Details You May Have Missed In Gangs Of New York

In "A Personal Journey Through American Movies," the legendary director Martin Scorsese recalls how he was first inspired by Cinemascope historical epics like "The Ten Commandments" that he grew up on in the '50s. Four decades years into his professional career, after warming up with smaller-scale historical films like "The Last Temptation of Christ" and "Age of Innocence," he'd finally accumulated enough Hollywood clout to make a lavish epic of his own, even recreating 19th-century New York in the same Roman studio that had once housed some of Hollywood and Italy's biggest epics.

Combining that genre with the gangster narrative he explored in movies like "Goodfellas" and "Casino," "Gangs of New York" vividly recreates the birth of the mob in the barely civilized city of the Civil War era. And it's helped by an all-star cast led by Leonardo DiCaprio and Cameron Diaz and supported by a who's who of great character actors: John C. Reilly, Brendan Gleeson, Jim Broadbent, Liam Neeson, and Daniel Day-Lewis giving one of the greatest performances in a career full of great performances as crime kingpin Bill the Butcher.

All this spectacle is wrapped up in the oldest story, of DiCaprio's Amsterdam seeking revenge on Bill for the death of his father, Priest Vallon (Neeson). But the backdrop for this simple story is so complex, it's almost impossible to catch it all. With that in mind, we've put together some of the most fascinating details you may have missed in "Gangs of New York."

Everyone in the Old Brewery has a story

Anyone can create a whole world on a Hollywood backlot (or green screen) if they just throw enough money at it. What's harder is making it feel lived in, but Martin Scorsese accomplishes that from the first scene of "Gangs of New York."

While Priest Vallon takes his Dead Rabbits gang to war with Bill's Natives, leading his followers from the ruins of the Old Brewery and the caves beneath it, it would be easy to just get a bunch of extras to stand around behind them. Instead, we get to see the Brewery not just as a gangster hideout but a living community. Vallon walks past an old man sleeping on the floor at one point, and at another, the camera pulls back to show the hundreds of stories playing out in the backdrop, including a married couple fighting while their neighbors drink from a bottle.

The gangsters are even more colorful. This should already be obvious from the speaking roles like Priest in his clerical robes or real-life gangster Hellcat Maggie with her sharpened teeth and clawed gloves. But that's just as true for the dozens of nameless background soldiers. Some go into battle wearing medieval-style executioners' hoods, including one who's drawn a Cheshire Cat grin on his. Another wears a leather strap across his face, apparently to replace a lost nose, and yet another wears a spiked headband. All these strange details suggest whole characters in a few brief moments, showing everyone here has just as much a life of their own as everyone in the real world.

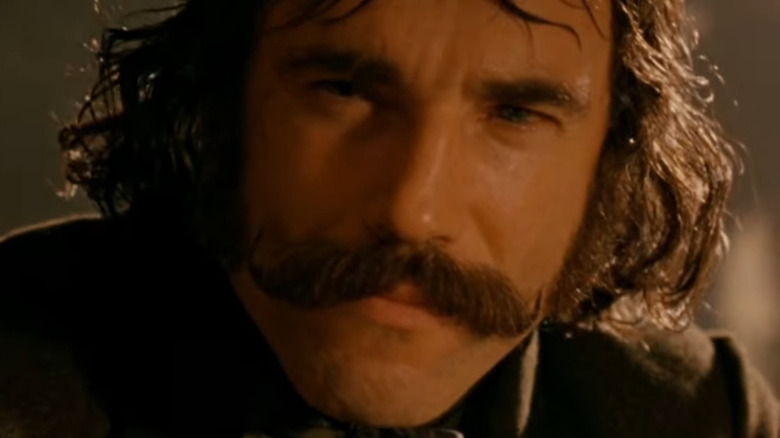

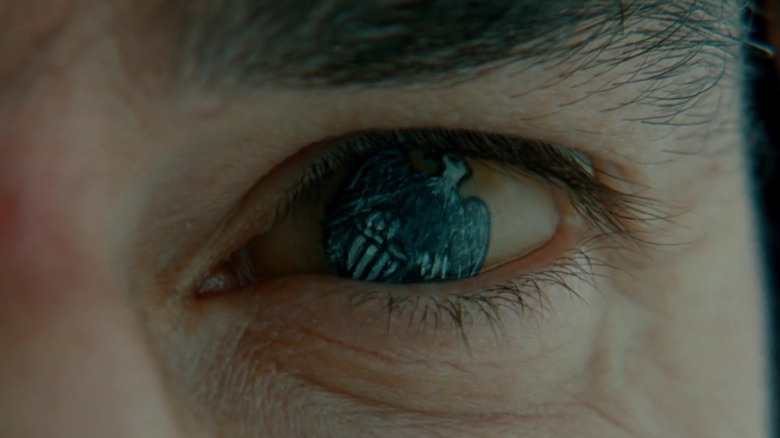

The shape in Bill's eye

The first and last we see of Bill the Butcher is his glass eye. We later learn that the wound is self-inflicted — after Priest gave Bill the beating of his life, the Butcher "cut out the eye that looked away." His replacement, with its cracked, irregular shape, might seem at odds with the rest of Bill's dandy ensemble. But look closer, and it turns out to be just as opulent as anything else in the Butcher's wardrobe.

The irregular shape is actually a bald eagle holding a shield engraved with the stars and stripes. This kind of imagery establishes the fanatical nationalism that motivates Bill to terrorize the waves of Irish immigrants, including Vallon and his gang, flooding into New York. And that's about as subtle as he gets in proclaiming his political affiliation — it's hard to forget the iconic scene where he literally drapes himself in the American flag.

Bill is the only one who makes the American Dream work

"Gangs of New York" is shockingly cynical about American history, and it must've been even more shocking when it was released, at the height of post-9/11 flag-waving. And Bill the Butcher embodies the worst impulses of that era, using his patriotic fervor to justify violent acts of racial and religious bigotry. As the poster says, "America was born in the streets" — built not by great men but by gangsters. An election held late in the film is a sham, with Dead Rabbits press-ganging men off the street and shaving their beards so they can vote multiple times, and that's still not as effective as a blow to the head. Immigrants chasing the American Dream find only abject poverty and violence.

While their immigrant status dooms most characters to the margins, there's still one character who proves the dream that anyone can achieve wealth and power in America if they just work hard enough — Bill the Butcher. Orphaned young and still barely literate, after Amsterdam mentions his childhood in Hellgate Reformatory School, Bill confides, "I was raised in a very similar establishment myself. Now everything you see belongs to me." But given the brutal means by which he gains and uses that power, Bill's success can only make viewers more skeptical of the Founding Fathers' promises.

Peter Gabriel shows up on the soundtrack

Martin Scorsese reveals on his audio commentary (via Film School Rejects) that at one point during the decades-long development of "Gangs of New York," he conceived it as a "punk rock musical" with original songs by the Clash. That obviously never panned out, and the final film has a much more period-appropriate soundtrack.

But Scorsese's earlier vision of modern-day musical cues survives in the pivotal battle between the Dead Rabbits and the Natives. Peter Gabriel fans may recognize the dissonant, electronic score as the instrumental to his song "Signal to Noise." And considering that song appeared on Gabriel's album "Up" the same year "Gangs" premiered, it's almost as if Scorsese was going for maximum anachronism by choosing the newest song possible. Non-Gabriel fans may recognize him as the original frontman of the pioneering prog-rock act Genesis or the artist behind monster solo hits like "Sledgehammer" and "Solsbury Hill." Scorsese fans should certainly recognize him since he composed the score for the director's "Last Temptation of Christ."

The soundtrack revives long-lost genres

Martin Scorsese was one of the first directors to use existing pop music to score his films. These music cues help establish the setting of his 20th-century gangster epics, but how can you get the same effect when you're reaching back to an era before recorded music existed?

Well, you do your homework, and if that sounds boring, the results are thrilling. The conflict over the immigrants' Irish heritage is underlined with a selection of traditional music, including one powerful scene where "Paddy's Lamentation" (a song that dates back to at least the 1860s) is interrupted by military marches as we see immigrants get off the Navy ship and coffins come off. And Finbar Furey sings the old-timey sea shanty "New York Girls" as he leads the viewer through the Satan's Circus pub.

The film also revives some genres that have been almost forgotten. The church that turns the Old Brewery into a mission leads worship with Sacred Harp singing, which Tom Moon describes in "1000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die" as a communal form using "shape notes" to reach illiterate worshippers, in which a group of musicians sing to each other in a circle. "Gangs" underlines its tensest scenes with the piercing high notes and furious rhythm of fife and drum music, a combination of military marches and traditional African music into a kind of proto-blues that dates all the way back to the Revolution.

Gangs of New York has a ton of period vocabulary

Martin Scorsese deliberately mixed anachronisms into the world of "Gangs," describing his approach on the film's commentary as "opera" rather than straight history. But it's still painstakingly accurate in the details, especially the language, even if it pulls them from many periods. The average 19th-century American had a vocabulary we'd consider college-level today, not to mention all the words that have disappeared entirely. It would take an article that was twice as long and took three times as long to write to cover them all, but here are a few to start with.

Some of these words are clear from context. For instance, Amsterdam describes Bill throwing "pavers" at immigrants, and you just have to look at the flying rocks to understand what that means. Similarly, when he asks for some "timber" and gets a light for his cigarette, it's obvious he means a match. The wonderfully old-timey "rowdydow" would be easy to put together just because it contains the word "rowdy," even if we didn't see Bill violently showing what he means.

Other bits of vocabulary need a little more explanation. "Excrement" is already a little-used word (for, in the simplest possible terms, "poop") before Bill mutates it into his description of Ireland as an "excrementitious isle." The multiple references to "glims" are harder to suss out, even if phrases like "look him in the glims" let you mentally substitute "eyes" without thinking. And then you have the words that aren't even English — multiple characters respond to news with "bene," a Latin loanword for "good" they would've picked up at Catholic mass.

Mean Streets callback

"Gangs of New York" works well as a summation of Martin Scorsese's career — you could just as easily use the same title for "Goodfellas," "The Irishman," or his breakout hit "Mean Streets." Ignoring the high-level dons that star in most mob movies, "Mean Streets" instead focuses on Harvey Keitel as low-level soldier Charlie as he struggles to reconcile his Catholic faith with his dirty business, all while grappling with his loyalty to his screw-up buddy Johnny Boy (Robert DeNiro).

In one famous scene, Johnny and Charlie go to collect a debt from a bartender ... and then Johnny ruins it, demanding he turn down the music and insulting his clientele. The bartender refuses to pay because, "We don't pay mooks." Thanks to that insult, the negotiation degenerates into a brawl, but only once the gang can confirm they've been insulted. For a while, all they can do is ask each other, "What's a mook?"

"Gangs of New York" is full of classic movie tributes, but Scorsese can't resist referencing his own back catalog either. After Amsterdam pulls his first job for Bill, robbing a ship and selling the captain's body to a doctor when he discovers another gang has beat them to everything else of value, Bill's toadie, McGloin (Gary Lewis), calls Amsterdam a "Fidlam Ben," which only succeeds in confusing him. If anything, Mature Scorsese is improving on Young Scorsese's material, drawing out the conversation ("Now see, if you'd said we were chiselers, that I'd understand") for maximum comic effect before it explodes into violence.

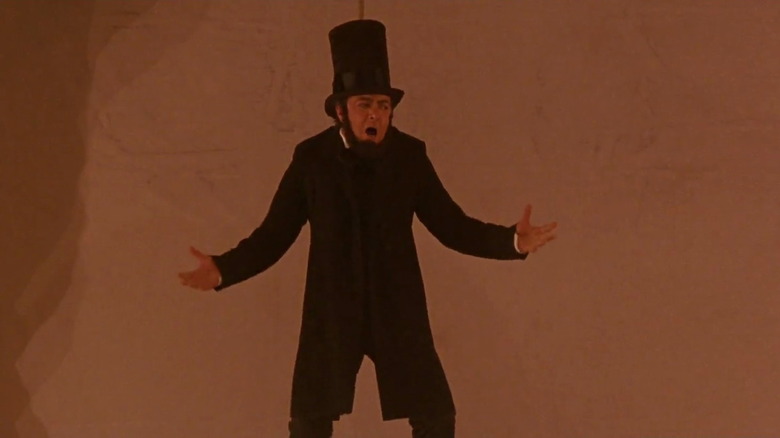

Poor Lincoln got left hanging all through the theater fight

To get close enough to kill Bill, Amsterdam ingratiates himself into the mob boss's inner circle, eventually earning a seat next to him in a production of "Uncle Tom's Cabin." But the producers seem to have taken some liberties since this version ends with Abraham Lincoln himself descending from the heavens to make sure everyone gets a happy ending. The Nativists, who despise Lincoln both for supporting emancipation and passing the Draft Act, start a riot that only gets worse when an Irishman takes a shot at Bill.

And all through this chaos, poor Lincoln is still hanging in midair, pathetically kicking his little legs. Even when we get back from Amsterdam's time-out backstage wrestling with both ex-Dead Rabbit Monk (Brendan Gleeson) and his own guilt over saving Bill's life, Lincoln is still there. The stagehands apparently noped out as soon as things turned violent. For all we know, he could still be hanging there now.

The framing traps Amsterdam as much as his actions do

Martin Scorsese is unparalleled as a visual storyteller, using every aspect of film language to establish story and character. While some viewers won't notice these tricks, that doesn't matter — they still subconsciously affect the experience.

For instance, we see Amsterdam at his lowest point (so far) after he not only saves the man he's pledged to kill but condemns a man to death for pursuing the same goal as him. His plot to get close enough to Bill to kill him has become a trap, boxing him in between his obligations to his dead father and his new father figure. Some of that comes through in the dialogue and in Leonardo DiCaprio's performance, but we can't afford to overlook the effect of the cinematography by Scorsese's longtime collaborator Michael Ballhaus. When we see Amsterdam driven to tears by the trap he's set for himself, we also see him trapped since Ballhaus shoots DiCaprio through a hole in the wall.

There's another possible interpretation of that shot — Scorsese could be returning to an old tricks he used way back in "Taxi Driver" when Betsy (Cybill Shepard) breaks up with Travis (Robert DeNiro) over the phone. The camera moves away to an empty hallway, and this distancing perversely makes the scene even more powerful, as if it's too painful for even the camera to watch. You can see some of the same idea in the scene of Amsterdam backstage. It's certainly present in a later scene where Bill discovers Amsterdam plans to kill him and then drops out of frame, leaving nothing visible but the out-of-focus wall behind him before we can see his reaction.

The Battleship Potemkin reference

Only a few filmmakers are as good as Martin Scorsese, and even fewer know as much about film history as he does. If it wasn't already evident from his work on the Film Foundation and its World Cinema Project, it should be from the dense network of references to classic cinema in his own movies.

For instance, when the draft rioters attack the aristocratic Schermerhorns' mansion in "Gangs of New York," we get a faux reaction shot from the stone lion on their stairway. Silent film fans may recognize this scene from Sergei Eisenstein's Russian classic "The Battleship Potemkin." Created to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the 1905 Russian Revolution, the film retells the true story of a mutiny that inspires a (fictional) protest on the Odessa Steps. In one of the most famous and influential scenes in cinema history, the military brutally responds, shooting a child and sending a stroller racing down the stairs until the Potemkin's cannons open fire on them. Eisenstein follows this with one of the boldest examples of his experimental technique of Soviet montage — juxtaposing three lion statues so that they seem to be one lion waking up and reacting to the carnage.

While the scene in "Gangs" isn't quite as bold, it still makes a fitting tribute from one master to another. And given that both movies feature a battleship firing on a city in the middle of a riot, it's hard to imagine the similarity is a coincidence.

Bill literally idolizes the flag

Bill the Butcher's rabid nationalism eventually leads to his downfall as political kingmaker Boss Tweed (Jim Broadbent) progressively cuts ties with him to court the Irish-American vote and Amsterdam finally gets his revenge for the racially motivated murder of his father. And when we say Bill is rabidly national, what we really mean is that it's basically his religion.

How so? Well, we see just how deep Bill's obsession goes in the montage of prayers the night before his battle with Amsterdam. Scorsese's lifelong editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, cuts between Bill and Amsterdam each praying for strength in their struggle against the other, while the comfortable Schermerhorns make less impassioned prayers of thanksgiving. Amsterdam prays at the altar of the Catholic church under construction in the former Old Brewery. Meanwhile, Bill has his own makeshift altar — an American flag draped over a table, with no religious sacraments in sight. Once you put this together, it all makes perfect sense. Bill's vision of "America for Americans" is his God, one he will follow through rivers of blood and his own self-destruction.

The draft riots are a dark mirror of the church standoff

Most of us learn in school that history is made from the top down, by presidents and kings. One of the main themes of "Gangs" is that history is instead made from the bottom up, "in the streets."

Two sequences, in particular, show the power of ordinary people's collective action — both for good and for destruction. First, there's when all the Irish of New York gather at the Brewery Mission to intimidate the Nativists out of burning it down, and then there are the wildly destructive draft riots. One shows the community's power to protect itself. The other involves many of the same people, but they have no clear target for their anger, descending from justifiable wrath at the wealthy who can buy their way out of the draft to racist violence against Black New Yorkers by some twisted logic, as if they were somehow responsible for the war.

Martin Scorsese makes the connection clear through the visuals. As Amsterdam says, "All you need is a spark. Right? Just one spark. ... And the sky's on fire." Fiery imagery is all over these two sequences even before things start burning down. Just as the Irish hold up candles against the Nativists' torches at the Brewery, New Yorkers put candles in the window to signal they want the draft riots to continue. In the end, the rioters all but destroy the city — but in the last scene, Scorsese shows how that made the city we know today possible as the modern skyline grows out of the ashes.