That's What's Up: Why Archie Is The Most Versatile Character In Comics

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: What makes Archie and the gang so versatile? Horror, Teen Murder Drama, countless crossovers, they seem to suit any genre. —@MattLune

Being a comic book fan these days is weird. People are suddenly really happy if you compare them to Aquaman, there's a major motion picture raking in millions of dollars that features a cameo appearance by the Bi-Beast, there's been a crossover about the DC Multiverse on television two years in a row. It is wild—and for a lot of people, the wildest thing of all might just be that there's a hit television show where the Archie characters have to deal with meth dealers, serial killers, accidental incest, and street gangs, without ever getting to the point where they're not recognizably the same characters from the comics you can buy at the grocery store.

Really, though, that makes a lot of sense. Don't get me wrong, a good bit of the fun of that show is that it's well aware of the power of shock value, and how hilarious it is to watch hapless klutz Archie Andrews forming a vigilante gang of shirtless teens, or see Jughead installed as a crime lord. But the fact that it works? That's not shocking at all. It's just the natural end result of a company spending decades making sure their characters could work in any kind of story.

The secret origin of Archie Andrews

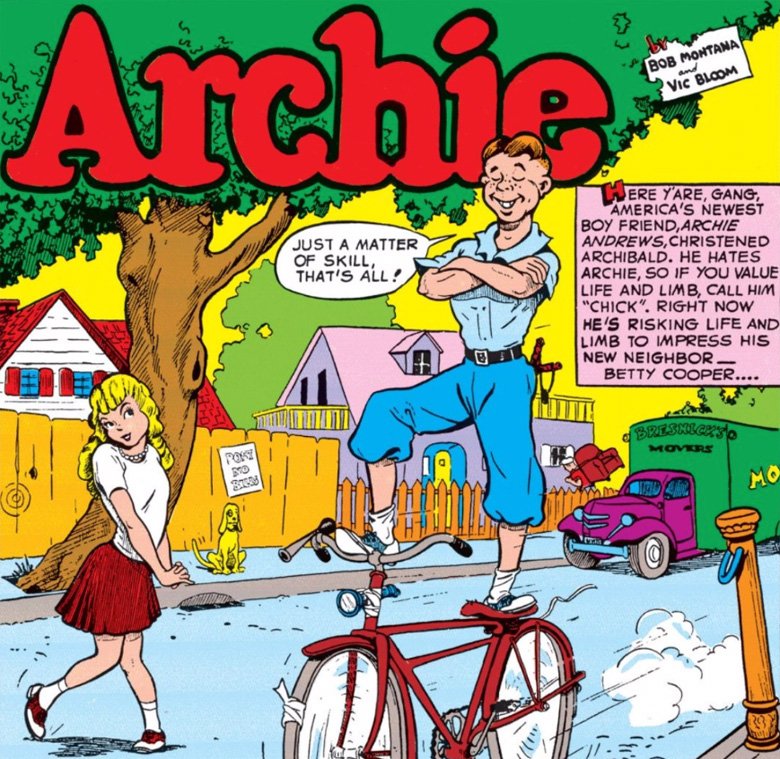

Of course, he didn't start out that way. When he was introduced by Bob Montana and Vic Bloom in 1941, Archie Andrews wasn't really the character that we know today. In fact, he wasn't even "Archie." Despite using his given name for the title of their new strip, Bloom and Montana's version of the character hated his given name, and preferred to go by "Chick," which, in retrospect, is not actually that much better than "Archibald." That's probably why it didn't stick around for long, although it did wind up being re-used as the first name of Betty's secret agent brother, Chic Cooper. But we'll get back to him in a second.

Aside from the hair, "Chick" is barely recognizable as the same character. Rather than being Riverdale's resident capital-letter Solid Dude, he's more of a Daffy Duck type: a hotheaded daredevil who brags his way into trouble and gets a slapstick comeuppance for biting off more than he can chew. Even that makes sense, though—Archie can only really be the character he'd become once everything is in place around him, and in those early stories, the other pieces just aren't there.

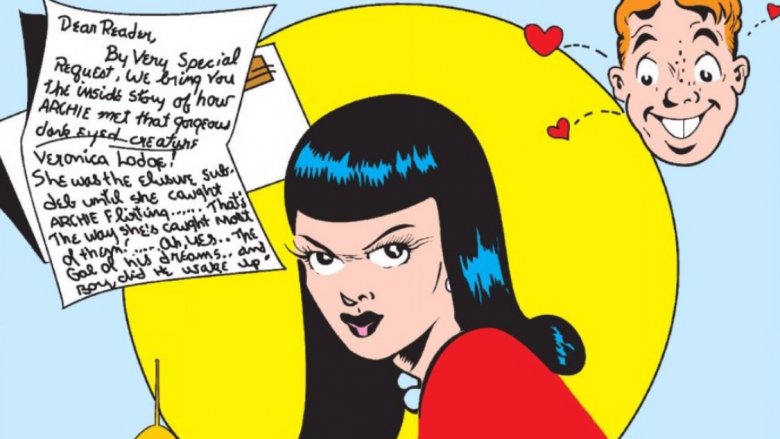

Betty's there from the start as the lovestruck neighbor, and Jughead appears in that first story as the same sleepy-eyed, romance-hating pal he'd be for the next few years. Reggie, however—a character who would wind up having more in common with "Chick" than the Archie we know, and would fittingly wind up frequently playing the Daffy Duck to Archie and Jughead's Bugs Bunny—wouldn't show up until the next year. More importantly, though, the single most important element of Archie comics wouldn't arrive until April of 1942, when it swept into town with one Veronica Lodge.

The greatest love triangle in comics

In the same way that those first six months of Batman stories don't really feel like Batman because they haven't figured out his origin, Archie stories weren't really Archie stories until Veronica showed up to complete a love triangle so prominent that it became a pop culture icon.

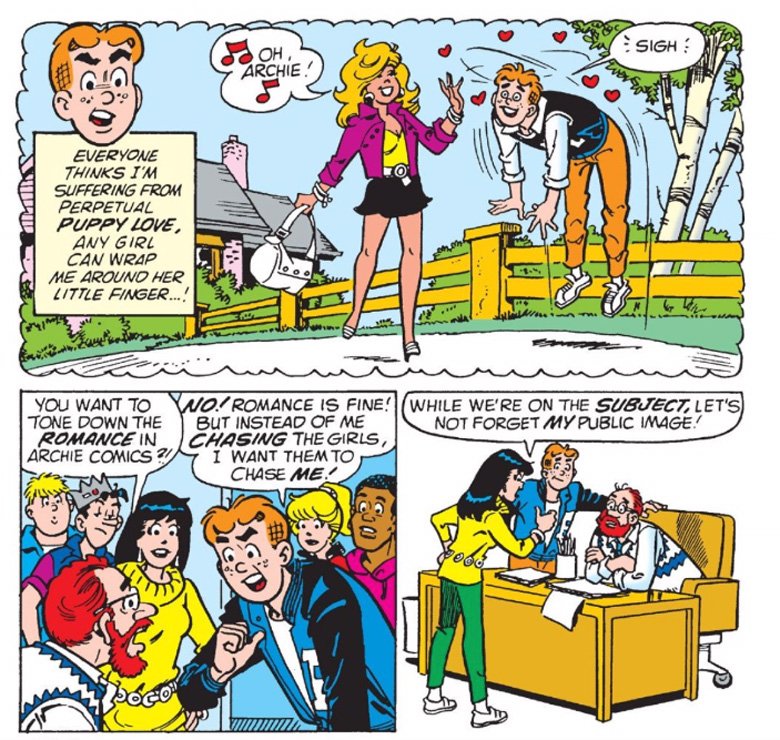

The change is darn near instant, too. The first Veronica story—where she's a beautiful "sub-debutante" lured from New York to Riverdale because she thinks it'll be hilarious to go on a date with some "farmer boy"—is also the first story where Archie tries to juggle two dates at the same time, and ropes Jughead into a complicated scheme of keeping Betty and Veronica from finding out about each other. It's the classic Archie setup, one that would be repeated over and over again throughout the years, and it makes it clear that while Archie finding himself in over his head is good, it's a whole lot better when Betty and Veronica are involved. With that in place, it became apparent that the love triangle was not just the most important thing in Archie Comics, it was the only thing that mattered.

As long as that's there at the core of the stories, you can do pretty much anything else and make it work. That's when the characters started being redefined not by personality traits, but by relationships. Archie became girl-crazy but otherwise honest, kind, and likeable because the stories had to justify not just why he'd be juggling two girlfriends, but why they'd be so into him that they wouldn't offer up an ultimatum. Veronica and Betty themselves became defined in opposition to each other—one rich, the other poor, one fickle and unimpressed, the other utterly smitten and devoted.

Everything's Archie (or at least Archie-adjacent)

It even shapes the characters around them. Reggie becomes the rival who's sinister and scheming, as opposed to Archie, who's naturally good-hearted and therefore truly terrible at deception. Cheryl Blossom shows up to be a wrecking ball that smashes the existing love triangle once it gets too predictable—and in the process, went so far that she was legendarily banned from the comics page for a few years for being too sexual.

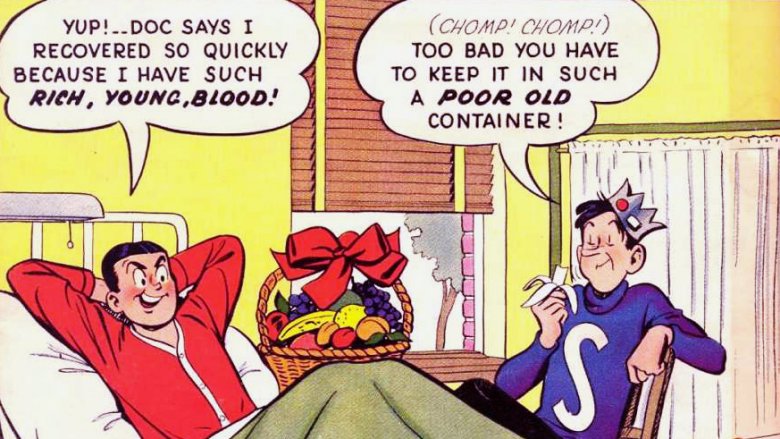

The best, of course, is your boy Jughead Jones. From his very first panel, he's described as a "girl hater"—something that led to decades of subtext where he was read as gay before being canonically revealed as asexual a few years ago—and he becomes the only person in a universe defined by a love triangle who is completely immune to romance, and therefore able to act on the plots and schemes in Riverdale without ever actually being a part of them. That simple definition, a character who is in a world, but not of that world, gives Jughead a metatextual quality that makes him one of the best characters in the history of comics, right up there with Scrooge McDuck and Jimmy Olsen.

No, really. But that's something we can get into another time.

Filing down the edges

The point of all this is that the love triangle was so strong, so central to the characters, that everything that wasn't strictly necessary for it just sort of fell away. As Archie's popularity held strong throughout the decades—thanks at least in part to the publisher being one of the primary motivators behind the Comics Code Authority, which helped to thin out the competition—it became necessary to find ways to fit him into different kinds of stories. As long as that core idea of the love triangle remained in place, you could pretty much just do anything you wanted. Which they did.

Aside from one or two defining traits—in Archie's case, "girl-crazy" and "klutzy"—the characters had everything distinct about them filed off, or at least shifted over to their more generic forms. Veronica, for example, was rich because her father was a Businessman, and the limits to her wealth and Hiram Lodge's particular industry were, well, whatever the story required them to be. She was richer than Reggie, but not quite as rich as Cheryl Blossom, and Lodge Industries was vague enough that her family could be investing in real estate or debuting a new high-tech car, depending on what the creators thought would make for the best gag that week.

As you might expect from the fact that his name's on the cover, Archie himself was the one who got filed down the most. When it came to sports, for example, he wasn't a football player or a baseball player, he played Sports, as in, the concept. That meant they could do different kinds of stories depending on when each one would be published, with a new round of baseball stories every summer and a couple about the football team every fall.

Top of the Pops

The only thing that really stuck around as a permanent change was Archie's desire to be a musician, which had less to do with character development and more to a weird stroke of fate that saw "Sugar Sugar" becoming the real-life #1 single of the year 1969, despite being recorded by a fictional band.

Even that, however, was the product of making the Archies more and more generic. They formed a band because forming a band was something kids in the '60s did, and they were a five-piece ensemble because there were five characters to find roles for. Seriously, the fact that there's actually a keyboard in this song for Ronnie to play, as difficult as it might be to make out, is just a very pleasant coincidence.

Beyond that, though, Archie had been stripped down until he was barely two-dimensional—and I don't actually mean that in a bad way. There's definitely a downside, of course. Since he became the the character that everyone else was defined around, Archie became the baseline, meaning that the character at the center of an entire comic book universe was actually the least interesting thing about it. But the upside to all this is that at the end of the day, Riverdale's favorite teens weren't really characters at all.

They were archetypes.

Archie-types?

And the thing about archetypes is that by definition they can work in any kind of story. They're defined by their situations, with the genre and environment around them determining how their defining traits are emphasized. In the mainline Archie stories, it was a wacky romance, with everyone's traits taken to their most comedic extremes. But it wasn't long before the folks over at Archie (the company) realized they could get a lot of mileage out of dropping that same set of archetypes into different kinds of stories, keeping all those character relationships the same and just changing around the environment in which they were meant to play out. And that's when things started to get weird.

But here's the thing: Archie's always been weird. For the casual readers who only really know Archie as the kid-friendly comic that you can still buy in the checkout line at the grocery store, I have to imagine that stuff like Riverdale or Archie vs. Sharknado—which really exists—are probably pretty surprising. If you actually go back and dig into the history of those comics, though, it's really just an extension of what they've been doing all along. The only real difference is that this time, people noticed.

Archie gets weird

If you really want to put a pin into the moment that led directly to where we are now, with a sex-charged, murder-filled soap opera on television alongside a rebooted Archie comic directed at young adult readers, the best choice is with the debut of Afterlife With Archie. The shift in the company's strategy had happened a little earlier with major changes like the introduction of Kevin Keller, well-publicized stunts like the Archie Meets Glee crossover, and the truly bizarre Life With Archie series.

That one, if you missed it, was an extension of the big anniversary stunt where Archie finally got married, which of course was spread over a handful of different possible futures. He wound up marrying Betty, Veronica, and Valerie from the Pussycats (in divergent timelines, not at the same time), and then died when he took a bullet to prevent Kevin from being assassinated.

In retrospect, though, all of those feel like a prelude to Afterlife With Archie. What started as a joke riffing on Life With Archie's title quickly became one of the best books they'd published in years, focusing on the idea of a zombie apocalypse hitting Riverdale, fueled by Jughead's endless hunger. That was the series that opened up the floodgates for seeing Archie dropped into new and specifically more violent genres—and it's not a coincidence that Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, who writes Afterlife alongside artist Francesco Francavilla, would become the company's Chief Creative Officer and the head writer and showrunner of Riverdale.

The razor-thin, blood-soaked line between horror and comedy

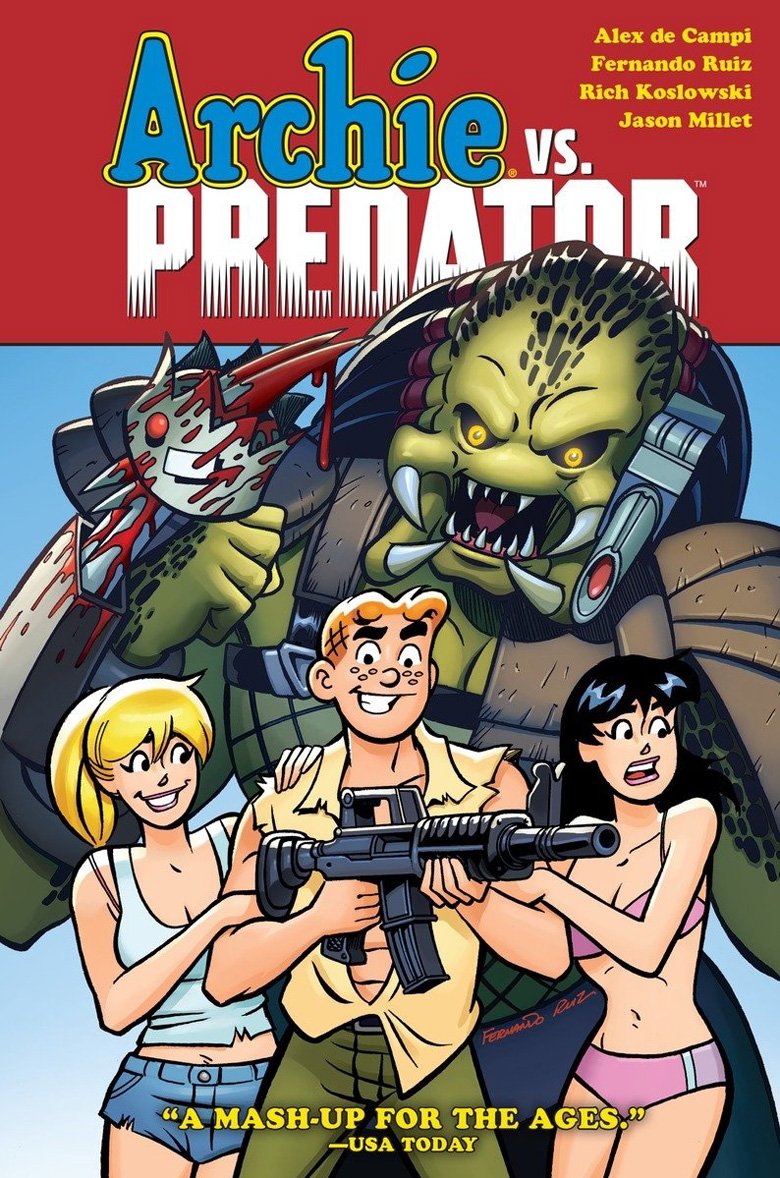

Afterlife wasn't the only story to take that approach, either. Not long after it debuted (and not long after Archie found some pretty marketable success with a ton of crossovers, including Archie Meets KISS), Alex de Campi and Fernando Ruiz teamed up for Archie vs. Predator. As in the monster from the movie Predator. And it rules.

Both of those books work for the same reasons. For one, they play off the expectations that we have from 70 years of seeing these character in a specific kind of hashtag-relatable teen comedy. But from a genre standpoint, it works because comedy and horror are so closely related that the archetypes that you find in one are the same archetypes you find in the other. Afterlife is straight-up horror, and AvP certainly leans into the comedy inherent in having a horny teenage Predator show up to murder most of Riverdale in an effort to impress Betty and Veronica, but the characters remain consistent because they're always operating on the same set of principles.

Horror, comedy, and thrillers like Riverdale are all built around building and breaking tension. The only real difference comes from the way that tension breaks, and how the consequences are treated in the story. In a comedy, Archie trying to keep secrets from Betty and Veronica—like, say, the fact that he chose to ask both of them on a date on the same night—can lead to wacky hijinx. In a horror story or a thriller, it's just as likely to wind up with someone dead. In both cases, the audience is bringing in a set of expectations that lets us see those consequences coming a mile away, and it's when those expectations are subverted that the stories are at their most effective.

It's definitely more prominent now than it's ever been before, especially with the mainline Archie comic doing stories with plot points like Betty being paralyzed in a car accident, but it's not a new idea. Archie's been doing that stuff for years.

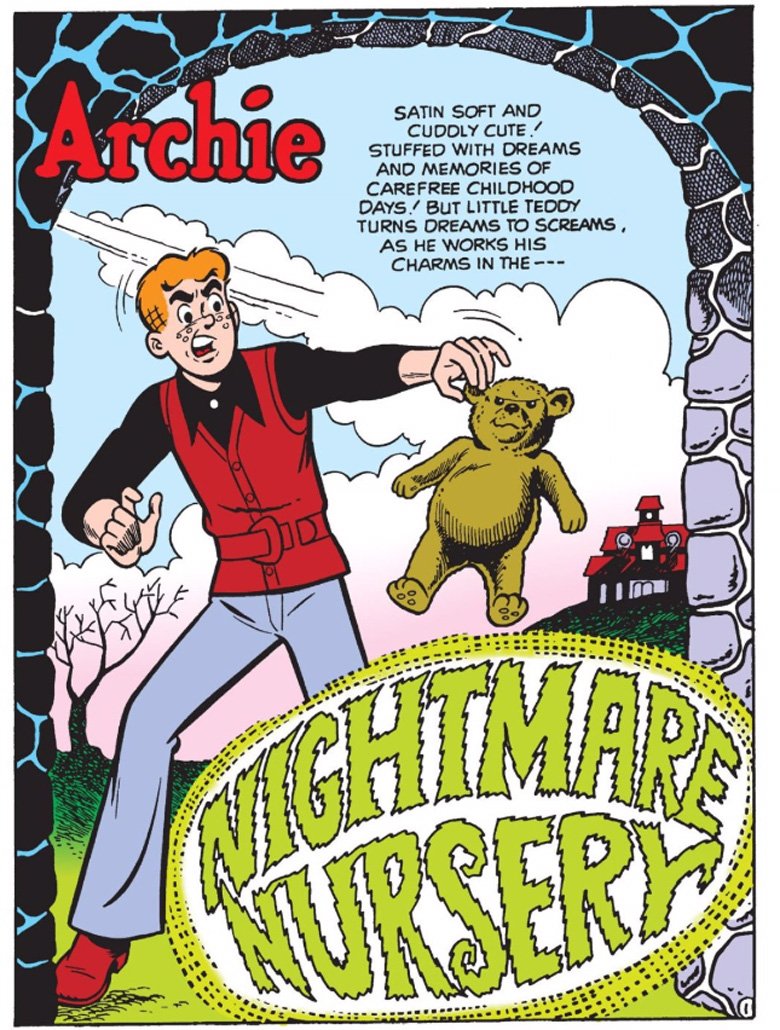

This stuff happens all the time

Throughout the history of Archie comics, they've dropped that dude into as many different genres as you care to name, from superheroes to spy stories to a multi-part epic where Veronica discovered she was "The Ender," a prophesized heroine who was destined to slay all vampires. For the most part, those stories are done as comedy and genre parodies, with the gang forming an ensemble cast that can be switched into any kind of story for a few laughs, but there are plenty that actually make an attempt to do those stories for real.

There were multiple titles in the '70s, most notably the original Life With Archie, that were devoted to serious stories about Veronica being kidnapped at knifepoint, or Betty nearly being mauled by a bear while she's out on a nature hike. Those stories are almost completely forgotten today and were very rarely reprinted—which, of course, makes them some of my favorite bits of comic book weirdness—but they provided the proof-of-concept blueprint that showed how adaptable those archetype characters could be.

Admittedly, they weren't always good...

Stay high rez, cowboy!

... but I think it stands to reason that we wouldn't have stuff like Riverdale without them. Now if only that show would quit messing around and introduce Jughead's Time Police already. Cole Sprouse in his weird little hat defending the space-time continuum is exactly what we need in these trying times.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."