Everything Milk Doesn't Tell You About The True Story

"Milk," a biopic about gay rights activist Harvey Milk, opened in theaters in 2008 to critical acclaim. The film garnered accolades and awards for Gus Van Sant's direction, Dustin Lance Black's screenplay, and Sean Penn and Josh Brolin's leading portrayals of Harvey Milk and Dan White, respectively. The movie tells the true story of the man who made history by becoming America's first openly gay politician, solidifying his legacy as an icon for the LGBTQ+ community.

"Historical accuracy was always a top priority," screenwriter Dustin Lance Black stated in the published edition of "Milk: The Shooting Script." Of course, any adaptation is inevitably going to include certain inaccuracies and omissions. It's more important than ever to celebrate, uplift, and examine LGBTQ+ cinema and the ways in which it reflects the real world (or doesn't), and this modern classic is ready for a second look. Here are some noteworthy departures the Oscar-winning film makes from the true story of Harvey Milk.

Dan White's sexuality

The film suggests that Dan White may have been a closeted gay man, whose tormented mental state and confusion over his sexual identity, along with his financial and political troubles, played a role in his sudden homicidal behavior when he assassinated Milk in 1978. This portrayal of Dan White heavily resembles Colonel Frank Fitts in the 1999 movie "American Beauty," a character whose homophobia is fueled by his own repressed homosexuality, eventually driving him to commit murder. Coincidentally, "Milk" producers Bruce Cohen and Dan Jinks also produced "American Beauty."

The way Van Sant stages the characters of Milk and White together seems to convey a certain intimacy deeper than friendly cordiality between two peers. Penn and Brolin's chemistry further adds to this, with Harvey possessing a sense of empathy and understanding for Dan. In the film, when Harvey's entourage questions Dan White's significance in Harvey's political agenda, Harvey confides that he thinks Dan White "may be one of us," empathizing with Dan about "living the lie," which he claims to see in Dan's eyes. In all of the scenes featuring the two characters together -– be it in the church scene during the christening of White's son, or White's drunken confrontation with Harvey during the latter's 48th birthday party -– it's becomes obvious to viewers that their relationship has more layers than mere political and ideological disagreements.

Although it's possible that White had sexual insecurities or was secretly gay, there isn't any real-life evidence or suggestion to support this speculation, nor the idea that White murdered Milk as a result of his repressed homosexuality. Dianne Feinstein, White's colleague, friend, and then-President of the Board of Supervisors, reflected in 2008 (via SFGate), "This had nothing to do with anybody's sexual orientation ... it had to do with getting back his position."

Harvey planted the dog poop he stepped on

In the film, Harvey realizes that in order to beat Proposition 6 (the ballot initiative aimed at banning gay men and lesbian women from working in California's public schools), he'd need to challenge the proposition's sponsor John Briggs to a public debate. However, Harvey decides that to get Briggs' attention, he needs to attract greater exposure to himself using a more populist strategy, by resolving the number one problem faced by San Francisco citizens: dog feces.

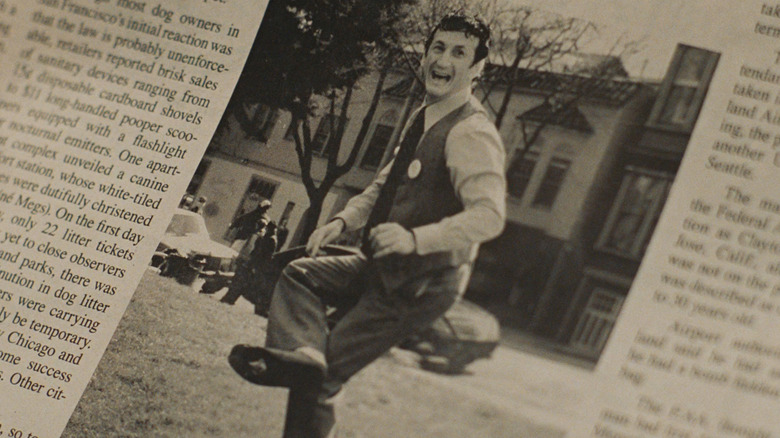

And so, one of the first things that Harvey does after being sworn in on the Board of Supervisors is to promote a new city ordinance (dubbed the "pooper scooper law") that mandates dog owners to scoop up their pets' waste. Harvey invites the press to a photo-op of himself scooping up dog feces at a public park, where he accidentally steps on some of the excrement and lifts his foot to show the cameras.

While most of the events shown in the movie about the ordinance are accurate to what actually transpired (with Harvey successfully garnering press coverage as a result), there's one crucial aspect that the movie leaves out. In the 1984 documentary "The Times of Harvey Milk," Harvey's former campaign manager Anne Kronenberg revealed that Harvey went down to the park an hour beforehand and hid a pile of dog waste in a specific location, to make sure that he would step on it in front of the rolling cameras. Kronenberg said that Harvey was "a master at figuring out what would get him covered in the newspaper." What's notable is that the film's shooting script features a scene in which Cleve Jones (Harvey's friend and political intern) scoops and plants the dog poop in preparation for the photo-op.

Dan White's friendship with Dianne Feinstein

In "Milk," then-President of the Board of Supervisors Dianne Feinstein isn't depicted by an actor, instead only appearing in real-life archival footage. Most notably, there's the famous news clip that's played in the first few minutes of the movie, in which a shocked Feinstein announces the murders of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk, prompting raucous gasps from the reporters. Later, Feinstein was appointed Mayor of San Francisco, replacing Moscone, and eventually she was elected to the United States Senate in 1992.

In reality, while Harvey Milk had an "uneasy" relationship with Dianne Feinstein, she was close friends with Dan White. White and Feinstein aligned on a number of political issues, particularly gun control (via City Journal). White was the one who persuaded Feinstein to appoint Milk as chairman of the Streets and Transportation Committee — a position Milk wanted. "I was a friend of Dan's," Feinstein told CNN in 2017, "and I tried to some extent to mentor him." Reflecting back on the murders, Feinstein went on to say that she always wondered whether she could have prevented the killings, as she was there on the tragic day at City Hall and was the one to find Milk's body in his office.

Perhaps the decision of the filmmakers to leave out Feinstein as a character arose from the need to focus on White's apparent loneliness and his attempts at developing a friendship with Milk. This subplot of their friendship leads up to the moment of betrayal for White when Milk refuses to vote in White's favor at the Board of Supervisors. White's existing political problems and distant relationship from the other Board members had exacerbated his feelings of alienation with the job and with Milk, which ultimately led to him handing in his resignation.

Mayor Moscone and Harvey Milk's relationship with the Peoples Temple

The film omits any mention of Mayor George Moscone and Harvey Milk's relationship with the Peoples Temple, the religious organization now known to be a cult that was responsible for the 1978 Jonestown massacre in Guyana nine days before Milk's assassination. The cult had developed ties with several left-leaning politicians, including San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk, whose campaigns were supported and endorsed by cult leader Jim Jones. It was revealed in Randy Shilt's biography of Milk, "The Mayor of Castro Street," that Milk privately felt that the Temple members were odd and dangerous, cautioning his aide, "Make sure you're always nice to the Peoples Temple ... they're weird and they're dangerous, and you never want to be on their bad side."

In fact, then-city supervisor John J. Barbageleta, who was George Moscone's political opponent and runner-up in the 1975 San Francisco mayoral election, maintained for the rest of his life that the cult had committed election fraud by bussing in out-of-town church members to cast multiple votes for Moscone under the names of dead voters. After the massacre, Barbageleta's claim was corroborated by former Temple members to The New York Times. As mayor, Moscone had endorsed Jones and the Peoples Temple and appointed Jones as Chairman of the San Francisco Housing Authority Commission.

When allegations arose from former members of the church's fraud, assault, and kidnappings (reported by Marshall Kildruff for New West), Moscone refused to conduct any investigation into Jones and the Temple's activities, despite demands from supervisor Questin Kopp to do so. In his press release, Moscone said that the New West article was "a series of allegations with absolutely no hard evidence that the Rev. Jones has violated any laws, either local, state, or federal."

Dan White's chief political advisor was a gay man

Dan White's discomfort with homosexuality and gay men like Harvey Milk is frequently depicted in the movie, with his political and public rhetoric labeling gay people as "splinter groups of social radicals, social deviants and incorrigibles." From White's point of view, this seems necessary in order to appease District 8 voters, the majority of whom are white, conservative, middle-class families who are opposed to San Francisco's expanding gay community. However, his homophobia isn't as apparent in his private moments with Milk, as White tries to build a personal and professional rapport within the Board of Supervisors.

Aside from the film's suggestion that his homophobia may have been rooted in his own repressed homosexuality (or, at least, that Milk thought so), most of its depiction of White is factually accurate. He did indeed try to cultivate a friendship with Milk, and when Milk supported a bill that White asked him to oppose, White was left feeling betrayed and disillusioned. This feeling of betrayal was further intensified when, after trying to convince Mayor Moscone to rehire him, White found out that Moscone had been advised by Milk against doing so, fueling White's anger to the point of murder.

However, the film omits a crucial detail about Dan White. Ray Sloan, White's chief political adviser and campaign manager was (and is) a gay man. Speaking with SF Weekly before the film's release, Sloan sought to dispel misconceptions about who White was and why he murdered the first openly gay man to be elected to public office -– that it came from a place of betrayal, not homophobia. Sloan's own orientation was not an issue for White. "It was never discussed, even though he had to have known about it," Sloan explained. "It just wasn't an issue."

The Twinkie Defense

The title cards at the end of the movie state that Dan White's attorneys claimed that White's consumption of junk food led to a chemical imbalance in his brain that led him to kill Mayor Moscone and Harvey Milk. Since then, this defense strategy has been mockingly referred to as the "Twinkie Defense," a term that journalists used during White's trial and has since spread to describe various improbable legal defenses. The popular usage of the term has resulted in the common misconception that the defense claimed that White committed the murders as a result of a sugar rush from eating too many Twinkies, which led to White getting away with a light sentence of seven years on a basis of "diminished capacity." The verdict had resulted in uproar among the gay community in San Francisco, setting off the violent "White Nights Riots."

Twinkies were actually only addressed in passing throughout the trial, and White's defense team argued that excessive junk food consumption was a symptom of White's depression rather than a cause. Psychologists employed by White's defense argued that his behavioral changes, such as quitting his job, distancing himself from his wife, and dietary shift from healthy foods to junk food and soft drinks, were evidence of White's clinical depression.

While this should not, in any way, justify the atrocious acts committed by Dan White, it's important to note the role that depression had played in this tragic ordeal, and the lack of adequate awareness and facilities to address mental health at the time. Less than two years after being released from prison, White committed suicide in 1985. Former Chronicle reporter Duffy Jennings, who covered the trial for the newspaper, commented on the media's use of the witty moniker of "Twinkie Defense" disparagingly. "It's not as sexy to call it a depression case," Jennings wrote (via SFGate).

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The Jonestown massacre

In omitting any mention or depiction of the Peoples Temple, "Milk" leaves out some complexities of not just the political landscape before Harvey Milk's murder, but of the fallout after. In 1978, California Representative Leo Ryan travelled to Guyana to look into the reports that members of the Peoples Temple were being held at the Jonestown settlement against their will. As he and his staff attempted to depart from an airfield, he was shot and killed by Temple members.

After Ryan's assassination, Jim Jones ordered everyone at Jonestown to commit mass suicide via cyanide-laced fruit drinks. Those refusing to drink were involuntarily injected with cyanide. This event (termed a "revolutionary suicide" by Jones) resulted in over 900 deaths, of which about 300 were children (via BBC). Americans at large and residents of San Francisco in particular were horrified by this massacre, creating a tense atmosphere that remained fresh during the unrelated killings of Moscone and Milk just nine days later, which many believe contributed directly to the "White Night Riots."

While it's understandable that including this event and its aftermath would have significantly increased the duration of the film, its absence becomes noteworthy given the film's dedicated focus on the political and cultural atmosphere in its setting of 1970s San Francisco.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The first 40 years of Harvey's life

It's almost impossible for any good biographical film to capture the entirety of its subject's life, no matter how hard the filmmakers work to do so. A feature film has its own restrictions and demands, generally needing a couple of hours to focus on a single protagonist overcoming a major conflict at a specific moment or period in their life. "Milk" screenwriter Dustin Lance Black and director Gus Van Sant chose to focus on Harvey Milk's life and political career from 1970 to 1978, emphasizing on Harvey's journey towards becoming the first openly gay man to be elected to public office, and his victory over Proposition 6. But there's a lot that's left untold about Harvey Milk's life before the eve of his 40th birthday, where the film chronologically begins.

For instance, though Milk had known that he was homosexual since his adolescence, he carried on with his life adhering to what society had expected of any man in that era, pursuing relationships with secrecy well into his adulthood. After graduating college, Milk enrolled in the United States Navy, serving as a diving officer during the Korean War. At the time, gay servicemen were prohibited from openly acknowledging their sexuality. When the Navy officially questioned him about his sexual orientation, he was forced to resign at the rank of lieutenant, junior grade, with an "other than honorable" discharge (via CNN).

Milk had been a registered Republican until the age of 42, when he first ran for a seat in the San Francisco Board of Supervisors as a Democrat in 1972. In fact, he had even participated in the 1964 presidential campaign of conservative Republican candidate Barry Goldwater. The counterculture movement of the '60s had encouraged Milk to discard his conservative stances and express his sexuality more openly. While the film makes a few subtle references about Milk's prior political affiliations, it would have been interesting to see how Harvey's views on gay rights evolved as he came to terms with his own sexual orientation.