The Untold Truth Of William Hurt

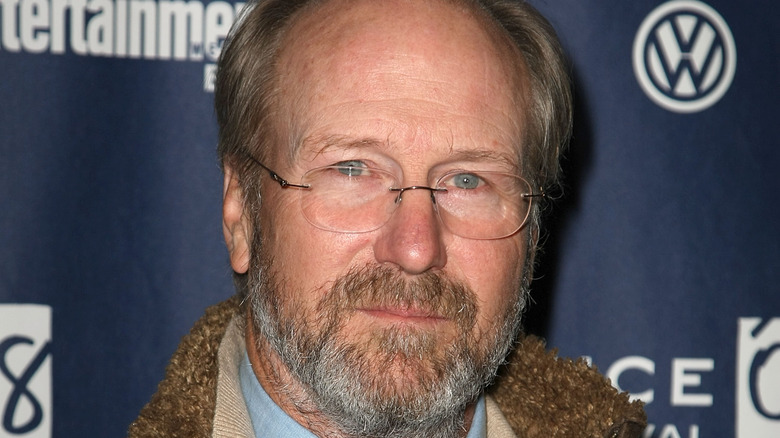

When William Hurt died in early 2022, he left behind a complicated legacy. One of the qualities that put him in such high demand as an actor for multiple decades was his reputation as a tempestuous force, a tall man with a commanding presence that often manifested itself in quiet whispers, seemingly holding a boiling temper back at times.

Off camera, it seems, he might have been very much the same way. As he built a career around iconic turns in films like "Body Heat," "Broadcast News," and "Kiss of the Spider Woman," critics seemed both fascinated and wary of the dichotomy. "He seems thoughtful, wry and funny," critic Janet Maslin once wrote in The New York Times, "yet he has a comfortable physical presence, too, and a friendliness that's uncomplicatedly disarming." As the years went past, troubling details increasingly emerged about past relationships in which he had reportedly become violent.

In a tribute to Hurt after his passing, critic Scout Tafoya wrote on RogerEbert.com that the actor had "left us a terrible burden, as famous men too often do ... On a day we should simply be able to grieve the loss of one of the most distinctive performers in cinema, we must also become reacquainted with the idea that some people knew him only as a monster." From his complicated personal life, to his moving performances, to a transcendent love of acting, here are some facts about William Hurt that you may not know.

He came from a prestigious background

William Hurt's journey towards becoming an actor was not your typical starry-eyed kid finding their big break in Hollywood. Rather, the classically trained actor came from a prestigious New York family.

His parents met in China during diplomatic meetings; his father belonged to the U.S. diplomatic corps, and his mother was an executive for Time Inc. After their divorce, he split his time between them as they traveled, living everywhere from Manhattan to Pakistan, Sudan, Massachusetts, Somaliland, and Greece.

When he was 12, Hurt attended Middlesex private school and began acting. "I played the guy who comes on in 'The Crucible' and says 'The lieutenant governor has arrived,'" he told The Washington Post in 1989. "That was my first line. And apparently in a dress rehearsal — with a full audience — I came on, said the line, then looked out at my director in the audience and said 'Did I do that right?'"

Of course, these inauspicious beginnings did not keep Hurt from success. He went to Tufts, graduate school at Julliard, and then joined the Circle Repertory Company where he won an Obie award for his first leading role.

He preferred theater to film

While Hurt would become most widely known for his film work, his true passion was theater. He acted on stage throughout his career, often returning when he felt like he was becoming disconnected from the craft or over-exposed due to his fame. "Theater taught me I had a love to do something," Hurt told The New York Times in 1981. "It helped me come to a really sincere and integrated notion that acting is acting."

Hurt felt that the stage was where he could find joy in putting forth his very best effort. He appreciated the rehearsal time and opportunity to fully inhabit the character, rare virtues on hurried film and television productions.

"Even one moment onstage is a glacier of comprehension. That's where the work is," he told The New York Times in 1990, while working on a production of Chekhov's "Ivanov." "And it's as fascinating to study as any other science. It's simple and beautiful, not stupid or stupefying. It takes courage to even get up on a stage and stand there."

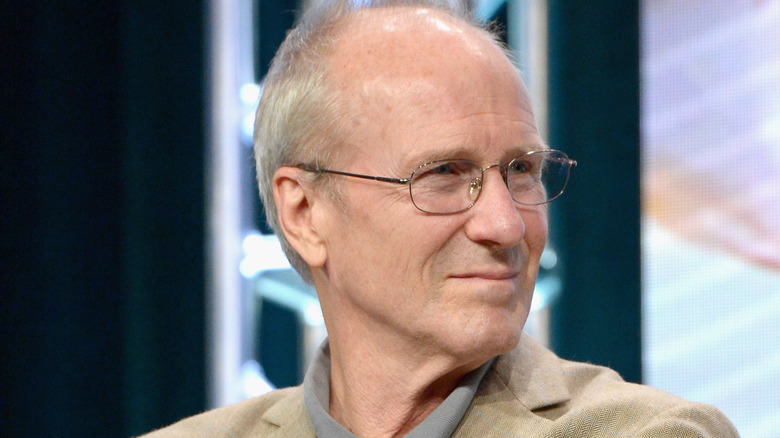

His theology degree made him very philosophical

Before he switched his gaze to acting, William Hurt had been a theology major at Tufts University. This was often noted in interviews with the actor, as Hurt delved into deep topics unprompted. "Elliptical? Philosophical? I can be that way," he admitted to The New York Times in 1994.

Hurt often answered questions about his roles not with facts or anecdotes, but with musings on philosophy and the deeper meaning of acting.

When The Telegraph asked Hurt in 2013 how he chose his roles, he responded, "I choose to go for character. The irony is that the more specific you are in the portrayal of a character, the more like other people you are. In the same way, the more you think about how alone you are in this life, you realize how much a brother and sister everyone else is." Hurt was aware of this habit to wax philosophical, joking to The New York Times in 1981: "The problem is, am I giving philosophy a bad name?"

Later in life, he found that his inward-looking nature stemmed from a love of education. As he told The Telegraph, "The only thing I really want to do these days is go back to school."

He felt his looks kept him from the roles he wanted

William Hurt's tall, chiseled good looks were a huge part of his appeal in roles like "Body Heat" and "Broadcast News." However, Hurt felt early on that his physical appearance tethered him to the limiting notion of being a leading man, keeping him from the more complex roles he truly preferred.

"I'm a character man in a leading man's body," he said to The New York Times in 1981. "I love character roles. I'm trained for them. I have much more fun playing them."

In 2009, Hurt added that when looking back at his career, "I wish I was allowed to basically be the actor that I am, which is a repertory ensemble guy." (via NYT).

As Hurt aged, something unique happened. Rather than clinging to a desire to be the top marquee name, he was all too happy to let leading man roles go to someone else, populating films like "A History of Violence," "Syriana," "The Yellow Handkerchief" and "Vantage Point" with something meatier.

In his mid-40s, Hurt declared that he wasn't "trapped anymore" by those handsome leading man roles. While part of that was due to his maturation, it was also due to his concerted efforts not to be type-cast.

"You have to create a track record of breaking your own mold," he told The New York Times in 1994, "or at least other people's idea of that mold." For the rest of his career, he lived by a new adage: "I want to do what's least expected of me."

He had an intense and lengthy acting process

William Hurt was a theatrically trained actor who valued rehearsal; at times that made him an intense coworker. In 2009, Hurt compared his process to, of all things, the weather.

"Latent humidity doesn't become visible moisture until there's a particulate in the air to which it can attach," he told the New York Times. "So, if there's a fine dust, for instance, in the air, you will have the moment when the latent humidity in the air catalyzes into visible moisture ... I'm not really an artist until I have something to attach myself to. An idea or a concept."

This manifested itself in what many still regard as the apotheosis of Hurt's career, 1985's "Kiss of the Spider Woman." Hurt won his first (and only) Oscar for the role, pushing himself to the point where he was almost unrecognizable. Even his line readings were off the wall, and not everyone appreciated such unmoored exploration.

"His whole shtick consists of the contrary way he plays with the speed and emphasis of his line readings, racing when he should slow down, sliding through the periods in his sentences," critic Paul Attanasio wrote in his review, dismissing the film as "just another gay minstrel show that excuses itself with a pretense of dignity and weighty themes."

Nonetheless, Hurt was never afraid to go wherever such a role would take him — and always seemed most invested in the films that thought highly enough to offer a challenge.

"I'm coming from the notion that acting is an art," he told The Los Angeles Times in 1994. "It is not a business. It is about building characters, not about selling personalities ... I don't owe anybody anything – including the director."

Hurt never directed his own film, preferring to remain on the side of the actor. But if he had, it might have been fascinating to see the results of an artist so singularly focused on defending the process.

"If you don't give me six weeks of rehearsal, I'm going to fight you," he said in 2009. "And so life has been a struggle, I have to say. But it's a good struggle, and every minute of preparation time that I wheedle or gain or coerce or seduce out of a production pays off. Every single second of extra time to work with other actors has definitely always for me paid off for the film. For the project."

He was known as temperamental and difficult

Even as his star soared throughout the '80s, William Hurt gained a not-so-flattering reputation; The New Yorker once called him "notoriously temperamental" and Hurt had little patience for people who didn't respect acting as an art disliking the increasingly commercialized culture of Hollywood.

"Are they A-list, or are they actors?" he commented on many of his contemporaries. "For a lot of them, that's not what I would call acting."

Hurt added: "I try not to give directors the easy stuff. I try to give them the stuff that's true. That's a gift. Some of them don't perceive honesty as generous, and I find that very sad."

Citing an "insane need to inhabit his character," the LA Times once reported that in typical Hurt fashion, he had prepared for the 1994 film "Second Best" by spending multiple weeks with a Welsh farmer during lambing season.

Nevertheless, many directors indulged Hurt; some tried to push him even further.

Director Randa Haines said that for "Children of a Lesser God," one of the all-time great Hurt performances (and another Oscar nomination), she often purposefully provoked him. "It was almost as if that would free him to get to emotions that were not volatile — like some of the sweeter moments or the humor," she explained. "People in the crew thought we were fighting with each other, but we were never in disagreement about the work; it was simply the process, which was difficult for people outside that to understand."

Heywood Gould, director of "Trial By Jury," said that Hurt's passion pushed him to be better. "I think what he does to people is keep them alert and prepared," Gould told The New York Times. "When you know Bill's going to be working that day, you'd better have your stuff together." Director Wayne Wang (who directed Hurt in 1995's stellar indie "Smoke") rejected the idea of him being "difficult" despite his desired rehearsal time eating into Wang's production schedule: "Every actor is difficult in his own way. I respect Bill — he has such incredible passion for his craft."

In the mind of Haines, Hurt's best work came when he was met nose-to-nose, and his lesser efforts often came as the result of being hung out to dry.

"He's had the experience where directors have abandoned him — because they're not sensitive enough or they're tired, or they just don't understand what this person needs, and it's worn Bill into the ground," she explained. "He is a complicated man with a lot of demons. That was very clear when we were filming 'Children'."

He was sued for alimony based on a common-law marriage

In 1989, Hurt received the sort of unwanted attention towards his personal life that he loathed, making headlines as his ex-girlfriend and mother of his child, ballerina Sandra Jennings, sued him for alimony.

The suit was something of a landmark case, because although the pair never married, Jennings and her lawyers argued that the couple had a common-law marriage, entitling Jennings to half of Hurt's earnings since their separation; of course, Hurt's fame (then arguably at its nadir) only made the situation even more high profile. The judge ultimately ruled that the couple had not been married, and Jennings was not entitled to any of Hurt's earnings outside of child support.

While the ruling may have been in Hurt's favor, it didn't stop the emergence of upsetting revelations about the relationship of the couple. Jennings alleged that Hurt would become physically abusive when drunk, while Hurt denied the allegations. Courtroom confrontations resulted in reports of contentious screaming, Jennings' team cited supporting evidence from Hurt's previous relationship with actress Marlee Matlin (who had also alleged that Hurt was abusive — later explained further in her memoir "I'll Scream Later") and Jennings's attorney, Richard Golub, was particularly theatrical in his attempts to rile up Hurt and other witnesses (via Los Angeles Times).

At one point, Golub claimed that the judge had only ruled in Hurt's favor because she had fallen in love with the actor; Hurt's younger brother Jim Hurt told People for a 1989 cover story that the whole thing was "a tragedy." After Hurt's passing in 2022, Golub penned a Daily Beast article in which he accused the actor of lunging at him in anger during their first encounter: "That was a sample of what Hurt was capable of, and he should have been locked up on the spot."

If you or someone you know is dealing with domestic abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

He suffered from addiction

Another unflattering detail to emerge from Hurt's very public alimony trial was his acrimonious behavior when drinking. "He'd have one drink and he'd have a personality change," Jennings testified. "When he didn't drink for a couple of days, he'd get violent."

During the trial, Hurt's publicist Lois Smith shared that the actor had placed himself in the Betty Ford Rehabilitation Clinic in 1986, and attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. While Hurt never commented on his struggle with addiction during the trial, his longtime friend and "The Big Chill" co-star Glenn Close told People: "The important thing is that Bill is really doing something about it. He's seeking support, and he's passionate about it, and for that reason he has my deepest respect."

Hurt would soon publicly acknowledge his struggle with addiction. In a 1989 interview with The Washington Post, he said "I'm an alcoholic — a recovering alcoholic. I'm finally admitting that I needed help with that. I'm finally admitting what it was — which is a disease, like diabetes or cancer. And accepting that has meant the difference between a happy and an unhappy life. The most important day in my life was the day I asked for help."

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

He disliked fame and wanted privacy

Hurt was clear that he felt privileged to be able to act for a living, often calling it "a gift" (via The Washington Post). However, there was a downside to his success that he never seemed to get past: fame. Hurt intensely valued his personal life, and felt that his fame invited people to violate it.

"It's not right that my privacy is invaded to the extent that it is," he told The New York Times in 1989. "I'm a very private man, and I have the right to be. I never said that because I was an actor you can have my privacy, you can steal my soul. You can't."

Hurt's discomfort with fame was a contributing factor in his struggles with addiction. His brother Jim told People in 1989 that "Bill is a very good guy, but his fame has made him paranoid over questions of control," noting that Hurt's drinking worsened after his role in 1980's "Altered States," the film that first made him a star.

Looking back on his experiences in 1994, Hurt admitted he had struggled mightily at times. "Fame... it's been a challenge, let's put it that way," he told The Los Angeles Times. "It's a privilege and a responsibility, and I'm not sure I carried the responsibility well at times, which is embarrassing. And I've had to look and be disappointed in myself occasionally for how I behaved in some circumstances."

He was essentially ousted from Hollywood for many years

During the 1980s, William Hurt was one of Hollywood's go-to leading men. By the 1990's, he was conspicuously absent from movie screens for much of the decade.

Following his bravura turn in 1988's Oscar nominated "The Accidental Tourist," Hurt's career became an underwhelming panoply of forgotten studio treacle ("I Love You to Death," "Mr. Wonderful"), underseen auteur efforts (Wim Wenders' "Until the End of the World," Woody Allen's "Alice," Wang's "Smoke") and films that barely got a theatrical release ("Second Best," "Secrets Shared with a Stranger"). It wouldn't be until the latter half of the '90s that Hurt would reinvent himself as a character actor, turning in solid supporting work in the John Travolta vehicle "Michael" and the masterful Alex Proyas sci-fi film "Dark City."

"He has no draw whatsoever," a senior executive at a major studio anonymously told The Los Angeles Times in 1994. "[Hurt's] name means nothing right now to studio people."

Hurt would claim that his receding fame during this period, as well as the unique choices in roles he did accept, was related to his dislike of Hollywood, which he felt had become more focused on selling the idea of a person rather than the art of creating characters.

"Being 'well-received' is not what I want," he told the LA Times. "If a director tells me to make the audience think or feel a certain thing, I am instantaneously in revolt." Hurt added that there was another reason for his absence: his unwillingness to go out to the west coast. "I pretty much don't get on the plane," he told The New York Times in the mid '90s.

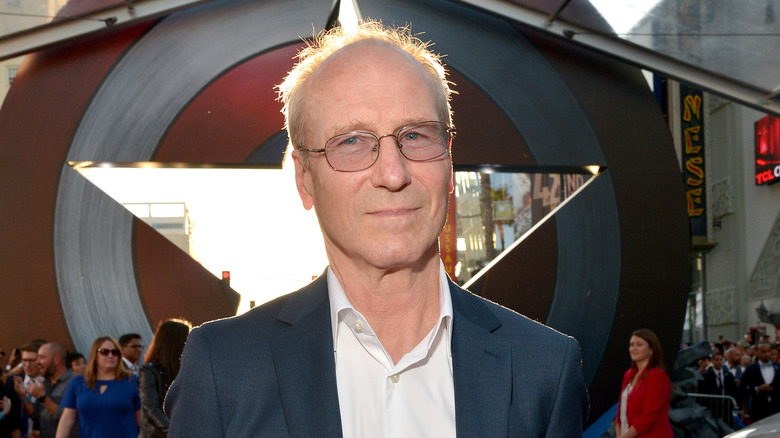

Details surrounding his death

In 2022, at age 71, Hurt passed away at his home in Portland, Oregon, after battling prostate cancer for several years.

He had experienced a significant renaissance as a character actor — which was what he always wanted to be — in late career films like "The Village," "A.I.: Artificial Intelligence," and "A History of Violence," for which he scored his last of four Oscar nominations. He also came to be a key player in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, bridging an unlikely gap between its early days and 2020's dominance by appearing as General Thaddeus "Thunderbolt" Ross in five films over 13 years ("The Incredible Hulk," "Captain America: Civil War," "Avengers: Infinity War," "Avengers: Endgame," and "Black Widow").

Hurt's son, actor Alexander Hurt, told The New York Times upon his passing that he will always remember his father for "the pride he took in the work he did ... he had a pure spirit, and that's what we're all going to miss the most, and the way he challenged us all."

In an official statement, Hurt's family wrote: "The world knew him as an incredible artistic force, a vessel for his many characters, a shapeshifter with an unbending willingness to seek out truth in story, a hunger to peel back what has been forgotten in our humanity, and a passion for the ways that art can validate our living experiences ... His children and his grandchildren will remember him for his vibrant curiosity, for his storytelling, his playfulness, his wildness, his unmatched sense of light and dark both, and his sea-crashing love."

Acting was his great passion

In a viral Twitter thread, writer/film critic Sheila O'Malley shared the touching story of when she was a young, struggling actor in Chicago. During a run of the fledgling play "Golden Boy," one of O'Malley's costars wrote a letter to William Hurt, pleading with him to come. Hurt, known for his deep love of theater, actually did show up — but that night, no one else did.

O'Malley and her fellow actors performed the entire play that night, with only William Hurt in attendance; when the lights came up, the actor was in tears. "That was one of the most profound theatrical experiences I've ever had," O'Malley recalled. "I can't put it into words."

Acting was Hurt's great passion, and putting everything into the craft seemed to be one of the few healthy outlets he had at certain times in his life.

"It's as if someone forgot to tell him that he won an Oscar: he seems to think he still has everything to prove," the New York Times said in a 1994 profile. "He is most animated when talking about acting, paying compliments to Meryl Streep ... Gary Oldman and his former Juilliard classmate Mandy Patinkin. At one point he grabs a visitor's glass of water to act out the concept of objectives and obstacles. Later he makes an example of a throw pillow on the sofa, analyzing the difficulty of touching it 'without making something out of it, but just to experience that'."

"It is very good that an actor feels such responsibility as a human being, not just as an actor," Russian director Oleg Yefremov (who oversaw Hurt in a 1990 production of Anton Chekhov's "Ivanov") said of the actor at the time. "That will come through his performance and touch a lot of people's hearts."

"I don't want my children to have to wade through the crap to get to the cream," he said of his own approach to the impressive filmography he would leave behind. "I want them to be aware that I struggled to live with and tell my truth, and that it was a decent thing."