What These Movies Really Look Like Before Special Effects Are Added

We're currently going though a period in movie history that will be remembered as the time when CGI started to seamlessly blend with live action. Hollywood blockbusters have become increasingly reliant on visual effects over the past few decades, but recent advances in technology have made it so feats in VFX work that were considered impossible just a few years ago are well within reach.

As the scope of what can be achieved with computer-generated imagery widens, the more studios are tempted to use it—not just out of necessity, but simply because it's often cheaper than the alternative. In fact, many modern blockbusters are covered in so many digital layers that the original footage looks unrecognizable—and more often than not, completely ridiculous. Here's what these movies really looked like before special effects were added.

300: Rise of an Empire (2014)

Set before, during and after the events of the first movie, 300: Rise of an Empire lacked Zack Snyder's "shrewd deconstruction" of Frank Miller's graphic novel as well as the "staunch physical presence" of Gerard Butler in the lead role. Butler famously got super-jacked for 300 using an insane workout, though CGI was still needed to bring the world around him to life, and the technology used to create it had advanced immensely by the time Rise of an Empire came about.

"It's amazing how the tools available eight years later continue to develop," director Noam Murro told Forbes. "A major difference is CGI and the ability to create things in post that are convincing and complex and three-dimensional. The idea of creating a water movie without a drop of water on the set is remarkable." The filmmaker also revealed they relied on some of the same techniques used in the Oscar-winning CGI blockbuster Gravity.

Elysium (2013)

Neill Blomkamp's follow-up to his acclaimed debut District 9 didn't exactly go as planned, despite the star power of Matt Damon. The blockbuster sci-fi cost a whopping $110 million to make, but only returned $93 million at the domestic box office. Blomkamp took full responsibility for the film's failings, telling Uproxx that he "****ed up" the script. "I feel like, ultimately, the story is not the right story," he said. "I almost want to go back and do it correctly... I just didn't make a good enough film is ultimately what it is."

The South African director didn't have any complaints about the special effects team, however, who were expertly led by his trusted collaborator Peter Muyzers. "Having worked with Neill before, we were able to prepare well in advance for Elysium and really get things into place," Muyzers told Collider. "So the real challenges on that film were just the variety of character work ... There were about three times as many shots in Elysium as there were in District 9 from a visual effects point of view."

Jurassic World (2015)

When Steven Spielberg decided to adapt Michael Crichton's novel Jurassic Park, CGI as we know it today didn't really exist. Universal assembled the top visual effects talent in the business for the project, but despite Spielberg's kids being impressed with early tests done using stop-motion technology, the veteran director wasn't quite satisfied. Industrial Light and Magic (who at this point had done little more than render liquid metal in Terminator 2) were tasked with creating living, breathing dinosaurs using computer-generated graphics, and their efforts proved revolutionary.

Of course, it wasn't just CGI that brought the inhabitants of Jurassic Park to life. There were a number of practical effects used too, and ILM mixed it up in the same way for Jurassic World. The fourth film in the franchise used detailed white casts of dinosaur heads that would later be layered with CGI for close-up shots, and they used actors in motion capture suits to make sure their movement seemed real. "It gave us a new natural look for the animation," VFX supervisor Tim Alexander told Below the Line. "We ended up casting a person to give us a consistency in the performance. There were individual people being that raptor. We had suits that they would put on with a tail."

Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

When George Miller returned to the world of Mad Max with his critically acclaimed tour de force Fury Road in 2015, audiences were blown away by the sequel's frenetic pace and visceral action—much of which was achieved through the hard work of inventive mechanics who built the weird and wonderful vehicles used in the movie from scratch. "Mad Max was always about cars," production designer Colin Gibson said. "The cars were a metaphor for power, and the one thing that George was very keen on and understood, I think, was that in a world where there's next to nothing, what little there is left needs to be loved."

The chase scenes were all shot for real, but the final product wouldn't have looked anywhere near as eye-popping if it weren't for the VFX team. Led by supervisor Andrew Jackson, hundreds of CGI artists enhanced over 2000 shots in Fury Road, from adding characters to creating an epic toxic storm. "We sourced a huge amount of real twister footage to find visceral effects we liked and thought would work well for this sequence," CGI artist Tom Wood told IndieWire about creating the movie's biggest VFX scene. "Lightning strikes were added as light sources, casting shadows onto and lighting through the dust layers."

The Avengers (2012)

When Earth's Mightiest Heroes teamed up on the big screen in 2012, the stakes were high for Marvel Studios and their team of visual effects artists. "With Avengers, there were so many things to get right," Jeff White, the film's VFX supervisor, told MTV. "We created a lot of New York City for the film and needed to build flying shots of Iron Man all from photography. We had to build a new Iron Man suit—the Mark VII—and Stark Tower. We had to build the alien race. When you add all of those things up, there are quite a few challenges there."

Green screens were used during most of the film's action sequences, so the cast spent a good chunk of time reacting to invisible threats and taking cover from fake explosions. The biggest hurdle they faced was inserting the Hulk (Mark Ruffalo) into group situations. "We wanted it to feel very natural when he's sitting in that circle of Avengers," White said. "We spent a lot of time working on his skin and his hair and his teeth, just to make sure that all of that was believable."

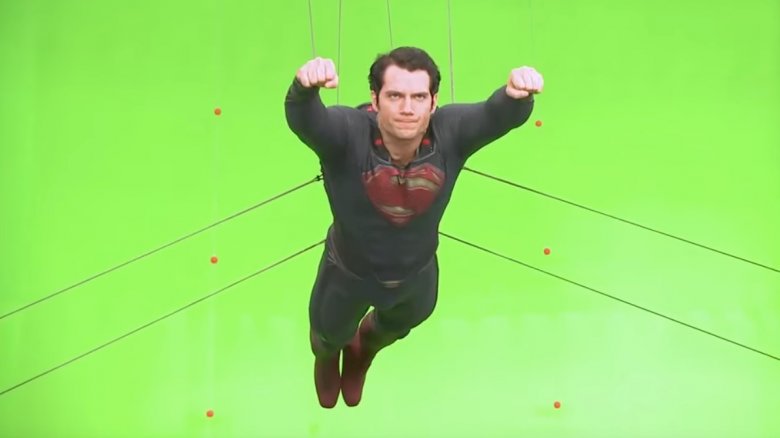

Man of Steel (2013)

To create the illusion of flight, Richard Donner's Superman (1978) employed wire rigs to hang leading man Christopher Reeve in front of different projected backgrounds. The film is a classic, and the effects looked great in the '70s, but watching it today it feels as though you're flying with Superman as opposed to him flying past you—something Man of Steel director Zack Snyder wanted to avoid when he enlisted the help of John "DJ" DesJardin, known for his work on the Matrix sequels as well as Watchmen (2009) and Sucker Punch (2011).

"I think a lot of the direction for the flying came from Zack's style for the movie," DesJardin told The Verge. "He said to us, 'I want this to be really cinéma vérité, documentary-style. I think it needs to be handheld. It's going to be 24 frames, no slow motion. It's going to be anamorphic, so if you look up at the sun there's going to be a big flare going across the screen.' And once we got into that mindset, a lot of camera-style questions got answered really quickly about how the flying should be done." Wire rigs and gimbals were used to suspend Henry Cavill in front of green screens, and DesJardin's team did the rest.

Iron Man 3 (2013)

When the first Iron Man movie dropped in 2008, director Jon Favreau wasn't known for CGI-heavy features, but advances in technology had convinced him to change his stance. "I've always skewed away from using visual effects whenever possible," he said. "I think that there are certain things you can't achieve otherwise, but in the past I've always been reticent to use visual effects to the extent that other filmmakers might. That being said, in the last few years there's been a lot of wonderful visual effects movies where it's beginning to become seamless even to me."

Favreau returned for the sequel, but Shane Black took the reins for Iron Man 3, which contained some of the most trying visual challenges yet. "We wanted the ability to be able to suit up anywhere, anyhow, without a giant gantry," Marvel Studios head honcho Kevin Feige said. The answer was having Tony Stark design outlets he injects just below the skin, allowing him to call the Iron Man suit from anywhere. The scene in which he tests this new tech goes comically wrong when Stark is thrown all over his workshop by his rogue suit, which had to be digitally added to the actor's body after the fact.

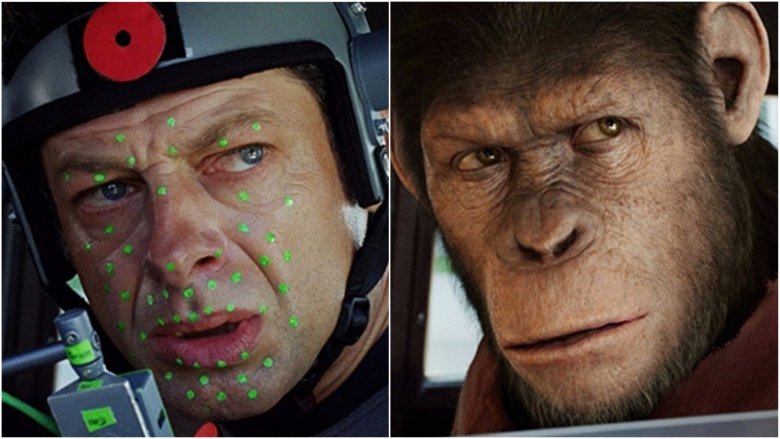

The Planet of the Apes (2011-2017)

Effects studio Weta Digital changed the game when they helped reboot Planet of the Apes with a new trilogy of prequels, beginning with 2011's Rise of the Planet of the Apes. "Weta brought their technology to another level for this movie to make our apes look real," said producer Dylan Clark, who had an equal amount of praise for Andy Serkis. The industry's top performance capture artist shone as protagonist Caesar, redefining screen acting in the digital age. "His facial expressions and body language are so evocatively and precisely rendered that it is impossible to say where his art ends and the exquisite artifice of Weta Digital begins," The New York Times enthused in their review of 2014's Dawn of the Planet of the Apes.

Fox campaigned for Serkis to get an Oscar nomination, but the call from the Academy never came, much to the actor's frustration. "The awarding bodies should not discriminate about this being different," he told Independent after the release of 2017's War of the Planet of the Apes. "The visual effects render the character, just like putting on makeup, except here it happens after the fact. It's digital makeup, if you will."

Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017)

Years of gymnastics training really paid off for Tom Holland on the set of Spider-Man: Homecoming, the character's eagerly anticipated introduction to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Even with the advances in CGI in recent years, it helps to have an actor who feels comfortable jumping around in tights and doesn't mind hanging around on wires all day long. This was the case with the film's Washington Monument scene—but while that was indeed Holland under the Spidey mask, the monument itself was a fake, erected on a studio sound stage.

"We couldn't film at the real Washington Monument, but we built very impressive, very large chunks of the monument for filming," stunt coordinator George Cottle told MTV. Holland got up the structure with the aid of a wire rig, though even with his background it was far from a walk in the park. "We did two weeks and every single shot was upside down," he said. "My head just took a pounding from all the blood that was rushing to it."

The Jungle Book (2016)

While Jon Favreau embraced CGI for Iron Man, the experience he had making that film was nothing compared to what he did for his 2016 live-action adaptation of The Jungle Book. Technology had advanced to the point that photo-realistic digital animals were possible, though to create an entire jungle around a human actor, they needed to pull out all the stops. "It's very hard to fake light and shadow," the director said. "So everything became about using panels of LEDs to project light so if we had the kid bowing before the elephants, you have panels where we actually would pre-animate the elephants and they would cast the shadows on the kid in the exact right way."

This meant that 12-year-old star Neel Sethi had to imagine the animals he was interacting with, though Favreau was on hand to make the experience as real as possible for the young actor. "There were puppets that helped me, so it wasn't just a tennis ball that I was trying to have emotion with," Sethi told Independent. "Jon got into the puppet at times, I got to interact with him, which made it a lot easier."

RoboCop (2014)

Paul Verhoeven's RoboCop got the most out of the special effects available in '80s, using a combination of stop-motion and prosthetic builds to create a movie that was disturbingly realistic at times. A moving, wincing, incredibly lifelike puppet of protagonist Alex Murphy was made by Oscar-winning special effects artist Rob Bottin for the cop's assassination scene, which was so violent that censors forced Verhoeven to edit the part where the back of Murphy's (Peter Weller) head is blown off.

In José Padilha's 2014 reboot, Murphy (Joel Kinnaman) gets his injuries in an explosion that was created digitally, but the suit he dons afterward was actually real. "As the first RoboCop film showed us, a real actor in a real suit makes for a very, very bulky suit," FXGuide's Mike Seymour told Wired, and this was something the special effects team had to counter in their new design. "There was a philosophy from the start that we were going to have a head to toe suit," co-owner of Legacy Effects John Rosengrant said, explaining that his team went to great lengths to design a suit that was mobile and easy for the digital department to add to.

The Martian (2015)

Ridley Scott is no stranger to special effects, but creating the red planet onscreen for The Martian may have been his biggest challenge as a director. While some practical effects were used—the dust storm that Matt Damon gets lost in, for example, was created using fans—a huge amount of digital work was required to give The Martian Scott's desired look. "He's famous for doing his little sketches which are sort of really cool Ridley-grams," VFX supervisor Anders Langlands told Gizmodo. "We'd ask 'What do you want the background mountains to look like in this shot?' And he'd sketch out a little diagram of what they wanted. So you just literally match that and he'd be happy."

A lot of hours were spent finding the right hue for the skies and arid landscapes of Mars, though in the end it was a simple thing that caused the VFX team the most problems. "I think the trickiest thing we came across was actually the reflections in people's visors," Langlands revealed. "Sometimes we'd just take the visor out completely and replace it with a CG one. And then we'd use the environment to generate new reflections that matched what would actually be there."

Harry Potter (2001-2011)

Bringing J.K. Rowling's Wizarding World to life was only ever going to be possible with the help of CGI, and the films made increasingly good use of visual effects with each installment. While early CGI (like the troll in Sorcerer's Stone) hasn't aged well, the quality of digital imagery from Goblet of Fire onward still holds up. The VFX team had to up their game for the fourth film in the series, as it marked the return of Lord Voldemort (Ralph Fiennes). Paul Franklin, the VFX supervisor for Order of the Phoenix and Half-Blood Prince, revealed that creating Voldemort's nose was a mammoth task.

"There's this idea that we put the shots through the computer and it just vanished off [Fiennes'] face," he told RadioTimes. "[His nose] had to be painstakingly edited out, frame by frame, over the whole film. And then the snake slits had to be added and tracked very carefully using dots put on his face for reference." Franklin likened the process to creating a renaissance painting. "The digital brushwork has to be very, very fine to get it to work. The art and time that goes into those nostrils should never be underestimated."

Life of Pi (2012)

Filming this tale of a boy stranded at sea with a Bengal tiger came with a number of obstacles—but the biggest one wasn't the tiger, it was the water. Director Ang Lee had the crew erect the biggest wave pool ever built on a set and shot the entirety of Life of Pi in 3D. "To make an impact with water, you usually need to create a 200-foot wave when shooting in 2D," Lee said at the DVD launch (via Mashable). "I knew that to make it work with 3D, water had to become a character itself. I've never seen realistic water scenes in movies because water hits one side of a tank wall and bounces back like it would in a bathtub, but we needed to make it work."

Real tigers were actually used in some shots, but scenes in which Pi (Suraj Sharma) interacts with the deadly animal were done using a crude CGI-friendly puppet. "Life of Pi is definitely one of the most challenging projects I've ever worked on," VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer said. "We had over 15 artists just working with the fur. Someone has to comb and place all the ten million hairs on its body."

The Hobbit (2012-2014)

Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings trilogy wouldn't have worked if the VFX team didn't nail Gollum, as the CGI character was hugely important to the plot. Weta worked their typical magic on him, but it was the motion-capture performance of Andy Serkis that really brought the devious little creature to life. Serkis reprised the role in Jackson's The Hobbit films, but he wasn't the only actor slipping into a spotted grey suit this time out: Benedict Cumberbatch was brought in to play the trilogy's antagonist Smaug, solely because of his voice.

"It wasn't about what he looked like, it was about what he sounded like and what he was able to produce in the character simply by his voice," Jackson said. "And he knew Smaug, I mean he understood Smaug as well as we did." Cumberbatch revealed that the gravelly tones he gave the psychotic dragon were an imitation of the ones his father used when he read The Hobbit to him as a child. "My dad's an extraordinary actor," the Doctor Strange star said. "He brought this already very rich, magical, visionary world of hobbits and giants and trolls to life."

Game of Thrones (2011-present)

Game of Thrones season finales always have a cinematic quality, thanks in part to the digital wizardry of Pixomondo. A lot of shooting is done on location and green screen use is kept to a minimum where possible, but bringing the creatures of George R. R. Martin's world into the mix requires some top-notch CGI. Pixomondo's VFX supervisor Sven Martin told The Washington Post that one of their biggest achievements has been making Daenerys' dragons blend seamlessly with the world around them, explaining, "This was always our main approach, to not make the dragons too fantastical and too design-driven."

But all that magic doesn't happen until the dragon scenes have been shot, so how does Emilia Clarke connect with her fire-breathing babies? "Well, they have these amazing life-scale models that we used for camera rehearsals for the sake of the CGI people, and I got very attached to them," the actress told Huffington Post. "They genuinely helped me and I kind of got very maternal towards these—fundamentally [they're] dolls, I suppose. But it was nice to have something physical that I could really picture in my mind."

Alice In Wonderland (2010)

Tim Burton was creating stunning visual effects long before CGI came along, using a combination of practical techniques to bring his dark vision to the screen. The former Disney artist used stop-motion animation, miniatures and puppetry to great effect in his earlier works, though when the opportunity to direct his own version of Alice In Wonderland came along, he soon realized that he couldn't do it without leaning heavily on digital wizardry.

"[I] felt like this was the way to go," Burton told FanBolt. "Whether it's stop-motion or cell or CGI, it's still animation." This meant that Johnny Depp, Anne Hathaway and star Mia Wasikowska had to do the bulk of their acting in front of green screens, which was a challenge for the whole team according to visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston."The green screen color, after long periods of time, seems to create a certain aggravation and irritation after staring at it for a long period," he told CinemaBlend. "It is effective for compositing, but visually and psychologically exhausting to be surrounded by it for extended periods of time."

Beauty and the Beast (2017)

When Disney first announced their intention to remake a number of their beloved animated classics in live action format, the title that raised the most questions was Beauty and the Beast. Their rebooted version of The Jungle Book required them to render photo-realistic animals, though at least the protagonist was human. A film in which one of the two leads is a big hairy creature and the majority of the supporting characters are animated household objects was always going to rely on CGI, though director Bill Condon has never liked digital effects and actively avoided using them wherever possible.

"It was important to make everything that could be real, real," he told IndieWire. "I'm not a big fan of CG movies. The idea is to feel grounded in a world and not be distracted by things that felt like additions." Unfortunately for the man portraying the titular Beast, it was motion capture all the way. Dan Stevens (Downton Abbey) spoke to both Andy Serkis and Mark Ruffalo about their experiences in motion capture roles, and their feedback left him sweating. "I think I was mildly terrified," he said. "But that's really, generally what drives a lot of my decisions these days, is calibrating the right amount of terror."

The Dark Knight (2008)

Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight was the first film to shoot scenes with IMAX cameras as opposed to using 35mm and converting in post. The director has "a very astute eye," according to the film's visual effects supervisor Nick Davis, who spoke to StudioDaily about his experience on the Batman flick. "It was important for the visual effects to look as though they were shot on set," he said. "[Nolan] didn't want the film to take on a gimmicky visual-effects look." Taking this route meant that Nolan's first sequel to 2005's Batman Begins was "a difficult movie to finish" as the visual effects had to be rendered in a higher resolution than ever before.

The Joker's look wasn't an issue as subtle prosthetic makeup sufficed, but when it came to the film's secondary villain, Harvey "Two-Face" Dent (Aaron Eckhart), Nolan wanted to remove layers, not add them. "This character was one of our major VFX challenges," Davis told AWN. "We actually removed the skin digitally. It allowed us to reveal the tendons, the cheeks, the eyeballs and to create unique textures." Two-Face's exposed eyeball had to be painstakingly animated by hand, as were the subtle changes in muscle tension.

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016)

As the titular beasts in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter prequel are all fictional, it was difficult for leading man Eddie Redmayne to get acquainted with the creatures he was supposed to adore, so he spent time with animal handlers in the Muggle world to learn how they interacted. "It was really about working out the relationship Newt had with each of the animals and it's not a human relationship," he told Pottermore. "For example, I'd hear some of the sounds these handlers would make. They are not necessarily the same noise as their animal makes but it would be something that the animal reacts to."

Redmayne was able to give a realistic performance because he did his homework, but all of his grunting and squawking would have looked ridiculous if it weren't for the work of Framestore. The London-based visual effects house oversaw the growth of the beasts from flat images into real characters, and they were given a huge amount of creative freedom by director David Yates. "It was an open brief, essentially," VFX supervisor Pablo Grillo told The Independent. "David saw the value in bringing the animation team in from the start, to shape how these creatures were going to come together."

Gravity (2013)

The biggest challenge Alfonso Cuarón faced making his space epic Gravity was achieving a realistic lack of said force on screen, which involved a mixture of practical and digital effects. "It took a lot of education for the animators to fully grasp that the usual laws of cause and effect don't apply," the director said (via Space). "In outer space, there is no up, there is no down." Co-stars Sandra Bullock and George Clooney were advised on their movements by real astronauts before being hooked up to a series of rigs created by Academy Award-winning visual effects artist Neil Corbould.

"Sandra spent many hours inside her 'cage'—a box with LED panels all the way around," he revealed during a Time Out interview. It turns out that Bullock not only had to put up with being suspended from wires most of the day, there were electric shocks to contend with, too. "There was a charge in there like the static you feel underneath an electricity substation," Corbould continued. "If you walked out then touched someone, you'd get this massive shock. We had to earth her every time she went in. It was very effective but demanding." Corbould won his second Oscar for Gravity, having picked up his first in 2001 for Gladiator.

The Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001-2003)

Whenever Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings trilogy comes up during conversations about special effects, the first thing most people mention is Andy Serkis' brilliant motion capture performance, though creating Gollum was just one of many challenges Weta faced during this epic undertaking. Practical solutions were used in places—the forced perspective technique was employed to compensate for the height difference between hobbits and most of the other races in Middle Earth—but the bulk of the visual effects were achieved digitally. Even the interior of Bilbo Baggins' hobbit hole (with the exception of the chandelier that Gandalf bumps into) was computer generated.

Speaking to AWN, visual effects supervisor Jim Rygiel revealed that the Best Picture-winning finale Return of the King was his favorite of the three movies, because of the monumental amount of work he and his team put into the picture. "Return of the King has more shots than one and two combined, it's like 1,450," he said. "It was mind-boggling to figure out logistically how to do them all. It's something you never think you could have done and you did it, like climbing Mt. Everest."

Oz the Great and Powerful (2013)

Scott Stokdyk worked with Oz the Great and Powerful director Sam Raimi on all three of his Spider-Man movies, but creating a credible prequel to The Wizard of Oz proved a far greater challenge for the visual effects wizard. "Soon after Oz finds himself transported from Kansas, he and his balloon enter the jagged peaks environment," Stokdyk said. "To create this part of the land of Oz, artists at Sony Pictures Imageworks custom built digital models of a canyon. Starting from a simple blue screen element of Oz (James Franco) in a basket, the artists created numerous details, filling the depth from the camera to the farthest point in the scene."

Sadly for Stokdyk and his team, the film received mixed reviews, with the heavy CGI use going down better with some viewers than others. "Those who enjoyed the film touted its wonderful visual effects, while those who were less enthralled by it cried out for mercy from the seemingly never ending dull CGI landscapes, sometimes no better than a canvas backdrop," FirstShowing said. This split was represented in the movie's Rotten Tomatoes scores—59 percent of critics and 56 percent of audience reviewers enjoyed it.

San Andreas (2015)

The amount of destruction on show in this Dwayne Johnson-led blockbuster definitely doesn't come cheap, but San Andreas actually cost a lot less to make than many of the big natural disaster flicks that came before it. The production budget was $114 million, according to Variety—roughly half the amount needed to bring Roland Emmerich's 2012 to the big screen in 2009. The film's visual effects supervisor, Colin Strause, was able to keep costs down by employing practical solutions to problems that most visual effects companies would solve with only computers today.

"You can make a $100 million movie look like a $200 million movie," Strause said. "You can make movies way smarter. You don't have to gold plate everything... CG for the sake of CG is always a mistake." Miniatures of numerous landmarks like the Golden Gate Bridge were swilled with buckets of water to save animators some time when it came to engulfing them with tidal waves, though they still had their work cut out for them. Seven different companies worked together to render 1300 VFX shots for the movie, which looks utterly ridiculous before their work is added.

Sin City (2005)

In an effort to convince Sin City writer Frank Miller that he was the right man to adapt his beloved graphic novels for the big screen, Robert Rodriguez flew the famous comic scribe to his Austin backlot (complete with a 30-foot green screen) and filmed a scene from it right in front of him, with Josh Hartnett and Marley Shelton playing opposite each other. The director added the visual effects himself straight away using his home studio, and Miller was sold by the end of the day. That scene became the opening of the movie, which managed to capture the look and feel of Miller's work perfectly.

"Having finished the Spy Kids series, I was looking for a good effects challenge," Rodriguez told Wired. He'd already converted his garage into a post-production suite by that point, and with his own set of Sony HD cameras and four Avid digital editing machines at his disposal, he felt up to the task of recreating Sin City's unique visuals on screen. His indie approach to VFX even converted Tarantino. "Quentin did a scene where the actors are in a car and it's raining," Rodriguez explained. "Instead of worrying about all that stuff, the car and the rain were added later, and he could just get the performance."

Avatar (2009)

James Cameron had been planning his sci-fi epic Avatar for a number of years when he finally decided the time was right to get the ball rolling, a decision he made after seeing Weta turn Andy Serkis into Gollum for The Lord of the Rings. The Terminator director flew to New Zealand to meet Peter Jackson, who convinced Cameron to entrust Weta with Avatar. He still had reservations about the job ahead, however, as he explained to The Telegraph: "We were going significantly beyond anything [Jackson] had done because we had all sorts of different characters based on different actors."

Leading those actors were Sam Worthington and Zoe Saldana, who had to film her scenes as Neytiri in a camera-rigged motion capture suit. Green screen shooting presents all kinds of obstacles for actors, but it's also extra challenging for the person directing them. "My challenge as director is to make it as real as possible for them, and their challenge as an actor is to imbue it with a sense of emotional veracity," Cameron told NPR. "If it's a big dramatic confrontation, the best thing to do is just let them go at it and act off each other." The movie went on to win Oscars for cinematography, visual effects, and art direction.

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest (2006)

The post-credits scene in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales opened the door for the return of supernatural sealord Davy Jones, though actor Bill Nighy had no idea his character was even in the movie until a taxi driver told him about it. The British veteran admitted to Empire that he would be open to reprising the role if Disney had more in store for Jones, whose creation marked a big advancement in motion capture technology.

Jones made his first appearance in 2006's Dead Man's Chest, orchestrated by visual effects supervisor John Knoll. Knoll was able to develop a method that allowed Nighy to be on set with his fellow actors instead of filming separately in front of a green screen, which in turn allowed him to interact more believably and deliver a far more genuine performance. "On a soundstage with 25 technicians staring at Bill and nobody to play off of, that quirkiness would all have gotten ironed out," Knoll told EW. "Somebody would say, that gesture is 'too off' or 'too odd.' It could have become a real sort of committee effort." He was rewarded with an Academy Award for Best Achievement in Visual Effects for his efforts.

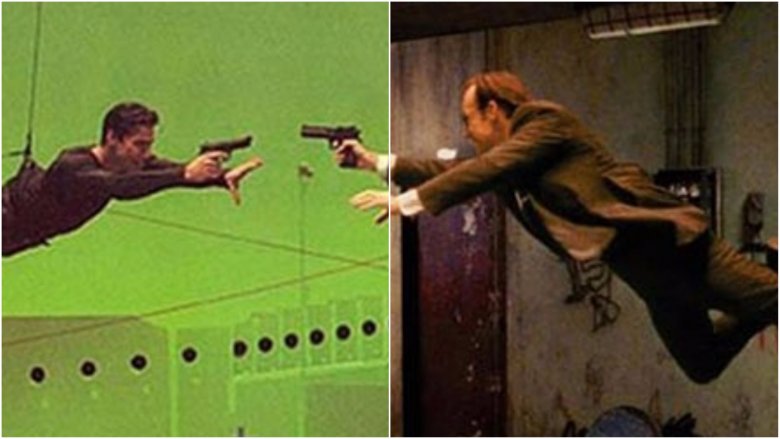

The Matrix (1999)

Arguably one of the most influential films of all time, The Matrix truly changed the landscape of action movies when it dropped at the turn of the millennium, with its memorable fight sequences becoming a benchmark for stunt coordinators and VFX artists alike. Director duo the Wachowskis have openly admitted that they were heavily influenced by classic manga turned cult anime Ghost in the Shell, so much so that they actually took a copy of the film with them when they were pitching to producers. "We want to do that for real," they'd tell them—and to do that, they needed to embrace new techniques.

The term "bullet time" was coined for the epic slow motion shots that the movie employed on the regular, which were created by visual effects guru John Gaeta. The goal was to "create a ballet that could never be staged in real life," the film's experienced special effects supervisor told The New York Times. "The directors wanted to emulate the stylization found in Japanese animation. When we created weather, fire and smoke, we wanted it to move not realistically but impressionistically." Raw footage released as an extra on the DVD showed how bullet time was achieved using an intricate setup of perfectly positioned cameras and masses of green screen.

The Twilight Saga (2008-2012)

With a production budget of $37 million, the first Twilight movie didn't have the funds to create roaming packs of giant CGI wolves, though luckily they didn't come into Stephenie Meyer's story until a little later. By the time the two-part finale Breaking Dawn came along, the franchise was a genuine global phenomenon and the purse strings had been loosened considerably, with a good chunk of the available cash going on visual effects. Physical interactions between Bella (Kristen Stewart) and wolf-form Jacob (Taylor Lautner) began taking place in earnest during third installment Eclipse, but the final showdown in Breaking Dawn – Part 2 was the big test, requiring "full hand animation for up to 16 wolves," according to VFX supervisor Eric Leven.

"The entire battle was filmed on a soundstage in Baton Rouge, Louisiana for six weeks," Leven told Art of VFX. "It was covered with fake paper snow on the ground, which we worked hard not to dirty, and surrounded on three sides with green screen." With dozens of actors involved and time at a premium, the final battle proved a real challenge for everyone. "It seemed a little random and chaotic while we were shooting, but through the editing work of Virginia Katz and Ian Slater, the sequence really came together in the finished film."

The Maze Runner (2014)

Fox's adaptation of James Dashner's The Maze Runner wasn't the best dystopian teen movie to come out over the past decade, but it was far from the worst. The film scored a respectable 65 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, with the majority of their critics praising the premise, acting and visual effects. Method Studios' Sue Rowe was the visual effects supervisor on the project, which proved fun but challenging for her team. The walls of the maze itself apparently kept them very busy—it was created in a huge open field with some strategically placed blue screens.

"The walls needed to be 100ft tall with ivy growing at the tops," she told Art of VFX. "On location we had a section of wall 20 by 40 where we shot a lot of the dialogue shots, however the rest of this 900m square field need to have imposing concrete walls." Rowe also had to dedicate a large chunk of time to the final battle with the Grievers, in which everything but the floor that Dylan Thomas and his castmates stood on was blue screen. As Rowe later admitted, "That was a hell of a thing to pull off."

The Revenant (2015)

Leading man Leonardo DiCaprio and director Alejandro G. Iñárritu both took home Oscars for their respective work on 2015 tour de force The Revenant, though they weren't the only ones to receive recognition. The film was nominated in 12 categories at the Academy Awards, one of which was Best Achievement in Visual Effects. ILM were tasked with creating some of the most challenging animal sequences for the movie, including the moment frontiersman Hugh Glass (DiCaprio) rides a horse off a cliff and the scene in which he's viciously attacked by a bear.

"It's such a pivotal scene in the movie," ILM's Richard McBride told Studio Daily. "It holds a lot of weight as far as its importance in the film." While McBride (the project's overall visual effects supervisor) was proud of the VFX work that went into the bear scene, the real hero was 6'4” stuntman Glenn Ennis, who was the one doing the mauling. "It was incredibly physically demanding," he told Inside Edition. "It was hard on the body, you're on your hands and feet picking someone up and throwing them around." Ennis revealed that working with DiCaprio on the scene was an intense experience because the A-lister's agony was so believable. "I thought I was hurting him, everybody around thought that I was hurting him as well," he said. "He was so powerful as an actor."

Passengers (2016)

The combined star power of Jennifer Lawrence and Chris Pratt helped Passengers turn a profit at the worldwide box office, but back home in the States, Morten Tyldum's sci-fi romance failed to recoup its $110 million budget. The film had more plot holes than black holes, and the majority of critics were quick to pick up on them, though despite the movie's many failings nobody could deny that it looked great. Passengers was Tyldum's first big VFX feature, and the Norwegian director wanted to keep things as subtle as possible throughout, as MPC visual effects supervisor Pete Dionne explained.

"For every sequence, every shot, every detail in the frame, Morten was always clear on what the purpose and impact would be to the story," Dionne told Art of VFX. "His aesthetic is definitely biased towards invisible effects, and where they couldn't be invisible by nature, to keep them restrained and to never distract from the drama." MPC were behind many of the big visual effects shots in the movie, including the zero gravity water sequence and the impressive Starship Avalon, but bringing those scenes to life was no walk in the park. "MPC took on around 1150 shots," Dionne added, "which was a significant number considering how lean the budget was for what Morten required us to achieve."

Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016)

2016's Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice was a pivotal moment for the DC Extended Universe, and Warner Bros. pulled out all the stops to try and ensure its success. The studio was so desperate for the film to do well that on top of maxing out the $250 million budget, it spent a whopping $28 million on TV trailer ads alone, hoping to draw in enough crowds to break the billion-dollar barrier and pose a legitimate threat to Marvel's superhero dominance. The majority of fans seemed to enjoy the movie, but the critics didn't agree, and even though it made a staggering amount of money, it wasn't the jumpstart the franchise needed.

Director Zack Snyder was slammed for making Superman "too dark" by none other than Watchmen artist Dave Gibbons, but he and his visual effects team actually went out of their way to pay homage to the source material in the little details. "Superman's cape is a character on its own, with its iconic zero-g feel where every burst of wind can influence the mood and message of a shot, which at times can be tricky to achieve with Superman's movement," Scanline VFX supervisor Bryan Hirota told Art of VFX. "[The cape] had to act and feel natural, but on the other hand behave in an art-directed way and create appealing shapes that remind the viewer of the original comics."

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 (2015)

The Hunger Games movie franchise came to an end at a time when releasing the final movie of a series in two separate parts was the fashion, and (much like Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows) the second installment was a lot more exciting than the first. "The two films are different in tone and execution," VFX supervisor Charles Gibson told 3Dtotal. "Mockingjay – Part 2 was more of an action/war film with big set pieces playing within The Capitol. We had to enhance battle action and create believable environments that would hold up for extended coverage."

Gibson worked closely with production designer Phil Messina, who joined the Hunger Games team in the early 2010s when the franchise was still in its infancy. "Phil and I had extensive discussions about locations versus building digital sets [and] we agreed that a mix of both would be best for the film," Gibson said. He went on to heap praise on his colleague throughout the interview, claiming that Messina's input on the project was invaluable. "Generally the success was due to Phil's taste—picking compatible locations and coming up with a unified design approach and providing a 'look book' of architectural styles for our vendors."

Independence Day: Resurgence (2016)

The state of the art special effects shots on show in 1996's Independence Day still look great today, though they were made in a very different way than those created for the 2017 sequel Resurgence. VFX supervisor Volker Engel won an Oscar for his work on the first movie, 95 percent of which was done using miniatures and motion-control cameras. The original had 430 visual effects shots in total, while the follow-up contained as many as 1,750. The hard part wasn't the sheer number of shots, however, it was making them resonate with Independence Day fans.

"The tricky part of doing a sequel is that you have to bring back aspects of the original so that the fans are not going to be disappointed, and at the same time you can't tell the same story over again," Engel told 3Dtotal. "There are recognizable designs such as the alien fighter, where you can clearly see that they come out of the same factory. It's just 20 years later." 15 different VFX houses came together to bring Resurgence to life, though Uncharted Territory took the lead, acting as a hub where all the vendors could share their work on the project.

Okja (2017)

South Korean director Bong Joon-ho (The Host, Snowpiercer) turned countless Netflix users vegan in 2017 with his touching action adventure Okja, the story of a little girl and her super pig. The Verge called it "the first great Netflix movie," and the majority of critics certainly approved of the film—itwent Certified Fresh on Rotten Tomatoes with a score of 86 percent. According to the project's VFX supervisor Erik-Jan de Boer, the success of the film hinged on whether the audience believed that Okja, a new kind of genetically engineered pig created to fight world food shortages, was real.

"I explained it to Bong: The only way that people are really going to believe Mija and Okja and their little pet friendship is if we have a lot of contact, and if that contact is truly believable," he told No Film School. "The movie has a lot of really intricate and tender caressing and stroking. Some of that stuff is really hard to do in CGI, and it took a lot of hard work from all departments in post-production to pull that off." The team created a range of foam props for young star Ahn Seo-hyun to interact with, including a full body suit for the most intimate interactions between the girl and her giant best friend.

Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

The sequel to Ridley Scott's seminal sci-fi classic Blade Runner was a long time coming, and everyone from director Denis Villeneuve on down felt the weight of the '80s cult classic on their shoulders, including the VFX team. "It was daunting to have everyone you spoke with poke you in the chest and say 'Blade Runner is one of my favorite films, the sequel better be good,'" overall visual effects supervisor John Nelson told Art of VFX. "I think any fan of science fiction or cinema has a great deal of reverence for the original Blade Runner, myself included."

Rodeo FX came on board and Nelson also recruited Double Negative to create the film's many cityscapes. "It was a big undertaking," the company's VFX supervisor Paul Lambert said. "We knew it was going to be a big job with the added pressure of knowing that the cityscapes in the original Blade Runner had been iconic." The sequel managed to capture the neon-noir feeling that resonated with fans of the original so strongly, but the secretive marketing may have hurt the film's chances of finding a mainstream audience. In the end, it fell below expectations at the box office.

Arrival (2016)

Before Denis Villeneuve imagined the future of mankind in Blade Runner 2049, he directed a sci-fi outing that was a little more grounded in reality. 2016's Arrival follows a linguist and a physicist (Amy Adams and Jeremy Renner) as they attempt to communicate with an unannounced alien species, with large portions of the film taking place in and around one of their monolithic spacecrafts. The VFX style was the polar opposite of his Blade Runner sequel; at times it all seems a bit drab, though that was very much Villeneuve's intention, according to VFX supervisor and regular collaborator Louis Morin.

"He wanted nothing to do with any kind of sci-fi movie that we've been seeing recently from Hollywood," Morin told VFXblog, revealing that Scarlett Johansson-led indie sci-fi Under the Skin was a big inspiration on the project. "The way they shot with a camera with non-actors, [Villeneuve] said he just wanted this movie to feel so real and so boring in so many ways, like, ordinary looking. I remember we were cutting the movie, we spent a lot of time finessing the story in the edit, and we were in Montréal in February, minus 15 or 20 outside with a cloudy day, no color—he said, 'That's what I want.'"

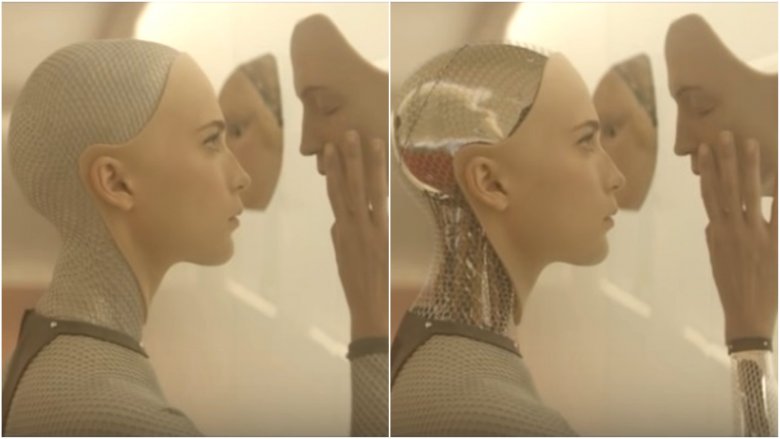

Ex Machina (2015)

Alex Garland's indie sci-fi drama Ex Machina beat out competition from a number of big-budget films to land the Best Achievement in Visual Effects Oscar in 2016, and it did so by being efficient. According to VFX supervisor Andrew Whitehurst, the shoot was so well organized that it ran without a hitch from start to finish, leaving extra cash to spend on making super intelligent gynoid Ava look amazing. "We shot well, we didn't have any reshoots," he told Collider. "With the extra money available to put into more visual effects work, [...] we were able to do the head and the neck as well as the torso and the limbs, which was a good way of working, I think."

The first Ava concept art was done before Alicia Vikander was cast in the role, and the designs were altered with her in mind after she came on board, but one thing Garland never wanted Ava to lose was her sexiness. The Swedish actress was fitted with a skin-tight mesh suit that left very little to the imagination. "We had to work out a way of constructing the whole top of the suit in once piece to show every single beautiful curve of a woman's body," costume designer Sammy Sheldon Differ said. "The end result is fabulous and it was a massive team effort."

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children (2016)

Tim Burton's reputation was built on his inventive use of miniatures and stop-motion techniques, but in recent years, the onetime Disney animator has gravitated toward CGI. Burton first started dabbling with digital effects in Batman (1989) and Batman Returns (1992), and his love affair with computer-generated visual effects has grown in scale ever since. "He remembers when you couldn't even remove a wire from a shot, so he really appreciates what he's able to do now," pointed out Frazer Churchill, VFX supervisor on Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children.

Churchill admitted to being a little apprehensive when he visited Burton's house one morning to discuss the film ("A stone skull at the door threw me off my guard," he revealed while chatting to Art of VFX), but he was offered the job the same day. He set about dividing the work between various well-respected VFX vendors, including Double Negative, Rodeo FX and MPC, but it was Scanline who were tasked with creating the tricky underwater shots.

"I believe that Scanline has built a reputation for producing world class visual effects and in particular crafting state of the art water simulations of any sort," VFX supervisor Jelmer Boskma said. "I wasn't surprised that, when Tim Burton envisioned some rather complex underwater scenes for the movie, his VFX production team reached out to Scanline to help create some of the effects."