Every Akira Kurosawa Movie Ranked Worst To Best

Ask any film student for the director they feel had the biggest influence on western cinema (or international cinema, for that matter), and you'll likely hear the name "Akira Kurosawa" a lot. There's a good reason for that — Kurosawa was a masterful storyteller whose influence is still seen in movies and television series decades after his death in 1998. His influence is found everywhere, from episodes of "The Mandalorian" to the works of Spielberg, Scorsese, Coppola, Kubrick, Lucas, and many others.

Kurasawa's inimitable style and embrace of epic storytelling set him apart from every other filmmaker working throughout the 20th century, and the man made a lot of excellent films. In addition to working as an assistant director and writer on numerous projects, he helmed some of Japan's most memorable period films. Kurosawa's work inspired a bunch of films in the west – so many that it's likely you've seen derivations of his work even if you've never sat down to watch one of his movies.

Because he was so influential and made some astounding films throughout his six decades in the business, it's difficult to determine a ranking of the whole lot. Even so, there's a general consensus about Kurosawa's filmography, and several of his more notable works stand out among the rest. These are all the films Kurosawa worked on as the director sorted from worst to best.

The Most Beautiful (1944)

Akira Kurosawa may be known in the west for his brilliant directing of epic films, but in his early days, he begrudgingly worked to support the Japanese war effort. "The Most Beautiful" is an example of a Japanese propaganda film made during World War II. The film wears its propaganda on its sleeve, and looking back at it with the knowledge of history makes it a fascinating example of the genre Japanese filmmakers were forced into during the conflict.

The film is set in an optics factory, where Japanese women work to complete their production targets to support the war. They sing songs about how amazing Japan is, work individually and as a group, and often exceed their production targets. Each day, the women pledge to do their part in the fight against the United States and Britain amidst a plethora of propaganda posters and the overwhelming sense of patriotism felt by each factory worker.

Ultimately, the message in "The Most Beautiful" is clear: sacrifice the self to support the Empire. This was only Kurosawa's second film as director, and he made it under the watchful eye of Japanese censors. The director created the movie as if he were a documentarian.

The Idiot (1951)

"The Idiot" is Akira Kurosawa's adaptation of Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel of the same name. Kurosawa wrote and directed the film, which came out at 265-minutes in length, though it was planned as a two-part movie. When the first cut didn't screen well, the larger version was edited down by the studio to 166 minutes, which is the release known to the world today. Incidentally, the 265-minute cut has been lost to history.

The film's plot follows that of the novel, though it's transposed into Japanese locations and within the culture. The eponymous character is Kameda, a man afflicted with what he calls "idiocy" and is, in reality, epileptic dementia. The story begins with Kameda traveling via ship from Okinawa to Hokkaido so he can get treatment for his affliction. When he gets there, he becomes involved in a love triangle with his best friend and a woman with a less-than-proper reputation.

Kurosawa's adaptation came from a place of love, as the director has been quoted as saying Dostoevsky was his favorite author. While "The Idiot" isn't the cinematic master's greatest work, it is a faithful adaptation, albeit truncated, of what Kurosawa intended.

Rhapsody in August (1991)

"Rhapsody in August" was Akira Kurosawa's penultimate film, released seven years before his death. The film is the only one in Kurosawa's filmography to feature a part made for an American actor. Richard Gere landed the enviable role of Clark, the nephew of Kane, a woman still grieving over the loss of her husband in the bombing of Nagasaki 50 years earlier. Clark visits his aunt to convince her to visit her brother, but there's a great deal of distrust stemming from the bombing that makes it difficult for Kane to reconcile the invitation to the United States.

The story is beautifully represented and shines a light on the pain and suffering many people felt decades after the war concluded. Gere plays his part brilliantly, but he's not the only fantastic actor in the film. A plethora of talent surrounds him via the inimitable Sachiko Murase (Kane) and Kurosawa's longtime collaborator, Hisashi Igawa. The film is incredibly moving and delves into emotions most modern viewers struggle to fully comprehend.

While it's not Kurosawa's best film, "Rhapsody in August" brilliantly illustrates his understanding of complex emotions and how he's able to bring them about through the performances of his talented cast.

Dreams (1990)

Akira Kurosawa was a talented screenwriter, but he hadn't put together a script by himself in over 40 years before he created "Dreams." The film is objectively beautiful in its depiction of the director's dreams, which inspired the film's creation. "Dreams" depicts eight mythic and unusual disparate short stories based on the director's dreams and nightmares, and they are interspersed with traditional Japanese folklore.

When Kurosawa was ready to make the movie, Japanese studios were unwilling to back him. Steven Spielberg and George Lucas came to Kurosawa's aid, convincing Warner Bros. to purchase the rights to the film. The American directors further helped Kurosawa by guaranteeing a ¥1.5 billion loan in Japan to cover production costs. Kurosawa, beloved in the west, was spurred by Japanese cinema following the release of "Dodes'ka-den" in 1970.

Lucas offered the assistance of Industrial Light and Magic to provide special effects work for "Dreams." This marked the first time Kurosawa used such technology in his movies, and the result is arguably gorgeous (per The Washington Post). "Dreams" didn't capture the same level of attention as some of his earlier work, but it stands as a lasting legacy of the man's glorious vision.

Dodes'ka-den (1970)

When Akira Kurosawa made "Dodes'ka-den," it was the straw that broke the camel's back in terms of the director's acceptance among his peers in Japan. The movie went over the heads of Japanese audiences, and it did not do well financially. The film cost ¥100 million ($5.6 million in 1970) and was the director's first color feature. Kurosawa mortgaged his home to finance it, but this left him indebted, in poor health, and unable to secure funding for future projects. He couldn't find work in Japan, and in December 1971, he attempted suicide by cutting his wrists.

That's a terrible outcome from what is arguably a lovely movie. "Dodes'ka-den" is based on Shūgorō Yamamoto's novel "A City Without Seasons." It tells the tale of a group of homeless people trying to survive in a shantytown on the outskirts of Tokyo, Japan. It is told in a series of overlapping vignettes focusing on the film's many characters. The movie's title is an onomatopoeia representing the sound a trolley car makes while running. Despite killing Kurosawa's career in Japan, the international market loved "Dodes'ka-den." It was nominated for Best Foreign Film at the 44th Academy Awards.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Sanshiro Sugata (1943)

"Sanshiro Sugata" is Akira Kurosawa's directorial debut based on Tsuneo Tomita's novel "Sugata Sanshirō." The film is a martial arts drama centered around a young man named Sanshiro who travels to the city to learn the art of Jujitsu. When he arrives, he's surprised to learn of the existence of a new martial art system called Judo, which he embraces. The film delves into numerous themes, including education, devotion, and dedication to one's craft.

Despite being created under the watchful eyes of the Japanese wartime entertainment ministry and its censors, the film is not a propaganda picture. Kurosawa was eager to direct the movie before he'd had a chance to read the novel it's based upon. Once he read it, he wrote the screenplay, but Kurosawa had to contend with the censor board, which he equated to putting the film on trial. Because it was a period piece, the censors allowed Kurosawa to release the movie, but only after cutting 1,845 feet of footage.

Much of those scenes have since been recovered and included in the 2002 DVD of the movie. According to The Japan Times, most of the cut footage was saved by the Russian State film archive, Gosfilmofond.

The Quiet Duel (1949)

"The Quiet Duel" is an introspective film centered around Dr. Kyoji Fujisaki. While working as a physician for the Japanese army during World War II, Dr. Fujisaki contracts syphilis. He did so by accidentally cutting himself during an operation, resulting in the transmission of the disease from the patient. Despite how he was infected, syphilis was considered a shameful affliction, which was all but incurable at the time. After returning home from the war, he again meets the patient who infected him.

This chance meeting shows Dr. Fujisaki what may befall him should he not treat the disease. At the same time, he's overcome with guilt over not being able to help his patient and begins to treat himself with antimicrobial medication. He then rejects his fiancé, Misao, to spare her the shame of their union as he attempts to cure himself. It's a sad tale, to be sure, and it ends with Dr. Fujisaki doubling down on his rejection of Misao.

"The Quiet Duel" wasn't a successful film, which Kurosawa discussed in his autobiography. "I think the problem with 'The Quiet Duel' was that I myself had not thoroughly digested my ideas, nor did I express them in the best possible way" (via Akira Kurosawa).

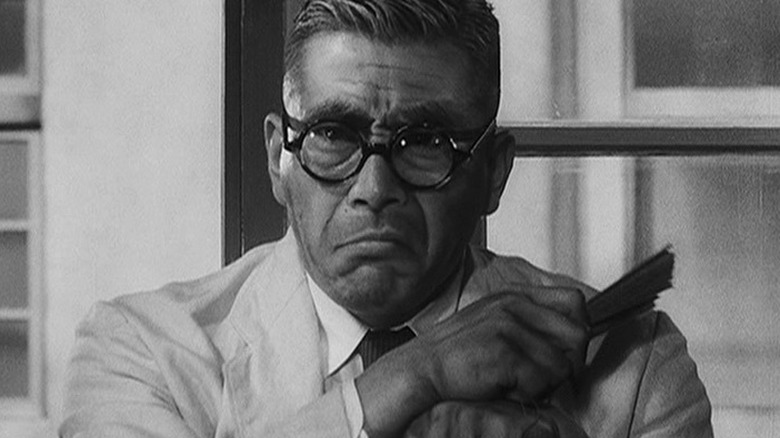

I Live in Fear (1955)

"I Live in Fear" teams Akira Kurosawa with his longtime collaborators, Toshirô Mifune and Takashi Shimura, in a story about a factory owner stricken with fear over a nuclear attack. To avoid the impending doom, he begins a plan to move his family to a farm in Brazil. Mifune plays the maddened factory owner, Kiichi Nakajima, and he plays the role to absolute perfection, as he depicts a palpable fear that must have been felt by many Japanese people following the nuclear attacks during WWII.

The film is best described by Criterion, which writes, "With this mournful film, the director depicts a society emerging from the shadows but still terrorized by memories of the past and anxieties for the future." The movie was made only a decade after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when those traumatic events were still at the forefront of Japan's national psyche. You can feel that pain in every scene featuring Mifune's descent into paranoid madness.

Kurosawa employed a three-camera method with the film, which gives it somewhat of a documentary feel. The characters are often shot from behind, which helps place the viewer inside the scene in a way Kurosawa hadn't done prior to "I Live in Fear."

Dersu Uzala (1975)

"Dersu Uzala" was made at an important time in film history, as it is one of the many movies and books that inspired George Lucas' "Star Wars." More specifically, "Dersu Uzala" heavily influenced "The Empire Strikes Back." While Kurosawa's films influenced several western directors, those two films are inexorably linked, though few "Star Wars" fans know their similarities. "Dersu Uzala's" influence on "Star Wars" is enough to give it a solid place in film history, but it stands on its own as one of Kurasawa's best semi-nonfiction films.

The film is based on Vladimir Arsenyev's memoir of the same name, which tells the story of a Russian trapper during the exploration of the Sikhote-Alin region of the country. It was described in The Guardian as an "elegiac film of great visual and spiritual beauty about the relationship between an intelligent European raised in an advanced urban world (the tall, handsome Yuri Solomin), and a wise, nomadic Asian in close touch with the wilderness (the stocky, elderly Maxim Munzuk)."

"Dersu Uzala" was made in cooperation with the Soviets and is Kurosawa's only film that isn't in Japanese. The film did well upon release in the USSR and Europe. It was the first film Kurosawa directed after his attempted suicide, making it incredibly important as it revitalized his career.

The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail (1945)

After World War II ended, filmmakers like Kurosawa found themselves in blessed yet unfamiliar territory. The Americans came through and got rid of all the government censors — or at least their unquestionable power as such — ensuring Kurosawa could make the movies he wanted to without a bunch of shortsighted overbearing government censors. The first film he made during this time was "The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail," but things didn't go according to plan.

While the censors no longer had the power they did before the war, Kurosawa was nonetheless required to come before them and present his film. He was told his script was worthless, but Kurosawa didn't care, as they no longer had legal authority. Still, "The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail" was filmed without approval, and it wouldn't make it into Japanese theaters for seven years. The movie is one of Kurosawa's period pieces and is set in the late 12th century.

It centers around Yoshitsune Minamoto, a Japanese general who returns from a naval battle to face arrest. He escapes Kyoto with six of his loyal samurai warriors, who then have to disguise themselves as monks to cross the border. The film is considerably short for a Kurasawa picture, clocking in at only 59 minutes.

Red Beard (1965)

"Red Beard" brought Akira Kurosawa and Toshirô Mifune together for the last time, ending a working relationship that included 16 films over the course of 17 years. The film is based on "Akahige Shinryōtan," a short story collection from Shūgorō Yamamoto, which Kurosawa co-wrote into a screenplay. The film is set toward the end of the Tokugawa period of the late 19th century, where a grizzled old doctor nicknamed "Red Beard" (Mifune) works alongside a rookie physician played by Yuzo Kayama.

Kurosawa delved into a familiar favorite of his, Fyodor Dostoevsky, by incorporating elements of his novel "Humiliated and Insulted" into the film. The story plays like a Victorian novel set in Japan, featuring all the beauty and charm you'd expect to find in a three-hour epic tale. The making of the film drove a wedge in the relationship between the director and his star, ensuring they would never again work together.

The film was Kurosawa's final black-and-white project and was nominated for several awards, winning many. "Red Beard" was nominated for best foreign language film at the Golden Globes, and it did well financially in and out of Japan.

The Lower Depths (1957)

"The Lower Depths" is based on a play of the same name by Maxim Gorky, but instead of centering the story in Russia, it's transposed into Japan. The story revolves around a rundown tenement building kept by an older couple that lets out rooms to the poor and indigent. Everyone staying there is either a prostitute, thief, gambler, or drunk, though there is a Buddhist pilgrim named Kahei who arouses a great deal of suspicion. Like many of Kurosawa's films, "The Lower Depths" examines the human narrative through archetypal representations.

In the case of "The Lower Depths," Kurosawa explores the nuances between nihilism and existentialism through the lens of Kahei and Yoshisaburo, the gambler. The director manages to capture the play's theatrical narrative via a multi-camera setup that naturally frames the story. "The Lower Depths" is rich with Japanese customs unfamiliar to the west, but this doesn't detract from the movie's message, which is perfectly summed up in the unusual ending that mixes comic undertones with the serious emotional reality of the characters.

"The Lower Depths" didn't perform as well as some of Kurosawa's other films set in the Edo period. Regardless, According to Kinema Junpo, it's one of The Greatest Japanese Films of All Time.

Scandal (1950)

Akira Kurosawa had a negative relationship with the press and government throughout his early career. He worked on numerous propaganda films during WWII, and his projects were often stifled by censors who didn't understand or misinterpreted his work as being too similar to western values. "Scandal" was the culmination of the director's many frustrations that plagued him throughout his first two decades as a filmmaker.

Kurosawa described "Scandal" as a "protest film," saying, "it was directly connected with the rise of the press in Japan and its habitual confusion of freedom with license. Personal privacy is never respected, and the scandal sheets are the worst offenders." Watching the film, it's clear Kurosawa doesn't like the press, and this extends beyond his creativity, as he rarely gave interviews or cooperated with the media in any way.

"Scandal" tells the story of an artist and a classical singer who meet in the mountains. When they depart for the hotel they're staying at, paparazzi hound them. When the photographers are rebuffed, they plot vengeance by taking the singer's picture on their terms and accompanying it with a fake story titled "The Love Story of Miyako Saijo." The ensuing scandal gives the film its title, and as you may imagine, it is unkind to the press.

Madadayo (1993)

"Madadayo" is Akira Kurosawa's 30th and final film completed by the director before he died in 1998. The film is set before the outbreak of WWII and details the life of Hyakken Uchida, a writer, and professor at the end of his career. Like many of Kurosawa's films, "Madadayo" focuses on the personal relationships of a large group of people, all of whom are centered around the professor's former students. The story is told in Kurosawa's preference for vignettes, most of which were taken from Uchida's writing.

One of the underlying themes explored in the film is the American occupation of Japan after the end of WWII and how it impacted Japanese culture and society. In many ways, "Madadayo" was made for the Japanese people, but Kurosawa found that it was loved in the west.

In an interview with fellow director Nagisa Oshima, Kurosawa was asked how his style fit in a post-WWII culture, and he replied, "I didn't know why, but people responded to my films. I found it puzzling. In the case of 'Madadayo,' for example, I thought people overseas wouldn't understand it, but it got a great response. [...] They understand some parts of it better than the Japanese audience."

One Wonderful Sunday (1947)

"One Wonderful Sunday" is another film Akira Kurosawa made dealing with the post-WWII American occupation of Japan. The film revolves around Yuzo and his fiancée, Masako, an unwealthy couple who comes together every Sunday for their weekly date. Their only problem is that they have ¥35 between them ($3.19 in 2022). They repeatedly find that their lack of funds stands in the way of renting an apartment so they can live together, they can't enter a club because they look too poor, and they can't afford tickets to the symphony.

By all accounts, the first act plays out antithetically to the title, but the couple manages to make the best of their day together. They act out the things they wish they could do if they only had the money. The tone of the film shifts as it emphasizes poverty amidst the societal decay of a languishing Japanese post-war culture.

Kurosawa's ability to portray two lovers with nothing but the love they have for one another and the future they both dream of is masterful storytelling. The director focused on failure and an enduring need never to give up no matter the situation.

Sanshiro Sugata Part II (1945)

If there's one thing Akira Kurosawa didn't often do, it was sequels. It's not something the director was interested in, but in 1945, he created the sequel to "Sanshiro Sugata" despite not wanting to. Kurosawa explained that "This film did not interest me in the slightest. I had already done it once. This was just warmed-over." While the director wasn't excited about the project, the film is superior to its predecessor, accomplishing much that the original didn't.

"Sanshiro Sugata Part II" was filmed toward the end of WWII, and unlike its predecessor, parts of the movie consist of propaganda. As in the first film, a martial arts student strives to become a Judo master while working under the tutelage of the discipline's founder. The underlying subplot pits the Judo, and Karate masters against one another in an enduring rivalry as the main character improves his skills, fights his opponents, and achieves his goal.

The primary opponent is an American boxer, and this is where Japanese propaganda comes into play. The film promotes the superiority of Judo over boxing, which establishes a rivalrous tone throughout the film that wasn't present in the first "Sanshiro Sugata" film.

Kagemusha (1980)

"Star Wars" was influenced by numerous films and stories that preceded it. George Lucas' many influences include works by Kurosawa, but he isn't the only director in the franchise to find inspiration in the Japanese director's filmography. J.J. Abrams was heavily influenced by "Kagemusha" while developing "The Force Awakens," and Rian Johnson's "The Last Jedi" also takes a great deal of inspiration from Kurasawa's 1980 epic.

The film is set during the Sengoku period when a criminal is chosen to double for the aging daimyō, Takeda Shingen. This was done to ensure the clan remained safe from its enemies during a particularly vulnerable period. The title, "Kagemusha," translates to "Shadow Warrior" in English, but it's also a term in Japanese for a political decoy. Kurosawa's longtime collaborator Tatsuya Nakadai plays Shingen, and the Kagemusha is recruited to replace him in one of the veteran actor's greatest performances.

"Kagemusha" is one of Kurosawa's greatest epics. Roger Ebert gave it four stars, calling the film "simple, bold, and colorful on the surface, but very thoughtful. Kurosawa seems to be saying that great human endeavors (in this case, samurai wars) depend entirely on large numbers of men sharing the same fantasies or beliefs."

Drunken Angel (1948)

Akira Kurosawa worked with Toshirô Mifune on 16 films, many of which are considered the director's best. That relationship began with the production of "Drunken Angel," which sees Mifune play a member of the Yakuza named Matsunaga. Takashi Shimura, another of the director's preferred actors, plays an alcoholic doctor named Sanada, the eponymous character referenced in the title. The two meet when Matsunaga requires treatment for tuberculosis, which he initially refuses, preferring to leave his disease untreated.

The two become friends of sorts, but when Matsunaga's boss is released from prison, he finds himself on the outs with the Yakuza and abandons his treatment. This leads to a confrontation that leaves Sanada angry at his friend, believing he threw his life away when he could have been cured. Ultimately, the doctor shifts his focus to his other patients, closing out Mastunaga's story with a positive note about a young woman who defeated the disease.

Kurosawa had difficulty navigating the strict censorship laws with "Drunken Angel." His usual foes in the Japanese ministry were replaced with American occupation censors directed by the U.S. government. Despite this, Kurosawa said, "In this picture, I finally discovered myself. It was my picture: I was doing it and no one else."

No Regrets for Our Youth (1946)

In "No Regrets for Our Youth," Akira Kurosawa explored the cultural impact of the Kyoto University incident. The event centered around a law professor, Takigawa Yukitoki, who spoke about the criminal justice system's need to understand the underlying cause in a person's background to render judgment against them correctly. His ideals were labeled "Marxist," and his words sparked a movement that resulted in his termination. "No Regrets for Our Youth" takes place immediately after the Kyoto University event in 1933.

The film centers around Yukie Yagihara, a young woman living in ignorance of the political upheaval sweeping across Japan as the nation invades Manchuria. Things change when her father is forced from his university position for espousing anti-fascist views to his students. As the reality of Japan's situation dawns on her, she finds herself falling in love with one of her father's students.

His radical ideology mirrors Yukie's father's, ensuring both will find trouble in the Japanese government's drive to flush out and suppress anti-fascists throughout the country. The film features the only female protagonist in Kurosawa's filmography, and Setsuko Hara's performance as Yukie is brilliant and establishes this narrative outlier as one of Kurosawa's best female characterizations.

Stray Dog (1949)

When "Stray Dog" was made in post-WWII Japan, it was an early entry in the film noir crime genre, growing in popularity elsewhere in the world. The film pairs two police officers with vastly different personalities, making it one of the earliest examples of the buddy cop genre. Criterion describes the movie as "A bad day gets worse for young detective Murakami," which is apt, seeing as the young officer's day begins when a pickpocket steals his Colt revolver while he's on a crowded bus.

Before long, the weapon is used in a mugging, resulting in the theft of ¥40,000 (around $3,600 in 2022 when converted and adjusted for inflation) from the victim. To recover his pistol, the detective goes undercover, desperately searching for the so-called "stray dog" who took the weapon. Murakami's desperation leads him close to crossing the line, but he's held back by a veteran police officer, Chief Detective Sato. The film has been called Kurosawa's first masterpiece, though the director thought it was too technical and disparaged it on several occasions.

Years later, Kurosawa wrote in his memoir about "Stray Dog," indicating that he'd changed his mind about the film. The movie has been called Kurosawa's coming-of-age picture, and it came the year before his international breakthrough, "Rashomon."

Throne of Blood (1957)

Akira Kurosawa took inspiration from numerous sources, including Russian novelists and various playwrights. "Throne of Blood" is the director's take on William Shakespeare's "Macbeth," depicting the events within a Japanese setting with a focus on a samurai warrior, General Washizu (Toshirô Mifune). When a spirit visits the general, he's told that he'll become the ruler of Spider's Web Castle. After sharing the prophecy with his wife Asaji, events play out much as they do in "Macbeth," with Asaji encouraging Washizu to ensure the prediction comes to fruition.

After taking her advice, Washizu, who was previously devoted to his lord, murders him so he can take his place. The events continue to play out as they do in the play, and the inevitable conclusion is fraught with peril and as bloody as it is in "Macbeth." Incidentally, despite being transposed to Japan, "Throne of Blood" is celebrated as one of the best film adaptations of Shakespeare's play. That's saying something, seeing as "Macbeth" has been adapted to death over the years.

Derek Malcolm called the film "a landmark of visual strength, permeated by a particularly Japanese sensibility, and is possibly the finest Shakespearean adaptation ever committed to the screen."

Yojimbo (1961)

"Yojimbo" is an Akira Kurasawa classic you may recognize even if you've never seen the movie. That's because Hollywood really likes remaking the film, and several excellent adaptations have been produced in the west. "A Fistfull of Dollars" is probably the best example, despite resulting in a conflict between Kurosawa and Sergio Leone over the unauthorized adaptation. Kurosawa's film opens with Kuwabatake Sanjuro, a wandering rōnin arriving in a small town.

He stops at a farmhouse to drink some water and overhears the farmer speaking to his wife about the fate of their son. The boy wants to join one of the two gangs vying for control of the town. Eventually, Sanjuro walks to town, where he quickly surmises the two sides of the conflict. Playing both sides, Sanjuro agrees to work as a bodyguard.

His skills are evident after he deftly dispatches three men in mere seconds. The conflict escalates, with Sanjuro playing each side to his advantage, ultimately confronting and taking out all of the major players. The one man he spares is the son of the farmer he met at the story's beginning, repaying the kindness he received by letting him live.

Ran (1985)

"Ran" is the third of Akira Kurosawa's adaptations of William Shakespeare's work. The film adapts "King Lear" as an epic historical piece set in Japan's Sengoku period. Initially, Kurosawa didn't use The Bard's work for inspiration and came to it as production commenced. Despite this, the story remains true to the themes of the source while it's transposed to a Japanese setting. Kurosawa incorporated cultural elements of Japan into the narrative, including tales of Mōri Motonari, a daimyō known as the" Beggar Prince."

The film is about an aging warlord who decides to abdicate his lands to his three sons. He chooses to split up his lands evenly, but after his youngest son warns of potential betrayal, he banishes him in favor of his eldest sons. This ultimately results in the young man's prediction coming true. The film is an absolute epic portrayal of Shakespeare's play, with the role of Lady Kaede taking center stage throughout much of the picture.

"Ran" has been hailed as Kurosawa's final masterpiece, and it stands as one of his greatest films. It features an intensely shot and beautifully choreographed final battle scene that sets "Ran" apart from every epic in Kurosawa's filmography.

High and Low (1963)

"High and Low" is one of Akira Kurosawa's police procedural films. The director loosely based it on Ed McBain's novel "King's Ransom" and features Toshirô Mifune in the lead role as Kingo Gondo. As an executive at National Shoes, Gondo mortgages everything he owns to purchase a controlling interest, but things hit a snag. Just as he's about to take over the company, his son is kidnapped and ransomed for a large sum of money.

In actuality, the kidnappers messed up and took the wrong child, but that doesn't change their ransom demands. Gondo is stuck in another desperate situation — should he pay the ransom to save the boy or use the money to save himself and his family from financial ruin? Ultimately, he chooses the former, but at a cost. The film shifts into a police detective drama as the hunt for the kidnappers transforms into a trap that flushes out the evildoer.

"High and Low" was heavily praised upon release. Kieth Phipps described the film, writing, "While not a masterpiece on par with Kurosawa's best work, High And Low is a fine example of his craft and further proof that it's not a few masterpieces but the overall scope of a career that defines a great director."

The Hidden Fortress (1958)

"The Hidden Fortress" is considered to be one of Kurosawa's masterpieces, and it is another of his films that heavily influenced the development of "Star Wars." Of course, its influence can be found outside George Lucas' franchise, but that is arguably the most significant example. The film centers around two peasants who agree to escort a couple across enemy lines in return for gold. What they don't realize is that the man and woman are General Makabe Rokurōta and Princess Yuki.

The general initially wanted to kill the peasants but changed his mind when he learned of their plan to escape the territory held by the Yamana clan. The peasants, Matashichi and Tahei, create numerous problems that make their transit a bit rockier than the general would like. Eventually, the group is captured by Tamana forces. However, the peasants manage to avoid this fate, even going so far as to try and score a reward for their companions' capture.

"The Hidden Fortress" is an early example of an epic tale involving characters on a road of self-discovery who stumble into problems along the way. Kurosawa manages to balance the comedic aspects of Matashichi and Tahei with their overt greed, ultimately rewarding them at the end of the film.

Rashomon (1950)

Before 1950, Akira Kurosawa wasn't well-known in the west. That changed with "Rashomon," a film that effectively opened up Japanese cinema to the rest of the world. The film is notable for being the first Japanese feature film to receive international attention. It won numerous awards, including the academy honorary award at the 24th Academy Awards two years later. The film stars Toshirô Mifune as Tajōmaru, the bandit opposite Takashi Shimura's Kikori, the warrior. "Rashomon" is based on Ryunosuke Akutagawa's short stories "In a Grove" and "Rashōmon," featuring many of the key elements found in both works.

The film features a central plot involving the murder of a samurai warrior in a forest, as told from different points of view. Each retelling of the murder is subjective and framed to make the one telling the story to appear honorable. Of course, each of them is lying, offering a contradictory exposition of the murder, which leaves the audience guessing throughout "Rashomon."

The film has a lasting legacy and influenced Ridley Scott's "The Last Duel," Rian Johnson's "The Last Jedi," and many more. Steven Spielberg's Amblin Entertainment is developing it as a ten-episode series for HBO Max.

Sanjurō (1962)

Yojimbo proved to be an incredibly popular movie, which influenced his subsequent picture, "Sanjurō." The film is an adaptation of Shūgorō Yamamoto's short story "Peaceful Days," but following "Yojimbo's" success, the narrative was altered to include the lead character in "Sanjurō." In this film, Toshirô Mifune's rōnin, still going by the surname of Sanjurō, works with a group of young warriors to find and quash their clan's evil influences.

One of the film's themes is the negativity of rushing to violence. At one point in the story, Sanjurō is criticized for killing too often and is told, "You're like a sword without a sheath. You cut well, but the best sword is kept in its sheath." The film pits Sanjurō against a man very much like himself. Hanbei Muroto (Tatsuya Nakadai) is an outsider, but his motives differ from Sanjurō's, putting the two at odds.

In the final confrontation, Sanjurō's speed aids in his victory, but it's bitter. As the young group of samurai bow to him, he scolds them, saying he'll kill them if they follow his lead. It's a brilliant summation of the character. The film's events build upon "Yojimbo" to make Sanjurō a far more compelling character.

The Bad Sleep Well (1960)

Akira Kurosawa adapted three of The Bard's works into film, and his second, "The Bad Sleep Well," takes a great deal of inspiration from "Hamlet." Outside of Shakespeare's influence, Kurosawa used his nephew, Yoshio Inoue's, story "Bad Men's Prosperity" to structure the narrative. The story is centered on a young businessman, Kōichi Nishi (Toshirô Mifune), who is determined to expose the men responsible for his father's death after he allegedly falls to his death from an office window.

To do this, he takes a job at a company overburdened with corruption. He also marries the daughter of the company's vice president, all the while climbing the social ladder. At the wedding, the cake is revealed to be a replica of the company building but tweaked in such a way as to remind those in attendance of the death they've all kept quiet. This launches Kōichi's plan to take vengeance on the people who destroyed his father's life.

"The Bad Sleep Well" is an impressive and unusual take on "Hamlet," as it pays homage to the source while following its unique narrative. The film offers a critique of corporate corruption while maximizing the lone hero subtext, making the plot genuinely relatable.

Ikiru (1952)

Akira Kurosawa's "Ikuru" is a loose adaptation of Leo Tolstoy's "The Death of Ivan Ilyich." The film is an examination of the value of life from the perspective of a man who knows his days are numbered. Kanju Watanabe worked the same droll bureaucratic job for decades, and as he approaches retirement, he's diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer. With less than a year to live, he reevaluates his life and its meaning, given how he lived and what he will leave behind.

At first, he tries to find joy and entertainment in Tokyo's nightlife, but he ultimately finds solace in a young woman retiring from his company. She helps him find joy in life, which he hasn't been able to do. He spends his last days working to have a playground built to support the local children. Towards the film's end, Watanabe dies, leaving his mourners to wonder about his complete change in character.

It's a solemn story that focuses on heavy themes of death, family, dedication to work, and the meaning of life. The film has a lasting legacy and has been remade multiple times, and bill Nighy leads the most recent adaptation, "Living."

Seven Samurai (1954)

Akira Kurosawa's "Seven Samurai" has been remade multiple times, with "The Magnificent Seven" and "A Bug's Life" standing as two of the most successful. Still, nothing beats the original, and "Seven Samurai" is easily Kurosawa's greatest film. The film is set during the late 16th century of the Sengoku period and is centered around a small village of farmers in Japan plagued by bandits. The villains come by periodically to steal the farmers' crops, leaving them with little to nothing for themselves.

Unable to stand up to the bandits, the farmers hire seven rōnin to wait and fight them once they return. While the rōnin are capable fighters, they cannot battle the bandits on their own. They train and arm the villagers after finding and burning down the bandit's camp. The film culminates in a massive ambush against the bandits, resulting in the death of the villains, leaving the rōnin to depart the victorious village.

"Seven Samurai" was the most expensive movie made in Japan at the time, and all that money and hard work paid off. The film is widely regarded as one of the greatest movies ever made and is arguably Kurosawa's best and most influential film.