That's What's Up: Who's Really Faster: The Flash Or Superman?

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: Now that we've seen them tearing it up on the big screen, what's the definitive answer to who's faster: Flash or Superman? — via email

This is one of those questions that's been asked over and over again—not just by fans, but in the comics themselves, and for good reason. If you have someone who's defined by being the best at everything, then it's natural to wonder what's going to happen when you stack him up against the guy who's supposed to be the best at one thing. The thing is, it kind of only happens on this level with those two. I mean, nobody ever asks if Superman's a better swimmer than Aquaman, or if he's better than Green Arrow at being a low-rent Batman. It's always just "who's faster?"

I think that has a lot to do with the fact that a race is something so easy to imagine, so deeply ingrained in culture from the day that the hare first laid down the challenge to the tortoise, and also lends itself to providing a definitive winner and loser—not that you'd know it from reading these comics. There are always shenanigans going on, which makes it tough to declare a real winner. Spoiler warning, though: it's the Flash.

Faster than a speeding bullet…

Don't get me wrong: Superman is fast—very fast. So fast, in fact, that if you go by the intro to the old TV and radio shows that first hit airwaves in 1945, it's the first thing you know about him. Before you know that he's strong, before you know that he spends his time soaring above skyscrapers, and before you ever hear words like "Clark Kent" or "strange visitor from another planet," you know that guy can outrun a bullet. Which, incidentally, means that he's at least capable of hitting 1,700 miles per hour from a dead stop in a fraction of a second.

And honestly? I love that about him. Whether or not they intended it to be so meaningful, or if Jackson Beck just thought it sounded better than starting off with "more powerful than a locomotive," they ended up with one of the most powerful images they could possibly have for explaining who Superman is and what he does. There are a lot of things that are fast enough to measure speed against, from race cars to airplanes, but a bullet has a very specific connotation, and it's one that would be as apparent for the audience that had just come through the Second World War as it is for us now. A bullet's not just fast, it's something that speeds towards its target for exactly one purpose: to kill it.

But Superman's faster. The first thing you know about him is that if it comes down to it, he can beat the bullet and stop it from hurting anyone, and that's kind of everything you need to know. The definitive image of Superman might be the one where he's soaring over the skies of Metropolis, but standing proudly between a hail of bullets and their intended victims is a pretty close second.

Beyond the catchphrase

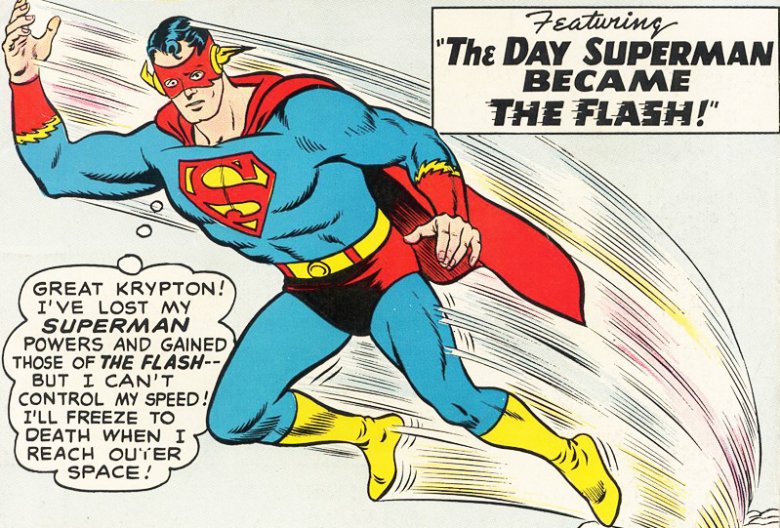

Even if we dismiss that catchy intro, though, there are still plenty of stories that highlight Superman's incredible speed. That dude used to fly through the time barrier under his own power so he could hang out with his friends a thousand years in the future, and he did that when he was a teenager. As an adult, he was even more powerful, although in this case, "more" was kind of an abstract concept.

By the height of the Silver Age, the creators behind Superman—led by Otto Binder, arguably the greatest comic book writer of all time and definitely the best Superman writer ever—had ramped up his powers to the point where they were pretty much limitless. Even the prefix, "super," became this weird kind of shorthand, not just for infinitely powerful, but for the specific kind of power that Superman and his cousin (and his dog, and his dad's monkey, and this one weird horse they hung out with) had. Complete invulnerability, incredible strength, and, of course, that super-speed we've been talking about.

Part of that is because the Silver Age Superman was the heir apparent to Captain Marvel (you know, the Shazam guy), who Binder had defined alongside artist C.C. Beck back in the '40s. In those stories, Cap was ridiculously, cartoonishly powerful, to the point where, in my personal favorite example, Dr. Sivana once blew him up with "a million tons of dynamite"—about the equivalent of your average thermonuclear warhead—causing him to land, scuffed up but otherwise unharmed, a few hundred yards away. Those stories were meant to challenge a man who was impossible to challenge, and figuring out how to put him through the wringer was part of the fun.

But the other part, and the more important one for our purposes, is that Superman was meant to be the absolute center of the universe. He was the fixed point around which everything else was built—not just the most important character but the most important thing in his world. Because of that, all of his abilities are taken to the superlative extreme: strongest, fastest, all-around best. He's not meant to be compared to anyone else, like, say, someone billed as the Fastest Man Alive, because he's not actually meant to be in their stories to begin with.

The trouble with a shared universe

That might seem like a weird statement when you consider that they're in a movie together that's based on a team they've been part of since 1960, but it has to do with the weird way that superheroes were created. The idea of a shared fictional universe on the scale that we see in comics is a relatively recent one, and it only really came about thanks to some weird business decisions.

In the Golden Age, after Superman debuted and people realized that there was a lot of money in telling stories about people who could punch out the moon, creators were figuring out what the rules of the superhero genre should be as they were creating it—and ignoring them most of the time anyway. Most of DC's major franchise characters were created then, and each one was meant to headline their own strip, and with it, to function as the center of their own little world. It wasn't long before someone figured out that you could probably make even more money by putting all the popular characters together in some kind of Justice Society, but still, each one had been created in isolation, meant to function as a character who could stand on their own, with their own setting and supporting cast.

Take World's Finest, for instance. Superman and Batman were both appearing in that comic for years before they ever appeared in the same story. Even after they had regular team-ups, the main characters would mostly be developed in their own books, completely separate from a wider world. They even had their own fictional cities to keep things from crossing over too much.

Compare that to the Marvel Universe, which, at the beginning, was largely created by a very small group of creators who were all working together in the same office. You wound up with a universe that was more cohesive, where Spider-Man spent the first issue of his own comic hanging out with the Fantastic Four, and where most of the characters lived within a 40-mile radius of each other. Neither one is inherently superior to the other—as the record will show, I like 'em both—but that isolationist approach means the characters develop differently, sometimes in very weird ways.

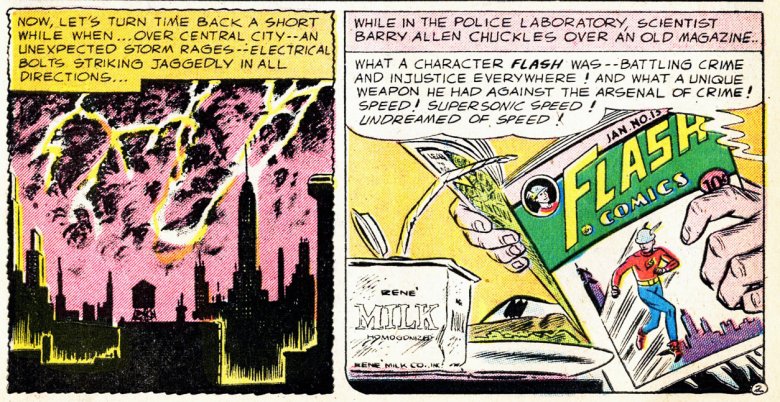

Like when Barry Allen showed up and decided to become the Flash because he read comic books about the Flash.

Barry Allen is fast enough to outrun intellectual property laws

If you didn't know about this, trust me: it's actually even more complicated than you think it is.

Point being, DC's books were built on a foundation that allowed creators to focus on variations on a theme, and Superman's theme was that he was the best at everything. There's even a story in Action Comics #314 where Jor-El sends a bunch of outer-space VHS tapes to Earth so that Superman can see what would happen if he'd landed on some other planet, and it turns out that even if he didn't have the same powers that he does here, he just would've become some other planet's version of Batman, Green Arrow, or Aquaman. Instead, he came here, and now he's just a guy who makes his friends watch his dad's weird video fanfic about how he'd be them on other planets.

That's why so many of the Flash and Superman's races against each other, the most obvious idea in the DC universe, have such screwy finishes. In Superman #199, they have a tie because they find out that gangsters are betting on the outcome, and nobody can profit if neither one actually wins. World's Finest #199 promises a race on the cover, but the story takes place in another dimension where neither one has powers, and there's no actual race, just a scene where they're both crawling towards the same thing and Flash gets there first. Flash #175? Another tie.

But that's also why the Flash has to win.

The fastest man alive

I think we can all agree that Superman has a lot going on, but while his stories were focused on being the best—a tactic that they shared with Silver Age Batman stories, which were less about murder clowns and more about how Batman is the greatest man who ever lived—other characters had the luxury of being a little more focused. And in the Flash's case, that focus was on speed—not just in terms of running fast, but as a concept.

That's how you get all the stories about time travel that have cropped up in The Flash over the years, all the way down to having entire seasons of a television show about them. Once you've done all the stories about, you know, running fast, you start to think about other ways to apply those powers, moving through all the different speed tricks, like vibrating walls, or creating tiny little tornadoes with your hands. Eventually, you get to the idea of being so fast that you could even stop yourself from making mistakes. Being able to run fast is one thing, but outrunning your own past? That's a super-power.

Of course, that might just be the same kind of happy accident that we got from the Superman intro. More likely, it's something that was inspired by a pulp writer's understanding of relativity and the idea that passing the speed of light could drop you into the timestream, something that's been pretty prevalent in pop culture for as long as we've used "Einstein" as a sarcastic slang term for "genius." Either way, it ends up with us having a ton of comics about a machine called the Cosmic Treadmill, which might be the single weirdest phrase that we've all just sort of accepted over the years.

Speed Kills

Flash stories are all about speed, in a way that Superman stories are never really about strength, or flight, or shooting heat beams out of your eyes. If Superman stories are about anything in that way, it's hope and inspiration, and while it's sometimes layered on so thick that it's easy to roll your eyes at it, there's no getting around it. It's the central metaphor of the character, and why he works so well.

So while the idea of a race might be an easy one to jump to as a creator, and an even easier one to sell to readers despite an ever-growing number of inconclusive fake-out endings, the only real way to end it is to have the Flash live up to his title. The simple truth is that Superman loses nothing if he's not the fastest man alive. The Flash, on the other hand, loses everything.

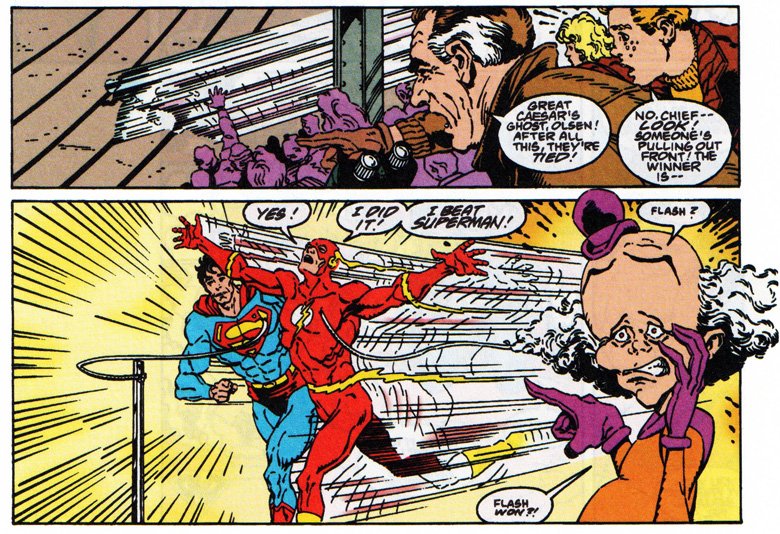

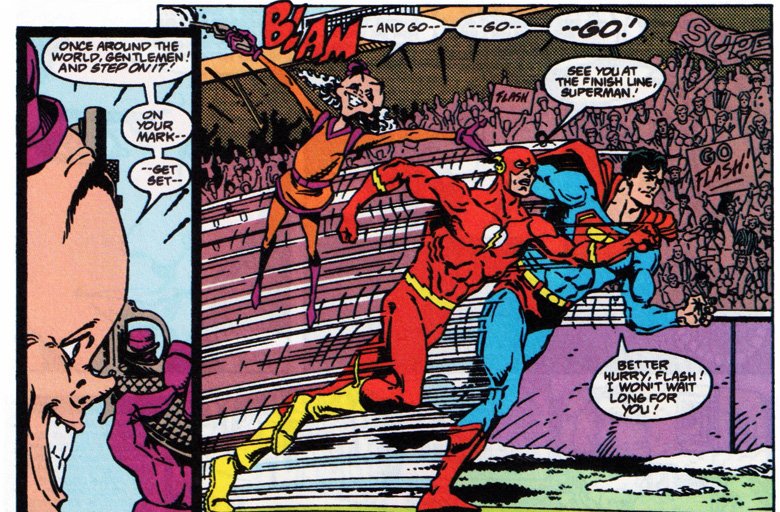

That's why one of my favorite Flash/Superman races is the one that Dan Jurgens and Art Thibert pulled off in The Adventures of Superman #463. The setup is that Mr. Mxyzptlk, the imp from the Fifth dimension who apparently swapped vowels for the ability to control reality itself on a whim, arranges a race between the two heroes. He doesn't even threaten them, he just literally talks so much smack that the Flash demands the race, and then it's on.

The Fast and the Furious: Metropolis Drift

It's worth noting that this particular race happened in 1990, when Superman was pretty far from the unlimited power of the Silver Age. At the time, DC was making a pretty concerted effort to stick to the idea that while he was still a guy who could jump to the moon on his lunch break, he was a little more vulnerable and a little less powerful than he had been. At the same time, the Flash in question was Wally West, former kid sidekick who took over the role after Barry died—by running himself to death, of course—in Crisis on Infinite Earths. Like Superman, he was being written as having some limitations that his predecessor didn't. Those little tweaks to the universe put them on somewhat even footing, especially with Mxyzptlk's rule that they both had to run.

I really love the idea that Superman's way better at flying than he is at propelling himself along the ground with his own two legs. I'm not sure why, but it's one of those little details that sticks out, and makes all those "who would win" arguments just a little more complicated, and a little more fun.

Anyway, Jurgens and Thibert build the race in a way that absolutely feels like it's going to hit one of those unsatisfying finishes. It turns out that while Mxyzptlk initially said he'd be zapped back to the Fifth Dimension if Superman won the race, he actually tied his fate to the Flash, who winds up winning and sending Mxy packing. Wally's initially disappointed, assuming that Superman found out and threw the race to beat the bad guy, but Superman confesses that he had no idea, and that Wally won fair and square.

It's a great moment for both characters, but it's not the best reason to bet on the Flash.

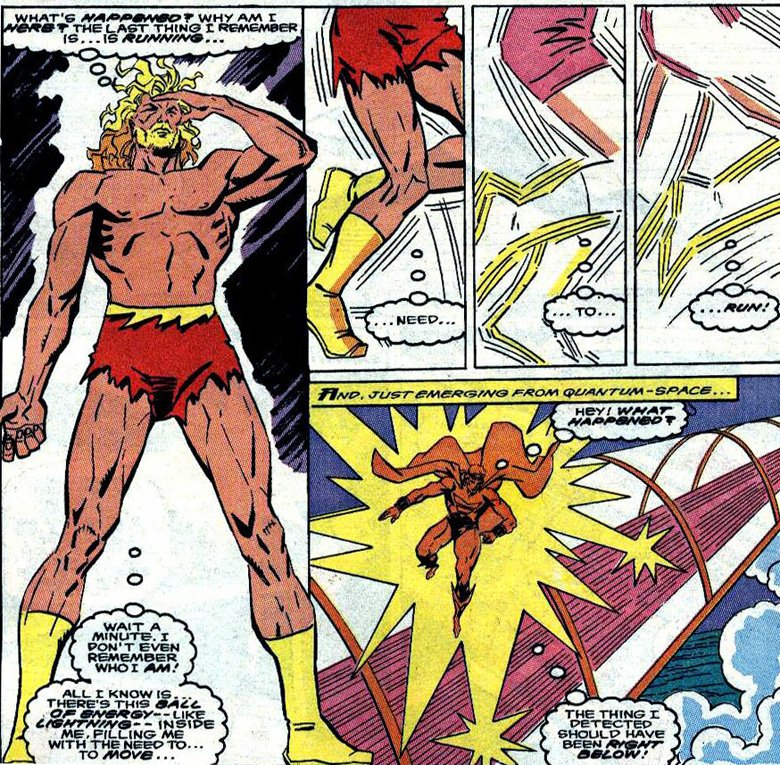

"Buried Alien"

Folks, meet "Buried Alien." He's the fastest man alive... in the Marvel Universe.

In Quasar #17, Mark Gruenwald staged a race between all of Marvel's speediest characters, including Quicksilver, Speed Demon, Captain Marvel, and Makkari, the Eternal who was once worshipped on Earth as Mercury, the god of speed. Most of the issue is concerned with Makkari overcoming an injury, regaining his confidence and pushing himself to the limit to live up to the one thing that defines him over the course of a race that lass 384,592 kilometers. One by one, he passes all of his opponents, finally believing in himself again... until a late addition to the race blows past him in an instant to win the whole thing.

That new racer is a refugee from another dimension, who appears, coalescing from vapor, in a torn red-and-yellow costume. He can't remember anything about his past except that his name sounds like "Buried Alien," and that being dubbed the Fastest Man Alive feels... right. He never did get his memory back, but he did stick around the cosmic side of the Marvel U under the name "Fastforward." Purely by coincidence, I'm sure, this story takes place three years after Barry Allen, the Flash, died in Crisis by running so fast that his body disintegrated.

Two things: first, it's worth mentioning that this story, like the entire run of Quasar, was written by Mark Gruenwald, who spent his entire career at Marvel but loved DC Comics so much that his magnum opus, Squadron Supreme, was essentially an alternate universe take on the Justice League. I don't want to ascribe motivations to a creator, but I suppose there's a chance that he might've wanted to rescue the Flash from his fate at the hands of the Anti-Monitor. Second, when Barry came back—because of course he came back, even if none of us actually wanted him to—it was by revealing that instead of being dissolved, his body had just merged with the extra-dimensional Speed Force, which tends to have the side effect of dropping people throughout time and space.

What I'm getting at here is this: Superman might be faster than a speeding bullet, but the Flash is so fast that he escaped the DC Universe and wound up in Marvel Comics. Let's see Superman do that.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."