What These Star Wars Movies Really Look Like Before Special Effects Are Added

When George Lucas came up with the idea of Star Wars in the mid-1970s, setting an adventure of this scope in outer space had never been done before. So how did he get the film to look so darn good when there were no visual effects companies up to the challenge at the time? He started his own.

Industrial Light and Magic was formed to handle the special effects in Star Wars, and they revolutionized the industry with their work. The original trilogy was lauded for what were considered mind-blowing visuals at the time, but ILM changed the game again with the Star Wars prequel trilogy, rendering landscapes populated with thousands of digital characters and pioneering the use of full motion capture. With the sequel trilogy off to a great start and a number of spinoffs in the pipeline, ILM are once again out to prove that they're the VFX industry's top dogs. Let's peer behind the scenes at what Star Wars movies look like before they work their magic.

Star Wars (1977)

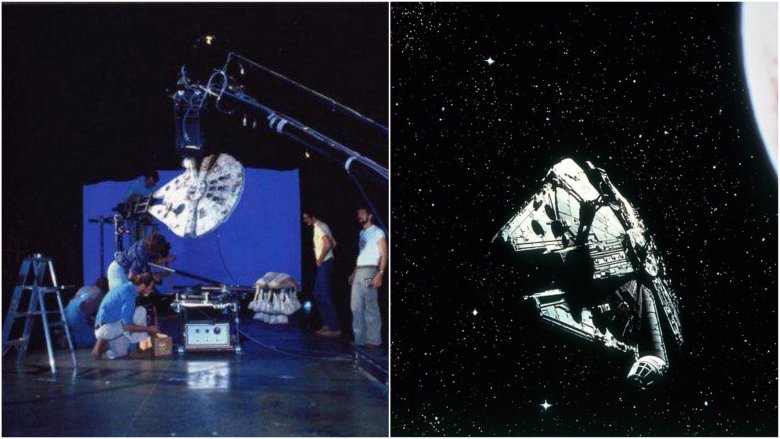

The original trilogy is known for its use of practical effects, but in truth those films relied on visual trickery just as much as their successors. Sprawling GCI backgrounds were not an option when the first Star Wars movie, 1977's A New Hope, was being made, so the effects artists at ILM came up with some ingenious alternatives. Matte glass paintings were painstakingly created by hand and then added to scenes later, though a painting can't move, which meant a different technique was needed to bring the movie's many spaceships to life.

"Back in the days of Star Wars, we kind of walked into an empty warehouse and sat on the floor and went, 'How are we going to do this?'" former ILM man John Dykstra told Den of Geek. "The producers, Gary Kurtz of Fox and George Lucas, took an incredible risk by listening to what myself and my collaborators had to say with regard to how to do this, because we were inventing this stuff from scratch." When it came to Han Solo's vessel the Millennium Falcon, Dykstra decided to create a model and film it in front of a blue screen using an early computer-controlled camera, which allowed his team to add the context of the scene in post.

The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

Dykstra won an Oscar for his revolutionary work on Star Wars, but the production was far from a smooth process, and Lucas chose not to bring him along when he moved his base of operations to San Francisco. It was here that ILM got to work on the next movie, but despite the success of the first film, budget restraints were still a problem when it came to making The Empire Strikes Back; as VFX supervisor Richard Edlund later pointed out, "Computer graphics were extremely expensive, very slow and the resolution was always a problem."

Luckily for Edlund and Lucas, the team they'd assembled proved more than capable of delivering results within their means. The film's cinematographer Mark Virgo compared this era in cinematic history to the lunar program in his '80s special effects tutorial video, referring to the period as an amazing cooperative of artists, imagination, optics, engineering, and home-brewed software. "I learned the blue screen process at ILM on The Empire Strikes Back," he said. "At the time, this process was considered cutting edge, the culmination of decades of photochemical tinkering."

Return of the Jedi (1983)

By the time 1983's Return of the Jedi went into production, the ILM crew had found their groove. Master of puppets Phil Tippet (who later revealed that he had a trippy experience with blue screens after taking LSD while working on the film) was brought in to head up the creature shop that ultimately created the Ewoks, and the rest of the effects work was divided between Richard Edlund, Ken Ralston and Dennis Muren. Among the jobs that fell to Muren was the speeder bike chase, one of the film's standout sequences—and one of the hardest to achieve, with 100 total effects shots.

"Because the bikes were going to be blue screen, the backgrounds didn't require that many different shots to do, because we could use them over and over again," Muren told StarWars.com. The VFX veteran explained that getting front and rear point-of-view shots from the bikes proved to be his biggest challenge. "I got the idea to do it with a Steadicam. I called Garrett Brown up, who invented it, and he flew out." Muller and Brown took the camera (the first of its kind to be genuinely handheld) to Samuel Taylor Park and got the shots. "We tried to mimic the bouncing in our blue screen shooting, and it had to be done a way that hadn't been done before."

The Phantom Menace (1999)

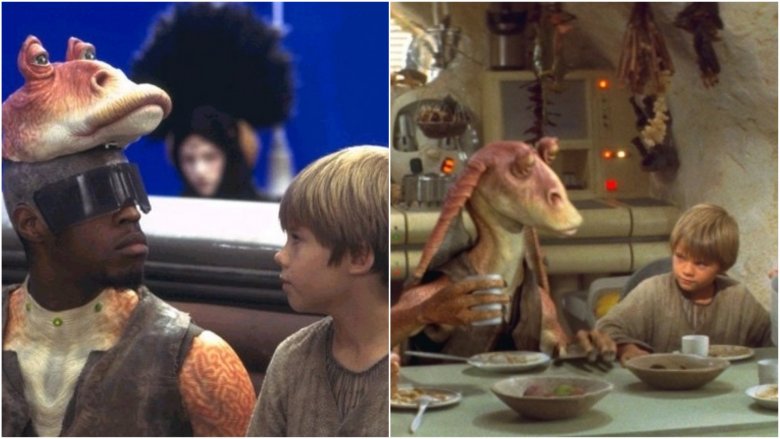

George Lucas' long-awaited return to the Star Wars universe with The Phantom Menace didn't fail financially (Episode I has actually made more than a billion dollars), but it let down a number of fans, who were quick to turn on new CGI character Jar Jar Binks. "Star Wars was my first 'most hated' title in anything really," Ahmed Best, the man who played the Gungan via motion capture, said. "It didn't put me off Star Wars, but yeah, it was painful."

Despite the overwhelmingly negative reaction to the character, Best is proud of the fact that he broke new ground with Jar Jar. "One of the biggest reasons I took it was because of the challenge of it, it hadn't been done before," he continued. "There was no Andy Serkis and Gollum, no Navi from Avatar... I was working with George to pioneer this new character form of acting and storytelling." Best (who also provided the character's voice) couldn't help but take the hate personally, but he's always had an ally in Lucas, who revealed that Jar Jar is the Star Wars character he'd most like to be.

The Phantom Menace

Unlike Best, the actor who played deadly Sith warrior Darth Maul only has fond memories of The Phantom Menace, his first experience on a movie set. "I wouldn't be where I am today if it wasn't for Darth Maul," martial artist and actor Ray Park told the Los Angeles Times. "It was the best feeling in the world to get to play this character." Park's primary fighting style is wushu, but he also practiced gymnastics and ballet in preparation for his big fight scene with Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor) and Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson), who proved difficult to work with because of his large frame. "Liam was so tall, and wushu has a low stance," Park said. "Liam would say, 'Hey Ray, can you just bring it up a little?'"

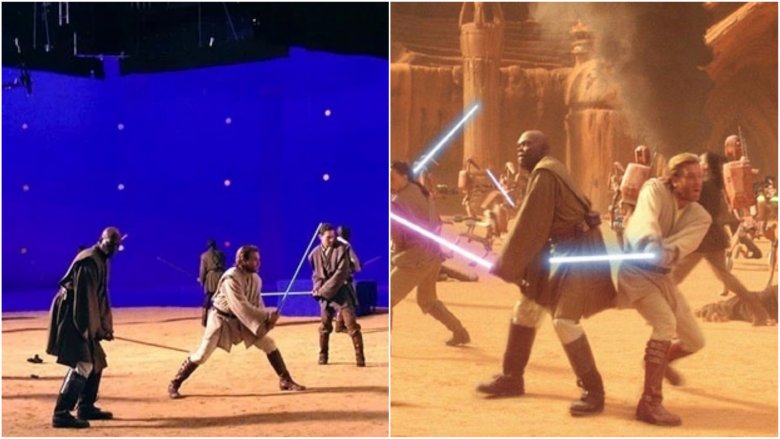

Once the choreography was worked out, the scene was filmed in front a custom-built blue set and handed off to ILM, just one of the many sequences they were required to complete. "It became pretty clear up front that this was going to be unlike any special effects movie ever done," producer Rick McCullum said. "George was thinking about somewhere between 1700 and 2000 shots, and the thing I was most afraid of was 'Can ILM do it? Can any effects house do that?'"

Attack of the Clones (2002)

ILM rose to the challenge laid down by McCullum, and while some of the CGI they turned out hasn't aged particularly well, what they managed was still a huge feat for the time. The advances in CGI meant that Lucas could set stories in parts of his galaxy that were previously inaccessible, which he took full advantage of. "That was the fun part of writing the project, I wasn't limited," he said. "Whatever my imagination could come up with I would just put down on the page and say, 'We'll worry about this later.'" He took the same approach when it came to writing Attack of the Clones, setting the bar even higher for ILM.

Animation director Rob Coleman was initially under the impression that some of the cityscapes and backgrounds Lucas required for Episode II were going to have some practical elements, but he soon learned this wasn't the case. "We were informed how little was actually going to be built on the stages in Sydney," he told AWN. "John [Knoll, ILM's Chief Creative Officer] and his group of people began to work on how we could improve our digital environments. John and his team worked for months trying to perfect that."

Attack of the Clones

Of the 2000 effects shots in Attack of the Clones, around half include completely computer-generated characters. A team of 60 animators worked alongside 340 ILM artists and technicians to render some well-known Star Wars faces in CGI, including a certain little green Jedi master. "The biggest technical challenge for me was animating Yoda," Rob Coleman said. "That was due to Frank Oz having created that character in The Empire Strikes Back as a puppet. This time, Yoda, who is supposed to be 2'll" tall and 874 years old, is much more active and prominent. He actually runs and has a lightsaber battle."

Yoda's duel with Count Dooku was one of the film's big visual effects set pieces, but it required some human input from Christopher Lee, who was one of the many cast members forced to work with blue screens for long periods of time. Ewan McGregor said he finds working with his fellow actors a rewarding experience, something CGI often robs you of. "You're doing lines against a blue curtain and it's really hard work," he said. "It's difficult to make that believable. I don't know if I have."

Revenge of the Sith (2005)

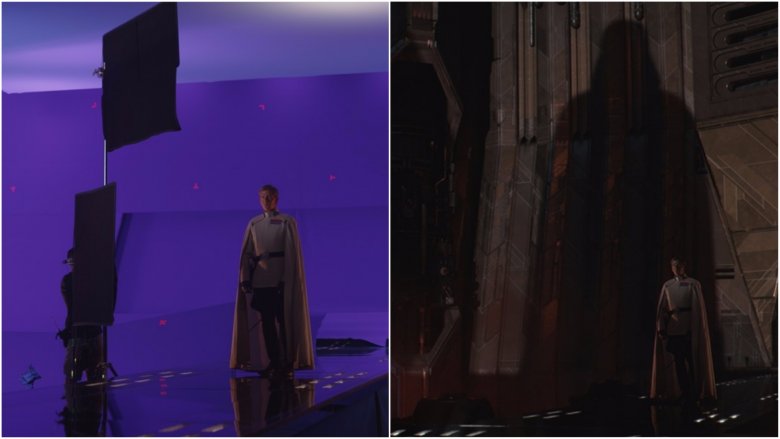

According to Ian McDiarmid (Sheev Palpatine), the use of green screen was really ramped up for the third and final film in Lucas' prequel trilogy, which had the most effects shots yet at 2,151. "I don't quite know how the digital process works, but I think I am right in saying that on Revenge of the Sith it was the first time the green screen technique was used to such an extent in a film," McDiarmid told The Telegraph. The British newspaper showed him a still photo from the set taken in 2003, and after some deciphering, he recognized it as the scene in which Obi-Wan and Anakin Skywalker (Hayden Christensen) rescue him from a kidnapping he orchestrated.

"So much of the filming took place in front of a green screen," he said. "I used to feel great sympathy for Ewan and Hayden because they had so much fighting to do and quite often had to fight imagined enemies, which is a little more difficult than just imagining that the pink dot on the floor represents something else. George often hadn't decided on details of the film, so Ewan and Hayden didn't know whether they were filming an ironic moment or whether they were about to die."

Revenge of the Sith

Episode III introduced us to General Grievous, the lightsaber-wielding Kaleesh cyborg who held the title of Supreme Commander of the Droid Army during the Clone Wars. Upon receiving the design for the character, animation director Rob Coleman knew ILM were going to have a tough job breathing life into this one. "Since his movement was so restricted, we decided to have him talk with his hands, because, although there is a grill pattern where his mouth would be, there are no articulating bits for his mouth," Coleman explained to AWN. "No lip-sync or facial expressions. No brow to move. No indication of what he is feeling or thinking."

Grievous wasn't the only villain without eyebrows in this movie. It's in Episode III that we get to see Anakin Skywalker become Darth Vader after he's badly burned in a battle with Obi-Wan. Hayden Christensen didn't realize what an honor playing the character was until he had the suit on. "It originally starts out as just this beige suit, which isn't very intimidating at all," he said. "But I still got this sensation of nostalgia that I wasn't aware I was going to feel. They could have just put some really tall guy in it ... I begged and pleaded and they were nice enough to build a Darth Vader suit that actually fit me."

The Force Awakens (2015)

Having worked with J.J. Abrams on his Star Trek reboot, visual effects supervisor Roger Guyett had "a tremendous respect for him as a director" going into The Force Awakens, and the pair's partnership proved as fruitful as ever. Episode VII made almost a billion dollars domestically and earned widespread critical praise, while Guyett and his team were nominated for an Academy Award for their work, much of which incorporated practical effects.

"From the beginning we knew we wanted BB-8 to be as practical as possible, so that the actors could interact with him, and of course J.J. could direct him on set," Guyett told Art of VFX. "The system that Neal [Scanlan] developed allowed BB-8 to be controlled by two puppeteers—one basically drove the broader motion with two mechanical arms whereas the second puppeteer was able to remotely control the head." Removing the puppeteers from shots later on proved tricky, but Guyett had nothing but praise for them. "Their acting defined his personality, that was the crucial element. We knew we'd end up with a lot of complex paint out of the puppeteers but having the droid 'live' was great for the overall performance."

The Force Awakens

Despite all the effort that went into making BB-8 real, there were still a number of scenes in which the character had to be rendered digitally out of necessity—around a third of all shots, in fact. "Some of the characters couldn't be done physically," Mike Seymour said in his Wired Episode VII breakdown. "On those occasions JJ was more than happy to push the digital technology [...] based on the performance of real actors, such as Lupita Nyong'o, who plays Maz." Nyong'o was looking for something a little different coming off the back of her Oscar-winning performance in 12 Years A Slave, and the part of pirate queen Maz Kanata seemed like the perfect challenge.

"Motion capture is something that I've had my eye on ever since seeing Andy Serkis in Lord of the Rings, and then going on to see Zoe Saldana do it, and Benedict Cumberbatch, and folks like that," she told Refinery29. "It looked like an opportunity to really play as an actor, because you're not limited by your physical circumstances. And after playing Patsey in 12 Years a Slave, which was so much about the body, here was an opportunity where I was completely relieved of that. And I liked it."

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016)

The first Star Wars spinoff impressed the majority of Rotten Tomatoes critics, who praised Gareth Edwards' film for breaking new ground in terms of both narrative and aesthetics. Among the major talking points was the digital resurrection of Peter Cushing (Grand Moff Tarkin), whose character was portrayed by Guy Henry via motion capture. "It's been bloody frightening, I can tell you," Henry said on a Rogue One DVD feature (via Radio Times). "It's very daunting, actually, to try and be a famous character in the original film. And also to emulate an actor that I myself admire."

VFX supervisor John Knoll was able to track down a cast of Cushing's face made for the 1984 movie Top Secret, which gave them a huge head start when it came to recreating the late actor's likeness. The process took a whopping 18 months to complete and was done with the permission of Cushing's estate, though there were some who felt that bringing actors back from the dead was wrong from an ethical standpoint. "This work was done with great affection and care," Knoll told Nightline in defense of the decision. "I'd like to think that the role that we gave Tarkin in this film is one that Peter Cushing would have been really very excited and happy to play."

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story

Of course, Tarkin wasn't the only bad guy making a return. Darth Vader was back, casting shadows and choking insubordinates just like he did in the original trilogy. One man who felt Vader's invisible grip after overstepping his mark was the villainous Orson Krennic (played by Ben Mendelsohn). As a childhood Star Wars fan, the part was a dream come true for Mendelsohn, who could barely contain himself during the scene in question, grabbing director Gareth Edwards and saying "Mate, look! It's Darth f***ing Vader!"

While seeing Vader dropping choke puns was great, the character's standout scene came right at the end—and it almost never happened. "That great Vader scene at the end, that wasn't what we originally shot," John Knoll (who also has writing and producer credits on Rogue One) told ScreenRant. "Vader stayed on the bridge of his Star Destroyer and devastated Raddus' ship and Leia's ship escaped. But, we were looking at the edit, and one of our editors had this idea of, 'Wouldn't it be better if Vader boards Raddus' ship and is fighting through Rebels trying to get to the plans before they escape and it's a much narrower call?' And as soon as we heard that, we felt it would be way better."

The Last Jedi (2017)

J.J. Abrams spoke at length about using as many practical effects as possible in The Force Awakens in order to recreate the feeling of the original trilogy, and his successor Rian Johnson adopted the same attitude when he took the reins for The Last Jedi. Neal Scanlan returned to head up the creature shop, who this time out were tasked with creating a new breed of animal called a vulptex, a fox-like inhabitant of the salt-covered planet Crait. "The idea is that these wonderful sort of feral creatures had lived on this planet and had consumed the planet's surface, and as such had become crystalline," Scanlan told Entertainment Weekly.

To get an idea of how such a creature might move, they fitted a fox-sized dog with a suit adorned with translucent drinking straws. "It was amazing to see him run around," Scanlan said of their four-legged volunteer. "It could run and jump, and it had this wonderful sort of movement to it. It had a great sound to it, as well, because all the little straws moved and flexed with the animal." The next step was creating an animatronic puppet that the cast could interact with in scenes, but much like the BB-8 build, it wasn't possible to use it 100 percent of the time. Static models complete with 25,000 individual crystals were built for the benefit of the VFX team, who were able to scan them and render the vulptices however Johnson wanted.