The Untold Truth Of Ex Machina

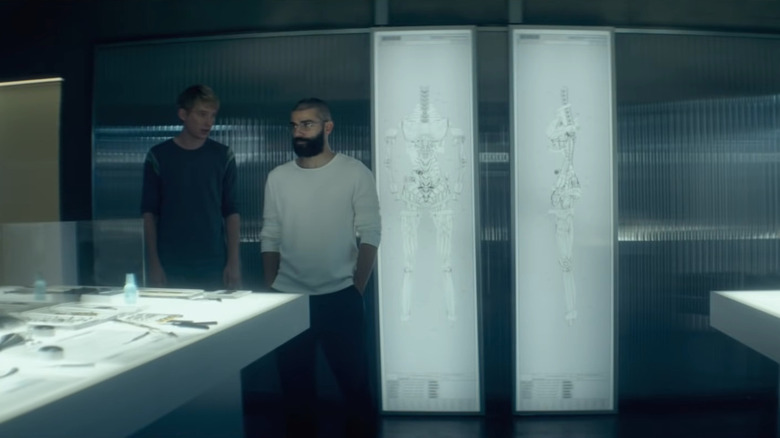

On the surface, Alex Garland's "Ex Machina" is a simple film. Nathan (Oscar Isaac) is a billionaire programmer and tech CEO who's created a humanoid robot named Ava (Alicia Vikander). One of Nathan's employees, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), wins a contest and is rewarded by getting to spend a week at Nathan's remote estate. When he arrives, he learns Nathan has a special plan for him: He's going to help perform a type of Turing test on Ava in order to determine her humanity.

With only four characters on screen (Sonoya Mizuno's Kyoko rounds out the cast), there's not much to get distracted by. The film is deceptively simple and only gets more complicated and eerie as it goes on. The characters' motivations are murky at best. Nathan has brought Caleb to his house ostensibly to perform the Turing test, but does he really need him? Ava wants Caleb to like her and perceive her as a "real" girl, but is she just manipulating him to escape Nathan's clutches? Does Caleb really care about Ava, or is he just projecting his own desires onto her?

We can't answer these questions for you, but what we can do is give you some insight into how this complex, profound film was made. With a wealth of pause-worthy moments and an ending that might require further explanation, there are bound to be plenty of behind-the-scenes secrets from the cast and crew. Keep reading to discover the untold truth of "Ex Machina."

How Alex Garland got the idea for Ex Machina

In a way, Alex Garland has been thinking about "Ex Machina" since he was just a boy. "The start of the movie is, I'm guessing kind of when I was 11 or 12," the director told The Et Cetera. His family got a home computer around this time, and he started learning how to code. "I would input programs that were kind of a Q&A, and this film traces itself back to that," Garland said, explaining how the idea of artificial intelligence first cropped up for him.

While these ideas ruminated in his mind for decades, he really began thinking about the film in earnest following a discussion he had with a friend. Garland told The Washington Post he has a neuroscientist buddy who thinks machines will never gain sentience. As Garland says, "His position is ... there's something specific about human consciousness that we don't understand but that when we do understand how it works, it will preclude the possibility of a sentient machine."

Garland was perplexed by his friend's position, so he started doing some reading on his own. After years of reading and thinking about the topic, Garland began to form his own opinion. "My suspicion has only gotten stronger that what my friend was saying is probably wrong." "Ex Machina" may not be a direct answer to this argument — it's not that didactic — but it certainly points us to Garland's own perspective on the issue.

No green screens were used

The technical elements of "Ex Machina" may seem highly advanced –- not to mention expensive –- but in actuality, everything is simpler than it might appear. The film had a meager budget of only $15 million, which meant producers had to be stingy with how they spent that money.

One of the most brilliant aspects of the film is its visual effects, which, despite its low-budget nature, actually garnered the film an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects in 2016. Amazingly enough, no green screens were used in the making of the film. Speaking with TechRadar, VFX supervisor Andrew Whitehurst explained why this was the case. Because the shoot was so short, Whitehurst said, "We were shooting between 15 and 25 set-ups every day." Setting up a green screen for every scene involving Ava would've extended the shooting time and bloated the budget.

The lack of green screen was also useful for the actors. "Because the film is made up of intimate scenes of dialogue between the characters," Whitehurst explained, "it was of the utmost importance that everyone on set could get into a groove, and it is my experience that as soon as you put a green screen up, everyone starts behaving a bit oddly."

Garland's inspirations for Ex Machina

Director Alex Garland looked to a number of different sources –- including television and film –- to find inspiration for his film. Garland told Esquire that along with reading a number of books relating to artificial intelligence and philosophy, he also turned to groundbreaking television to situate himself in the world of "Ex Machina." The film is mostly centered around two-person conversations, a simple dramatic structure that defined '70s movies like "Taxi Driver." Movies of that kind are rare these days, and instead, that dramatic form is found elsewhere. "'Taxi Driver' these days is 'Breaking Bad,'" Garland explained. "That's where you find it." Garland was inspired by this era of prestige television, which he saw as picking up the slack where film was lacking.

Garland didn't totally ignore other movies, however. One of his biggest influences was the dialogue-heavy 1980 sci-fi film "Altered States." The film follows a group of psychologists at a university who come to the conclusion that dreams are just as real as our waking reality. When they begin conducting a series of tests, a terrifying warping of reality begins to occur. Garland was also quick to point out the influence of Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey," due to its handling of artificial intelligence.

Garland had to fight to keep the film's title

The title of "Ex Machina" was incredibly important to director Alex Garland. "Ex Machina" comes from the phrase "deus ex machina," which translates to "god out of the machine." The origin of the phrase is ancient Greek and Roman dramas, which often included a god-like figure being lowered on stage via a crane (aka a "machine") in order to wrap up any conflicts. With the first part of the phrase removed, it translates simply to "from the machine" –- the god has been taken out of the equation.

While Garland was committed to this being the title of the film, not everyone else was on board. Speaking with The Film Stage, the director revealed that some people involved thought it was a bad idea because it isn't a well-known phrase and it's hard to pronounce. Incidentally, some of the producers were finally convinced to accept it following the success of another sci-fi film with a rather lofty title — Ridley Scott's "Prometheus." "They figured if they could make 'Prometheus' work, people would buy into 'Ex Machina,'" Garland explained.

While this was the evidence given for their change of heart, Garland thinks the real reason the title was accepted was much simpler. "If I'm being totally candid, the fact is that this is a really low-budget film and probably they just didn't care that much," he pointed out.

Ex Machina takes place in the very near future

"Ex Machina" comes off as very futuristic, but the actual time period in which it's set isn't really made clear. Speaking with IndieWire, Alex Garland came prepared with an answer to this puzzling question. "When someone would ask me, 'When is this taking place?' I'd say it's 10 minutes in the future," he explained. The obvious implication here is that the events of the film could theoretically happen today, but this also affected some of the film's technical elements.

Oscar Isaac's Nathan is a reclusive billionaire, which meant his house had to look nice but not overly futuristic, partly because the film doesn't actually take place in the future. The tech used in Nathan's house isn't all that advanced either. Nathan and Caleb use key cards to move around the house, something that seemed cool and tech-savvy to Garland at the time but isn't actually that high-tech. "Retrospectively, you're laughing because it's so stupid, and retrospectively, it's been pointed out to me, this is like the most lo-fi thing you could possibly do," he said.

Garland recalled when he first heard of this key card idea, nearly 20 years ago when he read about Bill Gates having a key card system in his house. While he thought it was futuristic at the time, he now realizes there's nothing that futuristic about it today. Luckily, the fact that "Ex Machina" is (almost) set contemporarily means these issues don't matter all that much.

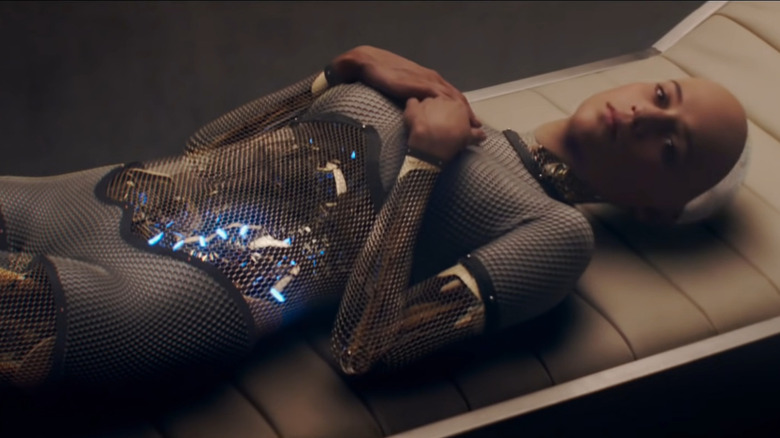

Ava was designed so she wouldn't look like other robots

Though "Ex Machina" had a relatively small budget, a lot of time and effort went into the film's design elements. One of the film's most important visual aspects was the design of Alicia Vikander's Ava. There have been so many iconic robots in film and television over the years, which meant Garland and the team had to figure out how to make Ava look unique.

Speaking with IndieWire, Garland explained how the design process began. "In a weird way, the first part of the design of Ava was finding out what she could not look like, rather than what she could look like," Garland said, adding, "Gold metal made you think of C3P0," which wasn't something they wanted to reference. A metallic chest immediately recalls the classic sci-fi film "Metropolis," while white plastic brings up Bjork's "All is Full of Love" music video or the Will Smith movie "I, Robot."

Ava is essentially supposed to be the first of her kind (apart from Nathan's previous prototypes of her), so Garland was adamant she not reference these other famous robots. "I didn't want people to start thinking about other movies with other robots. I want them to be attached to her, this robot," Garland said. For Vikander, Ava's unique look meant several hours in a hair and makeup chair every morning, but the effect is well worth it.

Alicia Vikander aimed for glitchy perfection when embodying Ava

Alicia Vikander wanted her performance to stand out from those of previous robot actors. A former dancer, Vikander approached the role from a physical standpoint first. As she began working out how Ava would move, she discovered a trick that was key to unlocking the character's physicality. "I realized when I aimed for that physical perfection, the way it just moved, that in a way made her more robotic," she told IndieWire. Ava — who's trying to convince Caleb that she is a girl — has an elegant, refined way about her that would be pleasing to look at if it weren't so suspiciously well-practiced.

Vikander went on to discuss what separates humans from robots in terms of their physicality and how this idea influenced her performance. "What is human is flaws and inconsistency," she explained. "So I gave her some offbeats. I wanted her to be a girl, but I also wanted her to have some glitches." It's these two converse aspects of Ava –- both her perfection and her glitches -– that illuminate her robotic nature while at the same time illustrating her desire to be seen as human.

Who inspired Oscar Isaac's performance?

Viewers might immediately think of god-like tech figures a la Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates when encountering the character of Nathan, but these weren't the people Oscar Isaac had in mind while he was working on the character. (Garland has said Nathan's company wasn't based on any big tech company in particular, but it could also stand in for any of them.) Instead, Isaac drew inspiration from two famous men who were god-like in their own right.

Speaking with /Film, Isaac said that his first inspiration was Bobby Fischer, a chess grandmaster and child prodigy. Isaac described Fischer as "so brilliant at this one thing, but also so angry and just so, towards the end of his life, full of hatred." Isaac's other inspiration was the director Stanely Kubrick, who Isaac called "the lighter side of that yin-yang."

The biggest influence Kubrick had on Nathan's character was his signature look. It was important to Isaac that Nathan wear glasses that looked similar to Kubrick's. Kubrick and Fischer's way of speaking was also an influence. "I listened to the way he spoke and Bobby Fischer, both of them are from New York," Isaac explained. It also mattered to him that both men were self-taught, meaning that they were both extremely intelligent savants but they also had some sort of self-made shrewdness about them, a characteristic Isaac brought to the character of Nathan.

Ava made her own Tinder account

The fictional storyline of "Ex Machina" is disturbing enough without any real-life elements thrown in, but that didn't stop the film's marketing team from trying to bring Ava into the real world. "Ex Machina" premiered at SXSW in Austin, Texas, and around this time, lucky residents of the city might've encountered Ava right on their phones.

As part of an advertising campaign for the film, the marketing team created a Tinder account for Ava to entice curious swipers, reported AdWeek. Tinder users were shown the profile of a 25-year-old woman named Ava (using images of Vikander herself), and if they matched with her, she would begin a conversation. Users came to realize it wasn't exactly a normal profile when she began asking questions like "have you ever been in love?" and "what makes you human?" Those familiar with the film might recognize these questions as the kind Ava asks Caleb in order to figure out how to act like a human herself.

If the Tinder user "passed" Ava's test, she would send them her Instagram handle, which is essentially an advertising account for the film. Whether or not the marketing campaign was cruel or hilarious is certainly up for debate, but Alex Garland told RogerEbert.com he had no idea the campaign was even happening and that he doesn't actually use social media himself.

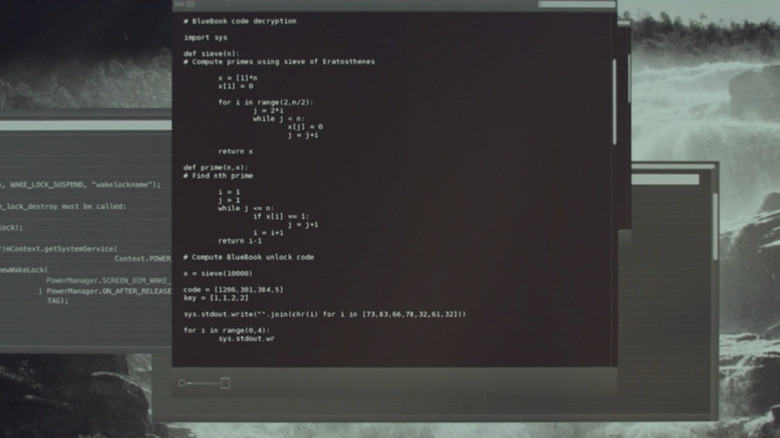

A hidden reference to one of Garland's favorite books

Nathan and Caleb frequently discuss philosophical texts in "Ex Machina," but one of the references made in the film is much more subtle –- it's buried in code, in fact. In the film's third act, Caleb gets Nathan drunk in order to find a way to free Ava. After stealing the key card to his room, Caleb sits down at his computer and goes through his code. Caleb starts to edit the code himself using an ancient algorithm called the Sieve of Eratosthenes.

The Easter egg in this scene isn't Caleb's use of this algorithm but what the code itself spells out. The algorithm produces a series of prime numbers that read as 9780199226559. According to Collider, those numbers happen to be the ISB number of a book by Murray Shanahan entitled "Embodiment and the Inner Life: Cognition and Consciousness in the Space of Possible Minds."

This reference is no accident –- Garland told Esquire that Shanahan's book was "epiphany-like" for him. Shanahan's book looks at the writings of mathematical philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein from a contemporary lens, arguing that metaphysical questions of machine vs. man aren't the questions we should be asking if robotic technology is to move forward. His philosophy, according to Garland, is to "just progress in a physicalist type way until you hit a brick wall." The wall in question may never even be reached, so in Shanahan's opinion, the possibilities for advancement are limitless.

Sound design was important in creating Ava

Every element of Ava's character — from her physical design to Alicia Vikander's haunting performance — contributes to her robotic embodiment. These elements are all visible to us, which, as Alex Garland told NPR, is exactly the point. "The trick of the film," he explained, "the way that the film intends to work is to present something which is unambiguously a machine and then gradually remove your sense of Ava being a machine, even while you continue to see her being that way."

While our eyes cue us into Ava's robotic nature fairly quickly, there's another facet of Ava's design that illustrates her machinery in a more subtle manner. A significant part of Ava's machine nature is revealed through sound design, Garland said. "You can hear ... the sounds of the bits of machinery moving, which aren't specified," he explained. It's not clear what exactly these sounds are, but it's obvious they represent some kind of machinery. A syncopated rhythm that sounds something like a heartbeat or a pulse can also be heard emanating from Ava, though it's not literally a heartbeat, of course.

This clever sound design ties together the thesis of Ava's character — she's human-like but also not human at all. There's some sense of the uncanny valley here that's impossible to look away from.

Alex Garland wanted to explore questions of gender construction

Speaking with Roger Ebert's Matt Fagerholm, Alex Garland explained that for him, the most interesting question posed in the film is "the question of where gender resides." Garland found himself pondering questions like "does gender reside in the mind, or does it reside in the external physical form?" Whether or not there is such a thing as a male or a female consciousness is also something Garland considered. He brought up the fact that you could put Ava's mind in a male-appearing body, and it wouldn't make a difference, except for in the way humans might perceive her (or him).

Garland went on to say, "It would be quite easy to construct an argument that Ava doesn't have a gender." However, he acknowledges we would struggle to take gender entirely out of the equation because of how she looks and how we perceive her. Indeed, the fact that Ava looks like a girl in her 20s makes the men in the film, as well as the viewers, ignore any interiority she might have because of the nature of female objectification. Her robotic presence is disruptive in more ways than one.