The Untold Truth Of Pixar

For over two decades, the Pixar name has been synonymous with heartfelt, hilarious, high-quality entertainment. The studio boasts an astonishing ten theatrical features that sport a Rotten Tomatoes rating higher than 95%, and they've earned a stunning eight Academy Awards for Best Animated Feature along the way. Yet as tough as it might be to imagine now, before they wowed critics and audiences with 1995's Toy Story, nobody was quite sure if a computer-animated feature film was even viable.

The idea that launched the studio was actually born more than two decades earlier, far away from Hollywood, and its originators are responsible for a great deal of what we see onscreen today, from whimsical cooking rodents and talking toys to the modern, computer-enhanced special effects that populate every big blockbuster. To box-office infinity—and beyond!—this is the untold truth of Pixar.

It started at the New York Institute of Technology

In the early 1970s, computers were only capable of producing the most primitive 2-D graphics, but one man was convinced they were capable of much more. Dr. Alexander Schure had an insane dream to create a full-length film using computers, and while he didn't have a great deal of technical know-how, he did have a lot of money. In 1974, Dr. Schure established the Computer Graphics Lab at the New York Institute of Technology, and over the next decade or so, he'd dump untold funds into the lab in pursuit of making his dream a reality.

In charge was a young programmer named Ed Catmull, the future president of Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios. With virtually unlimited funding, no set goals, and a mandate simply to push the technology as far as possible, the breakthroughs came early and often. Another of the Lab's programmers, Alvy Ray Smith (who would go on to co-found Pixar with Catmull) later remembered, "None of us slept... everything you saw was something new. We blasted computer graphics into the world. It was like exploring a new continent."

The clip above is a sort of culmination of the Lab's work, aptly titled The Works, which was labored over from 1979 to 1986. By this time, many of the animators could see the dream of a full-length CGI feature drawing closer—but first, they had to get to Hollywood.

The Lucasfilm years

The Lab got its Hollywood break when Catmull—now Dr. Catmull—was hired by Lucasfilm to head up the Graphics Group, which constituted one-third of the studio's computer division. Roughly 20 members of his NYIT team followed—slowly, over the course of a year, so as not to arouse Schure's suspicion—and they started work on a key project: "Motion Doctor" (which would eventually become "RenderMan," still a vital computer animation tool), an interface that would allow traditional cel-based animators to easily render computer-animated images with little training. The team also started working with the outfit that would become special effects house Industrial Light and Magic, and together they applied their technology to film, using early CGI for scenes in 1982's Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and 1985's Young Sherlock Holmes.

The group's custom hardware caught the attention of Steve Jobs, who by 1985 had parted ways with Apple Computer, the eventual tech titan he'd co-founded. In 1986, Jobs made a $10 million investment enabling Pixar to buy its way out of its relationship with Lucasfilm, and the newly christened Pixar Inc. became its own entity for the first time, with Jobs holding 70 percent ownership and the employees holding the rest. Jobs' involvement meant Pixar's Hollywood dreams were put on hold—but a key piece of that puzzle was taking shape in the form of a young Disney animator who had some big dreams of his own.

John Lasseter started with Disney

In 1983, Disney's in-house newsletter published an article entitled "Experimenting with Computer Generated Graphics." It highlighted the work of two of its young animators, Glen Keane and John Lasseter, whose big project was a 30-second test reel based on the children's book Where the Wild Things Are combining hand-drawn animation with a computer-rendered 3D environment. The idea was to use the technique for an adaptation of another children's book, The Brave Little Toaster, and Lasseter crossed paths with his future colleagues for the first time when he suggested Lucasfilm as a possible choice to do the CGI work on the project. Catmull was blown away by the test reel, but—not being in a position to contract out the services of Lucasfilm—had to pass.

Unfortunately, Disney head Ron Miller wasn't keen on any process that wouldn't make animation faster or cheaper. After formally pitching Brave Little Toaster to Miller, Lasseter was shocked to receive an ice-cold reception—and even more shocked when animation department manager Ed Hansen called him into his office shortly afterwards to let him know he was being fired. Months later, Lasseter and Catmull would bump into each other at a computer graphics conference, and the rest is history—but first, the company would have to undergo a slight change in direction.

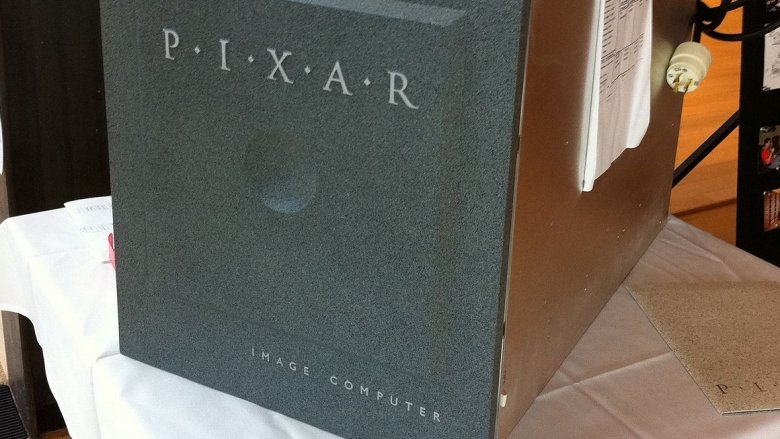

Their first business was hardware

For the next several years, newly-independent Pixar's animation department would be an afterthought. The company's main focus was its hardware, the Pixar Image Computer, a high-end imaging machine that Jobs thought could become standard equipment in medicine, engineering and science. With a price tag of $135,000, wide adoption could have propelled Pixar into the stratosphere as a hardware company—but only about 120 of the machines were ever sold.

During the Image Computer's time on the market, the animation department was mainly tasked with producing short animated films to show off its capabilities. The first of these films, produced by Lasseter, debuted at a 1986 computer graphics conference and astonished everyone in attendance. Luxo, Jr. is the simple story of a lamp named Luxo teaching his son to play with a ball, but the graphical horsepower on display was simply unprecedented. From its use of light and shadow to the incredibly lifelike movements of its subjects, nothing like it had ever been seen before, and it made enough waves to earn an Oscar nomination in 1987 for Best Animated Short Film—the first CGI short to receive the honor.

This led to plenty of work for Lasseter and his team producing commercials for clients like Tropicana and Lifesavers, but the Image Computer's non-existent sales threatened to drag down the entire company. The hardware division was sold in 1990 (to a company that went bankrupt a year later), and Pixar's animation department was on its own.

Disney to the rescue

Even during the hardware years, Pixar's animators never forgot their dream of making a feature film. Fortunately, one of the few takers on the Image Computer during its run was Disney; in 1990, the studio started discussions with Pixar's management to produce a movie, and a deal materialized for not one but three computer-animated features. It seemed like a dream come true, but the initial deal was a bit lopsided. While Disney would reimburse Pixar's production costs, it would keep nearly everything else, including the lion's share of profits and the rights to the characters.

After the success of Toy Story, Pixar was able to renegotiate, and in 1997 a new five-picture deal was announced in which the costs and profits would be split equally between the two companies, with Disney also receiving a distribution fee. Under this more equitable arrangement, Pixar would produce five classics—A Bug's Life, Monsters, Inc., Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, and Cars. As the agreement neared its completion in 2004, Pixar announced that talks to renew the agreement had fallen apart—behind the scenes, Jobs and Disney CEO Michael Eisner had a contentious working relationship, and Jobs still wasn't happy with Pixar's cut. But Eisner was ousted in 2005, and new CEO Robert Iger was instrumental in paving the way for Disney's $7.4 billion acquisition of Pixar in 2006.

Toy Story was nearly canceled

Toy Story's massive success built the ship that would soon set sail on vast oceans of cash, but it almost wasn't to be—in fact, the first footage produced for the project made Disney executives so angry, they very nearly canceled the film and fired all of Pixar's animators on the spot. Only a last-minute appeal from Lasseter, who was given two weeks to right the ship, spared the film from the trash bin and the animators from the unemployment line—and ironically, it was largely the Disney chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg's influence on the script that caused problems.

Katzenberg had insisted on a tone more consistent with the edgy cartoons that were popular at the time, meant to appeal to adults more than kids. As a result, Toy Story was shaping up to be much less lighthearted and far darker than Lasseter's team would have liked. Tom Hanks, who by this point had already been cast as Woody, thought the character seemed like kind of a jerk, and Katzenberg even had to agree that he'd been wrong. Amazingly, the team was able to use their two weeks to completely rework the script to everyone's satisfaction, and the project was spared. It started an impressive streak, too: in their entire history, Pixar has only had one original production get the axe—Newt, which was announced in 2008 but canceled in 2010 due to multiple competing studios developing similar projects (one of which was Dreamworks' Rio).

Disney almost made several Pixar sequels on their own

When the agreement between Pixar and Disney ended in 2004, both companies asserted that they didn't need each other. Jobs felt a 50/50 split was still too much, and thought Pixar could do better on their own—and as for Disney, who owned the rights to the characters created under the deal, Eisner simply intended to go ahead with sequels without Pixar's involvement. In 2005, Disney established Circle 7 Animation to produce a slate of sequels to Pixar's classics. First up was Toy Story 3, which would have been released in 2008 with a completely different story from the version we eventually got. Monsters Inc. 2 also got a production team and went as far as the concept art stage, and a screenplay was drafted for a sequel to Finding Nemo.

All of these projects were abruptly canceled when Disney's acquisition of Pixar was announced, and Circle 7 was shut down shortly afterward. Disney Animation Studios would exist alongside but completely separate from Pixar for years—to maintain quality, the heads of both studios implemented a hard and fast rule that they were not to share ideas, animators, resources, or literally anything else. It wasn't until nearly a decade later that each studio's brain trusts were allowed input on the other's work—Disney's creative team offered some advice on Inside Out, while Pixar's was able to spot a couple of snags that were gumming up Zootopia.

Each movie has an accompanying short

Pixar's heart has always been in its short films, as evidenced by the fact that the clumsy lamp from "Luxo, Jr." became the company mascot, appearing in their logo from Toy Story on. The groundbreaking "Tin Toy," released in 1988, furthered the company's early reputation for shorts packed with story and nuanced characterization, but unless you happened to catch all of Pixar's films in the theater, you may not know that this legacy continues to this day. Starting with their second feature, A Bug's Life, every Pixar movie to hit theaters has had a short film specially produced to accompany it.

It's for a good reason that this tradition continues. Like they've done since the '80s, Pixar uses their short films as testing grounds for new technologies and techniques—and also for up-and-coming animators. Pixar shorts have won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film no fewer than four times amidst a slew of nominations and too many film festival awards to count; additionally, Luxo, Jr. and Tin Toy were both selected for addition to the National Film Registry for their cultural and historic significance.

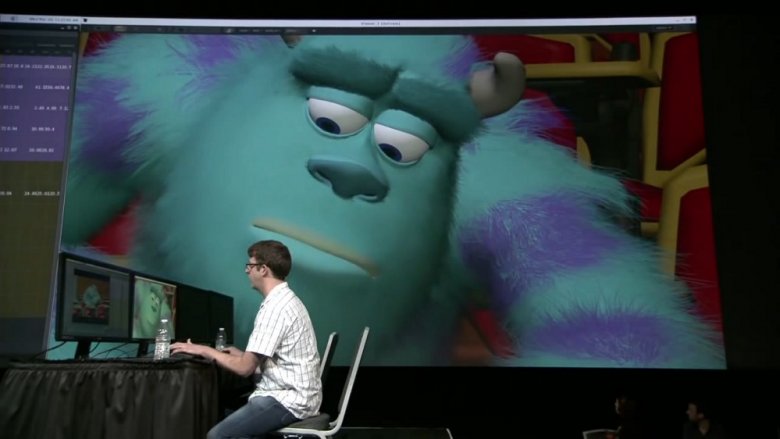

They have their own animation software

Since its internal debut in 1988, the previously mentioned RenderMan ("rendering" is the process of converting 3-D wireframe models to 2-D images on a screen) has gone on to become extremely popular in the computer animation industry—it's been commercially available for years, and as of 2015 is even free to use. But the heart and soul of Pixar's process is its proprietary modeling software, which also came online in 1988 under the name "Marionette." The two applications were used in conjunction for the first time on Tin Toy, and while animators the world over may sing the praises of RenderMan, there's only one way to get hands-on experience with that proprietary modeling suite: get a job at Pixar.

The software has since been completely rewritten and renamed "Presto," after Pixar's Oscar-nominated short film of the same name, which was released in theaters alongside WALL-E. The revamped suite first saw action in 2012's Brave, has been used to animate every Pixar film since, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. A rare public demonstration took place at a 2014 technology conference; for those who are extra-curious about how Pixar's animators work their magic, the entire presentation can be viewed online.

Pixar are really fond of tradition

Pixar is a company with a strong sense of tradition that leans toward the downright sentimental, and the proof is in each of their films. The animators are fond of packing their labors of love with inside jokes and Easter eggs for audiences to find, among the most obvious being the number "A-113"—a reference to the number of the animation classroom at the California Institute of Arts—which appears somewhere in nearly every Pixar movie, and a Pizza Planet truck that appeared in Toy Story and then just kept showing up time and again. The filmmakers also liberally sprinkle their works with references to other Pixar films of the past, such as Riley from Inside Out appearing among a group of kids at the aquarium in Finding Dory, and even of the future—such as Doug the dog from Up (2008) making an appearance in Ratatouille (2007).

Aside from such Easter eggs, you can count on exactly one thing appearing in every Pixar film: John Ratzenberger. Best known for his role as Cliff in the '80s sitcom Cheers, the beloved character actor has voiced a role in every single feature the studio has ever made—a fact that the end credits sequence of Cars couldn't help having a little fun with.