so he referred the agent to Allen and Unwin, his publishers. Sadly, nothing further came of Gutwillig's project, which seemingly fell apart before it could ever get going.

The Beatles present: The Lord of the Rings

The whole world was gripped by Beatlemania in the 1960s. Perhaps inevitably, the runaway success of the Fab Four's music was accompanied by a number of live-action films, including "A Hard Day's Night," "Help!" and "Magical Mystery Tour." It was during this period that The Beatles attempted to get a "Lord of the Rings" movie off the ground.

According to "Middle-earth Envisioned," John Lennon in particular was a fan of Tolkien and believed that he and his bandmates could very well star in the picture: Lennon as Gollum, Paul McCartney as Frodo, George Harrison as Gandalf, and Ringo Starr as Sam. They even approached Stanley Kubrick, who had just directed 1964's "Dr. Strangelove," to helm the project.

If nothing else, a "Lord of the Rings" movie starring The Beatles and directed by one of the greatest directors in history would certainly have been interesting — but it simply wasn't to be. For one thing, Kubrick wasn't interested. But it appears that Tolkien himself drove the final nail into The Beatles' coffin. In 2021, Peter Jackson told the BBC that the author himself had refused the Fab Four permission to make their movie. "He didn't like the idea of a pop group doing his story," Jackson claimed, before wondering how the project might have turned out. "What would The Beatles have done with a 'Lord of The Rings' soundtrack album? That would have been 14 or 15 Beatles songs that would have been pretty incredible to listen to."

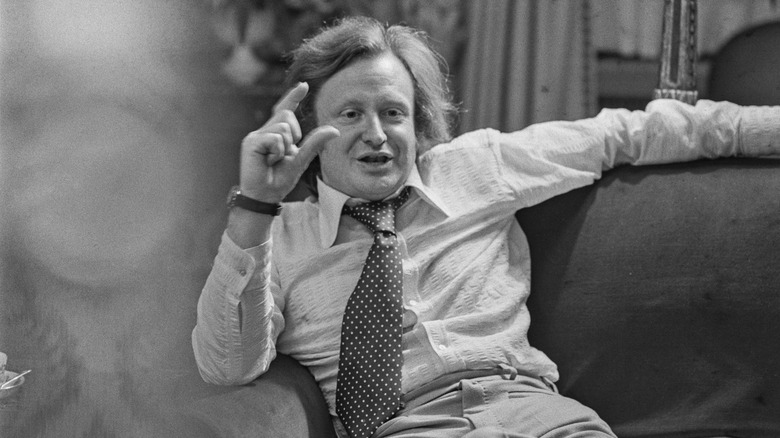

The strange adventures of John Boorman

In 1967, United Artists acquired the film rights to "The Lord of the Rings." Tolkien was 75 years old by that point, and, as "Middle-earth Envisioned" tells it, had decided that he would not live to see his novel appear on screen. As such, he didn't particularly care who ended up with the rights.

A few years later, United Artists hired director John Boorman to helm a live-action adaptation of "The Lord of the Rings." Boorman would later become renowned for movies such as "Deliverance" and "Hope and Glory," but at that time he had directed just a handful of features, including 1967's "Point Blank." Screenwriter Rospo Pallenberg worked with Boorman to figure out how best to bring Middle-earth to life on the silver screen. He ended up writing a 176-page script for their movie, which would likely have run almost three hours with an intermission halfway through. The details of the screenplay range from fascinating to mortifying: it featured a Kabuki-style theatrical performance of Middle-earth's history, a sex scene for Frodo and Galadriel, and a battle of "words and ideas" fought between Gandalf and Saruman.

Boorman's film was destined to fail, however. According to Gizmodo, United Artists ran out of money after a number of "commercial setbacks," finally deciding not to move forward with the project. The good news, though, is that the script still exists online — just in case you want to better imagine a movie in which Aragorn and Boromir kiss, beekeepers defend the walls of Minas Tirith, and Merry blinds a horse with a frying pan.

Ralph Bakshi's The Lord of the Rings, Part 2

The title of Ralph Bakshi's animated Middle-earth movie, "The Lord of the Rings," is something of a misnomer, as it only tells the story of "The Fellowship of the Ring" and certain aspects of "The Two Towers." Upon its release in 1978, "The Lord of the Rings" was a considerable financial success, earning $30 million worldwide off an estimated $4 million budget. But it was met with poor reviews from fans: According to "The Animated Movie Guide," Tolkien aficionados were not pleased at all with what they considered to be subpar visuals and the fact that the movie ended halfway through the story.

An article later published in Cinefantastique claims that Part 2 of Bakshi's tale was greenlit for release in 1980. Initially, the film's creators were optimistic — Bakshi predicted that the film could make some groundbreaking new advances in animation — but a sequel to "The Lord of the Rings" simply never materialized. Screenwriter Peter S. Beagle later recalled that it all came down to creative differences between Bakshi and producer Saul Zaentz. Bakshi in particular believed that the first movie simply hadn't been as good as it could have been.

In 1980, the production company Rankin/Bass, which had made 1977's animated "The Hobbit" movie, released "The Return of the King" as an ABC television special. While this had nothing to do with Bakshi's half-completed project, the story does pick up around the same point that "The Lord of the Rings" ended, providing fans with a kind of unofficial conclusion to the 1978 movie.

Treasures Under the Mountain

According to TheOneRing.net, Russian director Roman Mitrofanov set out in the early 1990s to bring an animated adaptation of "The Hobbit" to life, but the project fell apart when the Soviet Union crumbled in 1991. Here's the fun part, though: the movie's six-minute prologue, depicting the fall of Erebor and Dale, still exists online. The sequence opens on a party in Dale, in which the townsfolk cavort and dance in the square. Enter Smaug. The great dragon destroys Dale and takes Erebor for his own; as the snow falls, the scene cuts to a meeting of the dwarves and Gandalf, who suggests they hire a burglar to accompany them on their quest for vengeance.

You'll probably know all this, of course, if you've already seen or read "The Hobbit." But the Mitrofanov prologue features a couple of interesting quirks, not seen in the novel, that Peter Jackson appears to have referenced in his movies. For example, the people of Dale fly dragon kites, just like they do in "An Unexpected Journey" — in fact, the moment in which the kites struggle as Smaug approaches is more or less identical to a shot in Mitrofanov's version, when darkness falls on the town. While the animated Erebor looks much different to Jackson's version, the sight of Dale covered by snow will look all too familiar to fans of the latter. You can only imagine how the "Hobbit" movies might have looked if Mitrofanov had finished his adaptation.

The Weinstein production

An 2021 essay written for Polygon by film critic Drew McWeeny tells the story of the war between Jackson and disgraced producer Harvey Weinstein over the "Lord of the Rings" movies. Having worked with Jackson on films such as "Heavenly Creatures" and "The Frighteners," Weinstein acquired the rights to "The Lord of the Rings" from Saul Zaentz and hired the director and his screenwriting partner, Fran Walsh, to make it a reality.

The first outline Jackson and Walsh prepared for Miramax, Weinstein's company, told a story across two pictures: "The Fellowship of the Ring" and "The War of the Ring." McWeeny writes that the original scripts felt like "watching the eventual movies on 1.5x speed playback" — characters such as Arwen, Merry, and Pippin get little development, the Shire scenes are brief, and the elves are met only briefly.

Weinstein wasn't exactly cooperative during pre-production, and eventually restricted Jackson to a measly $75 million budget. So Jackson and Walsh decided on a desperate gamble to save their movie: they leaked the script for their project to McWeeny, who then reviewed it on Ain't It Cool News.

Weinstein pushed Jackson even further after that, demanding "The Lord of the Rings" become one four-hour film. Jackson refused and Weinstein conceded, giving up the movie on the condition that Miramax be repaid everything that had already been spent on development. Luckily, New Line execs Bob Shaye and Michael De Luca rode in to save the day, committing to the project and insisting on three "Lord of the Rings" movies. The rest, as they say, is history.

Guillermo del Toro's Hobbit

J.R.R. Tolkien and Guillermo del Toro fans alike were overjoyed to learn in 2008 that the acclaimed fantasy and horror director had been hired to helm New Line Cinema's "Hobbit" movies. They were somewhat less overjoyed to learn, two years later, that del Toro had left the project, citing production delays and other commitments as the reasons for his departure. For better or for worse, the "Hobbit" trilogy would eventually be directed by Peter Jackson.

So how would Del Toro's Middle-earth saga have played out? Well, for one thing, it was intended to take place over the course of two movies rather than three: "An Unexpected Journey" and "There and Back Again." In 2011, New Yorker writer Daniel Zalewski visited del Toro's home and got a glimpse at how the films may have looked. He described seeing a sketch of Smaug the dragon that resembled a "flying axe" and drawings of other new monsters such as an armor-plated troll, while del Toro elaborated on making Middle-earth look more like paintings out of a book than the realistic New Zealand landscapes that Peter Jackson utilized.

Of course, it's impossible to say whether Del Toro's "Hobbit" movies would have been any better or worse than Jackson's, but one thing is for sure: they clearly would have made for one heck of a trip.