12 Pieces Of Lost Movie Media That Were Found Years Later

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Although it might be hard to believe in an age when streaming services offer tens of thousands of viewing options, films weren't always thought of as long-term entertainment. Particularly in the first half of the 20th century, a movie would play in a handful of theaters and then audiences could reasonably expect to never see them again — particularly if they didn't make money, become an Oscar winner or do anything else notable during a theatrical run. In those days, film prints took up a lot of space and deteriorated without careful attention, so destroying them was common — and even as television, home video and DVDs eventually began giving films a secondary market in the century's latter half, rights holders might still commonly destroy or disregard decades-old movies, leaving many on the verge of extinction.

From silent era cinema to animated movies both old and new, it can be overwhelming to think of all the cinematic history lost to time. But thankfully, the modern age of film preservation, video sites and social media sometimes comes together to suddenly resurface such footage. Somewhere out there right now, perhaps, some teenager is discovering the director's cut of "The Magnificent Ambersons" in their grandpa's attic, digitizing it and uploading it to YouTube. One can only hope.

It's always a thrill when something presumed to be lost to the sands of times ends up resurfacing. This occurrence has become more frequent in recent years, thanks to the internet and sites like Lost Media Wiki. From being buried in a janitor's closet to a Blu-ray's hidden files, such footage can pop up just about anywhere. Below is a slew of movie media thought to be lost forever that ended up being found, either partially or in its entirety.

Frankenstein (1910)

When it comes to movie villains, few names echo through pop culture like that of the Frankenstein monster. As far as adaptations of Mary Shelley's iconic novel are concerned, the first version most people think of is the 1931 version starring Boris Karloff. Contrary to popular belief, however, that James Whale-helmed version was not the first to hit the silver screen.

In 1910, J. Searle Dawley adapted "Frankenstein" in conjunction with Edison (yes, as in Thomas Alva) Studios. Given the still-developing nature of motion pictures at the time, the film was low budget and presented as "a liberal adaptation" of the story. Clocking in at a meager 16 minutes, the short depicted the monster as being created via various chemicals, not stitched up body parts.

Considered by some to be cinema's first horror film, this initial cinematic depiction of the "Frankenstein" tale has enormous historical significance in a medium that — after 100 years of films from Whale to Abbott & Costello to Mel Brooks, Robert DeNiro and Adam Sandler — is still obsessed with the big green guy. This is where it all began.

Despite such significance, the silent version of "Frankenstein" was believed to be a lost film for decades. Alois F. Dettlaff, a Wisconsin film collector, purchased a surviving print from his wife's grandmother in the 1950s — completely unaware of its significance. In 1993, he screened Edison's "Frankenstein" for the first time in decades. After Dettlaff's passing, the once-lost film was properly restored by the Library of Congress, and the Public Domain result is now just a click away from frighting and delighting once again.

The Intruder (1975)

Media, be it film or television, can become lost for a bevy of reasons. In the case of the 1975 slasher film "The Intruder," the distribution company simply opted to shelve it.

This flick from writer/director Chris Robinson cost a mere $25,000 to make, bankrolled by an investor who needed to quickly spend the money as a tax write-off. Inspired peripherally by Agatha Christie's "10 Little Indians," told the eerie tale of eleven visitors, brought together on a remote island looking for gold — and soon finding themselves picked off, one at a time. What makes the film worth remembering, however, is that it happened to feature such notable actors as Mickey Rooney, Yvonne De Carlo and Ted Cassidy (the latter two of "The Munsters" and "Addams Family" fame, respectively) and was a rare slasher film predating both "Halloween" and "Friday the 13th."

Despite being a movie from notable Hollywood vet Robinson — a longtime actor with 100 credits, including classic TV series like "The Virginian" and "Wagon Train" — it ultimately never saw the light of day because of behind-the-scenes conflicts with distributors. Regardless of how it ended up there, on the shelf is where "The Intruder" remained for decades. Even the director never got to watch it.

"I cast it, put the crew together, and shot it, all within six weeks," Robinson would later say about the film's unusual production. "I have no idea [what happened next]. I wasn't involved in the editing and didn't even see the finished film which was never released. I moved on to other projects and just forgot about it."

Some 42 years later, the horror flick received a happy ending.

"I discovered the film in a storefront storage location on the outskirts of the Mohave desert along with hundreds of other films that had been neglected and left to rot under terrible conditions for decades," film preservationist Harry Guerro said in an interview about how he unearthed "Intruder." "I was not familiar with the film at all — no one was. The film had no Internet Movie Database entry and didn't appear on any filmographies of the principals."

Following its rediscovery, restoration efforts and an at home screening, "The Intruder" finally received a 2017 Blu-ray release.

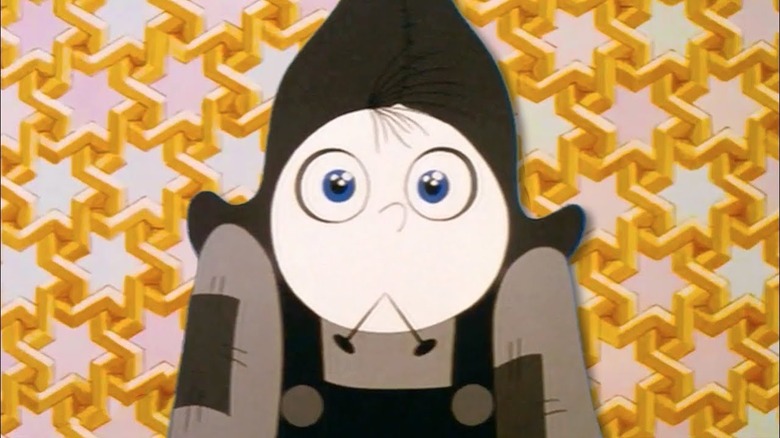

Genndy Tartakovsky's Popeye

In the early 2010s, Genndy Tartakovsky was on both a creative and financial hot streak. Long beloved for projects like "Dexter's Laboratory," "Samurai Jack" and the stunning 2003-2005 "Star Wars: Clone Wars" shorts, his daring animation instincts had become counterbalanced by the formidable box office of the "Hotel Transylvania" series. Suddenly, he turned his sights to a longtime passion project.

"Popeye" had become comic strip royalty via King Features syndicate, and the sailor's debut in 1929 almost immediately proved ideal for mixed media. Max Fleischer adapted the character into a series of popular Paramount Pictures shorts, which existed in some form of production from 1933 to 1957, as the character went on to sell everything from candy cigarettes to ... of course ... canned spinach. A 1980 Robert Altman-directed film notoriously nearly killed the master filmmaker's career, but in some ways helped create the comics-to-film medium that remains so popular today. "Popeye" even became a videogame trailblazer.

Tartakovsky, who cites Fleischer animator Gordon Sheehan as his "very first teacher," became determined to return the squinting sailor from Altman-induced movie jail, bringing him renewed relevance via zany CG animation in the "Transylvania" tradition. By 2012, he was attached to direct "Popeye" for Sony Pictures Animation, with the studio even going so far as to release test footage and a hype reel in 2014 to promote the film. Unfortunately, Tartakovsky and the studio ultimately wanted very different things from the denizens of Sweethaven.

"We did a screening, and it was great. Internally, everyone was super happy with it. I think it was also exactly what King Features wanted. We had a great reaction," Tartakovsky said in a 2015 interview, noting that all this coincided with the infamous Sony hack. "After the screening, I didn't get an answer from them, which was weird because everybody was so positive. Usually, we meet and talk, and get notes. But they had a meeting on their own, and that was it. I just got a phone call afterward telling me how great it was, which always makes me suspicious. If they just call to tell you it's great, there's something going on, because they didn't offer any notes. Later on, I personally went to see [Sony Chairperson] Amy Pascal, and said, 'Look, I'm a big boy. I can take it. I just need some information.' And she said, 'Look Genndy, we love you, but we just don't like Popeye.'"

Ultimately, the project was shelved, and all material related to its production remained in Sony's possession. In 2022, the full animatic for Tartakovsky's "Popeye" suddenly appeared on YouTube, and was just as quickly taken down. Fast-moving fans, however, were able to view (and in some cases, archive) footage of a young Popeye (Tom Kenny) in pursuit of his lost father and place in the world, sent on an oceanic adventure with Olive Oyl (Grey Griffin), encountering sea creatures and sky pirates. Perhaps someday, Genndy Tartakovsky's "Popeye" can be enjoyed in some form.

Richard Williams' The Thief and the Cobbler

"The Thief and the Cobbler" was set to be the masterpiece of one of animation's true journeymen; instead, it was largely lost to time.

Richard Williams, best known for his role as animation director on "Who Framed Roger Rabbit," began work and development on "Cobbler" in 1964, with fundraising largely generated by Williams himself. But the film's animation, far more meticulous and demanding than most other productions at the time, would prove to be its biggest hurdle.

For nearly 20 years, Williams labored over the film in his spare moments; by the 1980s, he had produced only about 20 minutes. In a 2012 documentary entitled "Persistence of Vision," Williams and his colleagues looked back on the project's maddening process.

"I've mastered this medium at last," Williams remarked. "And I'm going to do a masterpiece, I hope. If I can ever finish the thing."

After the success of "Roger Rabbit," studios were intrigued by Williams' passion project, and Warner Bros. entered into a 1988 production deal with him to finish it. All seemed fine, but the film's complex nature continued to delay the project, and in 1992 the film (which WB had hoped to release as competition for Disney's "Aladdin") was taken away from Williams with 15 minutes left to be completed.

Thanks to the sort of long, winding, artistically-compromising roads that only exist in Hollywood, "The Thief and the Cobbler" became two subpar films — 1993's "The Princess and the Cobbler" and 1995's "Arabian Knight" — that featured massive changes, including the addition of voices and musical numbers. But fans of Williams' work have become increasingly determined to help the now-approaching-90 animator restore and finish his magnum opus.

Restorationist Garrett Gilchrist has led much of this effort, releasing multiple "Recobbled cuts" that have restored previously-excised parts of the project. Built off an unfinished work print, this "2019 Recobbled Cut" is the best effort yet to showcase the film's truly intended form.

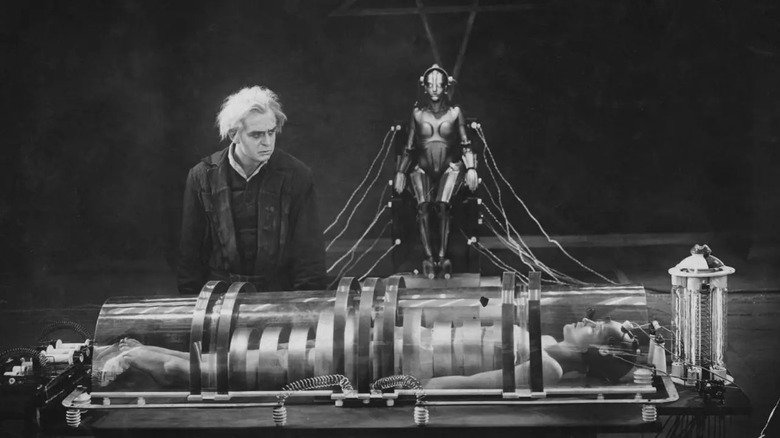

The unedited version of Metropolis (1927)

In the pantheon of influential films, few can compete with "Metropolis." The brainchild of German director Fritz Lang, the film was an ambitious, grand look at a dystopian future. Created during the era of the German Reich, the film is set in a stylistic future with a class divide between workers and the elite.

Freder, the son of the city's leader, looks to help a kind woman named Maria in her goal to unite the classes. The trailblazing visuals of "Metropolis" have become synonymous with cinema — from the lavish designs of the city itself to the Maschinenmensch (machine-person) seen on its promotional materials.

For a film so iconic and influential, it's surprising that for decades, the versions audiences were watching weren't even complete. Following the film's original premiere, the full print of the film was lost; subsequent versions were truncated. Over the years, many would attempt to reconstruct Lang's original film rediscovered and salvaged assets, but it seemed like a losing cause. It wasn't until 2008, when German film experts announced the discovery of a once-lost 16 millimeter print in Buenos Aires that the film could finally be seen as it was intended, all the way back in 1927.

The Spanish version of Dracula (1931)

Tod Browning's "Dracula," starring Bela Lugosi, was the first time sound and cinema came together to depict the vampire tale — and nearly 100 years later, perhaps still the most famous. From the soundtrack to designs of the castle to Legosi's hypnotic stare, everything about the film influenced everything that came after. With this legacy in mind, an interesting footnote is the less-discussed Spanish version of "Dracula."

As noted in Lisa Jarvinen's 2012 tome "The Rise of Spanish-Language Filmmaking," in those days different versions of movies were often made for the Spanish market. Typically these versions were given little press within the United States and were, more often than not, inferior in terms of budget and production.

The Spanish version of "Dracula" employed the same sets, but an entirely different cast. What is perhaps fascinating about this Spanish version is how distinct it is from its American counterpart, even outshining it in some regards. While nowhere near as terrifying as Legosi, actor Carlos Villarías played an exemplary Count Dracula, complete with a set of crazy eyes, and there's plenty else to recommend.

The Spanish "Dracula" was largely forgotten for many decades following its release, slipping into dusty obscurity alongside lesser known films. In the 1970s, however, a copy of the film was discovered in, of all places, a warehouse in New Jersey. This allowed for the lesser known, foreign bloodsucker to properly receive its praise and attention.

George Romero's The Amusement Park (1973)

The landscape of horror, and indeed pop culture as a whole, would be vastly different without the involvement of George A. Romero. Although he didn't invent the concept of the zombie, he most certainly minted the modern-day take via 1968's "Night of the Living Dead," and followed up on his unexpected hit with classics like "Dawn of the Dead" and "Day of the Dead."

With such an iconic name behind it, it's astounding that a Romero film could end up lost to time. But in the case of his 1975 psychological thriller "The Amusement Park," that's exactly what happened.

Aiming to address society's mistreatment and general neglect of the elderly, the film features Lincoln Maazel in multiple roles, navigating a fractured psyche, as well as a freak show exploiting senior citizens.

Following its 1975 premiere in New York, the print of "The Amusement Park" would go missing; it turned up a quarter-century later at a Romero film retrospective. That 16 millimeter copy was then sent to Romero and his wife in 2017. Following Romero's death, the horror streaming platform Shudder acquired the streaming distribution rights and finally made the film available online in 2021. It's a surreal addition to Romero's filmography, making its rediscovery all the more fascinating.

Disney's Kingdom of the Sun

It's fascinating to get glimpses of what a now-famous film was originally intended to be early in production. This is particularly true of 2000's "The Emperor's New Groove," a well-received, self aware buddy comedy conceived as a radically different film.

Originally helmed by Roger Allers, "Kingdom of the Sun" would have been a much more serious film, heavily entrenched in Incan lore. Allers, the director of "The Lion King," looked to bring that same level of reverence and grandeur to the follow-up, which followed a selfish emperor — but that's pretty much where the similarities between "Kingdom" and "Groove" ended. Yzma was a far more menacing villain, there were song sequences, and the llama didn't speak, let alone crack one-liners.

As outlined in the 2002 documentary "The Sweatbox," the project was deep in production when Disney opted to shift gears on the animation team. Following the box office disappointments of "Pocahontas" and "The Hunchback of Notre Dame," Disney no longer saw value in seriously-minded animated movies.

The film as it had been intended was scrapped, and a more comedic version instead was greenlit. In the years since this changeover, Allers has spoken out about his immense disappointment over the project's abandonment. Various assets from the original version have appeared online, and such leaks have been eye opening — but frustratingly, they are brief glimpses of an ambitious film that will never be completed.

The Pagemaster's deleted Frankenstein sequence

"The Pagemaster" is a gloriously goofy animated film from the '90s starring then-juggernaut child star Macaulay Culkin; perhaps its most intriguing element, however, has never seen the light of day.

The 1994 film tells the story of a socially awkward bookworm named Richard who visits the library one dark and stormy night. After a conversation with a mysterious librarian (Christopher Lloyd), the boy is soon swept into another world — turning into a fully animated cartoon character in the process. Along the way, Richard befriends three sentient books — Adventure, Horror and Fantasy — who help him along the way. During their adventure, the group encounter several famous literary characters, including Captain Ahab and Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. The film, while cornball in its delivery, is an enjoyable enough romp with some above average animation.

But not every one of the literary cameos in "Pagemaster" made it to the film's final cut. One example is a sequence with the heroes being menaced by the towering Frankenstein monster. Bits of the sequence have been salvaged from VHS promotional materials, proving the scene's existence if nothing else.

Still, the full Frankenstein sequence remains lost to this day, a prime example of content being cut from a film and slipping into obscurity due to a lack of proper archiving.

Roger Corman's Fantastic Four (1994)

After the cheesy Tim Story '00s films and the ill-fated 2015 Josh Trank reboot, you'd think the worst that could happen to the Fantastic Four is well known. But even before the dawn of the millennium, Marvel's first family was treated even worse, and the results were never meant to be seen — even if most people working on Roger Corman's "Fantastic Four" didn't know that.

Corman, a legend in inexpensive, fast moviemaking, was tasked by German producer Bernd Eichinger to assist him with a "Fantastic" adaptation. Eichinger had optioned the characters from Marvel in the early '80s for $250,000, but budgetary concerns in Hollywood's largely-pre-CGI age had left the studios uninterested. Eichinger's contract stated that his cameras had to be rolling by the end of 1992, so on December 28th of that year, production began on a shoot that lasted just under a month.

As documented in 2015's "Doomed: The Untold Story of Roger Corman's The Fantastic Four," despite some preliminary marketing and premiere date announcements, the film production was intended to further filibuster Eichinger's hold on the series rights, not make a film that would actually be ... you know, seen.

Stan Lee visited the set and mingled with stars Alex Hyde-White (Mr. Fantastic), Rebecca Staab (Invisible Woman), Jay Underwood (Human Torch) and Michael Bailey Smith (Ben Grimm), as well as Joseph Culp (Dr. Doom) and director Oley Sassone — but even back then, he was making promises that when Marvel could finally make their own movies, they'd do a much better job.

"['Fantastic Four'] is just about finished. It'll be released sometime, I think, at the end of this year," Lee said in August 1993. "I'm not expecting too much of it. It's the last movie to be made that we at Marvel had no control over. Our lawyers just gave the rights to Roger Corman to do the movie. There will be no other projects like that. Everything after that we're doing ourselves."

For years, the "Fantastic Four" was best viewed via Los Angeles video stores, which allowed patrons to take home a bootleg for free since it existed in a legal grey area, to say the least. Since then, it has come to reside on YouTube and feels like the Marvel equivalent of the "Star Wars Holiday Special," unlikely to ever get a proper release and bootlegged so frequently that it's doubtful anyone would ever pay for it. If you walk the halls of any comic convention, you are very likely to encounter a copy of this ill fated cosmic cash grab.

Mars Needs Moms: The Seth Green version

"Mars Needs Moms" is the rare example of a film that performed so poorly, it helped kill a sub-genre of animation. Not that it was the only cause, as the trend of motion capture animation had already been on the decline for some time.

The film follows Milo, a little boy tired of his mom's constant badgering and rules — simply wishing for a life without her. Unfortunately, Milo gets his wish, as his mother is whisked away by Martians to extract her "mom-ness" for their nanny bots. The film has an interesting premise, but is hindered by the uncanny valley nature of motion capture animation.

One strange aspect of the film's mo-cap involved Seth Green, who performed as Milo. Green, known for the "Austin Powers" movies and "Robot Chicken," had provided both the motions and dialogue for Milo, but only his motions were used. In his place, Seth Dusky (an actual child) became the voice of Milo.

For years, Green's audio work was suspected to be gone — and remained as such until 2020, thanks to a YouTube channel called Cinephile Studios. The creator of the channel had found Green's audio file in the most overlooked of places: the film's Blu-ray. By examining his Blu-ray's files, he had found a hidden audio file containing Green's voice.

The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

Released in 1928, "The Passion of Joan of Arc" was a cinematic adaptation of the real life trial of its namesake. Directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer, the film was a monumental success, and is still regarded as a top shelf cinematic classic.

The film's sets, as well as the presentation of its actors, was intended to be as realistic and gritty as possible. Unfortunately, as noted on the film's Criterion release, due to criticisms of the film's content by French nationalists, multiple cuts were made. The film was taken from Dreyer and re-edited per the order of the Archbishop of Paris and government censors. Following a fire at the UFA studios in Berlin, it seemed as though any remaining uncut prints of the film had been lost forever.

This became the general consensus, seemingly closing the book on "Joan" until the 1980s, when an intriguing discovery was made in the Dikemark Hospital mental institution. An employee, rifling through a janitorial closet, discovered a bevy of film canisters labeled under the film's title. Upon closer examination by the Norwegian film institute, it was determined that this indeed was Dreyer's original version. This monumental discovery allowed for the film to be remastered in full, allowing its place in film history, properly preserved once and for all.