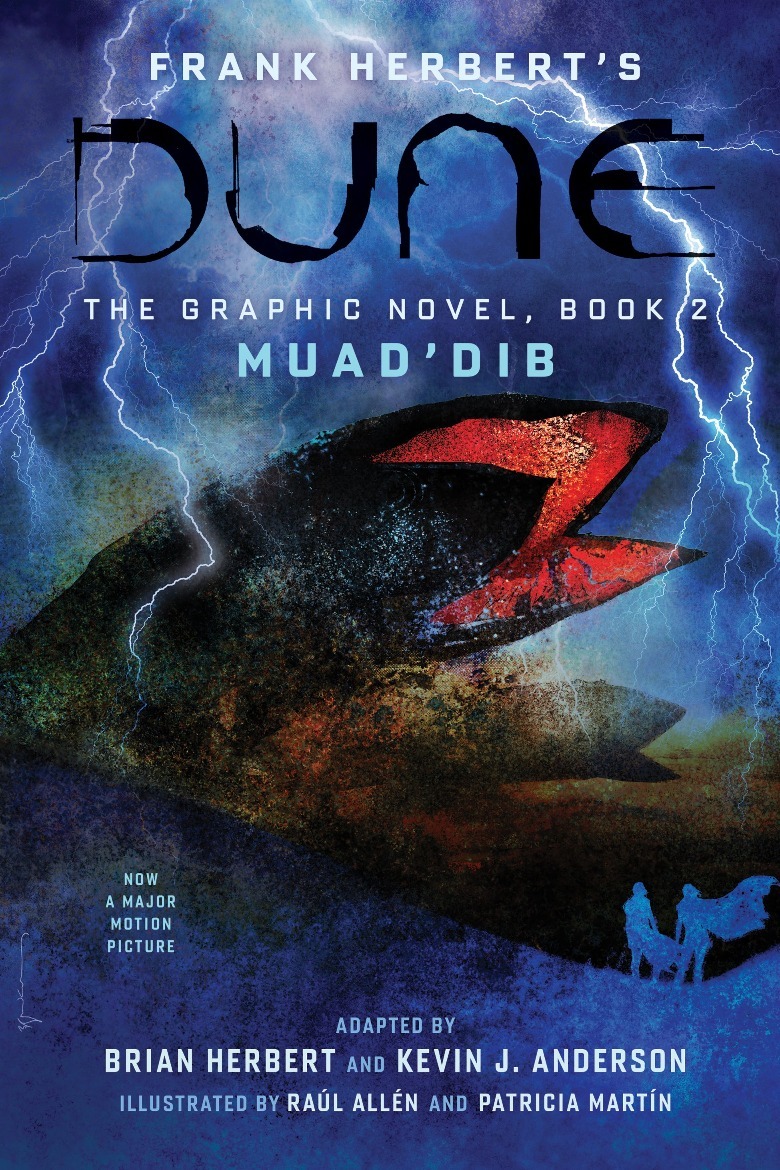

Writers Brian Herbert And Kevin J. Anderson Discuss The Enduring Legacy Of Dune - Exclusive Interview

In 1965, the world of science-fiction changed forever with the release of "Dune." Frank Herbert's seminal work tells the story of Paul Atreides, whose family assumes stewardship of a planet known as Arrakis for it's the only source of spice in the galaxy. The book has much to say concerning politics, ecology, religion, and technology, to name a few. And as the decades have gone on, it seems as though the story has only grown more relevant as wars for control of a few precious resources wage on.

Frank Herbert may be gone, but his legacy lives on and continues to evolve thanks to the tireless work of his son, Brian Herbert, as well as Kevin J. Anderson. Herbert wrote several sequels to "Dune," and Herbert and Anderson have carried on that tradition by continuing to create works based on the world he created so many years ago.

Looper had the privilege of speaking exclusively with both Herbert and Anderson to talk about their work, including the most recent "Dune: The Graphic Novel, Book 2: Muad'Dib," which brings the original source material into a new medium. They spoke at length about "Dune" and how the story continues to resonate with audiences all these years later.

Inspiration in Dune

To start, I'd like to ask what books outside of the Dune series have served as the biggest inspiration to you both?

Brian Herbert: I tend to read nonfiction, so I don't really like to quote too much about fiction. I read a lot of history. That's what I'm reading every day. "Dune" is the greatest — not just science-fiction — it's a great American novel, and it'll be read for 500 years. It's so incredible. I wouldn't want to disparage it by saying that Frank Herbert was influenced by anything, and I certainly wasn't influenced by anything else.

"Dune" is pretty unique. It calls on old myths, but [Frank Herbert] did the same thing that I just told you. He would read encyclopedias, literally. He'd look something up. He was in the Smithsonian Library — sometimes he would do that in Washington, DC — he'd look something up and he couldn't avoid the temptation of reading what was on the other page. He absorbed everything. I do that on a smaller scale, but I do absorb a wide range of things.

Kevin J. Anderson: I do that myself, but I'm not Frank Herbert. To answer the question, "Dune" is unquestionably my favorite science-fiction novel. And as a –

Herbert: Ah, he qualified it.

Anderson: As a writer, I like to read outside the genre so that I can draw some of the best things from great works and other genres. I like these really big sprawling stories, like "Dune" is. I really love like James Clavell's "Shogun," and I love Larry McMurtry's "Lonesome Dove," and I love Mario Puzo's "The Godfather." Stephen King's "The Stand" is another one of my very favorite giant novels.

Herbert: On "Lonesome Dove," I showed Kevin the 1948 movie "Red River," which has a lot of similarities. Kevin was surprised, but I guess everybody's influenced by everything.

Anderson: You draw from it. That's the thing. It's a conversation. It's not stealing from somebody when I read "Lonesome Love," and it influences something that I put into a scene in a "Dune" book that Brian and I are writing. It enriches the final work.

Here's an example. In the 1980s, the biggest, hottest genre was epic quest fantasy novels, and everybody wrote a fantasy trilogy. It seemed to me that a lot of those writers only read other epic quest fantasies, that they kept reading the same thing that they were writing. It's like eating leftovers all the time. I [don't] want to read the stuff that I'm writing. I want to read outside that, just like Brian reads nonfiction.

Oh, and one last thing. ... Like I said, I love "The Godfather." I love "Lonesome Dove," they're giant books, and "Shogun." I've only read those once. My last count, I think is 23 times I've read "Dune." I don't think I'd live long enough to read "Lonesome Dove" 23 times, but "Dune" is something that we go back to again and again.

Brian and I just did a very detailed scene-by-scene graphic novel adaptation of Frank Herbert's original "Dune." Abrams Books is about to publish the second volume of that. By doing that, [it] was like a deep dive, like a deep x-ray into the novel. I still came up with all kinds of things that [made me think], "Oh, that connects with something else that I never even saw before." It's a brilliant book. Brian and I admire it.

Herbert: That's true of great movies, too. You can watch a great movie 23 times, and you'll see something in it that you didn't notice before. You follow a thread sometimes, and you'll see things that you weren't aware of. It's amazing, and "Dune" is like that. There's so many things in it that we find each time we look at it.

Adapting such an important story

That segues nicely into my next question. Looking back to "Dune Volume One," the graphic novel, how did you go about adapting the story and making it feel fresh within this new medium?

Herbert: I gave Kevin a detailed outline of the whole novel, but Kevin has more experience in comics and graphic novels. He knew what to pick out of my outline and what to pick out of "Dune" itself. Go ahead, Kevin, you need to get the core of it.

Anderson: We went straight to the novel, and we decided right from the beginning that this wasn't going to be "our interpretation" of "Dune." This was going to be Frank Herbert's novel, converted into a graphic novel, which meant the way he wrote it. Chapter 1is Chapter 1 and the scenes and the way he laid them out.

It gave us this great perspective on understanding how difficult the novel "Dune" is to convert into a visual medium. Many times, people have trouble with films, because there's so much information that needs to be conveyed before you can really get going in the story. We did it specifically the way Frank Herbert wrote it in the graphic novel.

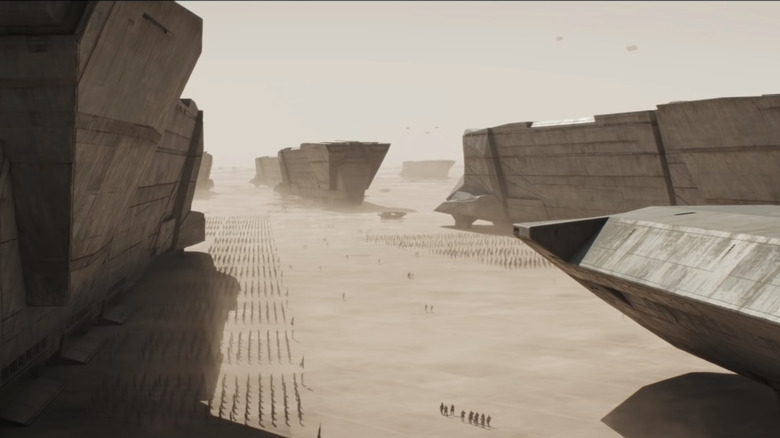

One of the other real advantages that Abrams gave us is, unlike monthly comic books, [those] are hard and fast, 22 pages and then there's no flexibility in that. It's got to be 22 pages, and that's the way it goes. With the three-volume graphic novel from Abrams, they gave us a general [guideline to] try to fit it in with this many pages, but we were able to write it exactly the length that we needed to convey it in a graphic novel, which is a freedom that a lot of comics writers don't really get. We got to put in however many two-page spreads we wanted and giant panels with sandworms and the big desert landscapes. It turned out beautifully.

Herbert: It did, and that actually reflects some of the problems that Dad had. He didn't care about genre when he was writing back in the '50s. He wrote anything. He wrote mysteries, he wrote first-person accounts of going to Mexico. He wrote things that were any length. His agent told him, "You're not writing something that can be published in the existing marketplaces."

Here comes "Dune," which was a big door-stopper at the time. When novels were 50,000 words, here's a 200,000-word novel. It had to be published by Chilton, who was used to doing these huge auto repair books for Ramblers and things. Dad was not ... commercially in touch with what he needed to do, but he insisted that he had something with "Dune." He knew it, and my mother knew it, and he continued with it. I thank God he did.

There's so many authors, and there's one that I've heard of that's got millions of words unpublished, millions of words written. There's so many people that have written great things that never quite find the eye of someone in a powerful position. You wonder, "What is out there that we haven't seen?" Well, "Dune" could have been that. In fact, more than 20 publishers turned it down in New York and most of the East coast.

One of the editors said, "I may be making the mistake of my career in turning 'Dune' down, but I can't get through the first 100 pages without being confused and irritated." Kevin knew all that when he was setting up the priorities, and Abrams and everybody has done a wonderful job, the artist. Look at it. It's beautiful.

Anderson: We don't have the disadvantage either, that we're ... Frank Herbert was coming in cold. Nobody knew anything about Dune. By now, we hope the people who pick up the graphic novel are coming in, either having read the original novel itself, or they've seen the movie, and they want to see how the novel was laid out. We don't have to entice the audience as much. They're already on our side and they want to see the beautiful graphic novel.

Political themes of Dune

How do you feel the political themes within the "Dune" series translate now, compared to when the original book came out so many years ago?

Herbert: They're classic, aren't they? The warnings against a charismatic leader — I don't want to name the current leaders, but at the time Dad was writing "Dune," he gave the example of John F. Kennedy, who was a decent enough person, but his followers would follow him right off the edge of a cliff. Dad was very concerned about a charismatic leader like that, and look at Paul Atreides in "Dune Messiah," where Dad flipped the myth of the heroic leader. We have to question our leaders, and there's plenty of examples of that now, without naming anybody.

Anderson: There's also the obvious ones of ecological messages. Now that we're all faced with the threat of climate change ... especially in the later "Dune" novels that Frank Herbert wrote, there's [content] all about terraforming and climate changing and what happens if you screw up the Earth by human intervention. That's such a vital theme now.

Despite being this very valuable thing that makes space transportation possible, it's only on this hellish desert planet. There's parallels to oil and Saudi Arabia and stuff there, but his original thing was worr[ying] about hydraulic despotism as in people controlling the resource of water. It's such a vital thing. I saw a report a couple nights ago about how the water rights to the Colorado River, that it's basically oversold three times what the amount of water is. It's having devastating effects here in the American Southwest.

Herbert: Whatever the limited resource is, there's going to be somebody trying to control it.

Anderson: In fact, one of the really great things about "Dune" is, you read it at one point and you go, "Wow, this is so relevant to whatever news story I just watched." Then you read it five years later and [you say], "Wow, it's so relevant to an entirely different way to an entirely different news story." That's happened to me five or six times when I've read it, that it seems to be written to match today's headlines, even though it was written in the '60s.

Feminism in Dune

Herbert: Look at the strong female characters. Now, women are speaking up where they didn't before. Dad had strong female characters that he wrote about in the early '60s. He was even ahead of Gloria Steinem ... He was in touch with the advancement of humankind. That's what "Dune" is all about. It's about human potential.

Anderson: Brian makes a really good point that isn't mentioned often enough now, that Lady Jessica in the novel "Dune," she's a real character. She's got real thoughts, and she's really strong and she solves problems, and she's really intelligent. When this was written in 1963, when I first started being serialized, the female character in science fiction was this adoring lab assistant who said, "Please doctor, explain it to me." That was the extent of female participation.

Frank Herbert transformed female characters in science fiction, and by having Bene Gesserit, this organization of women who are so powerful, they're running the galaxy behind the scenes. In early science fiction, it would be the Tiger Queen of Venus or something like that. [Those were] not strong female characters, and Frank doesn't often get the credit for being one of the pioneers of strong female characters.

Herbert: Some of that might come from Dad's connection with Native Americans.

I spoke to a Native American myself that knew my father, and he talked about the complexities of the human female, that she's the most complex organism on the planet, is the way he put it. Dad extrapolated that into this complex organization of women. In doing that, in a sense, you can look at doing and say the women are more steady, and they're even more important than the men here, which is a reversal from what we've been taught throughout history where men rule and men kill and create all these wars.

Dune maintaining relevance

Along those lines, many people were introduced to "Dune" for the first time with the 2021 film. Brian, what do you think your father would've thought of this universe he created still being relevant and beloved almost 60 years since the first book came out?

Herbert: He would be amazed, but he knew it. He knew it all along, didn't he? He knew it even when the rejection letters were pouring in.

"Dune" has incredible legs. It keeps going. Energizer bunny. It keeps going and going. Right now, it's probably the pinnacle of an awareness around the world about "Dune." That's what Kevin and I have tried to do. We've tried to show the world what Frank Herbert came up with. We're working in his universe. We're not under any illusions about anything else. This is Frank Herbert's genius that's created all this. Everything you can think of to do with the "Dune" universe has to do with Frank Herbert and how people see the "Dune" universe and how they translated into various mediums, whether it's graphic novels, comics, books, movies, TV. It's an incredible thing.

Now there's games, video games, tabletop games, but we're always trying to protect the "Dune" canon. We try to make sure that even games are authentic and stick to the "Dune" canon. We do the best job we can on that.

Anderson: Notice how Brian's very artfully resisted saying that we're playing in his sandbox.

Actually, that's a question for me to you, Brian, because we haven't talked about it. Your dad knew that this book was really good. Sometimes, a writer's work takes off and they go, "How did lightning strike on that one?" Frank must have ... this was a giant book at its time. He wrote a book three times as long as the normal science fiction book was, and it deals with politics and religion and ecology, which is not what your teenage science fiction fan wants.

Either Frank was inspired, and he wrote whatever he wanted, which isn't actually part of the answer, but he must have. In order to do something this outside of the box, he must have really believed in it, or why put that much work into it? It's not a simple book, so he must have known.

Herbert: He believed in human potential and mythology. Look at the mythological characters, which go to ridiculous extremes of human potential. Dad had his own mythology that he was creating. You've got these Mentat that are like human computers. You've got the Bene Gesserit that are breeding for a superhuman Kwisatz Haderach. You've got the Suk doctors that are the epitome. The sword masters in "Dune" are the best there ever was. It goes on and on.

He believed in the potential of humankind. He was an optimist about the potential for humans, but he was also a realist. He was a Republican, which a lot of people can't believe. He was a Republican speech writer back in the '50s, but he also led anti-war movements. He saw a very big picture of humankind with the good and the bad, and that's what "Dune" is all about. It's about Frank Herbert's huge mind, a mind that expanded across the universe. Look at his "Dune" universe. Amazing.

Challenges going into Dune Volume 2

Moving on to "Dune Volume Two," were there any challenges to adapting the source material to a graphic novel setting?

Anderson: I'll take this one. "Volume Two" was easier because "Volume One" did all the heavy lifting of introducing all the concepts, and the story is really rolling by "Volume Two." Paul and Jessica run through the desert, and they meet up with the Fremen, and the Harkonnens are wrapping up after the battle of Arrakeen. At this particular volume, it seemed to go even faster. If you compare the artwork between "Volume One" and "Volume Two," Rowland, Patricia, our two artists, they had a little more elbow room. It's bigger panels and more dramatic in this volume.

Our job was easier this time. There's Feyd in the gladiator arena and big sandworm attacks and Harkonnen battles. This one was particularly exciting. I don't want to spoil for "Volume Three" because that one's even bigger yet. So they just keep building.

Were there any changes you had to make to the story to make it work within this medium?

Anderson: Nope, that was our mission from the beginning that we were going to do it the way that Frank Herbert wrote the novel. Sometimes, that means there are a couple of pages that are in talking heads in a lot of discussions, but in the comic medium, you can do interesting visual stuff while a conversation is going on. When you're reading, it's all in your imagination.

Say you have a conversation between Jessica and Stilgar that goes on for pages and pages. You don't just do panels of Jessica talking, then Stilgar talking, then Jessica talking. You mix that up with the head shots, but then you can do an outside desert scene and then you can do Fremen and the Sietch, and you can do them walking through the caves.

If you're paging through the book, it still looks like a striking, graphic couple of pages, although what's really happening is they're just talking for a couple of pages. That's the great [thing about the] medium of graphic novels is that you can put beautiful pictures, even when there's a lot of words happening.

Herbert: Dad was a professional photographer for a long time, so he liked to see things through the lens of a camera. Take the, probably, most famous talking head scene, the banquet scene. There's actually a lot going on in that, not just talking heads at a table. There's poison snoopers around, there's Duke Leto saving water squeezings for the people.

There's this dangerous Liet-Kynes that the smuggler is afraid of — or maybe it's the water seller, that one I gotta look up — all this tension and fear going on at a table with people eating and drinking. Dad said he liked to lay out the relationships in a scene like that; he liked to lay out the good and the bad, the aggressor and the person that's going to flee the aggressor. It's all in there. It's this layer underneath the fine meal.

Readers getting into Dune for the first time

How would you convince someone to pick up the "Dune" series who may feel intimidated, knowing there are so many reference points to draw from?

Herbert: Kevin and I were in San Francisco on Market Street, and we gave a talk to a big audience. It was probably 23 years ago. We talked to a big audience at the bookstore on Market Street, right in downtown San Francisco. There was an elderly gentleman sitting over at the side. He never heard of "Dune," but as you do in these situations, sometimes you'll join a crowd of people and see what's going on.

He asked a question, and at the end of it, he said, "Mr. Herbert, what would you say to convince me to read 'Dune?' Why should I read 'Dune?'"

I said to him, "Well, if you don't read 'Dune,' you're missing a huge part of our culture. It's not just science-fiction. This is a mainstream novel." He thanked me, and he went and picked up a copy of "Dune."

Anderson: The other part of your question, with so many books on whether it's intimidating — what we want people to do is pick up "Dune." That's the first book, and that's the thing. When you read "Dune," you should be inspired to go and read the rest of Frank Herbert's books or read some of our prequels or whatever. The big reward is you read the first one.

This is one of the things that Brian and I did intentionally. There are quite a few "Dune" books, but there's separate trilogies and different timeframes. It's not like Book One through [the rest, where] you have to read them all to get finished. You can read "Dune" and then you could maybe read our Butlerian Jihad trilogy if you want to hear some of the history, or you can read Frank Herbert's own sequel, "Dune Messiah," or we have other different trilogies.

It's a big commitment because they're big books, but it's not like if you read the first one, you have to read all [of them] to get the payoff. Each book should be its own reward.

Herbert: We have 25 published books now.

Anderson: Total?

Herbert: Yeah. Dad didn't write in a vacuum. As I mentioned, he was into mythology, but the sandworms are like the dragon guarding the treasure in "Beowulf." The hero's journey of Paul Atreides hits on 22 points of the classic hero. That's covered in a 1936 book called "The Hero" by Lord Raglan. Even Dad, as original as he was, was inspired by other works, but he was also inspired by the potential for humankind.

The future of Dune

There's a new show in the works called "Dune: The Sisterhood" based on your works. How involved are you in the project, and are there any updates you can provide on that?

Herbert: No, there's been public announcements. Jon Spaihts gave an interview not too long ago, there's been announcements about it, and they did option our novel "Sisterhood of Dune" for the TV series. That's also been announced. We're excited about that project, too.

Outside of "Dune Volume Two," are there any other projects you have in the works you can talk about?

Anderson: "Dune Volume Three." We've already written the script for that. The art takes longer than the script does. Volume Three is in the works from Boom Studios, who is another comic publisher. We just finished doing a 12-issue adaptation of our novel "House Atreides," and we finished the first three scripts of "House Harkonnen," which is the second volume in that trilogy. We will be doing "House Corrino" as a follow-up to that afterward.

Last month, our second story collection came out, called "Sands of Dune." We're still working on it. We're still busy with it.

Herbert: "Sands of Dune" is interesting as Kevin found that we're number one in Amazon for science-fiction and short stories. It's interesting that people want to not only read the novels, but they're interested in the shorter side stories. These are actually novellas, but it's doing well in the short story category.

"Dune: The Graphic Novel, Book 2: Muad'Dib" will be available on August 9. You can pre-order from Abrams Books ahead of time.