How Minority Report Differs From The Book

Having celebrated its 20th anniversary, "Minority Report" has officially become a blast from the past, despite being set in 2054. Stylish and sleek, it predicted a lot of modern trends in surveillance and incessantly intrusive advertising, even if we're not quite at the point of predicting future crimes yet. It also sits comfortably among the top of the list in terms of director Steven Spielberg's best-ranked movies, as well as movies in which Tom Cruise runs a lot (and other Tom Cruise things happen).

But how does "Minority Report" hold up to its own past, when compared to the short story of the same name by sci fi maestro Philip K. Dick? A titan of the genre also famous for the mind-bending stories that became "Blade Runner," "Total Recall," and "A Scanner Darkly," Dick's 43-page story tells a much more compact version of a future with a Precrime division, with a much different version of Cruise's hero John Anderton also falsely accused at the center of it. Both versions dance around deep questions of fate, morality, and the nature of time itself, but the differences are wide-ranging and illuminating. Here's how "Minority Report" differs from the book.

A hard knock precog life

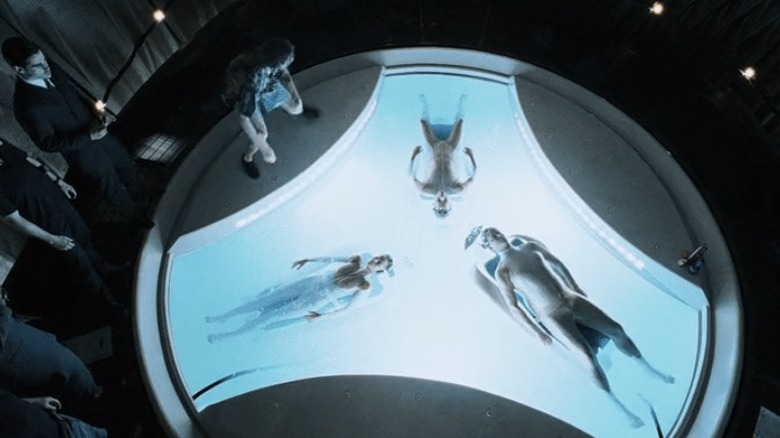

In both Philip K. Dick's original story and the screenplay for "Minority Report" adapted by Scott Frank and Jon Cohen, the entire premise of predicting future crimes is driven by the existence of "precogs," humans with rare genetic mutations that give them precognition, hence the name. In both versions, they live a thankless and terrifying life as basically humans forced to be computer banks, constantly spouting out data about potential crimes, but Dick's is far worse in its particulars. He writes the precogs as severely physically deformed and brain-damaged by the mutations, spending all day spouting gibberish words that computers analyze to predict the future. The characters quite callously refer to the room they're held in as "the monkey house," and no one questions or criticizes their confinement or exploitation.

In the movie, it's still very unsettling that the precogs are forced to live in vats of goo that enhance their abilities, but they're able to recover to semi-normal human lives of self-aware contentment when released at the story's end. The movie tacitly admits how horrible their lives are when our ostensible hero John Anderton says, "It helps if you don't think of them as human," and a tour group of school-children is fed a pack of lies about how the precogs all have plenty of relaxation time and nice apartments to live in. But even though the movie gets a little more into humanizing them — especially Agatha, with her mother's attempt to get her out of the program — the plight of the precogs isn't really a rallying cry in either the movie or the original story.

John Anderton, a murderer after all

The main character of both the book and film "Minority Report" is John Anderton. In Philip K. Dick's story, Anderton is the middle-aged head of the Precrime division, a paranoid and morose man who's worried about his new second-in-command conspiring to take his job. He's married to a much younger woman named Lisa, and he also comes to suspect her of plotting against him, especially when the system predicts that he himself will commit murder. Ultimately, Anderton ends up committing cold-blooded murder on purpose to preserve the integrity of precrime after a sequence of paradoxes that we'll get into later. He's a career bureaucrat, and believes in the order that the system maintains.

Movie John Anderton is wildly different, mostly as a result of being played by likeable movie star Tom Cruise. He's much younger, divorced from a woman named Lara (Kathryn Morris), and is motivated less by a belief in precrime than by throwing himself into his work to avoid grieving his missing son. He's not the head of Precrime, because the movie has invented the character of Lamar Burgess (Max von Sydow), who turns out to be the one who committed murder to preserve the system. Essentially, as part of adding many new elements to expand a 43-page story into a feature film, the movie has divided the book's John Anderton into these two characters, and given all the heroic and derring-do elements to the one played by Tom Cruise. Movie John Anderton, as the clear hero, obviously never chooses to commit murder on purpose.

Three minority reports vs. zero minority reports

Philip K. Dick's story and the movie handle the implementation of the titular "minority report" concept in completely different ways. Each version has three precogs that predict the future, and the title refers to when one of the three disagrees with the other two on the path of future events. Dick's story involves John Anderton reading the minority report of his own predicted murder. One of the precogs has seen a version of events where, since he's informed of the prediction, he successfully avoids killing anyone and the timeline is altered. Ultimately, the third and final prediction is him committing the murder in a completely different way, so in the book Anderton basically has three different "minority" reports, since none are the same.

Movie John Anderton, somewhat ironically, spends most of the runtime of the film chasing down a minority report that doesn't exist: all three precogs had the same vision of his shooting of Leo Crow. Agatha's recurring vision of her mother's death turns out to be a staged recreation of a vision, so it's actually not related to the concept, either. "Minority Report," the movie, doesn't actually show any minority reports, although Anderton makes an off-hand reference to seeing several of them in the archives.

The U.S. Government vs. Precrime

If there were a police division with the ability to predict the future, it's obvious the federal government would take quite an interest. In both the original story and the film, they're attempting to meddle with precrime from the outside. The villain in Philip K. Dick's version is a retired general named Leopold Kaplan, who's listed as John Anderton's intended victim even though they've never met. He turns out to be the head of a shadowy military conspiracy to expose precrime as inaccurate when Anderton doesn't kill anyone, and then to take over the country in essentially a military coup.

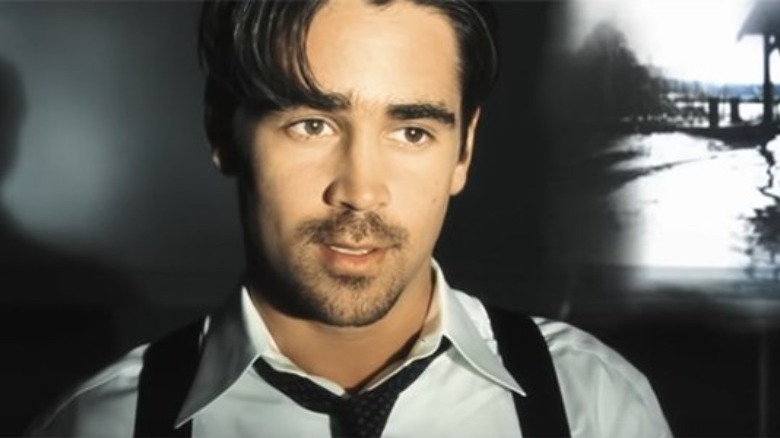

In the movie, it's the Department of Justice that arrives to meddle, not the military, in the form of Danny Witwer (Colin Farrell). The screenplay has precrime at the end of a six-year trail run, instead of being an established national force like in the short story, and the DoJ is there to expose any flaws before a vote to take the program national. As Witwer points out, nobody the Precrime division has arrested has actually committed a crime, making it difficult to grapple with the legality and ethics of the entire experiment.

Precrime: What is it good for?

Neither version of "Minority Report" devotes much time to questioning the morality of arresting people for crimes they haven't yet committed. Even if you take it as a certainty, wouldn't this be a unique opportunity for some kind of therapy or restorative justice for these people instead of just sending them to camps (in the book) or halo-ing them in a cell (in the movie)? Philip K. Dick's characters in the Precrime division are true believers in the cause, as Anderton shoots a man in public to protect the system, and is exiled to a harsh off-world colony at the story's conclusion.

Movie John Anderton comes to question precrime and ultimately plays a role in its shutdown, but only after being targeted by the system himself in an elaborate set up. A lot of dialogue is devoted to the idea of Anderton (and later Lamar Burgess) having a choice in their actions now that they know they've been predicted to commit murder, but no one suggests that they apply this to any of the other accused murderers who have been locked up by the Precrime division.

Witwer, we hardly knew ye

Philip K. Dick's "The Minority Report" and Steven Spielberg's movie "Minority Report" both have a smarmy, obnoxious character named Witwer who seems determined to undermine John Anderton, but who actually turns out to have good intentions. That's where the similarities end, however. The short story's Ed Witwer is a second-in-command who's been forced on the older Anderton with an eye toward taking over his job. He ultimately helps Anderton uncover the plot against him, and ends up taking his job after all when Anderton commits murder and is exiled. But he lives to head the Precrime division and keep the system spinning.

The movie's Danny Witwer is an even slimier operator, a representative from the Department of Justice who snoops into Anderton's private life and is always annoying chewing gum and making snide comments. Colin Farrell plays him as such a sniveling bully that's it a legitimate surprise when he starts asking the right questions and uncovers the murder of Anne Lively, only to be shot in the chest abruptly by Lamar Burgess for his trouble. Even though he doesn't live to see it, the Precrime division is exposed as flawed and shut-down, as he was clearly hoping at the beginning of the movie.

Tension in the Anderton family

In both versions of the story, John Anderton has to balance being potentially framed for murder with a messy personal life, although with very different stakes. Philip K. Dick's Anderton is middle-aged and sour, and suspects his much younger wife Lisa of turning against him the instant that his name comes up as a future murderer. Their marriage is put to the test when she attempts to bring him back to the Precrime precinct to be arrested for his allegedly murderous intent, but he saves her life from a shadowy conspirator who had been hiding on their aircraft, and they reconcile. Eventually she joins him in off-world exile, which is nice of her.

The movie has a much younger John Anderton estranged from his ex-wife Lara, both of them dealing with profound grief over the loss of their son. Sean Anderton went missing while John was underwater at a public pool, and is presumed long dead after six years have passed. After the events of the film, during which John is forced to confront his grief when he briefly thinks he's found their son's killer, they reconcile and Lara is pregnant with another child. So both bleak stories end with a silver lining of regained love, at least.

You still have a choice

On both page and screen, the idea of predetermination and free will are important themes in "Minority Report." Does knowledge of your own future mean that you're unable to change it? The book John Anderton is steadfastly resolved at every instance to either defy or live out the future the precogs predict for him. At first, he tries to get out of town for long enough that the date of his supposed crime passes to prove that he's being framed, until he realizes that it will just prove that precrime doesn't work in the eyes of the public. He then reads a final prediction of how he'll murder Leopold Kaplan, and carries it out in that exact way to prove that it does. It's presented as a choice, but murkily so.

The movie makes this idea central to its climatic moment. After Anderton has exposed Lamar Burgess' misdeeds, a "red ball" predicting Burgess shooting Anderton appears at precrime HQ. But Anderton tells Burgess that he can still choose another outcome, which the older man does by shooting himself instead. "Minority Report" the film eschews philosophy for the dramatic exercise of free will in key moments (Anderton also chooses to arrest Leo Crow instead of shoot him as predicted), while the original story takes a more mechanical path through the concept as each prediction changes Anderton's mind in turn.

The world of tomorrow

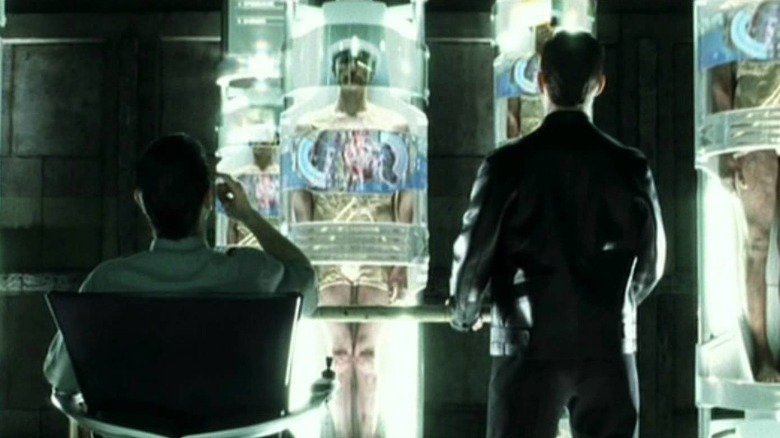

The most vast difference between the stories lies in the details of the futuristic world that they predict. Since the short story was written in 1956, it has many small things that are extrapolations of 1956 technology — projections from a time when computers as we know them barely existed. The precog system relies on printed cards and huge computer banks to analyze data, and Anderton has to open up bulky terminals and make snippets of tape reels to get the information specific to his case that he's looking for.

The movie updates Precrime HQ to include elaborate video screens that show visualizations of what's happening in the precogs' minds directly— a small but arbitrary change is that the murder victims' and perpetrators' names are etched onto shiny wooden balls instead of printed out. The movie also has a lot more narrative time (and a big movie budget) to populate the future with moving digital newspaper images, robotic identity-scanning spiders, and needlessly elaborate police technology like jetpacks and shockwave weapons, which the short story didn't really get into.

The nature of time

Philip K. Dick's short story has a seemingly more nuanced and thorough understanding of how the flow of time functions in its universe. An early passage explicitly states that "minority reports," which happen when the precogs slightly disagree on the details of the future, are somewhat common and actually integral to the idea of precrime itself. If the future couldn't be changed at all, there would be no possibility of stopping future crimes in the first place. So the idea that the future has variations makes perfect sense, given that there's an entire arm of law enforcement dedicated to changing the timeline.

"Minority Report" the movie takes a more binary understanding: there's the future where a murder happens, and the future where the Precrime division gets there in time and stops it, and seemingly no in-between. So the very existence of minority reports is covered up, and the system is designed to delete them immediately. It's not as clean of a thought process, and the movie sidesteps this by never dealing with any actual minority report-related discrepancies.

All's well that ends well

"Minority Report" the movie has as happy an ending as it can muster, as befits a mass-audience PG-13 blockbuster. The precrime division is disbanded — which is good, because Anderton's framing proves it isn't a perfect system and Burgess had to commit murder to set it up in the first place. No one really gets into how poorly the precogs were treated, but they do get to live in a cabin and read books, so they seem happy. Anderton and his wife reunite, and the credits roll without causing us to ask too many more questions.

Philip K. Dick's short story isn't particularly meant to comfort the reader. Precrime itself is a national concern, one that's presumably sent thousands of people to camps for crimes they didn't yet commit. Book John Anderton stops the shadowy military cabal from instituting martial law and overthrowing the country, but doesn't precrime itself mean the country already lives in a police state? Everyone's future intentions are patrolled constantly by an unknown number of poor, exploited precogs, and the head of the division had to kill someone to keep it going.

The right to privacy

"Minority Report" the movie has proven eerily accurate, as it predicted how constant, targeted advertising would become a bigger part of our lives than ever in the years that followed its 2002 release. Granted, billboards and subway ads don't literally say our names aloud after scanning our retinas, but most of us carry a small device in our pockets that tracks our habits and shares our data with advertisers (and often law enforcement) in a very similar way.

Philip K. Dick didn't build the world of his story out into as complex a whole, but the nature of precrime in his version carries similar concerns about privacy. In the story, the precrime division has a national purview and covers all felony-level crimes and upward, implying that precrime police come knocking for much more than just murder. Both stories sketch out the fear and paranoia that would result from living in a vast surveillance state, whether it's your thoughts or your movements that are constantly patrolled and analyzed.