Writer Joe Hill Describes The Thrill Of Seeing The Black Phone Adapted For The Screen - Exclusive Interview

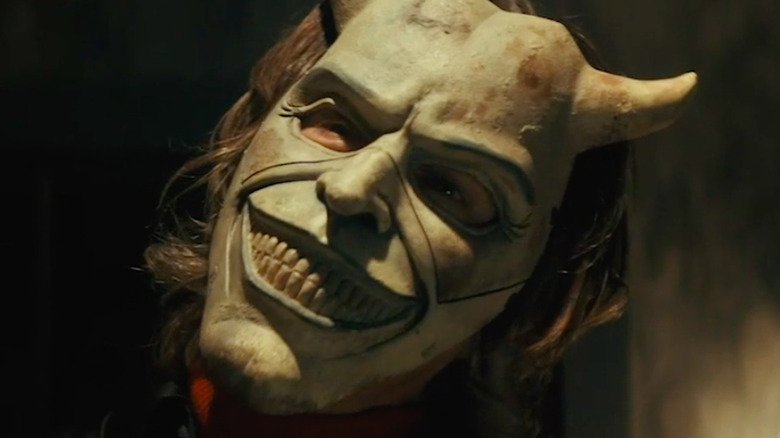

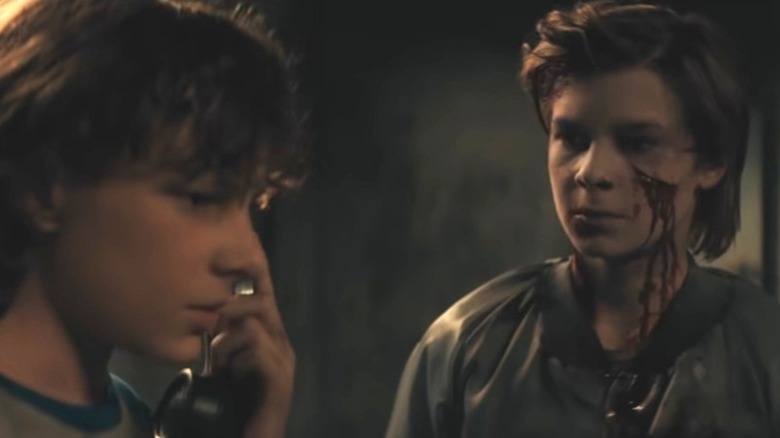

At this point in his career, writer Joe Hill is no stranger to seeing his work adapted to the screen. His comic book "Locke & Key," his novel "NOS4A2," and his novella "In the Tall Grass," which he co-wrote with his father, Stephen King, have all been the basis for recent TV shows and movies. The latest work from Hill's prolific career to get the big-screen treatment is his short story "The Black Phone." A deceptively simple tale about a kidnapped boy named Finney (Mason Thames) who gets calls from the killer's (Ethan Hawke) previous victims on a disconnected phone in the room where he's being held, the movie version of the story expands on Hill's original idea in ways the author found exciting and satisfying.

Looper sat down with Hill to discuss the movie adaptation of "The Black Phone," and Hill quickly made it clear that not only is he thrilled with what co-writer C. Robert Cargill and co-writer and director Scott Derrickson brought to the film, but he's also happy to see the story become more like the novel he always envisioned it to be. During our exclusive conversation, Hill discussed the roots of the idea for the short story, his feelings about what the filmmakers brought to "The Black Phone," and his gratitude for all the movie and TV adaptations of his work.

The Black Phone's roots in Hill's childhood

The cool thing about the adaptation of "The Black Phone" is that it's actually fairly faithful to your short story. How did you come up with this idea?

That's a good question, and I'm not sure I have an entirely satisfying answer, because you have to remember that I wrote the short story over 15 years ago. I was paid 35 pounds when it was published in an English horror magazine after it had been turned down by a bunch of magazines here in America. I was struggling to remember the genesis of the story, and it did strike me about six months ago. I grew up in Bangor, Maine, and I lived in an old, renovated Victorian, a big 19th-century house, and it had one of these crazy horror movie basements, where some of the floor's cement [and] some of the floor's dirt. And it had weird brick corridors, and you'd walk down them and get a spider web in your face, and dark corners with a boiler in one corner and a coal chute in another. There was a phone down there.

There was a phone in one of the rooms, a disconnected phone attached to one of the walls, and I remember even as a child thinking if that phone ever rang, I'd run screaming. So that has to be the genesis of the story. That has to be. The only thing is, did I remember that when I wrote the short story? Was that ever on my mind? I don't know if it was. It was so long ago that I can no longer [remember]. And you have to remember that I probably spent less than a month working on the story. I'm sure I wrote the first draft in 10 days. That's usually how long it takes.

Hill and the film's writers each brought something special

The film is incredibly faithful to the short story. Every line of dialogue in the short story is in the film. Every scene in the short story is in the film, but that's only like 40 minutes of the film. All together, that makes a 40-minute movie. So there's a lot more there. Everyone brought something to it that I think helped make it a really satisfying picture.

Scott Derrickson grew up in north Denver, in the dirty, violent 1970s, and a lot of the film's very autobiographical about what that was like, what it was like to be there, and it's sort of anti-nostalgia. I love that because I adore "Stranger Things." I think "Stranger Things" is a great show, but I'm not sure that the early '80s and late 1970s actually did look like a Spielberg movie all the time. The kids weren't actually mostly like Spielberg kids, precocious and clever and always quick with the witty line and stuff like that. It wasn't necessarily like that.

In the short story, The Grabber takes Finney to lock him into his basement with this disconnected antique phone. And then Finney gets calls from Bruce Yamada, the ghost of a friend who was killed by The Grabber months before. It's been a while since I read the short story, but I think that's the only ghost to call on the phone. What Cargill brought to it was all The Grabber's victims use that phone to call Finney, and they each have another suggestion for how he might escape. So Finney tries one thing, and that doesn't work. Finney tries another thing, and that doesn't work, but maybe the two things go together and might work. That's all Cargill. Cargill looked at the short story and said, "This is an escape room." The structure of this film is a great escape room. How does Finney get out? What clues does Finney need to solve? What puzzles does Finney need to solve to get out of that room?

So those are the three — the original short story, Cargill's escape room structure, and Scott Derrickson's very personal autobiographical stuff about childhood in the '70s — those are the three flavors that came together to make the frosted peanut butter cupcake that is "The Black Phone."

'It was one of the best scripts I had ever read'

What was your take on it when you heard what Scott Derrickson and Cargill were doing?

From the moment I read the first draft of the script, I was excited and thrilled and really hoped that the film would get made. I wasn't sure it would because lots of stuff gets developed. It's like, many are chosen and few are called. It was one of the best scripts I had ever read based on one of my stories. So in terms of what was on the page, I really hoped that it would get made.

When I worked on the short story, one thing I do know about the short story is the short story wanted to be a novel. I kept coming up with ideas for new scenes, new things that could happen, but I didn't have the confidence to attempt it as a novel. At the time that I wrote "The Black Phone," I was a failed novelist who had already written four books that I couldn't sell, that no one wanted.

I was locked into just writing short stories because I was afraid to commit months to writing a new novel and getting more rejection. I knew I could sell a short story. So every time it tried to become a novel, I fought that urge off and I insisted on keeping it 10,000 words, 9,000 words, keeping it tight.

What's really satisfying about the film is I get to see what the novel might have looked like, the best version. In 2004, I'm not sure I could have ever written it as well as what we got in the film, but it is satisfying 15 years later to get that novel-sized version of "The Black Phone."

Horror as a vehicle for exploring the terrors of childhood

The changes flesh out these characters in a way that's very interesting. It's a coming-of-age tale about a child who's learning how to be strong. Why do you think horror and fantasy are a good avenue for exploring children's coming of age, which is something you've done in other writing too?

Childhood is fearful. The dark under your bed, the dark in the basement is frightening. You hear about something. I remember when the hostages were taken in Iran in 1980, I was so disturbed by that, I felt sick to my stomach. Every time the story came up on the news, I had to leave the room. I was probably eight. I don't know how I thought it was going to affect me. I don't know what meaning that really had. I was just so profoundly disturbed by the thought that there were these people over in Iran who couldn't go home to their families and were being held at gunpoint. I was frightened by that profoundly.

As a child, you don't have any context. You haven't developed a sense of perspective about what's a reasonable threat to you and your loved ones, and what's terrible, but you can say, "Okay, but I can't do anything about this, and it doesn't pay to be twisted up in knots over it." You don't have that emotional armor yet.

I think that a lot of working through childhood is working through fear, coming to learn your own strength as a person and your ability to absorb the daily shocks of being alive. I'm not sure I've answered your question exactly, but I do think that if horror often dwells on a child or young protagonist, that's part of the reason. I was thinking "Locke & Key" too — the "Locke & Key" show also features teenage and child protagonists, although there's grownups in that story as well.

Hill feels 'fortunate' for all the screen adaptations of his work

Speaking of that, you've had quite a bit of your work, at this point, adapted to film and TV.

I've been very fortunate.

"Locke & Key" has been great. I'm still sad "NOS4A2" is gone.

Me too. I thought it was great. I thought Zach [Quinto] and Ashleigh [Cummings] were terrific. But the thing about "NOS4A2" is we got two seasons. We got to tell the whole story. The whole story of the novel winds up in the TV show, so there's really nothing to complain about.

Is there any adaptation that you've especially enjoyed?

I definitely think "The Black Phone" has been an experience that might never happen in my life again. Something like "The Black Phone" happens to a writer ... If it happens once in your life, you have been so incredibly lucky — not just that the movie has been a big success. It's been a hit, a theatrical hit in a day and age when that's less and less common, especially for a low-budget film.

But aside from how it did commercially, which is really exciting and everything, it's a really good movie. I knew from the moment I saw it. I thought, "This is so emotionally satisfying." Someone said it was like a satanic cross between "Silence of The Lambs" and "The Karate Kid," and I think there's some truth to that. It does have qualities of both films somehow braided together. It's great to have had something that feels like it's going to stick around [and] people are still going to care in 10 years.

"The Black Phone" is now available on digital, Blu-Ray, and DVD.

This interview has been edited for clarity.