Things Only Adults Notice In Spirit

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

"Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron" might be north of twenty years old, but every frame continues to impresses. A throwback to the glory days of beautiful, hand-drawn animation, "Spirit" would become a forgotten gem among the increasingly CGI-heavy kids entertainment that came to dominate post "Toy Story." In the years since, audiences have been deluged with chattering anthropomorphized animals, gibbering Minions, and endless variations of the smug expression known as "Dreamworks face" — yet, one of Dreamworks' earliest movies remains a breath of fresh, naturalistic air.

"Spirit" unfolds in 1800's America, against the backdrop of the newly-formed nation's bloody expansion westward. Despite the tragic implications around the edges of its story, "Spirit" holds up as a self-contained story about perseverance, one worth revisiting for what it is and what it isn't compared to many other more frenzied childhood relics. It is modest in its ambitions, yet grandiose and majestic in its execution. These are the things only adults notice in "Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron."

The miracle of life

Countless Disney movies involve parents: dead parents, missing parents, long-lost parents, fairy god-parents, and so on. "Spirit" gets right to its audience, depicting the miracle of life firsthand in the birth of the Mustang stallion Spirit.

His mother neighs painfully in a meadow for several moments, and eventually a baby Spirit slides out, tastefully obscured to some degree by the tall grass. It is presented without comment, and almost documentary-like in its realism, where most cartoons would probably cut from a pregnant mother to an adorable animal child and not take the risks of such an educational, literal approach.

Granted, Spirit probably comes out a lot less gooey in the movie than a foal would in real life; he also learns to walk in mere seconds, compared to the (nonetheless pretty impressive) two hours it takes a real baby horse to start walking. But the entire sequence, which even shows a shot of Spirit's vision of the world coming into focus for the first time from his perspective, is a profound sequence that isn't replicated in many other kids movies. Hans Zimmer's score mirrors Spirit's delight as he discovers what it's like to be alive, and exist in the beautiful, natural world. With a simple opening sequence, "Spirit" announces its intention to tell a story with a deep zeal for life.

Spirit makes you resent Shrek

Animated movies take years to make, so perhaps it's a bit unfair to pit two movies from the same studio against one another. But when you look at the numbers, it's impossible not ponder "Spirit" making $122 million on an $80 million budget and "Shrek" making $484 million on a $60 million budget, only a year apart. In the decades since, it's no wonder that Dreamworks chose to drown moviegoers in "Shrek" sequels and other CGI franchises like "Kung Fu Panda" and "Madagascar."

Even with occasional outliers like the "How to Train Your Dragon" movies, it's clear that in a broad sense Dreamworks took to heart that early '00s lesson that overstuffed, pop-culture referencing, celebrity voice-powered CGI was more profitable than quiet, thoughtful original films like "Spirit."

Twenty years later, the hand-made attention to detail of films like "Spirit" and "Prince of Egypt" has been left in the dust for screen-saver quality CGI of films like "Puss in Boots" and "Shark Tale." Are movie lovers any better off? In some alternate universe, one without "Shrek," Dreamworks focused on unique, well-told stories instead of becoming the dime-store version of Pixar.

The film is almost meditatively wordless

Of all the bold choices in "Spirit," the one that stands out most is not having any of the animals in the movie talk. While they make the occasional human-like facial expression, and Matt Damon pipes up every now and then as the voice of Spirit narrating the story to us, the audience, there's no animal-to-animal dialogue, as is so common in animated animal films. At first, it might be a frustrating watch, because you're so accustomed to dialogue being the primary driving force of a story.

But as "Spirit" moves along, the lack of dialogue Allows the film to set its own pace, one that's quiet, patient, and largely wordless. The film opens with an eagle soaring majestically over the landscape, and after a brief voice-over, Spirit grows to adulthood in a montage that doesn't call for words in the first place. By the end, the unconventional quiet of "Spirit" has provided more mindfulness during its runtime than a month of meditation apps could ever hope to achieve.

Reckoning with our country's past

For some time, the teaching of American history to school children has been a hot-button issue, one often being rightfully re-examined. "Spirit" offers a refreshingly clear-eyed look at the period known as the American Frontier Wars, when the United States Cavalry had periodic armed conflicts with various tribes in between brief, treaty-based times of peace. Simply put: We're the bad guys, and "Spirit" neither hides from this reality nor lingers on it.

When Spirit is first captured, he's taken to a U.S. Cavalry fort; it is clear that the soldiers attempting to "break" him and get him to accept a rider are the villains, particularly the stern, malevolent Colonel (voiced by James Cromwell). When Little Creek, a member of the Lakota, is similarly imprisoned and helps break Spirit free, he and the mare Rain show Spirit a much more benign, symbiotic relationship between man and horse — at least, until the U.S. Cavalry return and raid a peaceful Lakota camp full of women and children.

"Spirit" keeps any major violence off-screen, but the terror inflicted by U.S. forces is very real, and Spirit's eventual use as a pack horse to help build the railroads serves as a subtle but distinct indictment of ceaseless American capitalism.

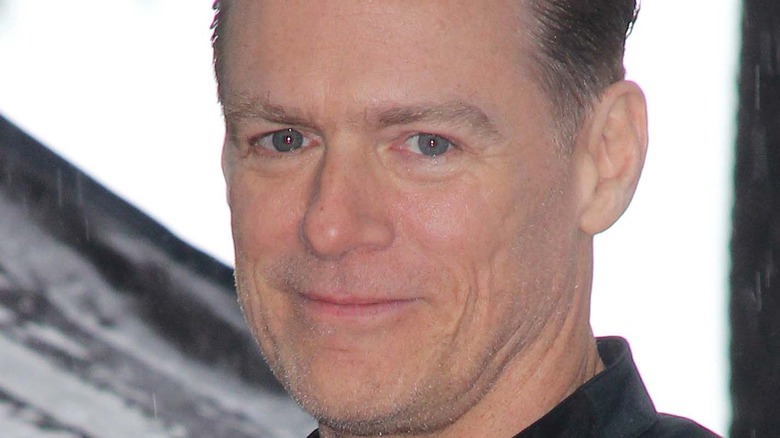

Your Bryan Adams mileage may vary

For a film that's otherwise a timeless story set more than a century ago, the most 2002 thing about "Spirit" are several songs by rocker Bryan Adams. They're fine, if you happen to be a Bryan Adams fan, but can feel jarring every time they intrude over the mostly wordless, contemplative movie.

The compositions from the "Summer of '69" singer are all original songs clearly written to coincide with the themes of the story; "Here I Am" and "I Will Always Return" are about Spirit's love for his home and his pride, for instance.

It's a rare concession to the 1990s Disney movies that were often fueled by high-profile soundtracks anchored around the likes of Elton John and Phil Collins. "Spirit" at times feels like it's trying to have things both ways, with Bryan Adams charting Spirit's emotional journey in song. But the way the songs non-dietetically intrude over montages never really adds much.

The audience knows Spirit doesn't want to accept a rider, for instance, because scenes have shown the horse throwing a bunch of people off when they try to ride him; Adams singing "Get Off My Back" is just over-produced overkill. In a movie fueled by a "show, don't tell" mindset, the soundtrack ruins the mood by doing the opposite.

How does no one notice horses are sentient?

With virtually no dialogue, "Spirit" does make a concession to the tradition of kid movie animals by giving Spirit and his fellow horses dynamic, expressive faces that display very human-like emotions. They glare in anger, they go wide-eyed in delight, and at the end of the movie Spirit and arch-enemy the Colonel even trade apparent nods of respect.

There are several instances in "Spirit," however, when horses act so human-like that you wonder why their riders don't pick up on the horses having apparently gained sentience.

Everything about the horse behavior on display when Spirit is captured by the Cavalry is both self-aware and a bit creepy: Spirit's commitment to not accepting a ride, the Cavalry's horses laughing aloud every time he throws a rider, Spirit pretending to faint in exhaustion. In some ways, it feels like the horses are smarter than the humans.

Spirit is more beautiful than most kids movies

As an adult, there might not be many things that truly take your breath away. But "Spirit" harkens back to an era where every frame of an animated movie was a painting in itself, containing gasp-inducing moments that hit adult viewers differently.

The visuals range in scope from the stunning plains of the Cimarron as an eagle flies above them to the small detail of Spirit's image refracted through an icicle in an early scene. At night, the silhouettes of a team of horses are seen in brief glimpses, illuminated by a pattern of lightning in the sky. Spirit sees a vision of his family in the swirling snow, then later runs from a tumbling railroad engine and narrowly escapes a fiery inferno that puts many live action sequences to shame.

Even for a hand-drawn film (for the record, the film uses a combination of hand drawn and CGI methods), "Spirit" focuses on the composition of its visuals in a way that's pause-worthier than many of its contemporaries.

The sad future of America's wild horses

"Spirit" has the happy ending you might predict, but growing up and knowing the general direction of America's relationship with nature, it's hard to not think about the dwindling number of wild horses in the landscape of America, worrying perhaps for the future of Spirit and his pride.

Just like the Lakota, the subtext of Manifest Destiny makes you fret for the ultimate fate of Little Creek, and know for a certainty that the railroad will overcome Spirit's sabotage and likely be built through his home plains at some point, likely not too long after the credits.

While there are plenty of kid-targeting movies with depressing subtext ("The Land Before Time" might make adults think about meteors, for example), by mining the relatively recent past, "Spirit" touches a nerve buried directly in between the bowdlerized, cheerful idea of America taught to school children and a more complicated, distressing reality.

Why is the Colonel so obsessed with Spirit?

Every good kids movie needs a requisite evil villain, and the Colonel fits the bill in "Spirit." He is determined to make Spirit fall into line, to the point where he's perhaps unhealthily obsessed with the heroic horse.

At first, he seems to take only a passing interest in how difficult it is becoming to "break" the wild stallion his men have acquired, but he eventually resorts to starving Spirit for three days just to break the horse's will. He drinks water in front of a desperately thirsty Spirit to taunt him, makes absurd speeches about how Spirit represents the American West itself, and engages in other such theatrics.

Calm down, dude; it's just a horse. During the climactic end sequence of the film, the Colonel leads other soldiers on a ridiculously dangerous pursuit of Spirit high up into the mountains, stopping only when the horse makes an Evil Knievel-esque jump across a huge chasm. At this point, the Colonel nods to Spirit, having somehow turned his glassy-eyed hatred into respect.

Other than being a stand-in for the faceless imperialism of the U.S. Military, its not explained what drives the Colonel to be such a hardliner; in another life, perhaps, he could have been friends with Spirit with a friendlier approach, like Little Creek.

All Spirit does is get captured

The most glaring thing "Spirit" lacks is much of a plot. After taking its sweet time establishing any sort of stakes or conflict, Spirit's story becomes getting captured shortly after having just escaped capture.

First, he's caught by some travelers that bring him to the Cavalry, then by the (admittedly much nicer) Lakota, and then once again he's caught by the Cavalry and sent to work on the railroad. By the time he escapes for the fourth time, you can't imagine the foolhardy Mustang staying free for all that long, ever.

This aimless waltz in and out of captivity covers for probably the only general weakness of the movie, especially from an adult analytical lens: Spirit doesn't really learn anything or grow as a character. Other than "don't investigate strange campfires," there's not really a lesson to the movie. Spirit also doesn't face many consequences for his foolhardiness in the end, falling in love along the way and returning home with a mate. Even well-placed Bryan Adams songs can't stand in for character development when it isn't there.

How did Spirit launch an entire franchise?

You might remember "Spirit" as a one and done story; stealthily, however, it has become nearly as prodigious as "Shrek."

Since 2002, "Spirit" has begat a sequel movie, as well as four animated series and two TV specials. It did take a gap of 15 years, however, for "Spirit" to be expanded, with the spinoff series "Spirit Riding Free" debuting in 2017.

The series focused on Spirit's son, conveniently named Spirit Jr. for the sake of continuity. Produced by Netflix and Dreamworks Animation together, it ran for eight short seasons, and has spun off into side series, specials, and the 2021 movie "Spirit Untamed." In large part, the sequels all focus on children that befriend Spirit Jr. and other horses, and they tend to have to save them from nefarious horse wranglers, sparing the "Spirit" franchise from further interrogating the questions the original movie raised about the U.S. Cavalry's role and the ongoing creep of industrialization. What was once a realistic, neutral depiction of 1800s America has been spun off into something more like a fairy tale after all.